There were two fascinating tidbits in Wednesday’s Sightline Daily news roundup from our pals at the Stockholm Environment Institute. And both of them demonstrate how math can provide a useful perspective on sustainability challenges.

The first article compared the climate impacts of food composting with not wasting food in the first place. Unsurprisingly, the research shows that it’s better to eat food before it spoils than to let it spoil and then compost it. But how much better? According to the Oregonian, SEI’s calculations show that “not wasting food saves 30 times more than the emissions that come from food disposal.” [Wonk alert — as commenter Dave correctly points out below, that Oregonian quote doesn’t accurately represent SEI’s research. Dave’s best estimate from SEI’s sources is that reducing food waste by 5-50% has somewhere between 3 and 113 times the GHG reduction potential as composting. My mid-point estimate (not Dave’s) from Dave’s figures is that reducing food waste has about 25 times as much GHG-reduction potential as composting — but that’s just a rough estimate, and will obviously depend on the specifics.]

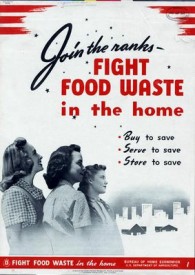

So if we’re concerned about climate change, we should probably concentrate more on reducing food waste than on getting people to compost their food scraps. That’s not to say that composting programs aren’t a good idea—they are! Yet to me, the numbers that SEI ran reveal a curious, deep-held bias in public policy. We pay an awful lot of attention to how we throw our waste away—we run major public campaigns to promote recycling and stop litter. But we don’t make nearly enough effort to keep things out of the waste stream in the first place.

The second article covered SEI’s comprehensive inventory of greenhouse gas emissions in Oregon—including out-of-state emissions from the goods and services that Oregon residents consume. As you might guess, the study found that locally-produced goods have a lower carbon footprint—but not for the reasons you’d think. According to David Allaway of the the Oregon DEQ:

It’s not because of freight – everyone thinks it’s because of freight. The emissions from freight are surprisingly small. It’s because production here in the United States tends to be cleaner and use lower carbon-fuel mixes than production in the countries that we tend to import a lot of products from. [Emphasis added]

That matches with my intuitions—but that’s only because I work with these sorts of numbers an awful lot. As it turns out, moving people takes a lot of energy: we like a lot of space, and we’ll often move a ton of vehicle per person when we take long trips. But shipping goods takes less energy than you might imagine: you can pack an awful lot of stuff into a shipping container, and rail and boats are fairly efficient ways to move things around.

In both cases—food waste and long-distance freight—the math reveals a distinctly human foible. When we think about a long and complicated process, the last few steps loom large in our thoughts. For food, we concentrate on shopping bags and food scraps; for freight, we think about how the goods got to the store.

Sometimes the mental shortcut works. The biggest climate impact of your car, for example, really is what comes out of the tailpipe; vehicle manufacturing is still important, but not nearly as much as driving. But for many other issues, you simply can’t count on your intuitions. Like it or not, if we want to make sure we’re concentrating our efforts where they can do the most good, someone actually has to do the math.

Ann Vileisis

Thanks for the very interesting analysis Clark.

When you stop to think about it, it makes total sense that the carbon footprint of food waste would be so high!

Though I suppose a lot of the food waste you are talking about is from restaurants and institutions rather than home kitchens, I am always surprised when people confess that they have food rotting in the fridge.

It makes me think of my great grandmother. She had a reputation of being able to cook “something from nothing.” She could throw together leftover bones and bits of vegetables to create fabulous soups and pot pies. She never let anything go to waste. Her frugality was borne from a personal heritage of war-time privation (WWII in eastern Europe), but it also sparked tremendous creativity.

We need more of this little-appreciated, every-day sort of genius to tackle the improbably consequential problem of food waste.

Clark Williams-Derry

I’m certainly not one to point fingers. I have the reputation in my house as the food vacuum cleaner — I try to eat up the leftovers that the kids won’t. Still, I’m sure if you checked my fridge you’d find some food that was well past its use-by date. And a friend jokingly refers to the “crisper” at the bottom of the fridge as the “rotter.”

Daniel Henderson

So do we! But that’s mostly because we forget that there’s food in the crisper.

Anyway, great article as always.

dniall

What’s for dinner, dear? Umm…tea bag and banana peel stew!

Meredith

Great article, Clark. Just curious, since I assume you’re read the SEI report and I have not (yet): why are the emissions from wasting food 30 times greater than composting it?! I imagine it is b/c all of the carbon that goes in to producing, transporting, refrigerating, cooking the food is just wasted carbon if the food goes uneaten. And then composting the uneaten food (vs. rotting in a landfill) might just save a little carbon at the end?

Clark Williams-Derry

I haven’t yet. But yes, producing, transporting, processing, storing, selling, and cooking food takes a lot of energy. And there’s a lot of methane and NOx produced from fertilizers, animal waste, etc. In comparison, the decision about whether to send waste to the landfill or the composting facility is, er, small potatoes.

Dave

Clark,

I’m disappointed in your “research” for this essay. The “two” articles you describe are actually based on only one report from SEI.

I read the original report, and the Oregonian author’s statement, “not wasting the food in the first place has at least 30 times the benefit when it comes to cutting global warming emissions, a new study commissioned by Oregon’s Department of Environmental Quality concludes” is a misinterpretation of SEI’s work.

What the report actually says is “the “upstream” greenhouse gas emissions associated with food consumed in Oregon are roughly 30 times higher than the emissions associated with disposal of uneaten food by consumers.” This means that the production-related emissions of food consumed in Oregon (8.9 Million Metric Tons CO2e) is 30 times greater than the disposal-related emissions (0.3 MMT CO2e). That does *not* mean that “not wasting the food” is 30 times the benefit of composting. Nowhere does the report make any assertion about the specific difference in benefit between not wasting food and how one disposes of food (i.e., composting). So the Oregonian author took a figure he saw in the report (30 times greater) and applied it incorrectly to a comparison that he wanted to make (food waste vs composting), since Portland just started municipal collection of food waste and it is therefore a big public issue right now.

I am disappointed that Sightline perpetuated the Oregonian author’s error first in its Sightline Daily and now in your essay.

Yes, math provides “a useful perspective on sustainability challenges”, but only if one uses it correctly and doesn’t misinterpret facts to support one’s expectations/biases.

Clark Williams-Derry

Let’s just quote from the report itself then:

“Food is also important because significant amounts of food are wasted. By one estimate, food waste in the US has increased from 30% ofthe available food supply in 1974 to almost 40% in recent years; in 1974, approximately 900 kcal per person per day was wasted, whereas in 2003 Americans wasted ~1,400 kcal per person per day. According to our analysis, the “upstream” greenhouse gas emissions associated with food consumed in Oregon are roughly 30 times higher than the emissions associated with disposal of uneaten food by consumers. In other words reducing the wasting of food – both by consumers and also upstream in the supply chain – can significantly reduce life-cycle greenhouse gas emissions, so long as waste is reduced at the source (by reducing excess production and/or purchasing). Managing wastes after they’re produced (composting, for example), offers a much smaller potential for greenhouse gas reductions.”

I’ll leave it to other readers to decide whether what I wrote quotes the Oregonian inaccurately, or gives a misleading interpretation of SEI’s study.

That said, I agree that the Oregonian quote doesn’t quite capture what SEI says. But I’m not sure what the right multiplier is. The relevant comparison is really emissions reductions from stopping food waste vs. emissions reductions from switching from landfill to composting disposal. SEI doesn’t address those issues directly; but it’s clear that they think that stopping food waste could have a much bigger CO2 impact than specific waste management choices.

Danny

I totally agree with Dave, and was pretty surprised by the “30 times more emissions” statement. To truly figure out the difference in carbon from eating all your food compared to composting, one would need to estimate the reduction of food purchases caused by not wasting food. On top of this food is a very heterogenous category in terms of carbon emissions. Reducing the purchases of local fruit and concentrated feeding lot beef have very different implications for carbon. A much more careful study would needs to be conducted to make the claims that this article states. Though I do agree that the a significant way to reduce emissions from food is to buy less food.

Dave

Clark, I think it’s worse than “doesn’t quite capture”. The Oregonian article is grossly misleading. He took the “30 times higher” comment about the difference between production/disposal emissions and applied it to a comparison of food waste vs compost. Not correct. At all.

My point is that SEI did not determine the multiplier, they only asserted a qualitative difference. Yet the Oregonian author made up a multiplier by seeing a number and lazily applying it incorrectly. I would love it if someone did the research to determine the actual multiplier. I tried to, but this was my best shot: In the “Interim Road Map to 2020” (Oregon Global Warming Commission, http://www.keeporegoncool.org/sites/default/files/Integrated_OGWC_Interim_Roadmap_to_2020_Oct29_11-19Additions.pdf) cited by SEI, I found projected GHG savings for “Recovering food waste municipally” (i.e., composting) of 0.01-0.04 MMTCO2e, and GHG savings from “Reducing food waste by 5-50%” of 0.12-1.13 MMTCO2e. Using the min/max of the ranges, this means the quantitative benefit of reducing food waste might be somewhere between 3 and 113 times greater than composting. So 30 might be right. But the point is, that’s not what SEI said.

But no one will need to actually calculate the multiplier now, because the “30 times” figure is out on the Internet, and now even Sightline has given it credibility. That’s my biggest concern. This will become an Internet meme/fact that others will cite (as you have), even though the source document never made the assertion.

Clark Williams-Derry

Fair enough. I don’t agree that nobody will ever see the need to calculate the number — in fact, my experience is that having a number in the public domain will prompt someone to check it — but I do agree with you about the inaccuracy of the Oregonian quote. I’ll update the post to reflect that.

Dave

Thanks, Clark. That was an overly pessimistic comment. You are certainly right that having a number in the public domain prompts someone to check it — that’s why I read the report, after all, and am now writing to you and the Oregonian. My hope is that SEI also notices the Oregonian’s faulty interpretation and does the work to calculate a more robust multiplier.

Sorry if I came on too strong initially. I meant to write to the Sightline Daily editors on Wednesday to suggest the correction to the faulty headline, but didn’t do it. When I saw this post, I knew I had better respond soon or forever hold my peace.

Clark Williams-Derry

No problem, Dave. Unfortunately, I do let this sort of criticism get to me. It makes me not want to do my work. Seriously. I care deeply about accuracy, and I quickly correct my mistakes when I make them (or inadvertently propogate them). So if you think I’m wrong about something, feel free to shoot me a quick email — we’re all about being as accurate as possible.

Cheers.

Dave

My other main point is this: composting is better than not composting. And inasmuch as the misleading Oregonian article makes composting look “lesser than” in terms of its value, that’s bad. If people generate food waste, they should compost it rather than put it in the trash.

Some other relevant points:

1) Much “food waste” is *not* potentially edible food — it is peelings and coffee grounds and eggshells, etc. That “wasting of food” cannot be reduced in any meaningful way. How does this relate to the discussion?

2) Studies on the percentage of food waste are few and far between, and are short on real data. The one SEI cited uses modeling of the amount of food produced in the US and people’s weight change since 1970 to determine how much of the food that is produced is being eaten, and therefore how much must be wasted, rather than measuring actual food waste data. I’ve seen a few other journal articles that raise doubts about the high food waste percentage figures, and whether most of the waste is in the producer side or the consumer side.

I’m not saying food waste isn’t an issue. I’m saying it’s one that needs a lot more research to get at the real magnitude and root of the problem. “Armwaving” stats like 40% of all food is wasted get people’s attention, but may have some large error bars.

Clark Williams-Derry

Agreed that composting is better than not composting. I’m not sure about the end results of focusing people’s attention on composting vs. waste. Does it make people think twice about wasting food? If so, and the 3-113 multipliers are right, perhaps that’s a good result.

I’ve found the USDA food availability database to be quite helpful in parsing out food waste. As with all data sources, a lot of it is estimated. But they’re trying to use consistent methods over time, and from my past email exchanges with them they seem serious and competent. Their best estimate is that there’s ~1200 calorie per day gap between nutrient availability and actual food consumption. Of course, that does beg the question about which kinds of calories are wasted. Are they disproportionately high-impact foods, or not? I looked, and decided that it would take more time than I had available to figure out.

dniall

I’ll have to send you guys my recipe for cabbage-butt and eggshell souffle. It’ll blow your minds!

Clark Williams-Derry

Thank you, dniall! I’d be happy to bake you a batch.