Climate change is regressive by nature, but solutions don’t have to be. A fair cap-and-trade system can be progressive, broadly sharing both the burdens and the potential benefits of preventing climate disruption. We have an enormous opportunity to get climate policy right—and we know how it can be done.

In fact, smart policy is our opportunity to fight climate change and minimize economic injustice. This is the single most important economic fairness issue facing Cascadia right now: more important than reforming payday lending, more important even than reforming health insurance. It’s what every advocate for economic opportunity should be losing sleep over—but then jumping out of bed to help shape the solution.

The most needed measure for minimizing climate disruption is a firm cap on emissions of greenhouse gases and a mechanism for putting a price on those emissions. In short, climate pricing. We need to make prices tell the truth about the climate.

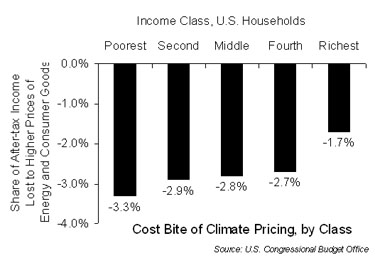

Truthful pricing of carbon emissions, of course, means higher prices for fossil fuels. And higher fuel prices are regressive. They hit working families the hardest. By a lot.

The U.S. Congressional Budget Office’s rigorous analysis of the different approaches to climate pricing estimates that a carbon charge steep enough to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 15 percent would take about 3.3 percent of low-income families’ after-tax money. James Boyce and Matthew Riddle of the University of Massachusetts peg the cost to working families even higher.

“Grandfathering” carbon-emissions permits—giving them away to historic polluters, as many energy interests propose to do—would write this redistribution of wealth into law. Under this version of Cap and Trade (Boyce and Riddle call it “Cap and Giveaway”), fossil fuel prices would rise. (They will rise under any firm cap; in fact, they’re likely to rise even without a cap, as they have done in recent years.) Families would pay more for their energy—and their food and other energy-intensive consumer goods. Energy companies, flush from high prices, would reap huge windfall profits. These windfalls would ultimately accrue to the shareholders of energy companies, who are mostly rich families. (This scenario already played out in Europe.)

Under Cap-and-Giveaway, the richest fifth of families would pay more for their energy, just like everyone else. But their stock portfolios would get so much fatter that the net effect would be an additional $1,200 a year per person, according to Boyce and Riddle.

Yep, under Cap-and-Giveaway, the rich get richer, and the poor get poorer. This chart from Boyce and Riddle shows roughly how much. (Unlike the previous chart, this one reflects the impacts of massive windfalls for energy company stockholders and various other side-effects of Cap-and-Giveaway, and expresses losses and gains as shares of total household expenditures rather than income.)

|

I don’t know about you, but I can’t abide a future like that, where the rank injustice of climate change itself is compounded by a system that takes money from working families and gives it to rich ones. It’s Robin Hood in reverse. It’s the New Deal’s evil twin.

Think about it: Cap-and-Giveaway means that the orderlies in our hospitals will hand hundreds of dollars a year to the surgeons they clean up after; that farmworkers in our vineyards will hand piles of cash to the people who drink their most-expensive vintages; that the janitors in our airports will deliver annual checks to airplane owners; that retired grocery store clerks will pay the moorage fees for yacht owners.

It doesn’t have to be this way, as Boyce and Riddle demonstrate. If we auction rather than give away permits to emit greenhouse gases, the public will claim for the common good the proceeds of higher energy prices. And the public can then return much of the resulting revenue to families, on an equal per person basis. Boyce and Riddle call this “Cap and Dividend”; others call it Sky Trust. Everyone pays more for their energy; everyone gets a dividend check from the new Climate Trust Fund. A $55/ton carbon dioxide charge would yield almost $700 a year per person. It’d be like the Alaska Permanent Fund, which pays out an annual share of oil earnings to each resident of the state.

The net effect of Cap and Dividend, shown in this chart, is to take the sting out of climate pricing for low- and middle-income families. They pay more for energy, but their climate dividend covers the expense.

That’s not going to end poverty in Cascadia or reverse the widening income gaps that plague our continent. But it’s a step toward climate fairness; it’s enough to offset some of the unfairness of climate change itself.

And it’s proof that how we set climate policy matters as much as that we set climate policy.

Cap and Dividend isn’t the only way to make climate pricing fair. I’ll describe another workable approach next time.

Thanks to Clark, who did some of the research for this post.

See also:

Alan’s first post on climate fairness

Morgan Ahouse

Thanks for this great topic!I too would like to see the emission cap auctioned as much as possible, but what to do with the resulting revenues is a second question where I find myself inclined to disagree with Alter and Boyce. The essential difficulty I have is their recommendation that auction proceeds be plowed right back into the economy, yet the economy we have now is the source of the problem(s) we’re trying to fix, both for its regressivity and for its polluting nature. They don’t say it exactly this way, but returning auction proceeds to consumers doesn’t seem much different in its back-end effects than those from the tax stimulus package bouncing around congress right now. The effect I see is consumers spending their dividend or refund in exactly the same way they do now (except for some different signals on energy prices), thereby reinforcing the current economy. While I support redistribution for equity purposes, I think there’s a missed opportunity to further affect the nature of the economy beyond the price signals provided by a cap and trade system. The missed opportunity is directing auction proceeds toward policies that, in aggregate, both change the nature of the economy and address the regressive impacts of climate change and climate change policies—no simple charge. I would be more inclined to plow auction proceeds into, for example, green-collar jobs for low and middle wage workers, into transportation choices that offer alternatives to roadway tolls and alternatives to vehicle ownership more generally, into community redesigning that affords walking and it’s accompanying progressive health benefits, and into building affordable housing near work centers. While the progressivity of this stuff is really hard to measure, I think policy should work for us at both the front end and the back end.

Alan Durning

bahouse,Thanks for your thoughts. My next post will talk about a fairness strategy that leaves most auction proceeds available for spending of the type you mention. I’ll dig deeper into the equity effects of some of your other ideas too.My impression from research so far is that we’re going to need cash transfers at least to poor families in addition to whatever public investments we make in other programs. Otherwise, working families will end up worse off.More to come . . .

Dave Ewoldt

I feel like I’ve just entered the Twilight Zone.Cap-n-trade the road to economic fairness? What you’re really saying is that by throwing the peasants slightly larger crumbs, they should gladly embrace their increasing body burden, because we can’t do anything that might cause lasting harm to a growth economy. Large centralized corporations are going to continue poisoning the planet, but this is really alright because government will grab some of their obscene profits and pass them on to the consumer so they can afford more Cheese Puffs, Paxil, and Prozac.There is no moral or ethical argument that can justify continuing to pollute the planet, only an economic one. And thus it seems you have just added your voice to those who maintain that profit is more important, and more deserving of protection, than either people or planet.I thought I only had to put up with this nonsense from mainstream enviro groups like NRDC and Sierra Club?

Alan Durning

Dave Ewoldt,Um, huh? I do not understand you.

lesgldst

Please explain why Cap and Trade (which is complex enough to give marketeers much opportunity for manipulation) is preferable to a simple carbon tax, the proceeds of which can be used for all the benefits cited above.

Clark Williams-Derry

Lesgidst -I think that’s a great question. My response:Cap and tax are two flavors of the same basic idea—the polluter pays principle, applied to climate change.Carbon taxes have the advantage that they’re predictable for businesses and consumers, and fairly straightforward to administer. There’s a big political disadvantage—some people just don’t like the label “taxes,” even if they’re willing to support policies that have the same effect as taxes. I think that’s irrational, but also real. But taxes have a deeper, substantive disadvantage: we don’t know *in advance* how much it will cost to achieve any given level of emissions reductions. Estimates vary for the “right” level of tax to achieve deep emissions reductions—and they vary not by a little bit, but by a lot. Like an order of magnitude. So policymakers will probably need to continually adjust the level of the tax—and possibly increase the tax annually, especially if they start out too low. That’s a recipe for perpetual political battles over the “right” level of the tax. In the meantime, as we get the tax level steep enough to make a difference, we’d be wasting valuable time at achieving real reductions. You’re right, a cap is more complicated to administer than a tax; but, in the end, it functions as a self-adjusting tax—that is, the level of the tax (ie, the price of allowances) is precisely calibrated to achieve any emissions target. One way to think about this: Imagine a tax on fossil CO2 emissions. All emissions get taxed; and a simple tax system would focus “upstream,” when fossil fuels enter the economy. Major fossil fuel companies have to track the carbon content of whatever they sell, and pay a tax on it. Those price signals from the tax discourage emissions throughout the economy—from the fossil fuel companies themselves, through to end use consumers.Now, instead of “tax” in the last paragraph, think “buy allowances.” Fossil fuel companies don’t pay a tax, they buy allowances. The supply of allowances in any given period is fixed & limited, so the price of allowances self-adjusts to achieve the precise level of reductions, somewhere in the economy, that’s required by the cap.The nice thing about Cap & Share (or Cap & Dividend) is that, even if someone manipulates the market and prices rise quickly, most folks—especially the poor—get *better off*. When allowance prices increase, that just means that there’s more more money to be shared. Wacky, I know, but a nifty result.That’s long-winded, sorry. But the basic reason we like cap & trade over taxes is the certainty in the result—the cap guarantees that we’ll achieve particular emissions goals. A tax doesn’t.For more about this idea, see here.

Alan Durning

The Alaska legislature is considering a bill to rebate much of the influx of petrodollars its been inundated with, in equal per-capita dividends of $500. This isn’t Cap and Dividend, but it is promising. Here’s the article.

Alan Durning

The Alaska legislature ultimately decided against per-capita dividends, but did provide funds for low-income dividends (as in Cap and Buffer) and for weatherization (as in Cap and Caulk).

Alex

I can see a lot people having a problem with the U.S. espousing cap and dividend in that it might favor countries like China, or every other country but the U.S, and result in worsening pollution outside the U.S. For example, if the upstream corporations (like Exxon if I’m understanding correctly) end up charging more for oil, and products made in the U.S. from oil are more expensive, people are even more likely to buy products that were made in China with cheaper oil and have a lower retail cost (assuming shipping costs remain reasonable). This will result in China’s terrible pollution getting worse and American companies closing up shop. Am I totally off track or making bad assumptions?

Mike Lemay

Confiscating corporate resources is not the answer to climate change. Cap and Whatever will only undermine the profitability of the energy industry which ultimately affects every household in the US. I don’t know where the misconception that utilities are rich came from, but many are right on the edge, operating on a shoestring. It’s extremely difficult to provide energy at a reasonable and stable price to consumers when the cost of fuel to generate it moves so dramatically on the market, besides most utilities are regulated by their state’s Public Utilities Commission. Most of this legislation has nothing to do with eliminating greenhouse gasses, as a matter of fact many “require” energy providers to implement technologies that don’t even exist! All this legislation is about the redistribution of wealth. Either moving money from the middle states to the coasts in the case of cap and trade, or into the bottomless coffers of the government in the the case of cap and dividend. Don’t be deceived by the promise of an $1100 annual dividend that will cost you $2000 over the course of the year in higher electric rates, groceries etc.If the government were really interested in curbing carbon emissions they would implement “incentives” for companies to lower their output. Incentive not taxation is the mother of invention.