Takeaways

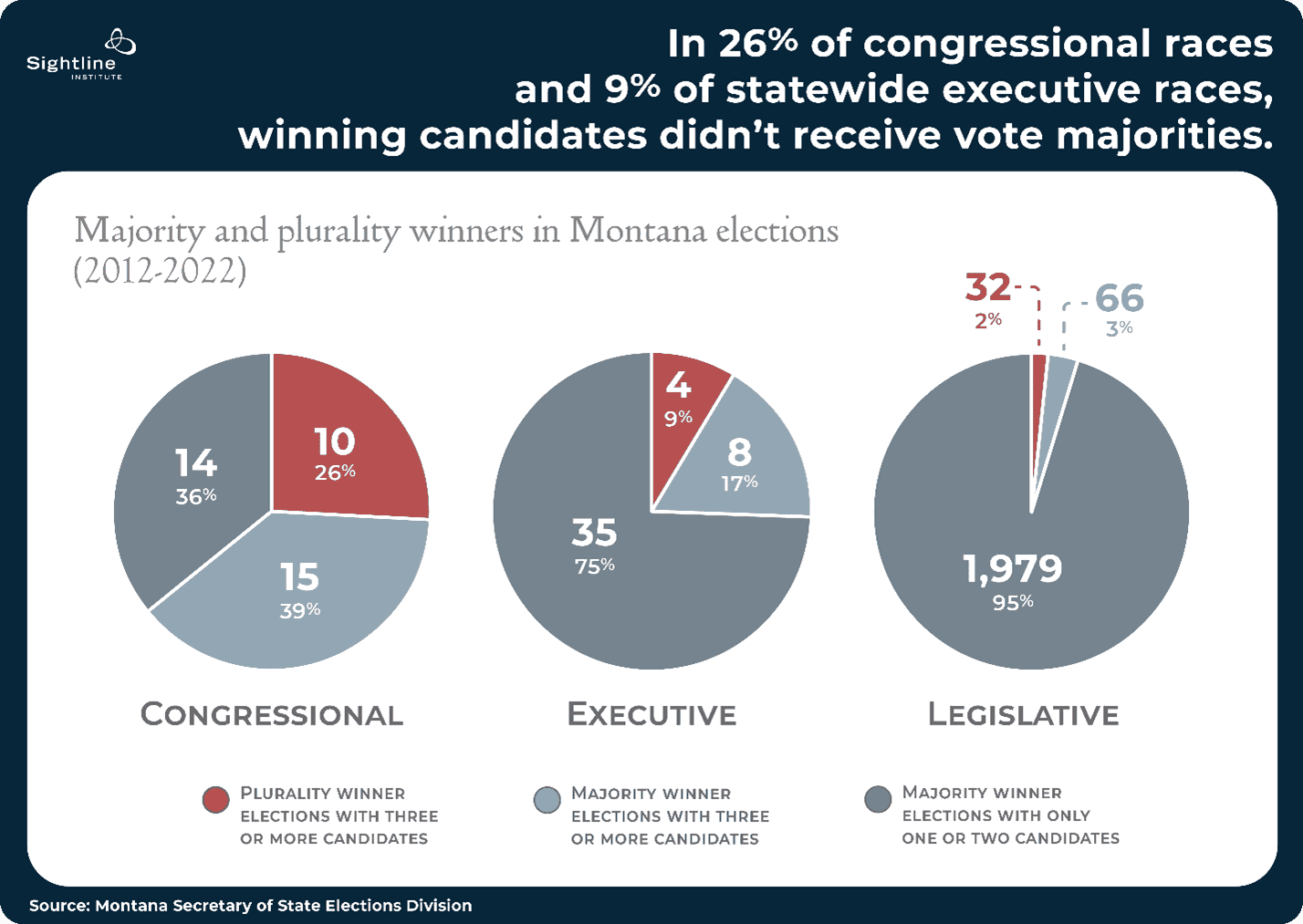

- Though most winners in Montana elections command a majority of votes, plurality winners (who have more votes than other candidates but less than 50 percent) emerged in 26 percent of congressional elections and 9 percent of statewide elections from 2012 to 2022.

- If a majority of voters support other candidates, plurality winners may inaccurately represent voter preferences.

- The potential for candidates to win without majority support gives the major parties an incentive to surreptitiously support third-party spoilers.

- Partisan primaries also have a plurality winner problem: candidates who command only pluralities in their party primaries commonly perform worse in the general election than do candidates who win their primaries with majority support.

- Ballot measures CI-126 and CI-127 on Montana’s ballot this November would enact policies to address these issues.

As in most elections, Montanans have a lot of important priorities to consider this November. One contest in particular, though, is receiving outsized attention: control of the US Senate may hinge on the outcome of the race between incumbent Democrat Jon Tester and Republican Tim Sheehy. In this race, two other candidates are drawing the attention (and ire) of the major parties. Earlier in 2024, the Montana Democratic Party lost a lawsuit to remove Green Party candidate Robert Barb from the US Senate ballot. And former president Donald Trump personally put pressure on Libertarian nominee Sid Daoud to drop out of the race and endorse Sheehy.

Partisan jockeying over candidates with virtually no chance of winning is not uncommon in the United States and should be familiar to longtime observers of Montana politics. The more competitive a race, the more third-party candidates matter. Partisan primaries present a similar problem: crowded fields of candidates can split the vote, sending a nominee with minority support from their own party to the general election.

In 46 primary and general election contests from 2012 to 2022, state and federal officeholders in Montana won only plurality support (more votes than any other candidate but less than 50 percent of the vote). In other words, a majority of voters preferred other candidates to the actual winner.

The plurality winner problem conflicts with the principle of majority rule, a core tenet of democracy. It also encourages the major parties to amplify divisions among voters and spend valuable resources propping up or undermining minor-party candidates to spoil an election for their competitors.

Other states, including Alaska, Georgia, Maine, and Mississippi, have implemented systems that guarantee majority-winner elections. Two measures on November’s ballot would do the same in Montana.

Montana plurality winners by the numbers

Sightline examined more than 2,000 Montana elections between 2012 and 2022, including all statewide races for governor, lieutenant governor, attorney general, secretary of state, state auditor, and superintendent of public instruction, along with senators and representatives at the state and federal levels.1 Altogether, the inquiry covered 2,163 races (780 general elections and 1,383 partisan primaries) over the decade. It revealed that:

- In 94 percent of races, only one or two candidates were on the ballot, guaranteeing a majority winner.

- Multicandidate races are most common at the congressional and statewide levels, as more than half of Montana’s congressional races from 2012 to 2022 had three or more candidates.

- Few state legislative contests attract more than two candidates, as plurality winners prevailed in only 2 percent of the 2,077 elections for state house and state senate.

- However, some of the most consequential state and federal general election contests produced plurality winners, with winning candidates receiving less than 50 percent of the vote in elections for US Senate (2012), Montana governor and lieutenant governor (2012), and US House (2017 and 2022).

- In ten partisan primaries for statewide or congressional offices, nominees who did not have majority support from their own party moved on to the general election.

- All told, a majority of voters cast their ballots for someone other than the winning candidate in 26 percent of congressional races and 9 percent of statewide races.

The majority of Montana elections produce majority winners. But plurality winners are most common in high-profile, high-impact statewide and congressional contests.

Notable among the plurality-winner contests were Democratic US Senator Jon Tester’s general election in 2012 and Republican US Representative Ryan Zinke’s bid for Montana’s First Congressional District in 2022. In both instances, a majority of voters split their vote between the nominee of the opposite major party and the Libertarian candidate.

In such cases, it isn’t clear if a majority of voters preferred the person who took office. If the races had been conducted with a majority-winner requirement, such as a runoff election, the outcome could have been different—and the electorate’s views better represented.

In general elections, major parties play up the spoiler effect

Americans tell pollsters they are deeply dissatisfied with the two-party system. Few voters can stomach “throwing away” their votes on a candidate with virtually no chance of winning, despite survey respondents showing an appetite for major-party alternatives. Yet third-party and independent candidates frequently contest high-profile races against slim odds, attracting small but dedicated bases.

Republicans and Democrats can adjust their policies and rhetoric to win over voters who might be inclined to vote for minor-party candidates. But in practice, the dominant parties also dedicate resources and energy to removing potential “spoilers” from the ballot, and party supporters do their best to amplify the spoiler effect at the other party’s expense.

In Montana, Republicans supported 2020 ballot access efforts for the left-wing Green Party, hoping to drain support from the Democratic Party. And in the 2012 US Senate election, Tester’s liberal supporters boosted the right-leaning Libertarian candidate, who ultimately won almost 32,000 votes in an election decided by just over 18,000, arguably subtracting most of those votes from the Republican tally.

In the state legislature, parties are likely less inclined to recruit or support potential spoilers due to the low chance of flipping control of the legislative branch, where Republicans have held a multi-seat majority in both chambers since 2011. But a change in control of just a few districts can still shift state policy.

As of October 2024, the Republican supermajority can send state constitutional amendments to the ballot with no support from the minority party, because they hold two-thirds of the seats in each legislative chamber. To block such measures, Democrats would need to flip only one state senate seat or three state house seats. So although many seats are not competitive, plurality winners in a few races could change the dynamics of governing in Montana.

The current pick-one plurality winner system dominated by Democrats and Republicans puts voters in an unnecessary bind, discouraging Montanans from voting their true preferences. And the two major parties shift the spotlight away from policy and the will of voters by engaging in high-stakes expensive and time-consuming tugs-of-war over what it takes to get third-party and independent candidates on the ballot.

Primaries amplify division

The plurality winner problem is not limited to the general election. In primary elections, pick-one voting encourages candidates to tear down competitors who have similar platforms. Campaigns can stand out by focusing on personal attacks and inflammatory rhetoric rather than policy or common goals. And sometimes divisions are pronounced enough that a party’s nominee fails to gain the support of a majority of party voters.

Take for example the Democratic primary for Montana’s at-large congressional district in 2012. Kim Gillan won only 31 percent of the vote in a seven-candidate field; more than two-thirds of Democrats in that year’s primary preferred other candidates.

Though many plurality primary winners do go on to win general elections, research indicates that they perform worse overall than candidates who win majority support from their party’s voters. A working paper on congressional races between 2012 and 2022 demonstrates that plurality primary winners performed 1.5 percentage points worse in the general election than the district’s overall partisanship. (So in a 53 percent Democratic or Republican district, a plurality primary winner would receive only 51.5 percent of the total vote.)

In tight congressional, legislative, and statewide elections, a small margin can be more than enough to change the outcome. Low-performing primary winners will remain at an amplified risk of a narrow loss as long as the pick-one general election system (which is also susceptible to plurality outcomes due to a crowded field of candidates) remains in place.

Montana can avoid these distortions in future elections

Without changes to Montana’s voting methods, the spoiler effect will continue to bedevil races in Big Sky Country. But other states have developed solutions to the plurality winner problem, ensuring that key offices are elected with majority support.

Georgia and Mississippi hold delayed runoff elections between the two most popular candidates if no candidate manages to clear the 50 percent mark in the general. And Alaska and Maine use instant runoffs in which voters indicate their second- and third-choice candidates so that officials can conduct a runoff without the costs of holding a second election.

Two election-related Montana ballot measures this November aim to address these distortions:

CI-126 would establish top-four open primaries for statewide offices (such as governor), congressional races, and state legislators. All candidates would run on one ballot, regardless of party, and the primary would be open to all voters, just like the general election. The top four vote-getters would move on to the general election. This would solve the issue of a single winner dividing the field and would allow all Montanans to weigh in on the primary vote, which would likely lead to higher turnout and a candidate pool that more closely reflects the values of the voters.

CI-127 would require that all election winners receive a majority of the vote. If the measure passes, the legislature will have to implement a runoff mechanism to remedy the small number of elections in which no candidate wins a majority. Whether that means a second runoff election a few weeks after the first (as in Georgia and Mississippi) or an instant runoff using ranked choice voting (as in Alaska and Maine) is yet to be determined, but legislators have no shortage of tested and proven solutions to choose from. (For more information on the majority vote requirement and implementation, see this fact sheet.)

Plurality winner elections are not the norm in Montana. Only 2 percent of legislative races, 9 percent of statewide executive races, and 26 percent of congressional races from 2012 to 2022 produced winners without majority support, but individual elections can have profound impacts on policy outcomes.

Majority vote requirements and open primaries would change systems that, according to our analysis, currently encourage Democratic and Republican candidates in Montana to run exclusionary, divisive primaries and manipulate minor parties to spoil their rivals’ elections. If Alaska and other states are a guide, the switch would place more campaign focus on appealing platforms and consensus-building and less on personal attacks and political gamesmanship.