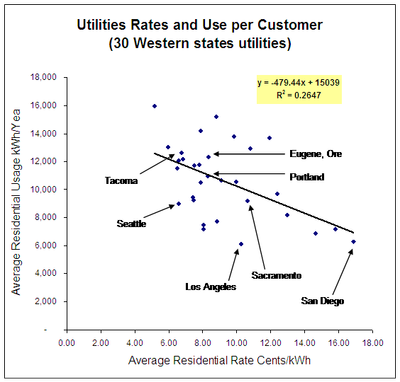

I’m going to geek out for a second. But first, check out this graph:

I suppose there are two lessons:

1. Price and consumption are not perfectly correlated. Clearly there are many non-price factors affecting electricity consumption. (These include, at least, the local climate, building size and type, and local energy efficiency policies.) But still…

2. Price definitely affects use, and the fit gets better as you move up the price axis. The more expensive electricity is, the less likely consumers are to be profligate.

In energy circles it’s sometimes alleged that consumers are price insensitive or economically irrational about consumption. There’s some truth to that, but it’s only a partial truth.

These charts help demonstrate why carbon pricing can be effective. Putting a price on carbon—or a price on energy — acts to reduce consumption. Price is not the only factor and it may not even be the biggest factor, but it does appear to matter. And it appears to matter more above about 10 or 12 cents per kilowatt hour.

This hooks into a larger debate in the Western Climate Initiative.

Many utilities are arguing that they should get free carbon allowances on the grounds that they are rate-regulated, and so they will not (or cannot) take windfall profits. They even deploy arguments about consumer protection, pointing out that they can protect ratepayers by not passing on price increases. That sounds pretty good at first, but it doesn’t work so well in practice. (For the definitive rebuttal to these arguments, see Clark’s excellent post.)

The point is, for carbon policy to work fairly, the price of energy needs to go up to stimulate appropriate conservation. When the price of electricity is low, as it is in Seattle for example, even the most aggressive efficiency and conservation programs yield modest results. (And Seattle truly does have industry-leading programs.) Residents of California’s air-conditioned cities consume less electricity, on average, than residents of either Seattle or Portland.

Luckily, under smart versions of cap and trade, higher energy prices can be good for consumers—as counter-intuitive as that sounds. Here’s how: WCI should auction carbon permits and allow utilities to pass on the prices to consumers. Then—and this is critical—WCI should refund the money to citizens, especially those below median income. These refunds (two flavors here and here) can easily make most energy consumers whole again. With cap and rebate, the “price signal” of carbon gets communicated through to consumers, but with no net pain for most.

(A footnote: there might still be inequities in a system like the one I’ve described. If you’re a Seattle City Light customer, for example, your hydro-based utility needs to purchase very few carbon permits and so there would be only a very modest price increase at most. That would mean a continuation of the limited price incentive to conserve. But your neighbors in western Washington would see higher rate increases, and your friends in, say, southern California would see much higher increases. We might need to iron out these geographic inequities.)

Want more evidence of the relationship? Okay, then. Here’s a chart for the 200 largest utilities in the United States. You see very much the same price-consumption trend as you see in the West. And the correlation appears to get stronger as prices get higher.

The data for these charts come from energy economics guru Jim Lazar. Jim also provided original versions of these charts and then I re-designed them to make them a little easier to read. The conclusions in this blog post are, of course, mine and not necessarily Jim’s.

Spock_rhp

I suggest that your graphs be adjusted for the mean daily difference between 75 degrees and the actual daily average temperature for each city and the proportion of houses using electricity for heating/cooling.The most energy expensive tasks are changing the temperature of something [heating/cooling] and moving water [pumping large amounts of it]. It stands to reason that energy usage will be higher in the most extreme climates [Phoenix and Fargo, ND] and especially in those with few or no alternative sources of energy for the desired task [you can heat with oil, gas, wood, or even coal, but the only likely method of cooling a house is electricity].I strongly suspect that people make pretty good decisions on spending their money, subject to the things they can’t change, or can’t change cheaply.I suspect that graphs adjusted as I suggest would strengthen your argument [show less dispersion from the average line].[MBA/CPA]

jonesey

Since we’re geeking out, I let’s talk about something from Econ 102: substitution. When electricity is cheap, it makes rational economic sense to use it for everything, including home heating. When electricity is more expensive, using oil or natural gas is more attractive. In order to get at overall energy consumption v. price, you would have to include home heating oil and natural gas consumption, then calculate an average price per BTU.I know from personal experience in the northwest that tons of people installed electric baseboard heaters when electricity was 2-3 cents per kWh. It didn’t make sense to do anything else. Your graph may be showing residual effects of those choices.

James

(A footnote: there might still be inequities in a system like the one I’ve described. If you’re a Seattle City Light customer, for example, your hydro-based utility needs to purchase very few carbon permits and so there would be only a very modest price increase at most. That would mean a continuation of the limited price incentive to conserve. But your neighbors in western Washington would see higher rate increases, and your friends in, say, southern California would see much higher increases. We might need to iron out these geographic inequities.)I disagree with the concept that utilities that are already carbon free should have to “ironed out”. If you do that, you are taking away the incentive for a utility to invest in solar, wind geothermal, etc. And if a utilitiy is already 100% carbon free, why would we even care? Let’s applaud that utility. Don’t seek a way to “iron out the inequity”. Reward good decisions, don’t penalize them.The regions of this country that have utilities that are carbon free, those same regions will likely have lower utility rates in a cap/trade system. That will also be more attractive to businesses that are making decisions on where to locate new facilities. So those areas that have the lowest electric rates will be more attractive economically.To some extent, let’s make it beneficial to have a zero/low carbon electric grid. If the goal is merely to punish everyone with high rates, then that serves no purpose. If some regions have low rates because of hydro and are zero carbon, that is a GOOD thing.

Tom L

Appliance and building standards would do more than high electric rates. Perhaps appliances and insulation could be upgraded on sale, as toilets are in some parts of the country. Also, an electric rate allowing low costs for modest needs, based upon occupancy and living area, and higher rates for additional use might be more equitable than a blanket rate increase.