This post originally appeared in the Daily Journal of Commerce’s blog SeattleScape.

This post originally appeared in the Daily Journal of Commerce’s blog SeattleScape.

Let’s say you’re the mayor of a medium-sized city in Washington state —let’s call it Northlakeshoreline —and your city has a problem. The country’s economy is a mess, of course, and the closing of a large factory in your city hasn’t helped things locally. You’d like to be able to make some significant improvements in a part of your city that is really run down. But your budget is tapped out dealing with bigger demands on social services and just keeping up with basic city needs.

You have an idea. Why not draw a line around the part of the city— let’s call it the Sherwood Forest neighborhood—that has some of the lowest property values and the biggest problems with roads, drainage, and basic infrastructure needs. You ask the assessor to give you a snapshot of how much all that property is worth and you partner with a local developer who gives you a sense of how the value of the property could be increased. After a lot of discussions, meetings, and number crunching you realize that if you fixed the infrastructure problems you could attract new development that would significantly improve tax revenue from Sherwood Forest—enough revenue, in fact, to pay for the improvements. But that revenue is off in the future. What do you do?

You call in your finance expert who suggests that you sell bonds—basically borrow the money for the improvements—then, as the property values go up from the new development, you can use the increased value from the properties in Sherwood Forest to pay back the loans over time.

What a great solution, you think. Borrow money now to fix up a neighborhood, create some jobs and economic activity in the process, and pay back the loan with the increased taxes you can collect. You’ve just invented Tax Increment Financing (TIF).

Tax increment financing is one example of something called value capture. It’s the idea that a good with future benefits that is out of reach today can be paid for with loans, and those loans can be paid back with the benefits of the good created with those loans. The increase in property values in the Sherwood Forest TIF district pay for the annual loan payments. This means as mayor you don’t have to make any cuts in order to pay for the improvements. And the best part is that after the loan gets paid off, the city can keep the extra tax revenue for use in the general fund. Tax Increment Financing has been used most notably in Oregon where the Pearl District in Portland is often cited as a big TIF success story.

Of course, in the real world, the implementation of TIF is far more complicated. But the concept is pretty straightforward. Cities and counties in Washington State don’t have access to this tool. Why not?

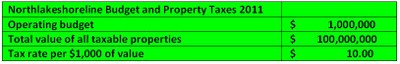

Washington State doesn’t collect taxes using a rate based system. Believe it or not, part of what makes the story I just told work is that there is a fixed rate of taxes assessed on the property from year to year. Attaching a rate—x percent of tax of the total value of a property—is important because as the value increases incrementally, a city can capture that incremental increase and pay off the debt.

Washington has what is called a budget based system of collecting taxes to fund the operation of government. That means that our fictional city of Northlakeshoreline would come up with its budget first, then levy a tax on all the properties so that they share the burden equally. That means the tax assessment is evenly distributed over all the taxable properties in the city.

Under Washington’s constitution a city is able to borrow money to improve public infrastructure and those improvement might result in increased property values. But the taxes that the city collects on those properties are NOT based on their assessed value. Those properties are taxed based on a rate set by the value of new construction throughout the city, the previous year’s city budget, and up to an additional one percent of the previous year’s city budget. That rate is applied, equally per $1000 of value, to ALL properties across the city.

Confused? Join the club. This budget-based problem is what makes TIF in Washington such a challenge. The framers of the Washington State constitution were aiming to create a fair and predictable system for assessing property taxes. They wanted to be sure that some people wouldn’t be unfairly targeted for extra taxes. Taxing all property uniformly—essentially a flat tax—seemed to them the best way to create a fair system. But it also creates other problems.

One problem is figuring out how to capture tax revenue to provide services that benefit just one part of a tax district. If I have a mosquito infestation near the river, why should the people who live across town have to pay to fix that problem? But I can’t tax the folks by the river more than the others because of uniformity. That means I have to pay to fix the problem out of the general fund that everyone pays into, in order to fix a highly localized problem.

But the framers, in their wisdom or by accident, allowed for the creation of taxing districts. So the city of Northlakeshoreline can create a Mosquito Control District (yes they exist!) so that people who live by the river can get taxed—uniformly—to attack the mosquito problem. So they will pay more property tax per $1,000 of value of property, but they also get the benefit of the services their taxes are paying for. A TIF district wouldn’t be providing services but infrastructure—roads, drainage, and parks for example—and paying for them over time. It is possible that the TIF challenge will be met by creating a new kind of taxing district.

And the other option might be to just amend Washington’s constitution to exempt properties in designated TIF areas like Sherwood Forest. There ARE already exemptions (in sections 10 and 11 of Article VII of the constitution) that tax property owned by senior citizens and certain kinds of farm and timber land, and open space at a different rate than other properties in a taxing district. A similar carve out could be made for properties in TIF areas so that they could be taxed with a rate that would allow the capture of additional value.

No matter what, the time is now for TIF. But the next part of the story will be whether the openings left by the framers for creating new districts are wide enough or whether a constitutional amendment is needed.

Photo of the North Pearl District by the author.

Jonathan

So as it is now, the government spends money on projects which are directly in the public interest.As I understand the TIF suggestion, government should borrow money and spend it on projects which would not traditionally qualify as benefiting the public as a whole. But that’s OK, they say, government gets the project for free because future taxes will be higher, funding the debt service.It seems to me that this creates a problem for democracy. It is already hard enough to decide which projects provide the best direct public benefit. There are many more potential projects which primarily benefit a private party, but provide side benefits to the public, and which could be predicted to increase future tax revenue. How will we decide which io pursue?I also do not feel high confidence that the predicted future tax benefits will materialize with certainty. It is certain, however, that government will owe payments on the debt.Real estate development has not been working out that great lately and personally I do not believe the hype that everything is all better now. Local government finances are looking more and more awful.Overall this does not sound like a good idea to me.

John Gear

Roger, your enthusiasm for TIF is understandable, I once shared it. However, seeing how Portland basically used TIF to beggar its neighboring taxing jurisdictions has made me see the seamy underside. Essentially, Portland lavished money—free money, the best kind!—on development projects that were nothing but real-estate-bubble projects. Thanks to TIF, Portland has empty condo towers and brutally slashed basic services, especially for basic human services, like gang intervention (a fast-rising problem). There’s a fundamental problem with TIF that goes under the heading of “if it sounds too good to be true, it probably is.” TIF basically says “You don’t have to worry about paying for any of this, the FUTURE will pay for it.” As if the people in the future might not have other needs at least as compelling as building condo bunkers.I’ve suggested several times that the problem can be rectified by reducing the TIF revenue stream to account for the general increase in valuations that occurs simply due to inflation (i.e., if values rise 2% city-wide, then only increased value above 2% within the URA goes to pay the TIF bonds). Then, basic services like schools and mental health aren’t robbed to pay for shiny condos for rich people. I’m concerned that Sightline has adopted an uncritically pro-TIF stance that ignores the very real problems that this method of credit-card financing causes.

Roger

@John Gear, thanks for your comments. First, neither myself or Sightline have taken an uncritical stance on TIF (see especially:http://www.sightline.org/daily_score/archive/2010/12/03/tax-increment-financing-sprawl-and-urbanism). I think I have an awareness of the downsides of TIF: it involves some risk, it does generate some benefits for private parties, and there is risk that TIF might underwrite sprawl or horrible development patterns. Second, Washington’s budget based property tax system means that no other government will lose any revenue. No matter how TIF gets set up, adjacent and junior taxing districts will be able to collect revenue from the assessed value in the rest of the taxing district. That means there isn’t any transfer of scarce funding from schools, for example, to debt service for the TIF district. True, other property owners will have a slightly increased tax burden. But as you suggest, nothing is perfect. Legislation could address this to avoid that kind of tax shift. And that’s what Sightline is up to with TIF, watching the developing legislation closely and knowing the facts. True, I am enamored of value capture—borrowing today, making improvements, and paying back the loans with the value created by the benefits. But that’s true of energy efficiency upgrades as well as TIF. That’s why I thought Referendum 52 was such a good idea; it would have used debt to create public benefit today (jobs, money savings, reduced emissions, healthier teachers and students) by using future savings. Value capture is sustainable if done right. And that’s the point. We’ll be watching TIF in Washington to be sure it is more right than wrong, just like we did with energy efficienies for schools. The fact that TIF can have unsustainable outcomes doesn’t mean it shouldn’t happen. Instead we ought to be sure Washingyon gets TIF right.