Editor’s note: The article in Sightline’s latest research updates email incorrectly stated that wolves were introduced to the region “less than two years ago.” That should have read “less than two decades ago.”

Editor’s note: The article in Sightline’s latest research updates email incorrectly stated that wolves were introduced to the region “less than two years ago.” That should have read “less than two decades ago.”

Last year was the first in which sport hunters were allowed to legally shoot the gray wolves that were first reintroduced to Montana and Idaho in the 1990s. The hunts made some locals feel as if they had control over an unwelcome predator they never wanted in their fields and forests. To others, shooting a wolf is a sacrilege, one that threatens to undo decades of work to bring them back.

So how did the wolves fare?

At the end of 2009, there were 1,386 wolves in Montana, Idaho, Washington and Oregon. That number represents a 3.2 percent increase over the previous year, even after accounting for the recreational hunts. It was a much smaller rate of population growth than previous years, but the population grew nonetheless. And it was the first year that breeding pairs were officially recognized by the US Fish and Wildlife Service in Washington and Oregon.

And how did the hunters do? In 2009, they killed 72 wolves in Montana and 134 in Idaho, or about 9 percent of the overall wolf population. Central Idaho’s rugged and inaccessible terrain proved so difficult for hunters that the state extended the season into the first few months of 2010. When it closed, hunters had shot a total of 188 wolves, which was short of the state’s target of 220.

But hunting wasn’t quite as lethal to wolves last year as lack of habitat and policies that protect livestock. Wolves have pretty much saturated the best habitat in high-elevation public forests in Idaho and Montana. That means they’re expanding their range and getting into more conflicts with the cattle, sheep, dogs, llamas and goats that inhabit more domesticated territory. In 2009, there were 944 confirmed domestic animal kills by wolf packs in the three core recovery areas, a jump of more than 50 percent from 2008, an increase that was mainly due to a taste for sheep.

But hunting wasn’t quite as lethal to wolves last year as lack of habitat and policies that protect livestock. Wolves have pretty much saturated the best habitat in high-elevation public forests in Idaho and Montana. That means they’re expanding their range and getting into more conflicts with the cattle, sheep, dogs, llamas and goats that inhabit more domesticated territory. In 2009, there were 944 confirmed domestic animal kills by wolf packs in the three core recovery areas, a jump of more than 50 percent from 2008, an increase that was mainly due to a taste for sheep.

More domestic animal kills means more wolves being killed for messing with livestock, which has been a longstanding condition of wolf reintroduction. In 2009, for instance, 240 wolves were legally killed by property owners or government agents in Idaho, Montana and Oregon to protect livestock—more than the sport hunts in those states. (In addition, as in most years, some wolves were also killed illegally, got run over by cars, or died under circumstances that couldn’t be explained.)

“They get in trouble and we end up killing them,” said US Fish and Wildlife Wolf Recovery Coordinator Ed Bangs. “The wolf population still grew last year, but they’ve filled up all the good habitat, so conflicts were a lot higher than normal and there was a lot more damage than usual. But the populations are still doing great.”

Not everyone agrees with Bangs’ interpretation.

Lawsuit Still Pending

A coalition of 13 conservation groups is challenging the decision to remove the gray wolf from the Endangered Species list in much of its Northwest range, which turned over management to the states (except in Wyoming, where wolves are still under federal protection.)

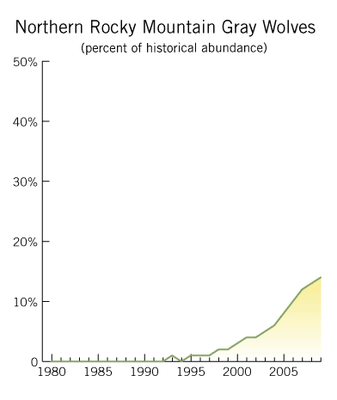

Although the wolves have far exceeded federal recovery goals, they still inhabit just a fraction of their historic range in Montana and Idaho:

The conservation groups argue that the wolf hunts can disrupt family bonds, leave pups to starve, and interfere with migration corridors. But their main worry is that the Rocky Mountain states – where anti-wolf sentiment runs high in some quarters – will just keep killing wolves.

The endangered species de-listing deal that the federal government arranged with Idaho and Montana would allow the feds to step in and review their programs if the wolf population in any of the states falls below 150 for three consecutive years, or if there’s a “change in state law or management objectives that would significantly increase the threat to the wolf population.”

Jenny Harbine, an Earthjustice attorney representing the conservation groups, argues that by the time wolf populations dropped that precipitously, even if the federal government initiated a review it might already be too late for the wolves. She said the groups are looking for a wolf management plan that’s based on enforceable standards rather than political winds.

“The states have not yet aggressively tried to reduce down to that minimum number, but nothing in state or federal law would prevent them from getting to that,” Harbine said. “Montana is doing okay now, but what if they all of a sudden decided to shoot down all but 100 wolves? Could we go to court to stop it? Probably not.”

Habitat Constraints

Bangs, of the US Fish and Wildlife Service, says Montana intends to manage its wolves at a population of around 400 and Idaho at 520. If the states dramatically revise those numbers downward, he said, that would be a trigger for the feds to take action.

One big reason wolf population growth is declin

ing is the fact that they don’t coexist peacefully as they venture into less desirable territory, according to Bangs. Packs can do well in huge blocks of mountainous public forests or rangeland where there’s plenty of deer and elk and moose. They tend not to persist in more fragmented mountain territory surrounded by open agricultural lands, where there’s too much livestock and they’re too susceptible to illegal killing.

While it’s true that wolves are expanding their range into Washington and Oregon, Bangs isn’t sure how fast their numbers will increase there. There’s plenty of large wilderness areas, he said, but a lot of rock and ice. “Wolves need something to eat” said Bangs. “I think the prediction for Oregon and Washington is going to be tough sledding.”

Update: Montana is now seeking to more than double, and possibly triple, the number of wolves that can be killed in legal hunts later this year, and wolves in Idaho could face higher hunting quotas too, according to an AP story by Matt Brown.

This post is part of Sightline’s Cascadia Scorecard project, monitoring regional trends in sustainability.

Statistics come from the Rocky Mountain Wolf Recovery 2009 Interagency Annual Report.

Wolf photo courtesy of Flickr user sometimesong under a Creative Commons license.

Sheep photo courtesy of Flickr user mrbendy under a Creative Commons license.

TLM

According to the link in this story the wolf count at the end of 2009 was 1687 – not 1386. As to the claim that they “inhabit just a fraction of their historic range in Montana and Idaho” the map below will show that they do in fact inhabit quite a bit the area. Towns and cities are not good habitat. Prime habitat as Mr. Bang’s said is already saturated.http://fwpiis.mt.gov/content/getItem.aspx?id=42232

Eric de Place

TLM,For the purposes of Sightline’s Cascadia Scorecard indicators project—of which this post is a part—we monitor the wolf populations of Idaho, Montana, Oregon, and Washington, but we exclude Wyoming (which we don’t deem to be in the Pacific Northwest). That, I think, accounts for the difference in the population count.Towns and cities are not good habitat for wolves, indeed, and that’s precisely the problem. A large portion of wolves’ historic range has been converted into settled, even urban, landscapes, and much has been converted to farming and ranching. As a result, prime wolf habitat is now only a fraction of what it once was.

Georgie Bright Kunkel

Wolves have been misunderstood and have suffered considerableharm because of it. There are wonderful books written bypeople who understand wolves and have spent their lives protecting them. I even have a wolf T shirt to celebrate their existence in our world.But we can’t protect everything that is alive. Taking antibioticskills what we call germs and even Albert Schweitzer killed the germs in his operating room even though he preached about the sanctity of all life on earth. There is no perfection when animal needs must bemet. Just to realize that all living things on earth are intertwined ina web of life that we can’t extricate ourselves from at least makes us more sensitive to senseless killing.Trillions of dollars spent on senseless warring is certainly anathema.

Barbara C

It’s not quite fair to lump Washington into this count of total wolves. At present, there are only 2 confirmed pack of 6-7 individuals each, and plenty of habitat. For WA, in fact, hunting IS the issue, since poaching by a Methow man killed at least one if not more of the first pack’s pups (don’t get me started on what an ass this man must be). I am not a fan of sporthunting at all, in fact I find it reprehensible, but I can understand the need for balance, and wolves are highly adaptable. They are also pretty shy, though, and learn quickly the meaning of Man and his gun, so I wonder if there isn’t a balance to be found between wanting every wolf eradicated and keeping people and their livestock safe. First and foremost would be to protect big areas from infringement by development—this is good for nature AND people, who benefit from wild habitat in so many ways (clean air, water, exercise, sanity!, etc) Do we really need vacation home ranchettes all over the west? They produce no usable goods (unlike keeping lands in big ranches with conservation easements and non-lethal predator management). They fragment the links between increasingly isolated patches of habitat, and they make it almost certain that wildlife interactions will lead to the culling of predators that are vital to the ecosystem.

Red Dog

THE WRONG WOLF WAS INTRODUCED PEOPLE!! DONT FORGET THE FACTS!YOU ALL HAVE BEEN BLINDSIDED BY A QUIGMIRE OF UNSCIENTIFIC MISGUIDED BUREAUCRATIC CALLOW AND ERRANT SUGGESTIONS.THE TIMBER WOLF IS THE NATIVE SPECIES TO THE NORTHWEST,FOR GOD SAKES EDUCATE YOURSELVES BEFORE YOU START PASSING JUDGMENT ON THIS TOPIC,FOR IT IS THE MAIN TOPIC FOR THE LAWSUIT COMING SOON(mid summer)THE CANADIAN GREY WOLF IS NOT INDANGERED BY ANY MEANS THERE ARE OVER 75,000 IN ALASKA AND CANADA,THE YUCON TERRITORIES ARE FULL OF THEM.THE DEFENDERS CLAIM THEY DID A PUBLIC SURVEY;CLAIM 72% OF THE PUBLIC WANTED WOLVES IN THE WILD.THAT IS SO FAR FROM THE TRUTH, THEY ALL HAVE TO BE DEMOCRATS WOULDENT YOU THINK?THIS CASE HAS FRAUD WRITTEN ALL OVER IT;THE COLLUDED SCIENCE,THE MANY ACCOMPLICES TO WHOM HAVE PROFITED FOR THIS ILLEGLE MANUVER WILL MOST CERTAINLEY BE REWARDED WITH A SENTENCE OF SORTS.I HATE TO THINK THAT WITH A GRANT OF TAX PAYERS MONEY, THAT GROUPS CAN PRODUCE SUCH A PROFOUND IMPACT ON WILDLIFE AND CLAIM NO RESPONSIBILITY FOR THE BILLIONS OF DOLLARS IN REVENUE THESE STATES HAVE LOST,I BELIVE THERE IS ENOUGH EVIDENCE TO START LEGAL LANGUAGE TO AN INQUIREY AS TO WHO HAS BEEN BOUGHT BY THESE GROUPS.GO BACK TO 1992 AND CHECK EVERYONES BANK ACCOUNTS,ALL THAT WERE INVOLVED I DO BELIVE YOU THEN WOULD START TO SEE THE TRUTH BEHIND THIS PROFLIGATED PRIVILEGE THAT THESE GROUPS HAVE PROMOTED WITHIN.GET A REAL JOB STOP STEALING TAX PAYERS MONEY! 73% OF THE PUBLIC AGREES

Kadah

“Wolves have been misunderstood and have suffered considerable harm because of it. There are wonderful books written by people who understand wolves and have spent their lives protecting them.”I understand wolves perfectly. They are apex predators that kill indiscriminately. They multiply like rabbits and push ungulate herds into Predation Pit status. Then they turn to killing livestock and pets. When it comes to humans, they prefer killing children and women.They carry 50 some diseases that are transferable to humans and livestock, including hydatid disease which is, in most cases, fatal to humans.The Canadian Gray Wolf is not indigenous to the PNW, nor the the NRM DPS. However, since being introduced as an “experimental population” in the NRM DPS they have caused the native Timber Wolf to become extinct. THE CGW is directly responsible for the decimation of the ungulate herds in Montana and Idaho. The CGW is responsible for spreading, over the PNW landscape, the Echinococcus granulosus tapeworm eggs that cause hydatid disease.Yeah, I understand wolves. Those pushing the return of the wolves are using them to push people off the land and into ecospheres where they will not be allowed to set foot in the wilderness area (defined as any land outside the ecospheres); all this in pursuit of an ungodly concept of nirvana.Are these people insane? Yes, they are insane. They are mentally insane. And they will only succeed if we allow them to.

JimmyZ

And these morons insist that the Smallest, Most human populated per square mile state west of the Mississippi can carry 15 breeding pairs. Let’s turn some loose in Point Defiance,Lincoln and Discovery parks and let them see reality, since this is their(wolf huggers) native habitat.

splevin

I disagree, look at that

http://www.greatfallstribune.com/story/outdoors/2014/11/26/wolf-pack-size-determines-type-prey/19557839/