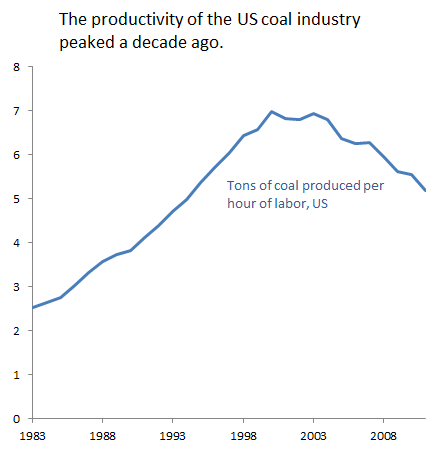

Interesting factoid: an hour of labor produces about 25 percent less coal today than it did a decade ago.

Declining labor productivity means rising costs and slimmer profits for coal companies—adding to the woes of an industry that’s already reeling from slumping demand. But it’s not like the coal industry is doing something wrong to make productivity fall. It’s mostly a matter of geology: like any industry, coal miners started on the easy stuff—the coal that was closest to the surface and easiest to mine. But as the easy coal gets mined out, it gets harder and harder to get new coal out of the ground.

That’s the picture for the US as a whole—but the national picture includes the high-cost mines in Appalachia. So what about the western US with its cost-efficient (though environmentally troubling) strip mines?

Same basic story. Here’s a chart of the productivity of the nation’s highest-volume coal mine, the Black Thunder operation in Wyoming.

And as for Ambre Energy—the would-be coal exporter whose shaky finances we discussed last month—the labor productivity of their Decker mine is at its lowest point since at keast 1983. No wonder the mine is losing so much money…

Jan Steinman

Looks like a harbinger of Peak Coal.

Better dig in and start growing your own food, folks. A lot of people are going to starve as fossil sunlight goes into permanent, irrevocable decline.

Ruben

Much more distressing than this is how much less energy is contained in each ton of coal. The really good stuff has been burned and now we are left with the dregs.

It is the same in oil and gas. The good stuff has been tapped. Even the much-heralded new discoveries are relatively puny, hard to get at and take a lot of energy to process.

Energy Returned on Energy Invested is making the cliff a lot steeper.

Clark Williams-Derry

Yep. The best analysis I’ve seen of global oil prices suggests that the price of oil is very closely linked to the cost of producing the “marginal” barrel of oil — just as economic theory would predict. So the reason oil is so expensive is just what you say: we’ve used up the easy stuff.

Paul Birkeland

Clark – Like the post, and the hypothesis makes sense (the the remaining coal is just harder to extract), but I’m not convinced. The start of the decline is when cheap natural gas started appearing, then the economy went kablooey, then the CO2 emissions regulations went into place. This could just be that the lower volume of coal mined over the last half dozen years led to lower efficiency in the mines, which is another possible explanation. Lower volume usually means lower efficiency in many things.

What can one look at to make certain that it is the harder-to-extract coal leading to this trend and not the lower volume demanded?

This may be overkill, but a linear regression that teases out the relationship between hours-per-ton (dependent variable) and total volume (dependent variable), might show something. If there remains a declining trend after taking out the impact of decreased volume, I’d say you could point to harder-to-extract coal with more confidence.

Clark Williams-Derry

Good points. I’m not the one to do a linear regression — no time, probably needs an expert.

But I also didn’t come up with the idea that easily mined coal is on the decline. For the east coast, this is essentially established fact — a common discussion in Appalachia, where declining productivity and harder-to-mine coal is sometimes welcomed because it’s believed it boosts jobs. For the Powder River Basin as a whole, this report has some interesting hints about long-term productivity trends.

As for temporal matches: the decline in productivity started well before the decline in production.

But you’re right, there’s a chance that declining production now is contributing to declining productivity, due to labor overhang.

TOM CIVILETTI

None of this is positive. We cannot wait for peak coal. There is plenty left to doom a good portion of humanity. And the harder coal becomes to dig, the higher its energy of production becomes, increasing its climate changing potential.

Bill Miller

I may be off base here, but this could be marginally good news. If we follow the logic of Professor Thomas Power’s economic analysis (if I understand it correctly), a higher cost for coal would mean less consumption in China, where most of the exports would be headed.

If the coal companies are able to pass on their higher costs then the Chinese could be expected to consider or seek alternative forms of energy that might be cleaner. Another incentive would be to invest in more efficient coal fired plants and phase out inefficient plants. All that theoretically means less pollution, but I’m speculating on that.

Of course, if competition among the coal companies in the Chinese market is so intense that these higher prices cannot be passed on then this idea is moot, and we still have a potential environmental disaster looming. Slimmer profits for the coal companies, but still the same amount of tonnage headed to Asia.