The last public “scoping hearing” on the proposed Millennium coal export terminal is tomorrow in Tacoma. But there’s a fascinating story that’s unfolded as these hearings have progressed: the companies promoting the Millennium project have found themselves in increasingly dire financial straits.

Let’s start with Arch Coal, which owns 38 percent of the Millennium project. Just last week, Moody’s, a bond rating agency, downgraded Arch’s debt—a move that is likely to increase Arch’s borrowing costs. Here’s what Moody said about the downgrade:

The rating action was prompted by recent deterioration in performance due to continuing weakness in the coal industry, and our expectation that…the potential for material recovery in demand and pricing is limited.

And yesterday, Morgan Stanley piled on, downgrading Arch stock on concerns about the domestic coal market. The move prompted a sell-off in which Arch lost between 5 and 6 percent of its market capitalization.

As tough as things are for Arch, Ambre Energy—the owner of the remaining 62 percent of Millennium—has it much, much worse. I reported yesterday that Ambre has filed its financial statements in Australia, but hasn’t made the document available on its website. Well, surprise, surprise: a faxed copy of Ambre’s financial statement landed in my inbox last night.

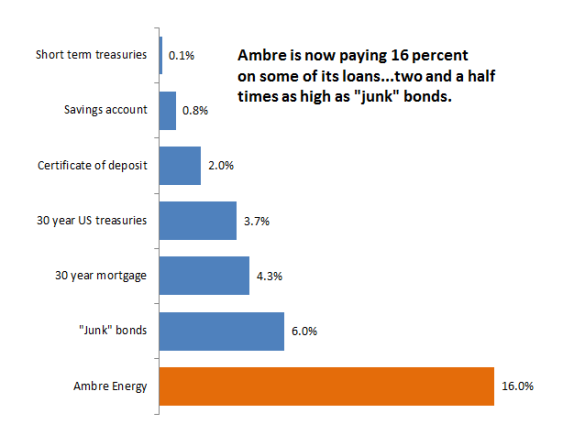

The following chart summarizes the news for Ambre: the company is now paying 16 percent interest on some of its loans. Sixteen percent. That’s over two and a half times worse than “junk” bonds.

That’s right: for a two-year loan, two Korean utilities are now charging Ambre an interest rate of 16 percent. That’s a rate that makes high-yield “junk” bonds look like sober blue-chip investments. And the only reason I can think that Ambre faces such high borrowing costs is that nobody will loan Ambre money at a lower rate: the capital markets think that Ambre is just too close to defaulting on its loans, and demand a premium that’s commensurate with the risk.

And if that weren’t bad enough, Ambre’s 2012 year-end financial statement also revealed that:

- Ambre lost about $30 million in the six months since its prior financial statement (see p. 11), and has lost about $153 million since the company’s inception (p. 22).

- Ambre’s average monthly losses on US operations were even higher from July through December 2012 than for the previous year.

- Both of Ambre’s co-owned mines lost money. In the prior reporting period, only Decker lost money; in the last half of 2012 Black Butte posted a loss as well (see p. 47).

- Ambre is hoping to spin off its money-losing “alternative fuels” division (pp. 11, 42, 43, 76), which has been trying unsuccessfully since 2006 to turn low-grade coal and/or oil shale into liquid fuel.

- Ambre’s main backer, a Denver-based hedge fund called Resource Capital Funds, appears to be trying to wrest control of the company from current management. As I read it, RCF is threatening to withdraw all financing, and essentially blow up the company, unless existing shareholders give RCF majority voting power (p. 53).

This is all based on a quick read of the financial statement: it’s possible that there’s even more dirt to be found. I suspect that news like this is why Ambre has been so reluctant to release their year-end financials: they suggest that the companies pursing coal exports are growing desperate, and capital markets are increasingly unwilling to put money into ventures with such a high risk of failure.

Donald T. Coughlin

Dear fellow CO2 users & abusers:

I lost half of the little retirement I owned in the market crash of 2008. We are cheated with externalities from non-renewable energy investment progressions. I protest within Olympia, WA and am a member of three environmental community groups. Coal failures like this in the article are a sign of our win! We must stop Coal Trains, stop fracking, and stop tar sands. Our children have one world. First and foremost, we are peaceful and we are smart protesters. Conjoin & congeal, learn how to protest, and share a bit of cash to another arrested protester when in need.

Clark Williams-Derry article is explaining a beginning failure within the petroleum industry. We are to watch the domino failure with empowerment. CO2 for our children or we conjoin and congeal for a long-term peaceful fight!

I am seeking a website to send a $20 to the brave Native American New Brunswick 40. I would like to see peace for their social circle as a futurity of familial culture and brotherhood. But, today we must conjoin & congeal for a fight! Fight smart, fight for peace, fight with disruption. Fight as Geo. Washington and a hatchet.

Don

Tom

Page 47, note 1, subsection (z) states “The Board acknowledges that without further funding the group will deplete its cash reserves within 12 months of the date of this report.”

Looking at the financial statements, they are burning cash at a high rate. The way I read the rest of subsection (z) is that without additional funding, they will likely be bankrupt by within 12 months.

Tom

Additional note: Page 47 of the pdf is labeld page 41.