“Buy one, Daddy!” That’s what my daughter Kathryn said after her recent ride behind Daily Score reader Jay Morrison on his all-electric scooter. Jay’s Vectrix captured her fifteen-year-old heart. Just seeing it roll up in front of the house sent her scurrying to her closet for her most Italian-looking scarf, which then fluttered in the breeze as she toured the neighborhood. She rhapsodized about being picked up from soccer practice in such style. (Apparently, being picked up on my tandem is déclassé.)

“Buy one, Daddy!” That’s what my daughter Kathryn said after her recent ride behind Daily Score reader Jay Morrison on his all-electric scooter. Jay’s Vectrix captured her fifteen-year-old heart. Just seeing it roll up in front of the house sent her scurrying to her closet for her most Italian-looking scarf, which then fluttered in the breeze as she toured the neighborhood. She rhapsodized about being picked up from soccer practice in such style. (Apparently, being picked up on my tandem is déclassé.)

Car-less I remain, but as my kids’ peak soccer season (and peak Zip-car bills) overtake me, I’ve been thinking about motor scooters. Apparently, I’m not alone: motor scooters are selling like never before in the Northwest. In fact, last year and this year to date, two-wheeler sales (including both scooters and motorcycles) are outpacing sales of passenger cars even in auto-friendly Boise and surrounding Ada County, Idaho.

For short, in-city trips that don’t require traveling at high speeds—like, say, delivering someone to soccer practice four miles from home over city streets, a motor scooter seems like a useful addition to my quiver of personal urban transportation options: foot, bicycle, public transit, taxi, and Zipcar. A scooter seems especially attractive for a newly single dad of a fifteen-year-old daughter. Her younger brother and I are usually happy to cycle just about anywhere, but she is more prone to respond to a suggestion that she don her bike helmet and pedal where she wants to go with, “Hello?! Teenage girl! Hair!!!” (Releasing her glowing tresses from of a motorcycle helmet, apparently, would be a style plus, not a minus.)

Gasoline-powered motor scooters are old and familiar technology. They carry tens of millions of people in China and India, as they did in southern Europe in the post-war years. In developing countries, motor scooters cost as little as $300 apiece, which helps explain why an estimated one-third of the world’s motorized vehicles are two-wheelers.

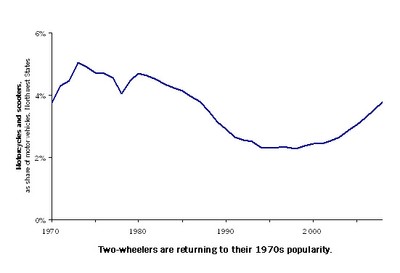

Here in Cascadia, of course, motor scooters and motorcycles make up less 4 percent of motor vehicles (and a smaller share of miles driven). Still, their numbers appear to be rising quickly, as this figure shows. As a share of all vehicles, they are heading back into the range of their peak popularity—the 1970s. (In fact, if my eyes don’t deceive me, two-wheelers numbers move up and down with the price of gasoline.) (I assembled this chart from Federal Highway Administration information, but I guesstimated the 2007 and 2008 figures based on press reports I’ve seen about surging sales of scooters and motorcycles.

Motor-scooter Pros: Motor scooters are impressively fuel efficient. Some gasoline-powered ones can go more than 100 miles per gallon. Their carbon footprints, while larger than bicycles’, are small. They’re affordable: imported Chinese models cost less than $1,000 online (although some of these models don’t comply with air-quality rules in North America), and even the category-leading brands such as Vespa sell some of their models for under $4,000.

Motor-scooter Cons: As you probably know, motorized two-wheelers are more dangerous for their passengers than just about any other form of personal transportation. Lots more dangerous. I’d only want to ride one slowly and away from heavy traffic—sort of like I ride my bicycle.

What you may not know is that motor scooters, like motorcycles, are dramatically worse for local air quality than passenger cars, pick-ups, and SUVs. The problem is that pollution-control equipment is hard to fit on a small vehicle. The Idaho Statesman examined the issue in its August 8 article “Is your scooter a polluter?” (No link; it’s behind the Statesman’s pay wall.)

“The cleanest scooter is still dirtier than a car,” said John Swanton, air pollution specialist with the California Air Resources Board.

. . .

Some motorcycles emit as much hydrocarbon in 10 miles as a car driven 850 miles, according to Environmental Protection Agency studies.

Car engines use much more fuel and create more pollution than motorcycle engines, but sophisticated emission-control devices prevent much of a car’s emissions from getting into the air, said Wayne Elson, environmental protection specialist with the EPA’s Seattle office.

When it comes to reducing fuel consumption and improving global climate conditions, a motorcycle or scooter is still the better choice, Swanton said.

But when it comes to reducing smog and improving local air quality, “the Hummer is better than a small scooter because it has more sophisticated emission controls,” he said. “Its emissions are pretty low relative to a motorcycle.”

Motorcycles and scooters that meet EPA emission standards are still more polluting than cars because the federal emission standards are more lenient for motorcycles.

The maximum emission standard for motorcycle hydrocarbon and nitrogen oxide is 2.25 grams per mile, compared with .098 for cars, meaning a motorcycle can emit 23 times more ozone-forming pollutants as a car does and still meet EPA standards. The carbon monoxide standard for motorcycles is about six times higher than a car’s standard.

EPA’s air quality rules for new motorcycles and motor scooters are scheduled to tighten in 2010 (pdf), but they’ll remain far laxer than are the rules for four-wheelers (pdf, see page 3).

That’s why I don’t so much want a motor scooter. For rural riding, where air quality isn’t an issue, a scooter might be fine. But for city travel? I don’t want the karma of six or twenty-three cars’ worth of hydrocarbons, nitrogen oxides, or carbon monoxide.

Nope, I don’t want a gasoline-powered motor scooter. Electric ones might be a different story, which is why I invited Jay to bring his bike over and show it off.

Electric motor scooters cause no degradation of local air. Because of their smaller mass, their range and recharge speeds are much better than those of electric cars, which I worried about while test-driving a plug-in hybrid last fall.

Electric scooters come in a variety of sizes and designs, but the Vectrix is one that’s pow

erful enough to carry two. It can run at highway speeds (faster than I’d want to go) and has a 50-mile range between charges. Video here and here. (Hat tip to Jay.)

It recharges fully in three hours, using only about 40 cents’ worth of electricity in the process. That means fueling the Vectrix costs about a penny a mile.

The electric scooter is also a big winner for the climate, with emissions about a tenth as great as driving a Prius, and about a thirtieth as great as driving an SUV. I estimate (calculations below) that a Vectrix operating in Cascadia generates about 1/20th of a pound of CO2 per mile—all of it coming from the power plants that charge its batteries. Looking at Sightline’s chart of greenhouse impacts of different vehicles, I see that the Vectrix has a bigger carbon footprint than a bicycle. But it’s still exceptionally clean.

Of course, electric scooters have disadvantages as well. Like all electric vehicles, their range is a fraction of liquid-fueled vehicles’ ranges. Three hours is a lot longer to refuel than the minute or so it takes to refill the tank of a gasoline scooter. Unlike gas scooters, electric ones employ new, glitch-prone technology, as you can see by skimming this website where owners of Vectrixes exchange technical tips. Last but not least, electric scooters cost more up front: about $8,800 for a new Vectrix, plus taxes and registration (plus helmets and protective clothing). The cost per mile, if you believe Vectrix’s own numbers, is attractive: it’s cheaper than a gas scooter overall.

Yep, if I had that kind of money lying around—or access to an innovative energy-conservation loan—I might just buy one.

Note on calculations: Vectrix has published its own assessment of its air quality and climate impacts (pdf). To compare the Vectrix in greenhouse gas emissions per mile in Cascadia, however, I did my own math. Vectrix’s battery capacity is rated at 3.7kWh and its range is rated at 50 miles, which yields an energy efficiency of .074 kWh/mile. At the Northwest’s power system’s marginal CO2 production rate of 0.7 pounds per kWh, the Vectrix generates .052 pounds CO2 per mile.

James

Great review Alan. I didn’t even see you taking notes. All we need to do is get you a motorcycle jacket and you are ready to ride !!!

Matt the Engineer

Hmmm… The comparison seems too simplistic to me. It doesn’t look like they’ve even separated 2-stroke engines from 4-stroke engines, let alone compared those that qualify for California’s nice CARB standards.Here‘s information on my scooter (sadly, they stopped production in 2006). The manufacturer claims only 0.43 grams of hydrocarbons per mile. Actually, they also claim that cars emit 2.8 grams per mile and cite EPA data from 2000 to back it up. That’s quite a difference from the article’s claim of 0.098.

Matt the Engineer

Because the numbers really didn’t match between the article above and the Bajaj study, I ran a quick calculation myself. According to EPA’s website, a 2008 Honda Civic sold in WA meets the qualification of CARB’s LEV II standard (low emitting vehicle). Going to the CARB standard, this means it has a maximum of 1.9 grams per brake horsepower hour, which works out to around 1.7 grams per mile (oh how I wish EPA would just list hydrocarbons per gallon). This implies that the Bajaj website is right, since I’m sure a modern Civic is much cleaner than the average car on the road.

Steve

How’s the noise level on electric scooters? As one who likes to talk to friends while walking down streets, I *hate* the acceleration noise of motor scooters.

Alan Durning

Matt the Engineer,I had a hard time finding any actual air pollutant emissions data from actual motor scooters, so thanks for your link. Your command of “brake horsepower hours” exceeds my own. Would you do me a favor and review the EPA links I included? I had the Puget Sound Clean Air Agency also review the Idaho Statesman article. They thought it was basically right.I’d love to learn that gas motor scooters are cleaner than the Statesman, EPA, and Puget Sound Clean Air says.Steve,The Vectrix was very, very quiet. All I could hear was the sound track of Road Warrior, and I’m pretty sure that was just in my mind. 😉

Matt the Engineer

The article could certainly be “right”. I’m just arguing that it’s simplistic. The difference between a 2-stroke and a 4-stroke engine is the difference between a leaf blower and, well, a modern motorcycle. By considering the worst case or even the average case, you’re letting the cheap 2-strokes drag down all of the high performance vehicles.Reviewing the two PDFs, it looks like the EPA has removed 2-stroke motorcycles and scooters from the highways a good 20 years ago. In 2006 they tightened up regulations further, down from 12.8 g/mile to 1.6 g/mile for all but heavy weight motorcycles (which are restricted further). However, I believe in most states (including WA), 2-stroke scooters make it on the road by calling themselves mopeds (this also lets you ride one without a motorcycle license).Of course, these are the maximum emissions allowed, and therefore it’s not a terribly fair comparison. These days even several 50cc “mopeds” have 4-stroke engines and comply with CARB standards.This all being said, I do agree that electric scooters are the future. But regulating mopeds (and leaf blowers, for that matter) wouldn’t be a bad idea. Above all, I’d love to see hard measured data about 4-stroke 2-wheeled vehicle emissions – something I haven’t been able to find.

alan

Thanks, Matt the Engineer,I heartily agree about the desire for actual measurements.

Barry

Our family has been riding our electric bike just about every day for a couple years now and really enjoying it. I recommend it as an affordable alternative to electric scooters for many people. While an e-bike doesn’t do everything an electric scooter does, it does have many advantages:* much less expensive (ours was $700)* quick recharge time* much fewer resources go into making one* if it runs out of power, you are on a bike and can still ride* light enough to lift onto, and carry on, a car’s bike rack* less energy used per mile* simple to work on* more exercise, but not so much you sweatDid i mention fun? E-bikes i’ve come across aren’t self-propelled…instead they augment your own power quite a bit. Most adults i know who have tried one come back with a big smile saying something like “wow, i felt 19 years old again.” They have been increasingly popular in last few years in our hilly rural area…and a number of people now commute daily with them.I was having a very hard time kicking the drive-solo car habit because of our hills and weather. The e-bike changed all that instantly. Now we never drive solo unless we have to go long distances or carry a lot of stuff, which is rarely.

Alan Durning

Barry,Good points. I tested out some electric bikes more than a year ago. I wasn’t much taken with them personally, but that’s because I so love regular cycling (hills and all). Electric-assisted bicycles definitely have a big place in our transportation future, for all the reasons you mention.But I can’t take my daughter to soccer practice on one, so they serve a different purpose.

James

Alan, to go with your motorcycle jacket, we also need to get you a tattoo. Perhaps “Soccer Dad” and something with a Harley theme.http://www.temptatts4u.com/Harley.htm

Alan Durning

James,Why do you assume I don’t already have a tattoo? Or several? ; )I mentioned in today’s post on Living Within Our Means that I spent two weeks at Stanford b-school in 2006. One marketing lecturer there pointed out that the best branding efforts in the world turn customers into promoters. She cited Harley Davidson as a case in point: some hog lovers tattoo the brand on their bodies.That’s when I stood up in the lecture hall, ripped open my shirt, and displayed the Sightline tattoo that blankets my upper back.(Or maybe that last part was only in my imagination.)Anyway, we’ll happily provide high-resolution jpegs of our branding for anyone (else?) who’s ready for a Sightline tat. We’ll even email it directly to your favorite body artist.Any takers?

MVP

er… maybe if Sightline’s logo weren’t so, shall we say, phallic looking, then maybe I’d consider it…(never thought I’d say that out loud, so let’s just keep that between us! 🙂

Doug

I have an electric scooter and I love mine. I have only used $8 of gas in my car since I got the scooter. Mine is smaller, slower and cheaper $1500, but works great.

TurboDave

Alan,While federal air quality standards are not high for two wheeled vehicles, it is worth noting that it is possible to ride a motorcycle that delivers good fuel economy and good emission controls. I ride a single cylinder 650cc BMW that meets Euro 3 emissions standards and that delivers an average of 64 MPG on 87 octane. I’m not looking this up to verify it, but my recollection is that Euro 3 is comparable to 2008 CA auto standards, which will be 2010 U.S. standards. This bike costs more than scooters, but with fuel injection and a catalytic converter – this is as good as it gets with gasoline right now (3 times the mileage of my car, and much cleaner at the pipe).

Alan Durning

I’ve never looked at Sightline’s logo that way before. Hmm.What make of electric scooter costs only $1,500?Turbodave,Meeting the CA new-car clean-air standard is pretty impressive for a two-wheeler. I’d be interested in confirmation if you can find it.Still frustrated by the absence of actual emissions measurements for operating vehicles.

MVP

Alan,I think my interpretation is a hang-over from an interesting Anthropology class that I had in college.Plus, in a Marketing class, we were taught to never create a logo that could be misinterpreted in any way, if we want to have the *BEST* brand associations, subliminally and otherwise.Ah, higher education. Really opens your eyes!:-)

TurboDave

Alan, Here is an excerpt from an article on Motorcycle-USA.com on motorcycle emission standards:”In the late ’70s the EPA enacted the first federal emissions requirements for on-highway motorcycles, with compliance required for the 1980 model year. These initial regulations remained unchanged until December of 2003, when the EPA announced its plan to establish new requirements modeled after those implemented by America’s most populous state – California.The Golden State’s new restrictions were set up in a two-tiered phase, with the first wave of limits going into effect in 2004 and a second wave kicking in for 2008. The federal EPA mimics California’s standards but two years behind, with Tier 1 beginning in 2006 and Tier 2 taking effect in 2010. The hard numbers equate to Tier 1 limits of a combined 1.4 g/km of HC and NOx with 12 g/km of CO. Tier 2 raises the bar to 0.8 g/km of HC+NOx with the same 12 g/km of CO.These new U.S. standards mirror toughened requirements in the European Union, which has also employed a tiered phase-in known as Euro II and Euro III. A direct numeric comparison between the EPA and EU standards is problematic because the two organizations use different testing cycles to collect emissions output (although the EPA has expressed interest in one day adopting the new World Motorcycle Test Cycle, which is used by the latest EU regulations).EPA documentation describes the new Euro III standards for HC and NOx emissions as “roughly comparable to and perhaps somewhat more stringent” than the corresponding EPA Tier 2 standards of 2010. The most notable difference between the EU and U.S. standards being the giant gulf in CO restrictions, with the EPA not budging from its original 1980 threshold of 12.0 g/km, while Euro III imposes a far more ambitious 2.0 g/km limit. The discrepancy is not as dramatic as it sounds, as typical U.S. motorcycles already far exceed the 12.0 marker by default due to the comparable HC+NOx restrictions.On-Highway Motorcycle Emission Standards for EPA and EU HC (g/km) NOx (g/km) CO (g/km)1980 EPA Limits 5.0 NA 12.02006 – Tier 1 1.4 (HC+NOX) 12.02010 – Tier 2 0.8 (HC+NOX) 12.0Euro II (2004) 1.0 0.3 5.5Euro III (2007) 0.3 0.15 2.0Distilling the EPA’s On-highway restrictions down to their basic levels, the original 1980 laws eliminated on-highway two-strokes. The current two-tiered upgrades will force most motorcycles into the catalytic converter era.”All BMW motorcycles use catalytic converters (reportedly made of recyclable materials) and meet Euro-3 standards. You can check out the online brochures at bmwmotorcycles.com. Other European motorcycles such as Ducati and Moto Guzzi are the same. We get the same bikes in the U.S. as it is not worth it to these low volume producers to make “dirty” bikes for the U.S. Japanese bikes sold in Europe do have to meet Euro 3 standards; the U.S. does not get the clean bikes. I found two other articles like yours on 2 wheeler emissions. There were similar comments to mine about European bikes. It seems authors do not speak to people knowledgeable about motorcycles or scooters. Thanks, Dave

TurboDave

Link to motorcycle emissions article:http://www.motorcycle-usa.com/Article_Page.aspx?ArticleID=4352=1Link to BMW Brochure – see page 6 for reference to a 3-way catalytic converter and compliance with Euro 3 emissions standard:http://www.bmwmotorcycles.com/pdfs/f650gs_brochure.pdfIn addition to BMW, Moto Guzzi and Ducati motorcycles – the Vespas are scooters which are also compliant with European standards. In spite of low standards in the U.S., there are products which exceed those lousy standards. Cheap scooters from Asia and two-stroke scooters – not good!! AND, I am very interested in electric scooters and motorcycles (which Honda may be considering).Thanks,Dave

Callie Jordan

Alan, I can’t answer for Doug but I found a brand-new electric scooter for supposedly less than $1500, called the eGO. (Turns out I even know someone who has one, since she sent her photo in for the company website.)That price was from a review on ElectricScooterWorld. The company website’s list of US dealers includes two in Port Townsend, one in Spokane, and http://www.usagreencars.com/“>one in Olympia. It looks, however, like you’d be hard-pressed to get two people on it (although it was tested with a 225 lb rider). So probably still not your soccer-transport answer.I got an electric bicycle, because my commute is one mile straight up. Contrary to popular opinion, you can’t pedal them if you lose power. (They don’t even coast on level ground! Mine weighed 70 lb.) Callie

Barry

There are many kinds of e-bikes. Some, as Callie testifies, don’t pedal well without power while others do. The most popular in our area by far is by Bionx and it pedals just as well without power as a normal bike. It also has Lithium battery and is much, much lighter than 70lbs. I don’t have this model but many friends do and all love it. Best to shop around and try several kinds before you buy.Alan is right you can’t haul a larger child on an e-bike. However i do know families that attach a trail-a-bike extension onto their electric bike and use this as their primary kid-mover for younger kids. As kids get bigger the only e-bike kid-mover option i know is to get a second e-bike for the child to ride along with you. I also know families that do this.E-bikes aren’t for everyone as Alan rightly points out…but with creativity and research this simple, very low impact end of powered transport can do a surprising amount.

Alan Durning

CNN recently profiled some other electric scooters

MVP

Indeed! Combine that creative and noble notion (cnn) with this one, and you’ve got a truly lovely idea with unlimited mileage potential! 🙂

yamaha raptor 250r

Scooters offer an excellent alternative to cars while running around town. They are easier to park and maneuver, get better gas mileage and then there is the fun factor. A good size to start with is a 50cc engine. If you willing to buy a used Japanese scooter, these can be had for less than $2k. The other alternative is a Chinese scooter. This not a good idea unless you buy from a shop and not the Internet. If you buy from a shop, there will be someone to get parts and repairs from. If you buy from the Internet these people have no reason and no resources to help you.

Percy Fox

A couple of updated notes: Now, in 2011, some excellent Italian-made gasoline-powered scooters are available for under $2000. (Four-stroke Aprilia comes to mind.) However, you’d pay about $4000 for very similar performance specs for a comparable electric scooter. You can get a scooter style e-bike for as low as $800. (22mph limit)Something I wondered about the EPA car-vs-scooter standards was: as long as the vehicle is not exceeding the standard, what’s the problem? I (naively?) trust that the government has set the “standard” at a safe level. If the scooter meets the scooter standard… hurrah.What’s never been addressed is that Americans love our cars. It’s not just a vehicle, it’s a family member or a hobby. I’m one of the rare ones who thinks of my car just as a tool, like a blender.

sam deal

i love scooters but im disabled and cant afford to buy one straight out

www.youtube.com

It iss almost impossible to put into words the inner intensity that an Indigo feels, buut one way is that it feels like megawtts of burning energy vascillating beetween “Can someone share this joy with me. There will be particular recommendations you will have to follow and it will be feasible for you to get in touch with individuals who want to shell out you hard cash for your car. Another thing is that it can be quite a hassle to drive a manual in the city, as you could get tired easily by the fact that you have to press and depress the clutch constantly.

vidente buena y economica de verdad

Hi there, yeah this article is actually good and I have learned lot of

thinfs from it concerning blogging. thanks.