The State of Parking Mandates in Washington

Minimum parking requirements are paving over Washington, regardless of how much parking residents or businesses actually need.

Sightline Institute

Catie Gould | October 2024

Download the ReportParking matters: How parking mandates silently shape our communities

Look at just about any city’s zoning code and you’ll find a table of parking ratios, usually dating back 50 to 80 years, mandating a predetermined number of parking spaces for all new buildings—and for every new bedroom, church pew, or bowling lane. If new development built “adequate” off-street parking, the thinking went, cars and curbsides could be managed.

But one-size-fits-all mandates, determined by city planning offices, were the wrong tool for the job. Guessing at the right numbers, most jurisdictions erred on the side of excess. Beyond creating an oversupply—parking that doesn’t get used—mandating too much parking carries a raft of unintended consequences. Too much required parking outlaws the kinds of buildings that define cities’ historic walkable neighborhoods, blunts housing construction and drives up home prices and rents, and increases barriers for entrepreneurs who want to invest in their community. Instead of managing on-street parking, these regulations have locked cities into patterns of sprawling development that makes traveling without a car impossible. In short, parking mandates have silently shaped how we live and how we get around.

Mandatory parking minimums reveal a failure of centralized control over something that any homeowner or business owner knows varies from block to block. These regulations fail to see, for example, the single mom who, like 40 percent of Wenatchee households, has no need for the second parking space the government requires her to pay for in her rent. They dismiss the local entrepreneur with an idea that could light up a vacant building, if that entrepreneur were legally allowed to operate their business with 14 on-site parking spaces instead of 23. Ultimately, these mandates rob Washingtonians of their right to decide for themselves how much parking they really need.

Consequently, Washington cities have inherited a mess where housing is scarce, commercial vacancies abound, and automobile dependency is baked into legal codes. This report aims to bring these arbitrary regulations to light and show how these rules from the past still shape life today in communities across the state.

Table of Contents

- Arbitrary and excessive parking mandates in Washington State

- Methodology

- A history of guesswork

- The high cost of excess parking

- Parking mandates overestimate car ownership and undercut homebuilding

- Parking mandates are a tax on businesses

- If exceptions are the rule, the rule is flawed

- Right-sizing parking lots: Parking reform in Washington

Acknowledgements: Thank you to the many people who contributed to data collection for this report, fact checking, and editing, including Sightline staff and Tony Jordan, Joseph Alamo, Ethan Chan, and others at the Parking Reform Network. Thank you to Sam Vogt for graphic design and to David Ryder and Jake Parrish for photography.

Arbitrary and Excessive Parking Mandates in Washington State

Local laws lock communities across the Evergreen State into more pavement and sprawl, barriers to business and homebuilding, and high rents.

Sightline analyzed zoning codes in 54 jurisdictions, representing regulations for land use where three-quarters of Washingtonians live. We found that parking ratios vary widely across city and county lines, but that Washington communities consistently mandate an excess of parking that is out of sync with people’s actual car ownership and counterproductive for local homebuilding and business development.

Key findings

Mandated parking spots exceed cars Washington renters own

Fifty-eight percent of all Washington renter households own one or no cars, but in most cities and counties, it is illegal to construct a home with only one parking spot.

Six out of every ten jurisdictions surveyed require even studio apartments to supply more than one parking space per unit, while two out of ten require that studios come with two parking spaces apiece—overbuilding parking for most residents.

Mandated parking spots also outnumber the cars Washington homeowners own

One in four homeowner households in Washington have one or no cars, but nearly all jurisdictions (91 percent) require two or more off-street parking spaces for every detached home.

Four jurisdictions require three or more parking spaces for single-detached houses, though only 35 percent of homeowner households have more than two cars.

Excessive parking mandates undercut less expensive, “middle housing” home choices

Twenty-eight percent of Washington cities and counties have made parking optional for accessory dwelling units (ADUs). But only in Spokane are duplexes granted the same flexibility.

Family-friendly apartments pay a parking penalty

The more bedrooms, the more parking required. Across the state, 59 percent of localities require additional parking for larger apartments, increasing barriers for family-sized units.

Parking mandates hinder local businesses, especially in historic downtowns

The typical office or retail store in Washington is required to dedicate more space to parking than to the building itself. The most common mandate for restaurants requires three times as much space to be paved over for parking than the dining establishment itself.

Converting a former office to a retail store would require providing additional parking in most cities and counties. A restaurant would require more parking in nearly every jurisdiction.

Parking mandates vary widely between jurisdictions, but generally they exceed actual use

For the same types of businesses, places with the highest minimums require 3 to 12 times more parking spaces than their neighbors with the lowest minimums.

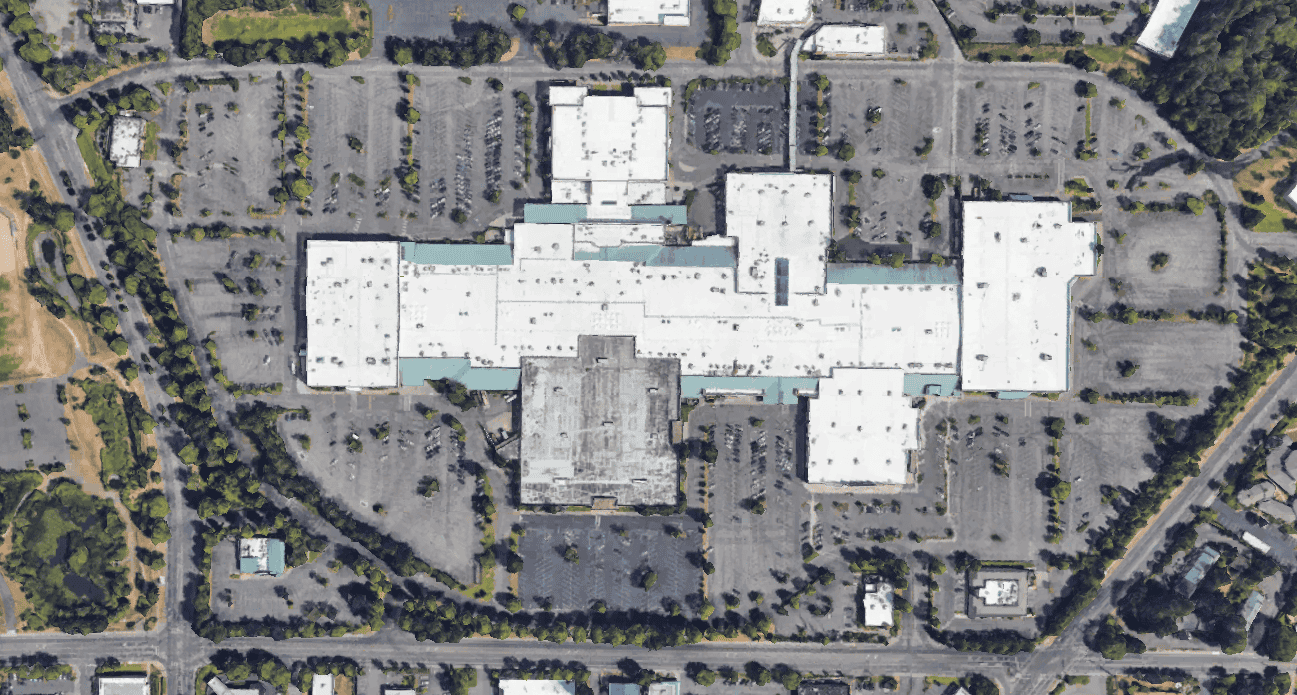

Rules prevent new buildings, even on vast, underused parking lots

Olympia’s Capital Mall can’t transform its unused parking lots into a people-oriented urban center under current zoning rules that deem it “underparked,” with 214 fewer spaces than required for a shopping center.

Methodology

For this report, researchers reviewed minimum parking requirements for key housing and commercial categories across Washington’s largest 44 cities and 10 counties. Together, these jurisdictions regulate the land that is home to 75 percent of the state’s residents.

While nearly every city has at least a handful of downtown blocks where providing parking is optional, we chose to compare the base tables that set regulations city- or countywide. These ratios are the starting point from which any reductions to required parking must work (often in percentages) and are easiest to compare across borders. For the handful of jurisdictions that had no base tables but instead set unique parking mandates for each zone (for example, Redmond currently does this across 50 zones), we selected the highest requirement.

After compiling parking ratios, we applied them to a hypothetical building to make them easier to compare. Most values were reported per home or other fractional size, but some categories such as daycares and schools were more easily compared as a whole building. We deducted 10 percent of a building’s total footprint (gross floor area) to get net floor area (subtracting corridors, closets, etc.) for jurisdictions that defined codes that way. We included guest parking and loading spaces where specified in the base tables. In practice, jurisdictions would round to the nearest whole parking spot, but we opted to note fractional spaces to demonstrate the variation between local governments.

We collected this data from August 2023 to August 2024 and spent much of that time reaching out to cities and counties to verify and clarify their requirements. We are grateful to the dozens of planning departments that took the time to give us feedback throughout the process.

Although zoning codes are constantly evolving, we hope this report serves as a useful point-in-time look at the state of parking mandates in Washington.

A History of Guesswork

Off-street parking requirements are a recent invention, even compared to zoning itself. New York City, famous for the first modern zoning ordinance in the United States in 1916,1 would not adopt parking minimums until 1950. After World War II, parking mandates spread rapidly alongside other exclusionary zoning practices. By 1972, 99 percent of American cities surveyed had set rules around requiring parking for new buildings.2

Cities largely took a guess at how much parking to require. Like a game of telephone, planning departments often simply copied neighboring cities’ guesses without questioning the origin of the numbers. One study found that 45 percent of senior planners and directors ranked “survey nearby cities” as the most important information when setting parking mandates. The second most influential resource for setting parking rules was the Institute of Transportation Engineers’ (ITE) Traffic Engineering Handbook. A share of planners admitted that they “didn’t know” which source of information to use, and only 3 percent used locally commissioned studies.3 This practice is still common today.

Cities that adopt parking minimums that correlate with ITE’s Parking Generation manual do so at their own risk. The studies informing ITE’s standards typically measure peak demand at a handful of suburban locations with abundant free parking and little transit service. Half of the parking generation rates from the 1987 edition were based on four or fewer studies. And 22 percent were based on just one study.4

Even with additional data points, parking demand often has no statistical correlation to variables such as store size. The wide-ranging data indicates that it’s not possible to set one parking ratio to apply to all businesses. Take this study on fast-food restaurants: a ~2,600-square-foot diner was observed to use anywhere from 16 to 42 parking spaces. The largest restaurant had half the parking demand of some smaller restaurants. Despite the ITE’s warning to use caution, cities still adopted “average” rates as legal minimums, mandating an oversupply of parking for many of the businesses the standard was based on.

The High Cost of Excess Parking

Despite 99 percent of parking spots in the United States being free to use, they come with costs that we all bear. Parking is expensive to build. On the low end, a surface parking lot might cost $5,000 to $20,000 per space. A multilevel parking garage can cost $60,000 (or more) per spot. New Sound Transit park-and-ride stations in Kent, Auburn, and Sumner ballooned to $240,0005 per parking spot.

Those costs are passed down, rolled into the price of food, rent, and taxes, whether you park a car there or not. Every parking spot per home can increase rent by 12.5 percent6 (or more than $200 per month7).

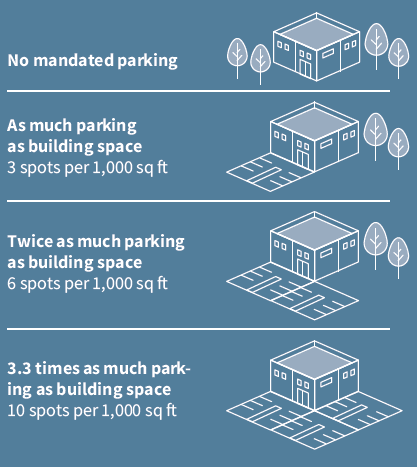

Parking costs us in dollars and space. A good rule of thumb is that parking lots are forced to be as large as the building they serve when mandates reach three parking spaces per 1,000 square feet, with 330 square feet8 for each space. That is a common value. Of the localities we studied, 61 percent required at least that much parking for offices and 80 percent required that minimum for stores. Restaurants have it even worse: the typical jurisdiction requires parking lots to be 3.3 times larger than the eatery itself.

Parking mandate guesswork comes with real-world consequences

Selah, Washington, a small town outside Yakima, requires more than twice as many parking spots for mosques as for churches, synagogues, and other temples. Is this religious discrimination? No; like many city parking mandates, those values were copied and pasted from the Institute of Transportation Engineers’ (ITE) Traffic Engineering Handbook.

Mandates to pave and pressure to sprawl: Parking takes up valuable space

Local laws often mandate far more space for parking than the size of a building or business. For certain uses it’s typical to see mandates for parking that takes up twice or three times the size of the interior. It’s common for jurisdictions to mandate three, six, or even ten spots required per 1,000 square feet of interior building space. The result is excess pavement, demolitions to make way for parking, sprawling outward to open spaces—or not building at all.

“If we had to build off-street parking at today’s standards, the entire city would be covered in asphalt.”

-Jacob Gonzalez, Planning Manager in Pasco, WA

Parking Mandates Overestimate Car Ownership and Undercut Homebuilding

Every year across Washington, homes for people are denied because they don’t also provide enough homes for cars

Homes go unbuilt across Washington because of parking mandates

In 2023, the Vancouver Housing Authority was forced to cut 40 subsidized homes from a proposed Washougal project after the city council doubled the off-street parking required downtown.

Parking mandates can make middle housing infeasible, especially on small lots

A study found that required parking made ADUs impossible on 85 percent9 of Kent’s single-detached house lots.

Parking mandates limit property owners’ options to build homes

Schoolteacher Marijean Rak moved to Mount Vernon to care for her mother, but city requirements for four parking spaces, including a two-car garage, made it impossible to build a modest, 1,000-square-foot, single-story home on a vacant lot. “This requirement is cost-prohibitive and doesn’t align with the character of the neighborhood,” she said, pointing out that most of the existing homes have a one-car garage or no off-street parking at all.10

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U3BGYL-hu0M.

Parking mandates hurt renters disproportionately

Each parking space can add $200 per month in rent, whether tenants need that parking space or not. Many don’t, since 58 percent of Washington renter households own one or zero cars.11

Even when forgoing a car or bedroom to save money, tenants are forced to pay for parking. All but one jurisdiction required an off-street parking spot for studio apartments; studios in 22 percent of Washington localities require two or more.

Most kids don’t drive a car, but parking mandates tax their bedrooms—preventing family-sized apartments

Family-sized units are commonly hit with higher parking mandates; 59 percent of Washington jurisdictions bump up parking mandates by number of bedrooms, encouraging builders to opt for smaller units and making it harder to find apartments with three or more bedrooms.

View and download this table in a new window here.

*Assumes existing residence has 2 parking spots already, for total of 3

1. ADU = Lot size: 5,500 sq ft; Unit size: 600 sq ft; 1 bedroom; First ADU on property

2. Single-detached home = Lot size: 5,500 sq ft; Unit size: 1,800 sq ft; 3 bedrooms

3. Duplex = Lot size: 5,500 sq ft; Unit size: 1,400 sq ft; 3 bedrooms

4. Apartments: 6 units in building; Studio size: 500 sq ft

Parking Mandates are a Tax on Business

Washington state’s parking regulations are a significant hurdle for small businesses, historic sites, and urban development.

Beloved establishments often can’t be rebuilt today because of parking mandates

Port Townsend is home to the state’s oldest grocery store, Aldrich’s Market. After fire destroyed the original 1889 building, a historic exemption allowed the owners to rebuild without modern parking mandates—and that flexibility was expanded citywide through a 2024 interim parking ordinance. But businesses in other cities aren’t as lucky; most Washington communities require two to six parking spots for every 1,000 square feet of a similar retail store.

Parking minimums often stand in the way of repurposing existing buildings

To convert an underutilized office to a retail store, 54 percent of cities and counties in our study would require more parking. Starting a café in a vacant space is even more difficult; twice as much parking is typically required for restaurants than retail.

Rules prevent new buildings, even on vast, underused parking lots

Olympia’s Capital Mall can’t transform its unused parking lots into a people-oriented urban center12 under current zoning rules that deem it “underparked,” with 214 fewer spaces13 than required for a shopping center.

Parking mandates can keep communities from critical amenities: Take daycares

Washington requires daycare centers to provide 75 square feet of outdoor play area per child. Local governments add on an average 87 square feet of parking per child. These rules vary by jurisdiction: 4.5 spots required for a daycare in King County; 12 in Pierce County; 36 in Puyallup.

The rules vary wildly and interpretation is up for grabs

In Bothell, would a neighborhood grocery store like Aldrich’s be considered “retail” or a “convenience store”? The latter requires twice as much parking despite not being defined in code. One-size-fits-all requirements for recreation facilities in Redmond and Mercer Island would require space-intensive bowling alleys to provide an equivalent 12 parking spots per lane.

Deviating from arbitrary parking mandates can still be contentious, slowing projects and increasing costs

Parking requirements, city waivers, and local appeals held up permits for Seattle’s new Alki Elementary School for over a year. The original 1913 school had no off-street parking, but code today requires 48 spaces. With Issaquah at the high end, requiring 226 spots (roughly 1.7 acres—larger than the Alki site itself), we found 56 percent of Washington cities and counties would require more parking to rebuild a similar-sized school.

View and download this table in a new window here.

*Also requires an unspecified number of pick-up/drop-off spots, not included in total.

1. Director = Use not specified; Planning department determines on case-by-case basis

2. Office = Ground floor; Non-customer facing

3. Retail = 900-sq-ft open to customers

4. Restaurant = All indoor; 600-sq-ft dining space; 40-person capacity

5. Bowling alley = 19,061-sq-ft building; 16 lanes; 5 employees; 100-person capacity; No dining area

6. Day care = 50 children; 10 staff; 4,000 sq-ft facility; Indoor play area: 90% of gross floor area; No business vehicle on-site

7. Elementary school = 90,278-sq-ft building; 500 students, 70 employees, 37 teachers; 26 classrooms, 11 offices; 1,310-sq-ft office space; Auditorium capacity: 275 people, 3840-sq-ft; No school buses parked on-site

Family-friendly apartments pay a parking penalty

The more bedrooms, the more parking required. Across the state, 59 percent of localities require additional parking for larger apartments, increasing barriers for family-sized units.

If Exceptions are the Rule, the Rule is Flawed

Planning departments know that parking mandates are set too high, which is why exceptions keep getting added to city codes over the years. These carve-outs satisfy the practical need to make building feasible for properties lucky enough to qualify, but they can force builders into uncertain discretionary processes. Even when the city itself is the applicant, as with Seattle’s Alki Elementary, bending the rules can be controversial. Even the “optional” minimums in cities such as Lacey and Lakewood require a special approval to supply less parking than the suggested ratios. We categorized this as a waiver process.

Piling on exceptions to the rules makes zoning codes more complicated. Even an educated city planner can misinterpret how much parking is actually required. That’s what happened in Washougal. City officials thought they were adopting the same downtown parking standards as neighboring Camas14, but they overlooked a small section of Camas’s code. That section, “Units of measurement,” gave steep parking discounts to multistory buildings, cutting requirements for new buildings by half or more. Without copying the exception, Washougal inadvertently outlawed within its own city limits the kind of in-demand new housing springing up in Camas.

Types of Parking Waivers

Near transit: In Vancouver’s transit overlay districts builders are only required to build 75 percent of the parking mandated by the underlying zone.15

Downtown and special districts: Bellingham’s seven urban villages16 each have their own parking requirements .

On-street parking: In Bothell, new on-street parking spaces may be counted toward minimum parking requirements for downtown commercial buildings.17

Existing buildings: In Tacoma, no additional parking is required for pre-2012 buildings in commercial districts when they undergo a change in use.18

Miscellaneous: Olympia automatically grants 10 percent reductions when asked. Directors are authorized to waive up to 40 percent under the right circumstances if applicants submit a report justifying the request.19

Parking mandates are as specific as they are arbitrary

Similar uses, like libraries and archives, can require very different space for parking. Categories are tied to building area or to units or employees—or a combination! It’s not uncommon for jurisdictions to specify parking ratios for over a hundred different building types. Here’s a snapshot from the City of SeaTac:

- Butterfly or moth breeding facility: 1 parking spot per 250 square feet

- College dormitory: 1.5 parking spots per bedroom

- Hospital: 1 parking spot per bed plus 5 spots for every 2 employees

- Tavern: 1 parking spot per 250 square feet of leasable space

- Micro-winery or brewery: 1 parking spot for every 40 square feet of tasting room space plus 1 per employee

- Library: 1 parking spot per 200 square feet of building

- Public archive: 1 parking spot per 400 square feet of waiting or review area plus 1 per employee

- Cemetery: 1 parking spot per 40 square feet of chapel plus 1 per employee

- Bowling alley: 5 parking spots per lane plus 1 per employee

The Ninebark Apartments provide 1.6 parking spaces per home.

The site would require even more parking if located downtown after Washougal City Council increased parking mandates in 2023.

Right-sizing parking lots: Parking reform in Washington

Washington cities have begun rethinking these rules. So far in 2024, Port Townsend and Spokane have eliminated parking mandates altogether, returning decisions about parking needs to individual property owners. Other cities like Bellingham and Redmond are in the process of reducing or removing their parking mandates.

When given full flexibility, developers frequently still choose to build parking but in different numbers than zoning codes prescribe. A comprehensive study of Seattle’s 2012 parking reform found that 70 percent of multifamily buildings still chose to build off-street parking. The flexibility was widely used: 59 percent of new homes benefitted from reduced construction costs by providing fewer parking spaces than previously mandated.20 Across the 868 new developments studied, the market built a total of 40 percent less parking than what had been required. This correction was exactly in line with an earlier King County study that found that 40 percent of parking spaces in multifamily buildings sat empty overnight.21

Builders in small Washington cities have also taken advantage of full flexibility. The first new building to be permitted in Bellingham’s Old Town district after repealing parking mandates in that zone included 2.3 times the number of homes (or 48 new dwellings) as would have been allowed before. If it turns out that there aren’t enough parking spaces to attract tenants, builders have multiple options to provide additional parking on neighboring properties.22

Zoning is ultimately just one barrier to making building feasible. Jesse Bank, director of Spokane’s Northeast Public Development Authority (PDA), has been wrestling with how to provide more parking in a proposal for a building that will house the future PDA office, workforce housing, and a 24-hour daycare center. The city no longer requires parking, but kids still need to be safely dropped off at daycare, and an appraiser determined that fewer than one parking space per home could decrease the building’s ultimate value by as much as $1 million dollars. “Zoning is out of the way, but it’s only one of five or six things,” Bank said.

While Bank is trying to find a nearby property for additional surface parking in the short term, he imagines that the need for parking could decrease over time. A rapid bus line will be installed out front in the next two years, likely spurring additional investments in the neighborhood and making the street more walkable as a whole.

As financial lenders and roadways evolve over time, the zoning code is written to allow the surface parking lot built today to transform into a community building when the conditions are right. By merely restoring property owners’ right to determine their own parking needs, Spokane has allowed itself to respond to the changing market when the time comes.

To unlock the same kind of innovation and opportunity that Spokane, Bellingham, and Port Townsend are eyeing for their communities, cities and counties across the state—and Washington state itself— may want to take another look at their own zoning codes. The origin of any town’s parking mandates is likely to have been lost long ago, but these ratios continue to shape the places we love. The decisions we make now will determine whether the neighborhoods of the future have abundant housing, local businesses, and community spaces—or an abundance of unused parking lots.

About the Author

Catie Gould (pronounced “Go͝old”) is a senior transportation researcher for Sightline Institute, specializing in parking policy. Her research and reporting have helped numerous jurisdictions reduce or repeal their parking mandates.

Catie brings a decade of experience in engineering and data analysis to her work at Sightline. Prior to joining the organization, she also led BikeLoud PDX, advocating for better bike and bus infrastructure in Portland, and wrote about local transportation issues. She holds a bachelor’s degree in material science and a master’s in mechanical engineering from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute.

Originally from rural Maine, Catie loves exploring new cities, camping, and playing music. She lives in Portland.