Takeaways

- Unfunded inclusionary zoning is not inclusionary. To fix it, fund it.

- Unfunded inclusionary zoning—the conventional model of IZ—is broken, both as policy and politics. Its unfunded mandate for affordability can backfire by making apartment development a money-losing proposition, sacrificing both market rate and affordable homes. And when unfunded IZ is coupled with legislation to allow more apartments, its policy flaw divides the coalitions needed to pass the legislation.

- An alternative gaining ground across the US is funded inclusionary zoning, which leverages public dollars to cover the cost of mandating affordable homes in new developments, and it’s a vast improvement on both the policy and political fronts.

- As Washington state works to address its severe shortage of homes, it can look to examples of funded inclusionary zoning policies in Portland, Baltimore, Chicago, and its own Shoreline for lessons on crafting a strong, smart policy—one that could take advantage of a peculiarity of its property tax code and maintains cities’ tax revenues.

- Getting this right could meet the opportunity presented by the state’s recent investments in robust transit networks while unlocking thousands more homes across the Evergreen State, especially for workforce and lower-income residents.

On Labor Day weekend, Sound Transit opened four more stops of its light rail line north of Seattle. But when I took my inaugural ride, I had my eye on something equally important as the shiny new transit line to the future of the region’s cities: new apartment buildings sprouting up near the stations.

And not just any apartment buildings, but four of them built through a rare new policy that may be a key to digging out of the statewide housing shortage: funded inclusionary zoning.

Public investments in rail and bus transit create immense opportunities for healthy, low-carbon, economically diverse communities clustered around jobs, services, and transportation choices. But only if those communities also allow ample mixed-income housing to grow up alongside those hubs.

One way some North American cities have tried to meet that challenge is by requiring private developers to offer a set percentage of their new apartments at reduced rents, known as inclusionary zoning (IZ). But there’s a big problem with that. If the IZ mandate is unfunded, it actually backfires: the rent revenue lost on the required affordable apartments can make it a money-losing proposition to construct the building in the first place, and homebuilders walk away from projects altogether. This conventional model of IZ—unfunded inclusionary zoning—impedes construction of much-needed affordable and market-rate homes, and squanders the new transit-unlocked opportunities.

The good news is there’s a way to avoid the unfunded-IZ backfire: use public dollars to cover the cost of the affordability mandate. That is, funded inclusionary zoning.

When IZ is funded in this way it doesn’t harm the financial feasibility of homebuilding, and so it avoids the unintended consequences of unfunded IZ that worsen the housing shortage and make rents higher for everyone. And funded IZ still ensures that all new apartment buildings include affordable homes and create mixed-income communities.

In the following I:

- discuss why funded inclusionary zoning is both good politics and good policy, and that it matters how you fund it

- share examples of places doing it already (Portland, Baltimore, Chicago, Shoreline, and Washington state’s optional version), and

- specify how Washington legislators could enable this powerful tool to help more residents find the homes they need and want, all across the Evergreen State.

Legalizing larger apartment buildings near jobs and transit is a critical piece of unfinished business for cities throughout North America to meet the long backlog of homes residents need—from young people starting out to retirees downsizing their digs, growing families to growing workforces. Unlike unfunded inclusionary zoning that can backfire and thwart that goal, funded IZ can unlock an abundance of homes—including income-restricted homes—in urban centers with both employment opportunities and robust transit connectivity. For Washington state in particular, funded IZ offers a solution for equitably leveraging the state’s transit investments and creating communities where all neighbors are welcome.

What’s different about funded inclusionary zoning

Funded IZ is good politics

Funded IZ is not just a smart policy solution. It’s also a promising political solution.

Proposals to allow large apartment buildings tend to intensify disagreement over affordability requirements, which can fracture the broad coalition needed to pass zoning legislation. Case in point: Washington state’s transit-oriented development (TOD) bill to legalize apartments near transit that died two years in a row.

State legislatures across North America are also susceptible to the impasse that played out in Washington: most left-leaning Democratic legislators won’t vote for a TOD bill without IZ, while many centrist Democrats and all Republicans won’t vote for a bill with IZ. Even when policymakers are committed to TOD, this stalemate thwarts the most important zoning reform for creating housing abundance and affordability: allowing apartment buildings in more places in cities.

Funded IZ could be a winning compromise. It addresses the left’s concerns about guaranteeing affordable homes near transit and jobs by mandating them in every new building. And it addresses the center’s concerns about unfunded IZ suppressing homebuilding and shunting development away from transit stations.

Meanwhile, funded IZ asks that progressive Democrats accept a policy some might feel fails to make developers pay for low-income housing. And it asks that centrist Democrats and Republicans tolerate a government mandate on the private sector to provide rent-restricted apartments.

The outright winners in this big compromise, importantly, are all the residents who get more homes they can afford, including more deeply affordable housing options, in places convenient to their jobs and robust transportation choices.

Funded IZ is good policy

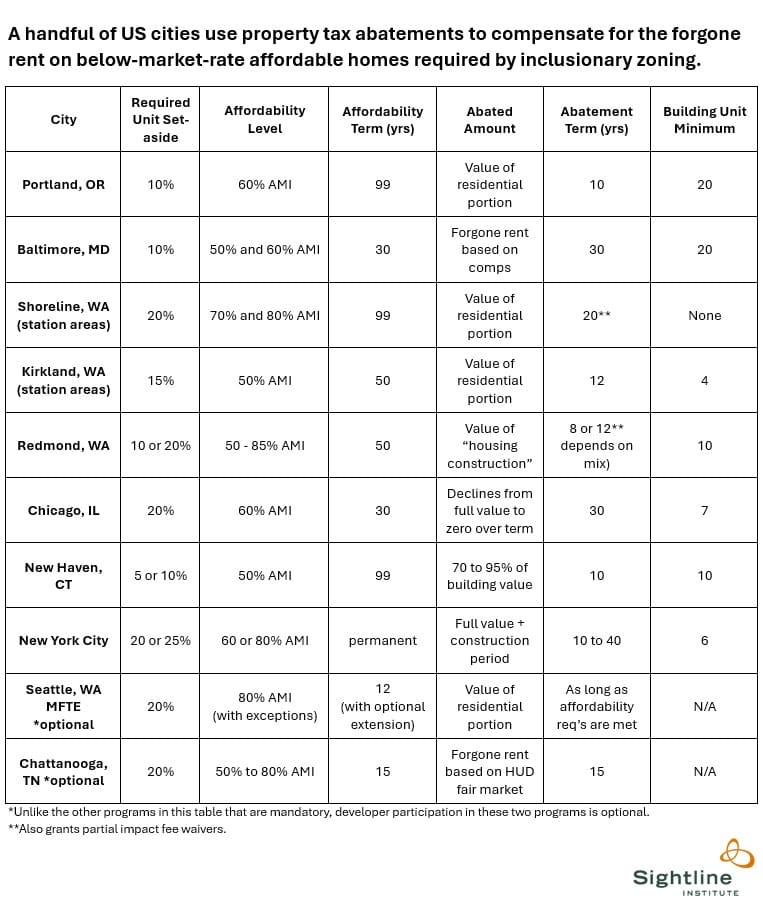

At present, funded IZ is uncommon. To the best of my knowledge, only three US cities currently have programs that at least come close to the ideal model of fully funded IZ: Portland, Oregon; Baltimore, Maryland; and Shoreline, Washington.1

All three of these use property tax abatements to fund their inclusionary zoning mandates. The owner of a new apartment building gets a reduction in their property tax bill to offset the rent income they forgo by providing below-market-rate homes. If the tax exemption fully covers that deficit, homebuilding projects pencil as well as they would without the affordability mandate, so there’s no loss of housing production.

An advantage of utilizing property tax breaks is that an IZ policy can be designed so that the funding level automatically adjusts to local variation in market conditions, as well as to changes in those conditions over time. This ensures that the tax benefit is neither too big nor too small. In contrast, for conventional, unfunded IZ, cities typically do some fuzzy math to lock down requirements in advance, inevitably resulting in a chilling effect on homebuilding that varies haphazardly across location and time.

Washington state’s property tax system is particularly well-suited to funding IZ with abatements because there is no loss of property tax revenue. Even if a new apartment building is tax-exempt, its value still adds to the tax base. And as with all new construction, the new property tax revenue created is not subject to the state’s one percent annual cap on total revenue increase. A city’s tax revenue rises just like it would when any new building is constructed, and all property owners pay a tiny fraction more to cover the revenue not collected from the abated new apartment building.

This kind of community-funded mixed-income zoning—funded IZ—is the best subsidized-housing policy innovation that Sightline knows about anywhere in North America. It offers a path on both policy and politics to marry the imperative of building truly abundant market-rate housing in our cities—in compact, walkable, low-carbon, mixed income neighborhoods—with the need for far more below-market rental homes.

Recap: It’s important to fund IZ, and to fund it the right way

In a previous article I described how unfunded inclusionary zoning (IZ) undermines its own intent by impeding homebuilding and how it would be particularly prone to backfire if imposed statewide. Offsets granted by cities can reduce IZ’s unintended consequences by compensating for the rent income owners lose on the required below-market homes. Funded IZ is a type of offset: public dollars cover the loss, and in effect, pay for the rent subsidy. In that way, funded IZ is like any other public housing program, from Section 8 vouchers to Vienna-style social housing.

However, some politicians see a tempting alternative here: what if we counted the right to build bigger buildings as the subsidy? Then we could say, “We’ll upzone this property, but only if a certain percentage of new homes on it rent below market price.” Magic: the public could get subsidized housing without anyone’s taxes going up!

Unfortunately, that is a flawed approach for funding IZ.2 What looks like a free lunch is actually a lunch with a much higher, invisible price—one paid by tenants all over the city. Upzoning land to allow larger buildings catalyzes the development of new housing on it. But the financial burden imposed by IZ does the exact opposite, impeding construction.

This “value capture” of upzones with IZ sabotages the intent of enacting the upzones in the first place, which is to mitigate the housing shortage by creating more homes. It’s like one step forward and one step back. Funded IZ cannot deliver on its promise if it’s funded through upzones. It must be truly funded—with dollars.3

Who’s doing funded inclusionary zoning today?

Portland, OR: Funded IZ made better

Portland adopted its first iteration of funded IZ in 2016. It required all multifamily developments with 20 or more units to set aside for 99 years either 10 percent of homes at rents affordable to 60 percent of area median income (AMI) or 20 percent of homes at 80 percent AMI. In exchange, the city granted a 10-year property tax exemption on the value of the entire residential portion of the building for projects in the downtown area. But outside downtown, it limited the exemption to only the value of the subsidized homes—a much smaller tax break.

Portland updated its program in March 2024 after it became clear that because it fell far short of funding the IZ outside of downtown, it was suppressing homebuilding there. The fix was to expand the tax exemption on the whole building to everywhere in the city. The city also took the opportunity to focus on deeper affordability and opted not to fund the 80 percent AMI option outside downtown.

Portland’s IZ abatements will reduce the city’s annual property tax revenue by an estimated $41 to $83 million, which, on the high end, is 0.5 percent of the total collected. (For comparison, Seattle spends about 4.5 percent of its property tax revenue on affordable housing subsidy.) And the program will yield an estimated 300 rent-restricted homes per year at a cost to the public of about $275,000 per home.

In Portland, incorporating affordable homes in privately developed housing is more cost-efficient than typical 100-percent-affordable projects developed by nonprofits. My colleague Michael Andersen writes:

If you do the math to calculate the public’s cost per home, the below-market housing created via fully funded inclusionary housing is less expensive than a comparable home created by a local housing bond. That’s presumably because the affordable homes hitch a ride on a project that was already being financed.

This improved bang for the buck with funded IZ is likely in other cities as well.

A shortcoming of Portland’s program is that it sets a static, citywide IZ requirement based on upfront economic analysis. The problem is, the balance between the forgone rent revenue and the tax exemption is highly sensitive to market rents, which vary by neighborhood and over time.

Inevitably, in some instances Portland’s IZ mandate will end up underfunded and have the unintended consequence of suppressing homebuilding. The equation could also tilt in the opposite direction and overfund, which is not ideal, but at least still has the upside of accelerating the production of both market-rate and affordable housing.

According to the City of Portland, as of September, four midrise apartment developments had applied for new permits under Portland’s updated, more fully funded IZ policy. In addition, fifteen projects in various stages of planning have updated their previous permits to take advantage of the new IZ rules and build more homes.

Baltimore, MD: Calibrating funded IZ to actual costs

Baltimore’s new funded IZ program went into effect in July 2024, replacing a program that produced little affordable housing because it was insufficiently funded. The new policy requires all multifamily developments with at least 20 units to set aside for 30 years 5 percent of homes at rents affordable to 50 percent AMI, and another 5 percent of homes affordable to 60 percent AMI.

Like Portland, Baltimore grants a property tax reduction to offset the lost rent income. But instead of a predetermined abatement, each year it grants the owner a tax credit equivalent to the building’s actual forgone revenue—that is, the difference between the rent collected from each required below-market-rate unit, and the rent collected from a comparable market-rate unit.

It’s an elegant scheme. If the tax credit matches the full costs of meeting the affordability mandate, the policy has zero impact on the financial feasibility of constructing housing. That’s because a building’s net operating income—and therefore its value—will be the same as it would have been without IZ. And that remains true even if market-rate rents change over time, because the size of the tax rebate automatically adjusts for such changes every year. Consequently, in the equation for evaluating the go/no-go decision on a proposed homebuilding project, a rent-restricted unit looks just like a market-rate unit.

The Baltimore funded IZ design also avoids a serious flaw typical to conventional, unfunded IZ, namely, that it sets static requirements based on economic analysis loaded with assumptions and likely done years in advance. This analysis can’t anticipate changes in construction costs, interest rates, and rents, and also is typically too distilled down to account for variations in market strength within a city.

Even though Baltimore’s funded IZ program is based on actual rent differences, it’s still not quite fully funded. Owners incur administrative expenses, too, for tenant income qualification and assorted compliance red tape. Building owners also must float the forgone rent revenue throughout each year until they receive the tax refund. To fully fund the program, the city could give the tax exemption a little boost—say, a few percent—to cover those costs that are above and beyond the forgone rent.

This year, Chattanooga, Tennessee, launched a program that works like Baltimore’s, though developer participation is optional, not mandatory. The tax abatement is equal to the rent difference plus a two percent cushion to cover the administrative costs of participation.4

Shoreline, WA: Transit-focused funded IZ

In 2015, the city of Shoreline, Washington, just north of Seattle, adopted mandatory funded IZ in the areas surrounding its two Link light rail station areas, with the following parameters:

- 20 percent of homes rent-restricted

- Affordable to 70 percent AMI for studios and 1-bedrooms

- Affordable to 80 percent AMI for 2+ bedrooms

- Rent restriction required for 99 years

- 20-year property tax exemption of the value of the residential portion of building

So far, four 7-story apartment buildings subject to Shoreline’s funded IZ are under construction or completed: two near the 148th Street station and two near the 185th Street station. However, several proposed station area projects are on hold, mainly because high interest rates and construction costs in recent years have made financing much more difficult.

These projects in purgatory demonstrate how sensitive development feasibility is to changing economic inputs. When they were proposed they penciled; but now, perhaps two or three years later, they don’t. It would be unfair to blame Shoreline’s IZ for that. But if not fully funded, IZ can be the straw that breaks the camel’s back on marginal development pro formas.

Future tax breaks get “discounted,” but the local developer of one the above-mentioned projects on hold told me that there’s still a big difference between Shoreline’s 20-year abatement term and Portland’s 10-year, for example. If Shoreline’s abatement was only ten years, his firm would likely have never pursued the project—another illustration of the sensitivity of real estate development economics.

Other partially funded IZ programs

Redmond, WA

Redmond’s base IZ requirement for multifamily development is a relatively modest 10 percent of units at 80 percent AMI. The program also grants a density bonus of one extra market-rate unit for every affordable unit included to meet the IZ mandate. The city has a separate MFTE program with a mix of options that mostly require more and deeper affordability than the base IZ mandate—in some cases, the IZ units can cover a portion of the MFTE requirement. The city also grants partial exemption of impact fees, but only for units at less than 80 percent AMI. With all the options, it’s difficult to nail down how well Redmond’s IZ program is funded, but compared with Shoreline generally, it appears to be further from full funding. Under these rules, Redmond has seen multiple large apartment buildings constructed near future light rail stations.

Kirkland, WA

Kirkland’s base IZ requirement for multifamily development is 10 percent of units at 50 percent AMI For buildings 65 feet or taller located in transit station areas, it jumps to 15 percent of units at 50 percent AMI. The city offers bonuses on height, FAR, or an additional two market-rate units per required affordable unit, depending on the zone. It has a separate MFTE program—either 8 years for 10 percent of unit at 50 percent AMI, or 12 years for 15 percent of units at 50 percent AMI—and allows the affordable homes required by IZ to count toward meeting the MFTE requirement. For typical market conditions in Kirkland, MFTE would fall far short of fully funding 15 percent of units at 50% AMI.

Chicago

In 2021, Chicago adopted citywide mandatory IZ that most commonly requires a set-aside of 20 percent of homes affordable to 60 percent AMI for 30 years, in all multifamily developments with seven or more units. Also in 2021, the state of Illinois authorized a range of property tax breaks for multifamily housing if it includes rent-restricted affordable homes.

Most new housing developments that comply with Chicago’s IZ are eligible for a tax abatement. And most qualify for the biggest one allowed, which is an exemption on the building’s full value during the first three years, followed by a series of reductions in the exempted value down to zero over the 30-year term. Compared with Portland, Baltimore, and Shoreline, Chicago’s IZ is much further from being fully funded. That’s because while its abatement is in the same ballpark as those others, its affordability requirement is more costly.

New Haven, CT

Depending on location, New Haven, CT, requires 5 to 10 percent of units at 50% AMI, plus a 5 percent set aside for Section 8 voucher holders. It grants a tax exemption between 70 and 95 percent of the building’s value for 10 years, along with capacity bonuses and parking waivers. Slow uptake suggests the program is insufficiently funded.

New York City

New York City has mandatory IZ in medium to high density areas parts that applies when upzones are granted. These projects typically qualify for “428x” affordable housing tax exemptions. Depending on location and project size, IZ requires from 20 to 30 percent of project floor area reserved for people earning 40, 60, 80, or 115 percent of AMI. The 428x program requires unit set asides of 20 or 25 percent and weighted affordability of 60 or 80 percent AMI. The property tax abatements range from 10 to 40 years, with an additional three or five year abatement during construction.

Washington state’s optional funded IZ: MFTE

Way back in 1995, Washington state created the multifamily tax exemption (MFTE) that authorizes cities to grant property tax abatements on newly constructed multifamily buildings. Cities can choose the level of affordability that qualifies a building for an abatement, and developers can participate or not. MFTE is an optional version of funded IZ.

Seattle’s implementation of MFTE typically requires 20 percent of homes affordable to 80 percent AMI in exchange for exempting the value of the residential portion of the building. The abatement lasts as long as the owner provides the required affordability, for a term of up to 12 years, with the option for an extension.

MFTE has produced thousands of below-market homes in Seattle. Historically, some multifamily developments have opted to use the program and some have not, an indication that the value of the tax exemption is fairly well matched to the forgone rent, give or take.

The City of Shoreline’s version of MFTE requires the same affordability levels as its mandatory IZ in light rail station areas (see above). The difference is that for MFTE, the requirements remain in effect only as long as the tax abatement is granted, while the station-area IZ requires affordability for 99 years, but only grants a 20-year tax break.

Since 2015, Shoreline’s MFTE has produced 415 rent-restricted homes, with hundreds more in the pipeline. The city (pop. ~60,000) gained about 2,000 housing units from 2015 to 2023, indicating that the vast majority of developers opt in to MFTE.

MFTE, like conventional IZ, relies on preset requirements that don’t adjust for local variation or change over time. MFTE’s critics point out that in some instances the required affordability levels are similar to market-rate rents, in which case projects don’t deserve a tax break. Washington could avoid that issue by adopting Baltimore’s method of setting the abatement based on actual forgone rent in each building.

On the other hand, MFTE’s uniform mandate can end up being beneficial, because it has stronger incentive power in places with weak real estate markets.5 This built-in bias often aligns with public policy goals to add new housing in lower-rent areas that struggle to attract any homebuilding at all.

That’s also why MFTE’s designers included an option that grants the tax abatement without requiring any rent-restricted affordable units at all. They recognized that all by itself, building market-rate apartments delivers a wide range of public benefits aligned with state and local policy goals, and in some cases, those benefits justify a no-strings-attached incentive.

The funded IZ opportunity for Washington state

Washington is already set up for funded inclusionary zoning

Washington authorizes IZ in what state law calls “affordable housing incentive programs.” Cities must grant offsets, but the law does not require them to fully compensate for the cost of the affordability mandate. Notably, the list of sanctioned offset types does not include property tax abatements.

State law enabled Shoreline to impose IZ in its light rail station areas because it was also adopting upzones, an approved offset type. The city opted to also fund the IZ by simultaneously granting a tax abatement through MFTE. In contrast, under Seattle’s IZ rules, to qualify for an abatement, a building must set aside additional rent-restricted units to separately meet MFTE requirements.

Washington’s tax system enables tax-shifting of abatements to avoid forgone property tax revenue

A peculiarity of Washington’s property tax system affords an important advantage for funded IZ in Washington versus many other states. To wit, funding IZ through property tax abatements could be administered so that it does not result in any forgone tax revenue.

A persistent relic of the tax rebellion era, Washington state law caps at 1 percent the annual increase in total property tax revenue that a city is allowed to collect. If a city’s tax base increases by more than 1 percent in a year, then it must reduce its tax rate such that the total revenue collected doesn’t exceed 1 percent more than the previous year.

New construction, however, is exempt from that cap. The value of new buildings gets added to the tax base, and tax revenue generated by that additional base does not count against the 1 percent cap. This includes MFTE buildings, even though they are exempt from property tax. Based on this precedent, buildings granted tax abatements through a mandatory IZ program would be treated the same way.

Ideally, a city would add the full value of new tax-exempt building to its tax base, so that the abatement would be fully tax-shifted with no forgone revenue. In that case, all property owners pay a tiny bit more to compensate for taxes not collected on the exempt new building. If applied to funded IZ, the subsidy necessary to provide affordable homes would be paid for with a slight increase in property tax across the board, just like in the case of a special levy, spread broadly across community members to support the shared priority of housing more of our neighbors.

Unfortunately, due to a quirk in the way MFTE is currently administered, typically only part of new tax-exempt building’s abatement is tax shifted, and the remainder is forgone. This split is determined by the value what been constructed on the project at the end of the year when the certificate of tax exemption is filed.

For example, according to the Seattle Office of Housing, in 2023, out of $12.5 billion in total MFTE property value, $8.8 billion was in the tax base, and $3.7 billion was not. In other words, 70 percent of the city’s MFTE abatements were tax shifted, and 30 percent was forgone. To make IZ funded with tax abatements as progressive as possible, the state can update its rules to mandate that all of a tax exempt building’s value gets added to the base, and therefore tax-shifted.

Baltimore-style policy based on real-world, changing costs is the ideal solution, but in Washington, there’s a catch

Compared with an optional program like MFTE, a mandatory IZ program demands more careful scrutiny of real estate development economics to ensure that it’s funded. If MFTE doesn’t sufficiently cover the cost of the required affordable homes, developers will opt to not use it, but at least market-rate homes will still get built. In contrast, if flawed math leads to insufficient funding of a mandatory program, cities risk losing both affordable homes and market-rate homes because developers (and their investors, who always have many other investment options) may be left with no option but to not build at all.

As described above, Baltimore adopted a smart solution for getting the math right. Baltimore’s method sidesteps a problem that plagues IZ programs across North America: uniform requirements based on upfront analysis are invariably going to end up impeding homebuilding in some cases.

Development feasibility analysis even for a single proposed building is nothing like an exact science. Generalizing the math for a one-size-fits-all IZ requirement makes it far less reliable, because it cannot account for real-world variation of building types, local market strength, and numerous other construction and operation costs that can change unpredictably over time.

That kind of inherently unreliable upfront analysis is unnecessary under Baltimore’s model, because for each building, it sets the annual tax abatement amount to match the actual forgone rent income in that building. The net income generated by the building is the same—or at least nearly as much—as what it would have been absent the IZ program with all units rented at market rates. My “nearly as much” qualifier accounts for the administrative costs of complying with the program, which also need to be covered by the tax abatement to achieve fully funded IZ.6

But here’s the catch in Washington: the state constitution requires all property to be taxed uniformly. The Baltimore system’s adjustable tax abatements would almost certainly violate this “uniformity clause.” It would be a big lift to get a constitutional amendment to fix this, but the uniformity clause is a also barrier to other progressive tax policies, such as a land value tax.

Time to lead on opportunity-rich, mixed-income communities—with funded inclusionary zoning

Funded inclusionary zoning is a hugely promising win-win solution for more rent-restricted affordable homes, and also more market-rate workforce apartments. It guarantees housing options for lower-income people in growing transit-oriented communities. And it maximizes the power of upzones to boost housing production overall, which helps keep rents under control for everyone.

To recap, funded IZ:

- Guarantees that every affected building includes affordable homes

- Avoids unfunded IZ’s backfire effect of impeding homebuilding

- Is a promising political compromise for passing legislation to legalize apartments

- Has real-world examples to model and learn from in Portland, Baltimore, and Shoreline

- Can avoid forgone property tax revenue

- Can be designed so the tax abatement remains fair even under varying market conditions

A legislative makeover of how Washington does inclusionary zoning would be a heavy political lift, no doubt. But the universally acknowledged shortage of homes in Washington demands exactly that of state leaders. The key driver of high prices and out-of-reach rents—and all the ripple effects of sprawl, pollution, and inequitable access to homeownership, wealth-building, educational excellence, jobs, and opportunity that follow—is the state’s massive housing shortage. It’s time for bold solutions that are up to the task of fixing it.

Author’s note January 28, 2025

This article has been updated to reflect new information. It incorrectly asserted that MFTE tax abatements were invariably 100 percent tax shifted. It failed to acknowledge that Baltimore’s adjustable funded IZ system would likely violate Washington’s uniformity clause. And it omitted the partially funded IZ programs in Redmond and Kirkland, Washington.