UPDATE, February 7, 2025: SB 5184 passed the Senate Housing Committee 5-1. The bill was amended to exempt a one-mile radius around the SeaTac airport.

UPDATE, January 29, 2025: SB 5184 was updated to apply a cap of 0.5 mandated parking spaces per home to all cities. The transit-related housing exemptions were also removed from the bill. View the substitute bill via this page (folder navigation: Public hearing / SB 5184 / Amds/Proposed Subs / “PSSB….”).

Find audio versions of Sightline articles on any of your favorite podcast platforms, including Spotify, YouTube, and Apple.

In 2023 Washington state adopted a raft of bills unlocking more home choices, at more affordable prices, in cities and towns across the state. It was hailed as the year of housing.

The 2025 legislative session could be the year of parking reform, with the promise of taming rents and housing costs, curbing sprawling development, and prioritizing things communities want, like trees, affordable housing, senior living facilities, and daycares, rather than unneeded pavement.

Last week, Washington state housing affordability champion Senator Jessica Bateman introduced the Parking Reform and Modernization Act, SB 5184. The bill would cap how many parking spots local governments can require for new homes and commercial buildings, and give full parking flexibility to a set of building types that need it the most. The bill also has a companion in the House of Representatives: HB 1299, sponsored by Representative Strom Peterson.

Commonly adopted in the 1950s and ‘60s, parking mandates prescribe a pre-determined number of parking spaces for every new building, assigning unique quotas for hundreds of different uses, from churches to bowling alleys, butterfly breeding facilities to daycares. These regulations increase construction costs, outlaw traditional main streets and historic neighborhoods, block building conversions from one use to another, and make entire properties impossible to build on simply because they lack space for a sprawling parking lot. What’s worse: many of those mandatory parking spots end up sitting empty. Despite the ubiquity of highly specific parking mandates in local permitting, city officials rarely know where the numbers originated but must enforce them nonetheless.

This legislation would set a new course by creating consistent statewide standards to unlock more opportunities for homes and small businesses alike. And to be clear, it would not ban parking: builders would still be free to include as much parking as they decide they need.

The bill is scheduled for a hearing are the Senate Housing committee on Friday January 24th.

Thanks to William Dougall for supporting a sustainable Cascadia.

Our work is made possible by the generosity of people like you.

What the bill does

In short, SB 5184:

- Caps residential mandates at 0.5–1 parking space per home

- Caps commercial mandates at 1 parking space per 1,000 square feet

- Provides full parking flexibility for building types that need it the most

- Applies everywhere in Washington, towns large and small

- Expands existing transit exemptions for housing

- Does NOT place any restrictions on how much parking people can build if they deem it right for their project to succeed

Caps residential mandates at 0.5–1 parking space per home

In the past two years, the Washington state legislature has legalized granny flats, fourplexes, and co-living buildings statewide. But outside of a tiny portion of urban residential lots near frequent transit that those bills exempted, excessive parking mandates continue to undercut home building.

In Pasco, for example, the rules require two parking spots for every apartment. In Marysville, code mandates six parking spots for a duplex. Meanwhile, nearly sixty percent of Washington renter households only own one car or no car at all.

To keep unnecessary parking mandates from hindering much-needed new homes and affordability, SB 5184 would prevent towns and cities from requiring more than 1 parking space per home. Counties and non-code cities would allow even more flexibility, with caps set at 0.5 parking spaces per home. This latter ratio would apply to larger cities, including Aberdeen, Bellingham, Bremerton, Everett, Seattle, Richland, Tacoma, Vancouver, and Yakima.

Allowing builders to go below one parking spot per home enables natural “unbundling” in multifamily buildings. When there are fewer spaces than homes, owners have to charge for parking separately, and that lets tenants who don’t want a parking space save money on total rent. Single-detached houses in those jurisdictions would still provide one parking spot per home, because as a rule, local governments round up to the next whole number.

Caps commercial mandates at 1 parking space per 1,000 square feet

SB 5184 also provides relief for businesses. Assuming a typical parking space size of 330 square feet, the legislation’s cap of one space per 1,000 square feet would ensure that governments can’t require parking that amounts to more than a third of the floorspace of any commercial property. Today in Washington, the typical requirement for an office or retail store is just over three parking spaces per 1,000 square feet, requiring a parking lot roughly the same size as the footprint of the building it serves.

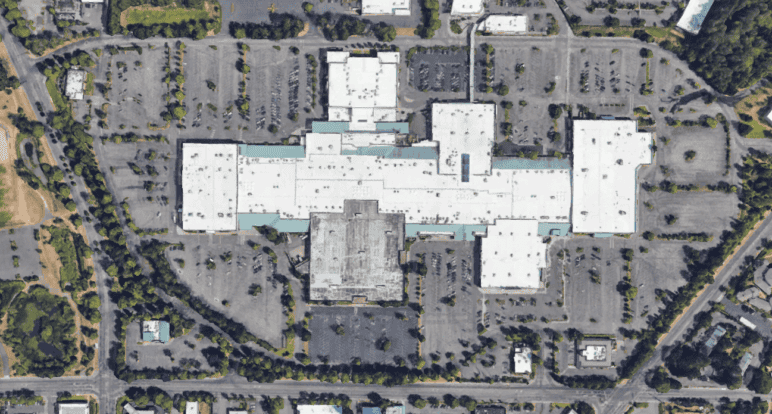

The bill’s cap could yield big benefits, not only for small businesses, but also for repurposing underused parking lots. The Capital Mall in Olympia, for example, has plenty of vacant space on its periphery where new commercial buildings or homes could be added. But making better use of this land is impossible because of Olympia’s parking mandates. The mall property is already 214 spaces short of meeting the shopping center requirement of 4.5 parking spaces per 1,000 square feet.

Provides full parking flexibility for building types that need it the most

In addition to setting universal caps on parking mandates, SB 5184 completely exempts from mandates the following select set of specific uses, giving builders full flexibility to pick the number of parking spots they deem appropriate:

- Buildings undergoing a change of use (as from an office to a coffeeshop)

- Small residences under 1,200 square feet

- Small businesses under 5,000 square feet

- Affordable housing

- Senior housing

- Housing for people with disabilities

- Facilities that serve alcohol

- Childcare facilities

- Commercial spaces in mixed-use buildings

These are uses for which parking mandates are particularly troublesome, like for small residential and commercial spaces where every square foot matters. Others are uses people in Washington greatly need, like affordable housing and daycares.

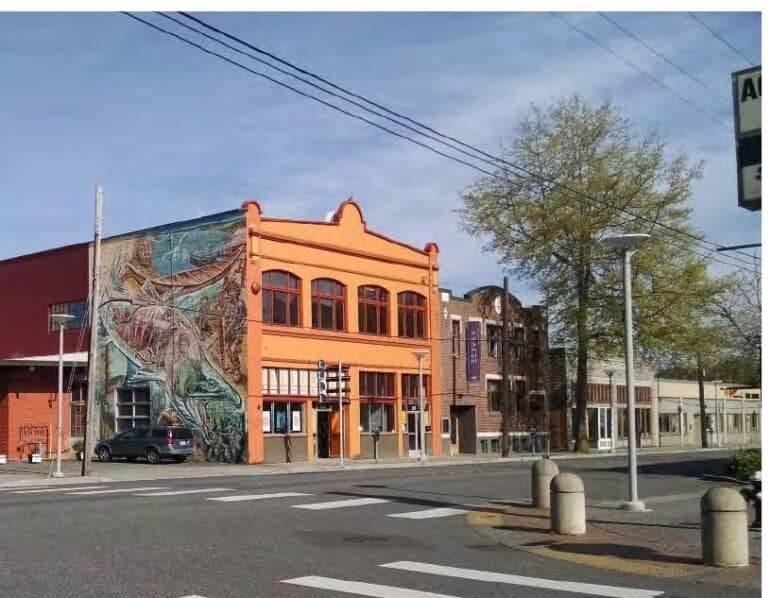

Relaxing parking mandates on use conversions of existing buildings has proven to be an essential policy for revitalizing vacant storefronts or converting old commercial buildings to housing. Not only do these reforms remove barriers to small, locally owned businesses and encourage mom-and-pop businesses competing with big box stores and national chains, they re-legalize “main street” style neighborhoods. For example, a historic former laundry in Bellingham, Washington, was able to transform into a cider company, restaurant, art gallery, and performing arts theater because it was exempt from modern parking mandates.

Mixed-use buildings (typically with ground floor commercial and residences on upper floors) were big beneficiaries of parking reform in Buffalo, New York. Ending requirements to provide parking for both the tenants and commercial customers—regardless of whether those spaces could be time-shared—removed a major financial barrier for builders.

Applies everywhere in Washington, towns large and small

The cap and exclusion sections of SB 5184 differ in key ways from parking legislation previously passed or proposed in Washington. The bill’s reforms apply statewide to GMA cities, regardless of size or nearby frequent bus service. That’s because excessive parking can thwart new housing and businesses in communities of all sizes.

For example, last year, we reported on an example in the small town of Washougal, Washington, where an affordable housing development was cut in half after the city council increased parking mandates in the downtown area where it was proposed.

Down the road near Ridgefield, Washington, daycare operator Dana Christiansen had to abandon a property she purchased because she was a few parking spaces short of what the county required, despite a significant shortage of daycares in the area. “We were having a hard time getting the building situated with the amount of playground that we require,” Christiansen told Sightline. “But parking is what killed it.”

The simplicity of letting entrepreneurs and property owners decide how much parking they want for themselves is why small cities and towns are leading the way in fully repealing their parking mandates. “It’s just not a good use of our time,” said Emma Bolin, Director of Planning and Community Development for Port Townsend, Washington.

While vehicle use does vary based on things like neighborhood walkability, demographics, and transit access, parking mandates are inherently problematic policy anywhere. It is not possible for any one ratio to provide exactly the right amount of parking spaces for one restaurant and not result in excess pavement for another. Or worse, block new businesses from opening at all.

Not tying mandates to transit proximity also lightens the load on local government administration. Cities would avoid the headache of constantly updating zoning maps based on transit service changes. Homeowners also won’t find themselves unexpectedly on the wrong side of a negotiated political boundary, being forced to pave over their backyard in order to, say, build an accessible cottage for an ailing relative, while their neighbors do not.

Expands existing transit exemptions for housing

Current state law already places some guardrails on how many parking spaces local governments can require for certain housing types near transit. This includes middle housing, accessory dwelling units (no parking required within a half-mile of a major transit stop), and market-rate multifamily homes (capped at 1 parking spot per bedroom or 0.75 per unit within a quarter-mile of 15-minute transit stops).

Under the Parking Reform and Modernization Act, multifamily housing, middle housing, and accessory dwelling units would all receive full parking flexibility within a half-mile walking distance of 15-minute transit service. While this seems like a slight definition change, the shift from transit stops to transit service expands geographic coverage and future-proofs zoning boundaries from bus stop consolidations or changes along the route, following in the footsteps of Oregon. The new, simplified rule would apply to cities over 10,000 people within counties that have a population density over 100 people per square mile. That list includes Benton, Clark, Island, Kitsap, King, San Juan, Snohomish, Spokane, Thurston, and Whatcom counties.

Existing state laws that cap excessive parking mandates for affordable housing, senior housing, and people with disabilities near transit would no longer apply. Under SB 5184, those categories would receive total flexibility statewide, regardless of transit service.

Does NOT restrict how much parking people can build

It bears repeating that SB 5184 only limits local governments’ ability to require parking. It does not impede anyone from building as much parking as they wish on their own property, nor does it outlaw any existing parking lots. The bill simply ensures more options for homebuilders and business owners to choose for themselves how best to serve their future tenants or customers.

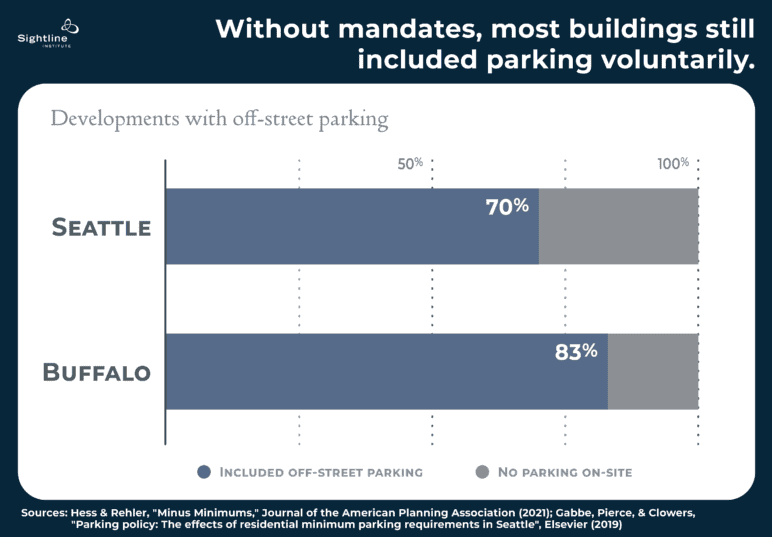

When builders do have the option to provide no parking at all, they often still choose to build it. Off-street parking, like other optional amenities such as dishwashers and laundry machines, is still important to many people. Two separate studies of what happened after parking mandates were eliminated in Seattle and Buffalo found that 70 to 83 percent of buildings, respectively, still built parking on-site. They just right-sized it to what they anticipated their target market of customers would want to have.

A bigger, bolder statewide reform

If successful, Washington could join a growing list of states that are taking action against excessive parking mandates. In recent years Oregon, California, Colorado, Vermont, and others have won statewide parking reforms.

Two years ago, Washington was unsuccessful in reining in parking mandates with HB HB 1351, sponsored by Representative Julia Reed. That bill would have eliminated parking mandates solely for properties within frequent transit zones. Facing opposition from the Association of Washington Cities and from suburban jurisdictions, the bill failed to advance to the house floor for a vote.

This time, transit proximity is just one item among a long list of exemptions. The shift represents a growing awareness of arbitrary, excessive parking mandates as an issue for all communities, regardless of how much people drive.

Unlocking housing abundance

Parking flexibility is a powerful lever for enabling the creation of more homes, in all shapes and sizes, for Washingtonians. A recent study from Colorado calculated that compared with status quo mandates, if builders could provide 0.5 parking spaces per home near transit and 1 parking space everywhere else, 41 percent more homes would become financially feasible to build. That one regulatory change was more powerful than legalizing accessory dwelling units and larger apartment buildings combined, if those new homes still were subject to excessive parking mandates.

Where parking is flexible, more homes sprout up as a result. Bellingham piloted a “no mandate zone” in its industrial Old Town district and saw a new residential building plan for twice the number of homes as it would have been allowed under the old rules. Now Bellingham leaders have voted to extend that same flexibility to all properties citywide.

Other Washington cities have also taken action to relegate parking mandates to their historical dustbin. In 2024, Port Townsend and Spokane fully repealed parking mandates, and Shoreline is on the way. While Spokane hasn’t been collecting data since it removed parking mandates, the benefits are already showing anecdotally.

“Most proposals are building at levels slightly below what would have been required, but they are finding that parking is still necessary for obtaining financing and being competitive in the real estate market,” explained Spencer Gardner, Spokane’s planning director. “The biggest impact seems to be for small-lot infill or other difficult situations where the added flexibility can be a difference-maker in a project going forward.”

With SB 5184, Washington lawmakers have the opportunity to apply these lessons at the state level, so that every community can get more of the homes and businesses that they truly need and want—and less of the asphalt that they don’t.