The Oregonian ran an interesting piece in today’s paper, pointing out that total miles driven in the state peaked nearly a decade ago.

When the economy took a nosedive in 2008, dragging jobs and disposable income with it, Oregon residents reacted by driving their cars less. Or so goes the conventional wisdom.

But an analysis of new traffic data by The Oregonian shows that driving in the state actually peaked in 2004, four years before the Great Recession hit. What’s more, for the first time in the history of America’s love affair with the automobile, the driving levels nationally aren’t tracking economic growth.

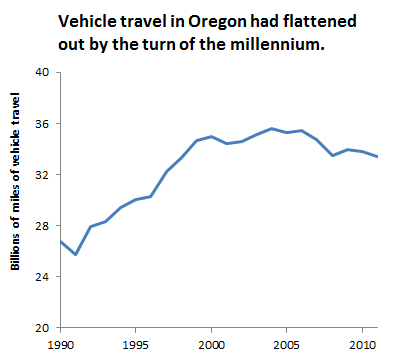

This is absolutely right. But the backstory is perhaps even stranger: driving in the state effectively stopped growing as far back as 1999 or 2000. Starting around then, vehicle travel in the state reached a bumpy plateau…with a few ups and downs, but nothing like the growth the state had experienced in prior decades.

Here’s a chart that makes the point:

The numbers come from the federal Highway Performance Monitoring System. They show a nominal peak in 2004, as The Oregonian noted. But they also suggest that traffic flattened out sometime around 1999 or 2000. Knowing what I know about the data gathering methods—which rely on one-time annual samples for many stretches of road, and statistical guesses for many other roads—I expect some statistical noise in the traffic counts. So the pattern to me looks less like a 2004 peak than a flat line starting in about 1999, with maybe a bit of decline since the recession.

That said, I’d say that the trends on state-owned roads, where traffic is monitored more closely and accurately than county and city roads, more clearly suggest a trajectory of peak and modest decline:

Regardless of these nuances, I think The Oregonian is definitely on to something: vehicle travel in the state stopped growing roughly a decade ago. There’s no doubt about the data. But the story is completely at odds with the common belief that traffic grew steadily until the 2008 recession, and after briefly falling, has now resumed its steady increase.

The reasons for peak driving are complex—a mix of economics, evolving technologies, shifting demographics, and cultural changes. But the implications are clear: transportation policymakers will have to wrestle with a new reality of declining gas tax revenues and no net growth in demand for new road space.

TOM

Can’t believe there are no comments here, the source article has 400. My comment won’t be lost among the many.

The plateauing of VMT in OR is greater than the national trend and bears examination.

My own take on it is that the cumulative costs of VMT have risen greatly when matched to employment and disposable income. Not only has fuel cost gone up but so have all other auto-related costs while income that could be applied to these new costs has stagnated or significantly dropped. There is a real change not to the American lifestyle but to our standard of living. While costs remain high over time this will not change, but if the supply of money, or credit, increases then demand will increase. The projection just might reverse itself. Also, the VMT total is not in a nosedive. The numbers trips driving all modes of transportation may drop but the need to travel has a threshold maintained by both the population size(and growth) and the economy(in jobless recovery). The authors of VMT regression reports all concede a new peak is possible. In the meantime we should also hedge our bets for the future.

Clark Williams-Derry

Agreed completely. A large part of the trend we’re seeing here is economic: stagnating wages for lower-income folks, higher fixed and marginal costs for driving, etc. More generally, the price of driving a private car is going up compared with alternatives — e.g., using transit for some trips, substituting some car trips with virtual “trips”, ride sharing, using transit. The utility of some of these modes has gone up with technology: transit use is still growing, in part because of economics, in part because mobile phones have reduced the transaction costs of scheduling a transit trip, in part because mobile devices have given more people something to do on the bus…

And then there’s demographics.

But I certainly don’t subscribe to the idea that VMT have necessarily peaked. They may have, but it’s too early to tell. Lots of other factors and forces, from fuel prices to technology trends to cultural shifts, will affect future demand in ways that are impossible to predict.