Takeaways

- Alaska can show other states what to expect when moving to nonpartisan open primaries and ranked choice voting.

- Changes include more inclusive and less partisan primary elections, more room for lawmakers to govern in less polarized ways, the elimination of the “spoiler candidate” role, and a reduced chance that candidates win elections without majority support.

- Voters will ultimately need to decide what they think is best for democracy in their state.

In 2020 Alaska led the country on election reform by adopting a combination of nonpartisan open primaries and ranked choice general elections, jettisoning its previous system of semi-closed primaries and plurality general elections.

Four years later, Alaska has more company.

Voters in multiple states, both red and blue, will decide in November whether to emulate Alaska’s system (or adopt variations) for their own elections. Montana voters are considering open primaries and mandating majority-winner elections. South Dakota voters will decide whether to open their primaries. Oregon voters will choose whether to adopt ranked choice voting for party-run primaries and general elections. Voters in Idaho and Nevada are considering an Alaska-style system of nonpartisan open primaries and allowing voters to rank candidates in general elections. And Washington, DC, is looking at allowing independents into party-controlled primaries and using ranked choice voting in general elections.

Alaska can show other states and our nation’s capital what to expect with these election reforms. Nonpartisan open primaries and ranked choice voting took effect in the state in 2022 and brought about the following changes:

- Political parties used to make the rules for primary elections. Now, laws approved by voters govern the primaries.

- Candidates popular with general election voters no longer face the prospect of “getting primaried”—i.e., losing in the primary to candidates who appeal to the smaller, often less representative pool of primary voters.

- Lawmakers have more freedom to work with colleagues of different political backgrounds on practical policy solutions without fear of electoral backlash.

- Independent candidates can now run for office under the same rules as candidates who belong to a political party rather than having to fulfill extra requirements to get on the ballot.

- Voters in the general election no longer have to worry about “wasting” their vote on a “spoiler candidate.” That is, they don’t have to vote for a candidate they’re not excited about just to keep their least-favorite candidate from winning.

- Ranked choice general elections ensure winners have the support of a majority of voters, not just more voters than any other candidate.

How Alaska’s system works: Nonpartisan open primaries and ranked choice general elections

Alaskans choose their lawmakers using a combination of nonpartisan open primaries and ranked choice general elections.

In the primary election, voters choose one favorite from a list of all the candidates. The top four candidates in each race, regardless of party affiliation, advance to the ranked choice general election.

In general election races with three or more candidates, voters rank the contenders from most to least favorite. Once the polls close, election officials count everyone’s first-choice vote. Candidates who receive a majority of the first-choice votes (more than 50 percent) win in the first round. If no candidate achieves a majority with first-choice votes alone, then the candidate with the fewest first-choice votes is eliminated. The voters who prefer the eliminated candidate have their vote for their next preference on their ballot counted. This process continues until a candidate receives majority support.

Alaska’s current system applies to the races for US House, US Senate, governor, and state legislature. The presidential election is a little different. Alaska’s Republican and Democratic parties still control the presidential primaries, but Alaska uses ranked choice voting in the general election to determine which candidate receives the state’s three electoral votes.

A then vs. now comparison: Alaska elections and politics

Below we use

a woolly mammoth emoji 🦣 for “then” conditions and

a moose emoji 🫎 for “now” conditions.

🦣 Then: The state paid for primary elections, but political parties made the rules.

🫎 Now: The state pays for primaries and runs them according to voter-approved laws.

Before Alaska switched to nonpartisan open primaries, the state funded primary elections, but the Democratic and Republican parties made the rules. They chose which voters and candidates could participate in the primaries and which candidates could identify themselves as party members on ballots and in campaigns.

Each party held a different primary election, and voters had to choose just one. Republican and independent voters could vote in the Republican primary; Democrats and those registered with third parties could not. All registered voters could vote in the Alaska Democratic Party and third parties primary.

For party stalwarts, being limited to one primary may not have been a problem. But 60 percent of Alaska voters are independents. They may have wanted to vote for a Republican in one race and a Democrat or third-party candidate in a different race, but the political parties didn’t allow it.

The primaries became more straightforward after Alaska voters approved election reforms in 2020. The state still pays for and manages the primary, but now, laws passed by voters—not rules handed down by political parties—determine how primaries work and who can participate.

In 2022 and again in 2024, Alaskans voted in a single nonpartisan open primary. All voters received the same ballot and could choose any candidate in each race. Unlike the previous system, it didn’t matter which political party the voters belonged to or whether they belonged to a party at all. Primary voters were free to vote for any candidate, regardless of political affiliation.

Alaska voters used their newfound freedom to express more complex preferences than they’d previously been allowed to show. In 2022, when all three major statewide races were on the ballot, more than half of Alaska voters split their tickets and voted for candidates of multiple parties. That means, for example, they may have chosen a Republican for governor, a Democrat for US Senate, and an independent to represent them in the state legislature. Most American voters live in states whose election systems don’t allow them to support such a varied field of candidates.

🦣 Then: Candidates who might have won a general election could lose in the primaries.

🫎 Now: Candidates with broad appeal don’t lose prematurely.

Primary elections are meant to winnow down a large field of candidates to a manageable size. But in rare but consequential cases, Alaska’s old primary election system went too far. The process sometimes eliminated candidates who had the best chance of winning in the general election, when more voters participate. And since political parties controlled and limited both who could run on their ballot and who could vote on their ballot, that smaller sliver of the electorate that tended to be more polarized than the general voting population and likelier to participate in primary elections would end up selecting which candidates advanced to the general election.

Alaska’s primary now gives voters more options. Candidates with broader appeal, often who are more moderate than the major party bases, have much better odds at making it to the general election. The system ensures that moderate Republican state legislators, such as Senators Cathy Giessel and Jesse Bjorkman and Representative Jesse Sumner, could compete in the 2022 general election rather than get eliminated in the primary. Same with US Senator Lisa Murkowski. All would likely have lost their primaries to more hardline politicians if not for ballots open to all voters and all candidates. Instead, general election voters had a chance to vet them, too, and ultimately chose them over their more polarizing opponents.

🦣 Then: Performative party politics obstructed the work of legislating.

🫎 Now: More lawmakers can work across the aisle without fearing partisan punishment.

Candidates running in Alaska’s old semi-closed partisan primary system tended to behave in a more polarized fashion both on the campaign trail and in office. They had little choice but to cater to the small number of primary voters who had a say over the candidate slate for the general election. Major-party candidates knew that if they could lock up the primary election using more partisan behavior, the lack of other options in the general would force voters into their respective camps.

Alaska’s first election using open primaries and ranked choice voting didn’t radically change the results. It did, however, remove the threat of being “primaried,” leading to a small number of moderate Republicans surviving to compete in the general, where the larger electorate chose them over more right-wing candidates. These Republicans could win without pandering to a more partisan base of voters in the primaries and therefore had the freedom to work with Democrats. The effect on the legislature was modest but meaningful. Lawmakers came closer than they would have in overturning a highly unpopular education funding veto by the governor. And they were emboldened to completely ice out legislators who prioritize party fealty over practical solutions to education, fiscal health, and other critical, but solvable, problems facing Alaska.

Bipartisanship appears to be helping in the campaign money game, too. Legislative candidates who have committed to working across the aisle have generally attracted more in 2024 campaign contributions than those who promise a more partisan approach. In the past, at least a few of these less ideological candidates likely would not have made it through the primaries.

🦣 Then: Independents had to jump through extra hoops to run for office.

🫎 Now: All candidates play by the same rules.

Before 2022, the major political parties tended to treat independents running for office as second-class candidates. The Republican party barred independents from its primaries entirely (as did Democrats) until 2018. In those years, independent candidates wanting to run in a primary had to give up their political identity by registering with the party running the primary they wanted to enter. Maintaining their independent brand meant missing out on the primaries and having to gather enough signatures to qualify for the general election ballot.

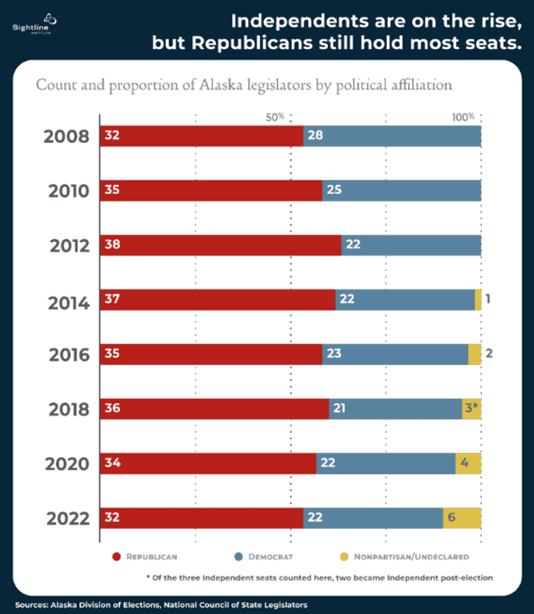

The open primaries leveled the playing field for independent candidates. Now all candidates of all political affiliations run on a standard ballot accessible to all voters. The lowered barriers for candidates and voters outside the major parties appear to be the likeliest explanation for why more independents serve in the Alaska legislature today than at any point in the state’s history. In addition, the statewide candidates who won in 2022 in aggregate represent Alaska’s independent/Republican-leaning politics: a conservative governor, a moderate Republican US senator, and a moderate Democrat in the US House. Well over half of Alaska voters are independents, and the expanded opportunities for independent candidates provides them with better representation.

🦣 Then: Elections were vulnerable to the “spoiler effect.”

🫎 Now: Ranked choice voting eliminates spoiled elections.

In America’s two-party plurality-winner system, the existence of a third candidate creates concern that they will swing the election unfairly. A third candidate can siphon off votes from a candidate who would have won otherwise. This fear of third parties ensures that the increasingly polarized worldviews of the two-party majority continue to dominate US politics.

Take Alaska’s 1994 gubernatorial election. Democrat Tony Knowles won with just 41 percent of the vote. The rest of the vote was split between the remaining candidates. The Republican in the race, Jim Campbell, was fewer than 600 votes behind. A third candidate, Jack Coghill of the Alaska Independence Party, attracted nearly 28,000 votes. Had Coghill’s supporters been allowed to name their second choice, Campbell may well have won. But they weren’t allowed to do that under the old system.

“You’d never have had Tony Knowles as governor,” Anchorage pollster and consultant Ivan Moore told the Alaska Beacon. Similarly, the results of other high-profile races in Alaska history point strongly to spoiler candidates changing the outcome.

The prospect of spoiling an election and allowing a candidate they despise to win office often leads voters to choose a “meh” major-party candidate over a third-party or independent candidate they truly prefer. And on the candidate side, third-party and other candidates face the prospect of being the spoiler, which can be especially discouraging when you’re already trying to compete against the major parties.

In Alaska, candidates of all political backgrounds can now run in ranked choice elections without worrying about diverting votes from more mainstream candidates. Voters have less cause to worry about “wasting” their votes by supporting these candidates. If less popular candidates are eliminated, votes they received can be reallocated to voters’ second and third choices.

Including independent and third-party candidates in the race, even if they don’t win, can broaden the debate and bring attention to issues that would otherwise be ignored. And because voters can choose them without fearing the results, Alaskans have more insight into how much support independents and third parties really have.

🦣 Then: Candidates could win without support from a majority of voters.

🫎 Now: Ranked choice voting makes majority winners more likely.

Between 2012 and 2020, 12 elections in Alaska resulted in candidates winning with support from less than half of voters. That included the 2014 governor’s and US Senate races, the 2016 US Senate race, and nine state legislative races.

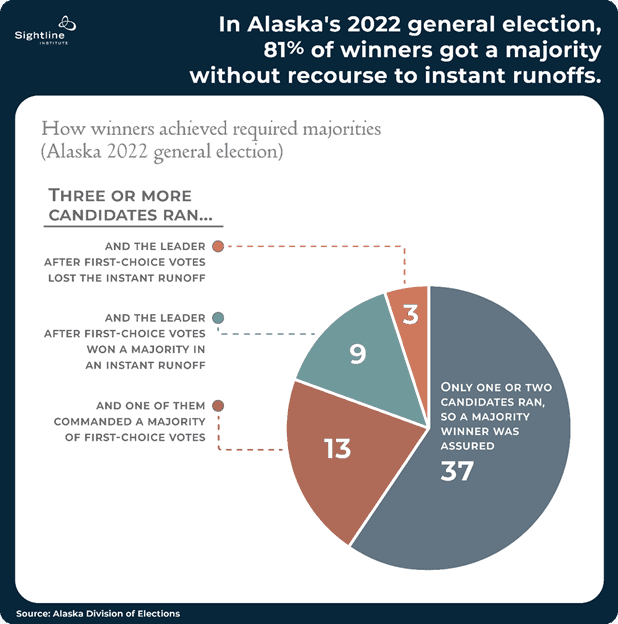

Today ranked choice voting allows for an “instant runoff” between the top candidates until one receives more than half the votes in the final round. In 2022 a majority winner emerged without the need for an instant runoff in 81 percent of general election races.

For example, in the 62 races on the ballot in Alaska’s 2022 general election, only 12 required ranked choice to identify the majority winner. Some 37 races only attracted one or two candidates, which all but guaranteed that one candidate would receive a majority of first-choice votes.

Another 13 Alaska races that year attracted three or four candidates, but one candidate still commanded a majority of first-choice votes. Consequently, ranked choice didn’t apply to those races. Among the remaining 12, where ranked choice came into play, nine of the races went to whoever led after the tally of first choices.

🦣 Then: Alaska is voting on election reform

🫎 Now: Alaska is voting on election reform

While voters in several states and Washington, DC, are deciding whether to adopt Alaska-style election reforms in November 2024, Alaska voters will decide whether to keep theirs in place. Though the issue has become more partisan in recent years, it is not an inherently partisan issue. In 2020, when Alaskans were weighing the adoption of the system, the typical partisan signaling was garbled because the camps supporting and opposing the initiative were unusually bipartisan.

There is no easy partisan shortcut for deciding whether to support or oppose nonpartisan open primaries or ranked choice voting. The decision will require some self-reflection on the part of voters across multiple states on how they believe a democracy should function. Voters might approach the question by making a list of election norms they believe are essential to a strong democracy. Then, ask themselves which system they believe would uphold these democratic values more effectively.

Correction: The article originally said Washington, DC, was also considering adopting an Alaska-style open primary. Washington, DC, is in fact voting on whether to allow independents into primary elections, but, unlike Alaska, would retain party-controlled primaries.