A recent article in the New York Times highlighted a topic I’d been hearing a lot about lately: “passive house.” Passive house is a methodology that takes advantage of materials and design to dramatically limit total energy consumption by reducing the need for heating and cooling. It’s ‘passive’ because keeping a building warm or cool doesn’t require flipping a switch or adjusting a thermostat. In other words, it’s self regulating. The building—because of materials and design—retains heat when it’s needed most without the need to heat up cold air and move it around.

A recent article in the New York Times highlighted a topic I’d been hearing a lot about lately: “passive house.” Passive house is a methodology that takes advantage of materials and design to dramatically limit total energy consumption by reducing the need for heating and cooling. It’s ‘passive’ because keeping a building warm or cool doesn’t require flipping a switch or adjusting a thermostat. In other words, it’s self regulating. The building—because of materials and design—retains heat when it’s needed most without the need to heat up cold air and move it around.

The passive house concept is emerging as an important strategy to reduce emissions and energy use in the building sector.

I should say first of all that almost everything I know about passive house comes to me from two local architects who are newly certified in passive house design. Rob Harrison is actually right in the Vance Building where Sightline’s offices are located and Jim Burton has been leading a number of efforts for the Northwest Eco Building Guild (I’ve written about the Guild before). I know they’ll add, correct, and expand my points in the comments section. One of the first things that both Harrison and Burton make clear to me is that passive house is a somewhat misleading term because it doesn’t just apply to houses but to all types of buildings. And passive house is a methodology not an adjective. It might have been better left in its German form, Passivhaus.

How does it work? Here’s a rundown based on Burton’s description of the Passivhaus Standard for Seattle’s Carbon Neutrality efforts. Passivhaus buildings will have:

- A super-insulated envelope (in our climate, perhaps an R-48 wall, R60 roof);

- High-performance triple-glazed windows (U-value .15 or lower);

- Reduction or elimination of thermal bridging;

- Super airtight construction (has to meet Air Change Rate of .6 ACH @ 50 Pascals, almost unheard of, and probably the hardest part of building a Passive House);

- Heat-recovery ventilation; and

- Use of passive sources for heat gain – solar of course, but also lighting, appliances, and people in the building.

Some of that is pretty technical stuff. But a Passivhaus building would essentially be off the grid, using natural sources of heat to keep the building warm, including the body heat of people in the building and sunlight, for example. Getting Passivhaus right is complicated and requires expertise, which is why there is a certification program. But once Passivhaus is implemented in design and construction, the savings are demonstrable. According to Burton,

The super-efficient envelope reduces the heating load so much that the building does not need a conventional heating system. In practice that heating is often provided by a small coil – electric or hydronic – in the code-required ventilation system. The Passive House Institute (PHIUS) likes to say that the heating system in a PH is limited to 2000 watts, the size of a hair dryer.

Intrigued? So am I. Passivhaus can be more expensive because of the materials and the design. But advocates argue that the extra cost is far exceeded by the energy savings. That’s important. We still have to figure out how to pay for the up front work which can be expensive, but while we are figuring out how to finance the efficiencies that are good for the planet, our economy, and the health and wellness of people, I am glad to add Passivhaus to my list of things to learn more about.

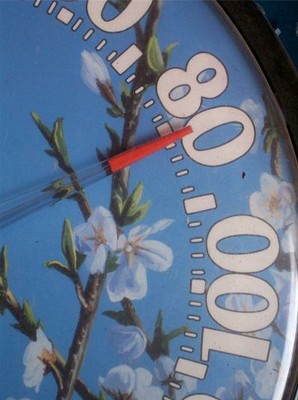

Photo credit: cohdra from morguefile.com.

Brian

It used to be the case that “passive houses are for active people.” Because, of course, if you want this program to work you have to run around in the morning opening your big thick insulated curtains on the south side in the morning, and remember to close them as soon as the sun is off them (and there is more activity to it as well).I’d be interested to hear from your resources what progress has been made in making this style of construction available to lazy people.

Rick

Actually, getting the envelope airtight is fairly easy if attention is paid to details and a blower door test is done before insulation and sheetrock. It’s also the most cost effective part of the Passivhaus program for our climate.

Stacey W-H

I’m interested in learning about the additional complexity of retrofitting existing homes with passive solar. Anyone out there have any links, case studies or research to share? Anyone out there have experience with retrofitting historic homes? Talk about a niche market! If I ever find the right architect, I’m sure I wouldn’t be able to afford her/him.

Rob Harrison AIA

@Brian: You have deftly illustrated (thank you!) how easily “Passive House” is confused with “passive solar.” It’s easy to see how the confusion arises. I believe the Passive House Institute US made a mistake in literally translating “Passivhaus,” the German name for the standard, to “Passive House” in the United States. The choice of the term by Dr. Wolfgang Feist, originator of the standard, was in fact a nod to the passive solar, super-insulated homes built in Canada and the US in the late ’70’s and early 80’s. As with passive solar, buildings designed to meet the Passive House standard are finely tuned to their site, take into account the path of the sun, and use the sun’s warmth to provide some of the heating energy the building requires. Unlike passive solar, the Passive House standard does not require or even encourage lowering thermal blankets over windows, Trombe walls, “thermal mass,” earth-berming, or vast areas of south-facing glass to the exclusion of windows facing other directions. This is good, because these techniques don’t work particularly well in Cascadia.Passive House is simply a performance standard for energy use, not an approach to or style of building. Those performance standards are:* Use less than 4.75 kBTU per square foot per year on site for space heating.* Use less than 38 kBTU per square foot per year for source energy, which takes into account generation and transmission losses from various sources of energy, including hydro, common here, and coal, common back east. * As stated above, an air leakage rate of less than 0.6 ACH at 50 Pascal.There are a couple other recommendations—for the energy efficiency of heat recovery ventilators, for example—but that’s really all there is to it. It is definitely not a prescriptive checklist of insulation levels and window performance standards, the point being that those things will vary with each site and climate. This standard, which is completely achievable today, results in a 90% reduction of energy use, compared to typical buildings. Note that energy use is calculated *before* taking into account any on-site generated energy. So you can’t get to Passive House by designing a low-performance building and plopping a bunch of photovoltaic panels on the roof. Projected energy use is calculated using a complex Excel-based spreadsheet called the Passive House Planning Package (PHPP). Data about the building, from each layer of building material in the building envelope to the number of say toilets in a school building, is entered into the spreadsheet’s 30+ pages. (The cooling effect of flushing toilets—bringing cool water into the building—is taken into account!) For the energy wonks out there, note that square footage is counted according to the German standard, which results in a smaller number for square footage of any building, so the energy use is 20% to 30% better than the above numbers might suggest.The Passive House house we designed and permitted in Pierce County (but which, sadly, did not get built) would have met the energy standards for the 2025 tier of the 2030 Challenge. @Stacey: Retrofits are much harder, but doable. It only really makes sense (At this stage of the game anyway) if you are removing or replacing the siding. There are 15,000 certified Passive House buildings in Europe, but so far only thirteen in the United States. We have a lot to learn for sure, but the potential of Passive House is enormous.

Rob Harrison AIA

Oh, and Roger, a Passive House is not necessarily “off-the-grid.” That term is usually applied to buildings that generate their own power. (And are occupied by hippies…?) It is much *easier* to make a Passive House net-zero, or energy self-sufficient, because the amount of energy that needs to be made up (only the last 10% of the 90% reduction) is smaller than with other standards.

Roger Valdez

Thanks Rob. I knew you’d only make this discussion better.

mike eliason

PHIUS definitely made a judgement error in literally translating Passivhaus, and judging from the comments in the NYT article, there is going to be a major uphill battle to clarify what it really is. the issue of financing passivhaus projects is a tricky one. presently, the cost to achieve passivhaus in the EU is significantly cheaper for a number of reasons (gov’t mandates, stronger demand, better exposure) but the big one is that buildings in the EU aren’t allowed to be built to the horrible performance standards allowed here in the US. let’s face it, our energy codes are pathetic, especially by comparison.also, passivhaus can be easier to achieve with larger projects like multi-family, schools, office towers, fire stations, etc. and unlike LEED, significantly decreases energy usage. the use of HRVs/ERVs in passivhaus projects allows for cleaner air than leaky buildings (due to filtration), and they have significantly reduced levels of radon concentration.it’s pretty much like hitting the trifecta, no?also, i read recently the number of PH projects is approaching 20,000. and that was buildings, not units. a few thousand Passivhaus consultants have reduced more energy in more buildings than over 100,000 LEED APs.

Beth

Excellent post Roger, and Rob, excellent exposition on the Passive House concept and its misconceptions. We have retrofitted a 1960s home into a beautiful modern farmhouse. It was expensive, but it is, after all, a high end custom home in an expensive marketplace. Projects in Utah and Portland have already demonstrated that you can build for just about 5% over standard construction costs. Roughly 90% of the materials were all locally sourced with the notable exception of the windows and doors, which were imported from Germany. US window manufacturers are not there yet in terms of glazing but there are firms working on this. Once US manufacturers and distributors get on board with making and selling efficient products, costs WILL come down (and will supply green jobs to boot).You can see the house here:http://bit.ly/bTCu1H And I agree, Passive House is an unfortunate name and has caused no end of confusion.

JC

SeriousWindows have really become the standard in passive house – many in the NW and some now popping up in the NE – and it’s not just about high Rvalue – it’s about SHGC and the importance of placement and orientation of the windows (of the whole house, if you’re building new, for that matter). There’s info on the seriouswindows web site but better stories about projects and videos here http://blog.seriousmaterials.com

Rob Harrison AIA

@Beth: I read about your house on Linda Whaley’s blog today. (http://existingresources.wordpress.com/) Beautiful project! I liked your take on the misconceptions about Passive House proven wrong by your retrofit, worth repeating here:”1. You have a super tight envelope and therefore can’t open windows. Not true.2. You can’t have a northern view, i.e. windows. Not true.3. You must build a small, utilitarian box. Not true.4. You can’t have a fireplace or hood over your stove. Not true.”@JC: There are a number of windows available in the US that work well in Passive House. Serious makes one. Dan Whitmore used Cascadia Windows in his Passive House in the Rainier Valley which, like Serious Windows, are fiberglass. We have looked at Zech, Optiwin, and Enersign windows, all superb European aluminum-clad wood windows distributed in the US.

Eric Schinfeld

I actually posted about this last week…and used the same joke in my post title! http://prosperityblog.wordpress.com/2010/10/01/lets-get-passive-about-energy-efficiency/

Seattle voter

Great stuff but let’s get a handle on costs. Re Beth’s wonderful California remodel: “…it should be noted that this small, smart answer didn’t come cheaply: the 18-month long project cost $1.2 million to complete.”Most of the progress on this front, at least in greater Seattle, will be in retrofit and remodel projects—if the costs come way, way down. Under growth management, there shouldn’t be vast numbers of new SF housing projects.Let’s also expand this discussion to multi-family structures, where more of the new development will be taking place

Bill B

Sadly with Seattle’s lowrise changes racing to completion we may be missing an opportunity to include performance based criteria to this building type. Currently LEED is used as an incentive for added density. The Planning Commission recommended ASHRAE 186 rather than LEED.In this day and age we should be setting the bar higher – it will pay off for occupants and the planet in the long run.

Rob Harrison AIA

@Eric: I like the “sailboat” vs “powerboat” analogy. I’m going to use that….:)@Seattle Voter: Several of the (ahem) 13 certified Passive Houses in the US have been done for low-income housing groups. Small sampling and a different market, but for those projects Passive House added less than 5% to the construction cost, which was in the range of $100/SF. Dan Whitmore’s Passive House on Courtland Place (behind the Safeway on Rainier Ave S.), the first in Washington State, is not an expensive house. Follow the construction here: http://existingresources.wordpress.com/seattle-passive-house-from-the-beginning/@Bill B: I completely agree. Passive House is *almost* trivial to achieve in multi-family. That any new building doesn’t use Passive House (or another approach that achieves the same results) is an opportunity lost for the life of that building.

Bryn Davidson

We’re building all of our houses and laneway houses to a ‘near-passivhaus’ standard: ~R40 SIP walls, ~R50 SIP roof, triple glazed windows and – in most cases – an HRV and drainwater heat recovery. The cost of the better envelope is offset by a radical downsizing in the heating system. They’re not perfect net-zero buildings, by any means, but we’re trying to make this type of construction competitive with the 2×6 structures that other builders are putting up. You can see construction photos on our Lanefab facebook page.

ph0rque

[Passive House] doesn’t just apply to houses but to all types of buildings.Is it possible to create a Passive House greenhouse? Also, what about Passive Houses in the South, where cooling is a bigger issue than heating?

mike eliason

facetious… but there have been greenhouses cum passivhaeuser.http://www.solidar-architekten.de/projekte/altbau/solidar-glashaus-coswig.htmlconceivably you probably could make a greenhouse that reaches passivhaus, but why would you? it’s not needed.passivhaus works in cooling dominated regions like the south (e.g. louisiana)http://www.treehugger.com/files/2010/07/the-south-gets-first-passive-house-beats-california.php

ph0rque

conceivably you probably could make a greenhouse that reaches passivhaus, but why would you? it’s not needed. From what I understand, the bottleneck to having year-round greenhouses in northern climates is the need to heat them in the winter months. A passive greenhouse would solve that issue.

MicheLynne

Great post and discussion. But I need some more enlightenment.According to the post, “Passivhaus buildings will have…passive sources for heat gain – solar of course, but also lighting, appliances, and people in the building.”So I’m wondering, if the buildings are expected to have heat gain from lighting, beyond solar, then what kind of *lights* are being used? It’s my understanding that CFLs don’t produce much heat, but they save a tremendous amount of energy. And incandescent lights produce a lot of heat, but they also burn a lot of energy. So, maybe candles are being used?…

mike eliason

heat gains from process (waste) energy, akacatsdogspeopleapplianceswater heater/storage tankslightsit all adds up to a fairly significant percentage of total space heating needs (yes, even with CFL/LED/low voltage, etc), in some instances over 25%. i think a CFL wastes about 15% energy to heat.you can use candles. there is a really stunning cross laminated timber duplex in sistrans (AT) that utilizes a modern ethanol ‘fire’ to heat the house on coldest days:http://bruteforcecollaborative.wordpress.com/2010/07/25/phbdw-passivhaus-bau-der-woche-07/

MicheLynne

That Austrian duplex is gorgeous! My first impression, though, was that all that wood and open space would create an echo-effect as people walk across the floors. But according to your blog, the super-insulation from the CLT panels “ensures a quiet…interior.” And maybe people remove their shoes anyway, to keep the floors looking nice!

Jim Burton

Even though Passive House is not a comprehensive Green Building methodology or rating system (Ã la LEED for Homes, or Built Green), presumably a Passive House would be using energy-efficient lighting such as CFLs or LEDs. In any case, whatever is being used for lighting is taken into account in the Passive House energy modeling. It is true that incandescent lighting would actually help during the heating season (in the sense of lessening your need for makeup heat, and the potential size of your heating system), but it would hurt you during the cooling season.

MicheLynne

Interesting. So, it sounds like a “seasonal” lighting system could work best, incorporating different types of lights at different times of year, depending on the weather.

Rob Harrison AIA

@Michelynne: Though it’s an interesting idea, it would not be necessary (or practical) to switch out bulbs by season. Incandescent lamps are on their way out already, and probably ought not to be counted on in any building that hopes to be around for the next 10 years, let alone 100. In any case, the need for heat sometimes conflicts with the need for light—at night, for example. 🙂

MicheLynne

Hi Rob, I think my passiv(dream)haus would have color-coded lightswitches symbolizing the heat-factors of the pre-installed lightbulbs. For instance, the red lightswitches would turn on the hot lightbulbs (such as the halogens), and the turquoise lightswitches would turn on the cool lightbulbs (such as the CFLs).