This post is an excerpt from Sightline’s recent report, Making Sustainability Legal: Outdated Rules that Stop Affordable, Green Solutions. It is an update of our October 2011 post on work licensing rules in the Pacific Northwest.

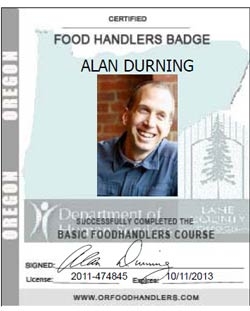

I got my Oregon Food Handler’s Badge. It took 52 minutes online and cost $10. Now I can work legally in Oregon restaurants!

If, however, I wanted to work braiding hair African-style in Oregon, or kickboxing for prize money in Washington, or selling timeshares in Montana, or promoting concerts in Alaska, or as an athletic trainer in Idaho or as scores of other things across the Northwest, I’d have to endure a more onerous licensing process.

Much more onerous.

Consider African-style hair braiding. As an article in yesterday’s edition of The New York Times points out, licensing rules in many states place tremendous and unnecessary burdens on would-be hair braiders. Oregon is one of those states. To braid hair for money in Oregon legally, I would need (in addition to actual braiding skills—no small thing), a hairstylist or barber license. Earning a cosmetology badge requires 1,700 hours of training and classes. That’s often two years of coursework, and it costs thousands of dollars. But this schooling is largely irrelevant to African-style hair braiding.

Amber Starks, an African-American model and hair braider in Portland, is a proud champion for black girls, wearing her hair in its natural state—unstraightened and uncolored—in ads and media appearances. In 2011, she decided to open a small business to braid black girls’ hair; she wanted especially to serve children in foster and adoptive placements, where parents may be unfamiliar with natural hair care for African-type hair.

Photo courtesy of Amber Starks, by Stephen Gilbert, Make up: Jenn Buslach, styling: Rebecca Westby, at Oaks Amusement Park (PDX).

Then (after reading Sightline’s original post on this theme), she was shocked to learn Oregon requires her to earn a beautician’s license. That’s right: state law in Oregon says that even a woman whose mother taught her how to do her own hair in childhood cannot braid foster children’s hair without a license.

Sadly, hair braiding is not the only case where outmoded rules make it unnecessarily hard for northwesterners to pursue a livelihood. Now, during the worst recession in living memory, is an ideal time to clear away these barriers to work. And licenses to braid are a great place to start the reforms. For one thing, requiring hairstyling licenses for braiders isn’t just Oregon’s practice, it’s the norm across North America. It’s the norm in Cascadia, too: Alaska mandates 1,650 hours of cosmetology training for braiders; Idaho and Montana, 2,000 hours.

For another thing, restricting braiding isn’t just onerous and preposterous. It may be racist. Hair braiders—most of whom are African immigrants or native-born African Americans serving African-American clients—do not cut, straighten, curl, or color hair, the skills commonly taught in beauty schools. What hair braiders do is braid hair. They weave in extensions and decorations, in keeping with traditions that originated in Africa. Licensing keeps skilled hair braiders from legally earning a living.

Amber Starks is not taking these setbacks sitting down. She is attacking Oregon’s hair-braiding rules. With Sightline’s help, she has recruited Rep. Alissa Keny-Guyer and Sen. Jackie Dingfelder (both D-Portland) to attempt reform in the 2013 legislature in Salem. Meanwhile, as of early 2012, Ms. Starks was considering a campaign to win a seat on Oregon’s State Board of Cosmetology, which rejected her request for a waiver allowing her to braid hair without a license.

Recently, she has been cleared to braid hair in Washington State, thanks to a legal effort. In 2005, after getting served with a public-interest lawsuit from the libertarian Institute for Justice, Washington’s Department of Licensing issued a statement “clarifying” its regulations in a way that suggested it was exempting hair braiding from licensing. In late 2011, Ms. Starks inquired with the Department about the details of hair braiding rules, hoping she could open her business in Vancouver, Washington. The agent she spoke with said she was allowed to braid hair without a license, but only if she never uses a comb, brush, barrette, or rubber band. In April 2012, following another inquiry from the Institute for Justice, the Department of Licensing sent a letter stating that information was incorrect. The agency “re-clarified” its position that natural hair braiders do not need a license to practice in Washington.

British Columbia is another Cascadian jurisdiction that’s cleared the path for braiders. In 2004, legislators in Victoria—failing to see any compelling reason to continue licensing beauty workers at all—simply ended regulation of barbers, hair stylists, manicurists, and skin-care estheticians.

De-licensing did not mean the end of training and standards. The BC Beauty Council, a trade association, immediately began offering voluntary certification to salon workers, and most of them continued to seek it. The difference is that customers can decide for themselves if they care about the Beauty Council seal of approval. In the age of Yelp and other social media ratings, state licensing of hair cutters no longer makes sense, if it ever did.

The legitimate purpose of occupational licensing is to protect the interests of the community from ill-trained, inexperienced workers behaving badly. We want to make sure, for example, that midwives, bridge engineers, and pesticide applicators know what they’re doing. Any of them can cause lasting, far-reaching harm. Just so, we want to know that food handlers understand how to keep the food supply free of salmonella and other food-borne illnesses, which kill thousands of people in North America each year. (I, for one, think getting a Food Handler’s Badge should take much more than 52 minutes!)

Reasonable people can disagree about exactly where to draw the line between state licensing and occupations regulating themselves. Construction laborers don’t currently need to secure licenses, nor do mechanics, janitors, couriers, carpenters, event planners, receptionists, painters, waiters, stone masons, or cooks. Some of these occupations have associations and training regimes that offer certification and credentials on a voluntary basis, but they are not legally required. Accountants, medical doctors, and attorneys, on the other hand, have official sanction to back up their own professional self-regulation. State bar associations, not states, administer bar exams, yet states enforce the standards.

Over the years, the line has tended to migrate toward more state licensing, such that perhaps 10 percent of all jobs in the United States are governed by occupational licensing, according to the Institute for Justice. What share of those occupational licensing requirements are unneeded isn’t clear, but at a minimum, braiding hair should not require a license. The same goes for athletic training, kick boxing, and selling time shares. Likewise, is there any legitimate public purpose served by Washington licensing auctioneers? Telephone solicitors? (You can find more examples of Cascadian licensed occupations here: Alaska, British Columbia, Idaho, Montana, Oregon, and Washington.)

The reason for the growth of licensing is not simply protecting the public interest but, rather, protecting the private interests of those workers who already have their licenses. Seattle attorney Jeanette Petersen describes the pattern:

Typically, licensing boards are comprised of members of the regulated profession, with the coercive power of government at their disposal. As a result, licensing requirements often exceed valid public health and safety objectives, and instead are used to reduce competition threatened by newcomers. As economist Walter Williams observes, these laws and regulations “discriminate against certain people,” particularly “outsiders, latecomers and the resourceless,” among whom members of minority groups disproportionately are represented.

Nobel Prize winning economist George Stigler would recognize this pattern as an instance of regulatory capture. Washington’s statutes give authority over beauty occupations to a Cosmetology, Barbering, Esthetics, and Manicuring Advisory Board. By law, the board must include nine members: one unaffiliated consumer and eight representatives of segments of the trade. The foxes, in other words, are guaranteed the right to guard the hen house.

These cartel-like politics are what lies behind outrageously divergent licensing rules: 1,600 hours of instruction to get a hair-cutting license in Washington, for example, but only 130 hours to become an Emergency Medical Technician. In fact, you can earn certification as a firefighter in Washington after just 385 hours of coursework—one-fourth the time it takes to become a stylist. And, as I said, it takes 1,700 times as long to win legal permission to braid hair in Oregon as it does to get a Food Handler’s Badge.

To our credit, Cascadia does already have a reform leader in its ranks. British Columbia stands out among Canadian provinces in de-licensing. It has shifted not just beauty workers but many other trades from official licensing to voluntary certification. That kind of streamlining is exactly what other Northwest jurisdictions can do to clear barriers to gainful employment.

Sadly, legalizing African-style hair braiding, deregulating kickboxing, and otherwise pruning the excesses of occupational licensing in Cascadia is not going to be enough itself to wipe out double-digit unemployment or revive family income growth. A thorough pruning might, however, help thousands of Northwest workers each year, and, in times like these, that’s an opportunity too big to ignore.