A week ago, I took my youngest son Peter, who is 19, on a cross-country trip. He was leaving the nest to start college in Ohio. We decided we would take the week, just the two of us, and go east across this magnificent continent together. We would mark his transition to the next phase of life with a physical journey of epic scale. It was a proud and bittersweet time for me, as for any father, and it brought us closer.

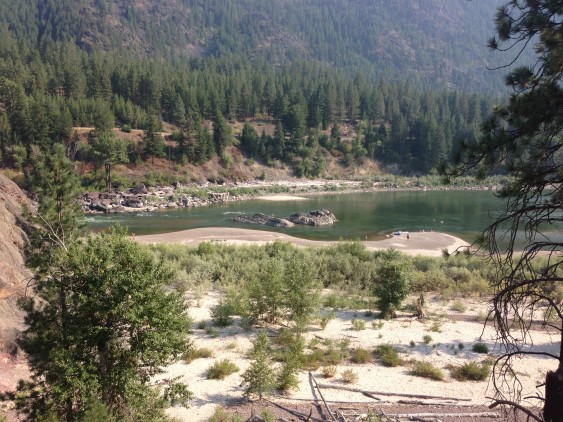

We stopped to rest at a swimming hole in the Clark Fork River, near Superior, Montana. While we were there, a coal train rumbled westward on the railroad right-of-way visible across the river in the picture below.

We walked by the water. Peter found some of the best skipping stones I’d ever seen. He threw a few.

The Clark Fork, like so many of Cascadia’s rivers, is an enchanting place. Here’s what it looks like right now.

Clark Fork River train derailment, courtesy of Jane Brockway

Early this morning, a 66-car freight train derailed in a canyon close to our swimming hole. Twenty-three cars came off the tracks. Four ended up in the river. Two of them are tanker cars. Fortunately, they’re currently empty.

Accidents happen. Ships crash into piers. Trains derail. Sometimes, they blow up. A similar derailment happened nearby in 2009.

Fortunately, the train was mostly carrying wood products. Some lumber spilled and some wood chips. Thankfully, no fossil fuels—no oil, no coal, no petcoke, no tar sands crude—pollutes the Clark Fork today.

But it’s the same route that some energy companies propose to bring tens of millions of tons of coal across each year, plus hundreds of thousands of barrels of oil.

Accidents happen. In a globe-spanning industrial economy, some of them are sure to be big. If King Coal and Big Oil have their way, it’s only a matter of time before a derailment contaminates miles of the Clark Fork.

But that doesn’t have to come to pass. We don’t have to turn the Clark Fork into an export corridor for dirty fuels. It’s a lousy idea in so, so many ways. It’s not the future we northwesterners have been trying so hard to build for our place—a future worthy of our children and the journeys they have yet to take.

Matt McRae

Thank you for the report, Alan. Somehow I hadn’t heard about the derailment…and upon a little searching, find out that’s not the first time this rail on this river has proven faulty… http://www.epa.gov/osweroe1/docs/oil/fss/fss04/nakad_04.pdf

..a 1999 spill put somewhere over 7500 gallons of asphalt and a few other delights directly into the river…. Crikey.

Cherie Garcelon

We live across from the railroad tracks in Arlee, MT. We used to have just intermittent rail traffic, now we have all of the trains with the empty coal cars coming by. The longest I counted was 121 cars not counting the engines. Luckily, at this time the full trains don’t come through our town, I think it has something to do with the passes on the way, but we do get the empty ones day and night. Breaks my heart to think of all of that coal going west to be burned and add to our climate problems.

Charmaine Slaven

I grew up around the Clark Fork river, swimming, fishing, boating… I’m so glad this particular derailment didn’t contain petroleum products, but scary to think of what could happen if it did!