Takeaways

- The Northwest needs a lot more electric transmission capacity to meet rising power demand without burning coal or gas. But building new transmission lines can take decades and cost billions.

- Reconductoring—upgrading the wires on transmission lines—is an underdeployed solution that can save money and time while boosting capacity.

- In the Northwest, up to 23,000 miles of transmission lines (about 40 percent of the region’s grid) could be suitable for reconductoring.

- To get more of these no-brainer wire upgrade projects off the ground, policymakers can require utilities to evaluate them, fast-track permitting, and introduce performance incentives.

Find audio versions of Sightline articles on any of your favorite podcast platforms, including Spotify, YouTube, and Apple.

The lights could soon dim on the Northwest’s climate goals unless the electric grid gets some serious TLC.

The region, like the United States as a whole, needs more electric transmission capacity to reach the best wind and solar resources and meet rising power demand without burning coal or gas. But building new transmission lines can take decades and cost billions. Luckily there are no-brainer ways to squeeze more juice out of the existing electric grid.

Among the options, reconductoring—swapping out the wires on transmission lines for higher capacity ones—holds particular promise for its relative speed to deployment, capacity potential, and cost.1

Reconductoring can more than double a line’s capacity, costs less than half the price of building a brand-new line, and can take just 18 to 36 months to implement.

In the Northwest, up to 23,000 miles of transmission lines (about 40 percent of the region’s electric grid) could be suitable for reconductoring.2 To get more wire upgrade projects off the ground, policymakers can improve utility planning processes, fast-track permitting, and introduce performance incentives. With most of the region’s grid strung up with wires invented more than 100 years ago, a grid glow-up is long overdue.

Reconductoring can double transmission lines’ capacity for less than half the cost of building new lines

Why should people who care about climate change pay attention to wires? Here’s a quick primer: In sum, the type of wire—conductor—on a transmission line affects how much power it can carry, how much electricity it wastes, and how much it sags. (Sagging lines can spark wildfires.) Swapping out old wires with the latest and greatest technology is far cheaper, faster, and easier than building whole new transmission lines.

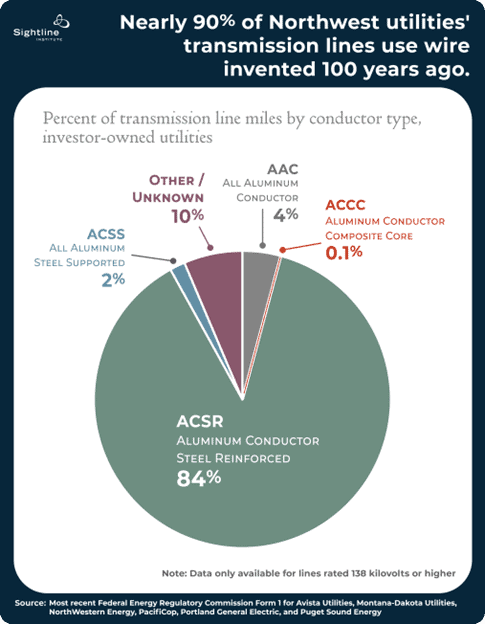

For more than 100 years, transmission owners have strung up the same type of wire. Aluminum conductor steel reinforced (ACSR), as it is known, remains the default conductor for most transmission projects in the United States.

In the Northwest, nearly all investor-owned utilities’ transmission lines are outfitted with ACSR, as Figure 1 shows. (Bonneville Power Administration [BPA], which owns and operates most of the region’s high-voltage transmission system, does not provide detailed data about conductor type. However, the vast majority of its lines use ACSR, according to a BPA representative.)

Figure 1.

In the 1970s, the industry introduced a new type of conductor known as aluminum conductor steel supported (ACSS). ACSS conductors nearly double the capacity of their ACSR counterparts, but they come with a big downside: excessive sagging at high temperatures. Sag is a particular concern in wildfire-prone areas like the Northwest. Reconductoring with ACSS conductors can require raising structures or placing more towers closer together to meet minimum clearance standards, which increases project costs.

In the 2000s, newer, more advanced conductors entered the market, which traded out the traditional steel core for a smaller composite of glass, ceramic, or carbon fibers. This new lighter core allowed more aluminum (which conducts electricity) to fit on a wire of equal diameter, making it possible to operate the line at a higher temperature. Higher operating temperatures increase a line’s thermal limit—one of three possible limits to transmission lines’ capacity.

The most promising and widely deployed composite-core conductor is known as aluminum conductor composite core (ACCC®). (ACSS trapezoidal wire [ACSS/TW], a more advanced ACSS model, was also introduced in the 2000s.)

Here’s an analogy to explain this that will make sense to anyone born before the 2000s, at least: If ACSR conductors are dial-up internet, ACCC® conductors are 5G. ACCC® conductors double the capacity of ACSR models. They don’t sag at high temperatures, and they’re the most efficient conductors on the market, meaning less electricity is lost when zapped from point A to point B.

The main downside of ACCC® conductors is cost; they can be twice or three times as expensive as ACSR wires. (Table 1 below compares key attributes of ACSR, ACSS, ACSS/TW, and ACCC® conductors.)

Table 1. Comparison of common conductor types

| Name | Year invented | Capacity increase over ACSR | Higher sag than ACSR? | Efficiency increase over ACSR at 20°C | Unit cost increase over ACSR |

| ACSR aluminum conductor steel reinforced | 1900s | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| ACSS aluminum conductor steel supported | 1970s | <1.7x | Yes, at max temperature | ~1.03x | ~1.1x |

| ACSS/TW ACSS trapezoidal wire | 2000s | <2.1x | Yes, at max temperature | ~1.18–1.2x | ~1.3–1.5x |

| ACCC® aluminum conductor composite core | 2000s | ~2x | No | ~1.2x | ~2–3x |

Source: 2035 and Beyond: Reconductoring and Advanced Reconductors Scan Report (December 2023).

Note: See source reports for more detailed comparisons of all conductor types.

However, the cost of reconductoring, even with advanced conductors such as ACCC®, is still less than half that of building new lines with traditional, cheaper ACSR conductors. That’s because the cost of conductors makes up a small portion of the overall cost of building a transmission line. Most of the bill comes from erecting towers and acquiring new rights-of-way, neither of which is necessary when simply replacing wires. Reconductoring with composite-core conductors is sort of like upgrading your kitchen with state-of-the-art appliances; it’s pricey but far cheaper than buying a new house.

Few Northwest utilities use advanced conductors

The opportunities for modernizing the electric grid are considerable. In the Northwest, composite-core conductors (the latest and greatest) are virtually nonexistent. Only NorthWestern Energy, one of Montana’s utilities, has reconductored a line using an ACCC® conductor. A new line that PacifiCorp completed in Oregon in 2023 is the only other one in the region that uses an ACCC® conductor, according to Sightline’s analysis, and that line is four miles long.3

BPA is advancing several reconductoring projects but is only considering using ACSS or larger ACSR conductors, not ACCC® ones, according to an agency spokesperson.

Inertia and caution can largely explain utilities’ and BPA’s slow adoption of composite-core conductors. Installing advanced conductors requires training workers and building confidence in a technology different than the one companies have relied on for more than a century. In 2019 a contract worker for Avista Utilities died working on a transmission line project. Two representatives from Northwest transmission-owning entities told Sightline the project involved a composite-core conductor and cited it as a reason their companies are wary of the technology, though neither were sure if the conductor type had contributed to the accident. “We have not gone through the testing to trust the composite conductors,” one told Sightline. However, according to a representative of CTC Global, which manufactures ACCC®, the accident occurred on a project using a different type of conductor, not ACCC®. (Sightline was unable to find public information about the type of conductor used).

Still, utilities in more than 60 countries have now used ACCC® conductors in over 1,000 projects. In fact, Belgium plans to reconductor its entire high-voltage transmission backbone system by 2035, in part with ACCC® conductors.

Up to 40 percent of the Northwest’s electric grid could be suitable for reconductoring

Despite recent hype, not all lines are good candidates for reconductoring. To state the obvious, only lines with a (current or future) capacity constraint benefit from a capacity upgrade. To state the less obvious, that capacity constraint needs to be specifically caused by a thermal limit for reconductoring to be useful.4 Lines with voltage ratings less than or equal to 345 kilovolts (kV) and shorter than 50 miles are the most likely to be thermally limited—and thus good reconductoring candidates.

Roughly 23,000 miles of transmission lines in the Northwest meet these voltage and length criteria, representing about 40 percent of the region’s grid. Table 2 below provides an estimate of how many miles of transmission lines in each Northwest state are rated 345 kV or lower and shorter than 50 miles.

Table 2. Miles of transmission lines potentially suitable for reconductoring in Northwest states

| Short line miles (345 kV and under and shorter than 50 miles) | Total line miles | Percentage, short line miles | |

| Idaho | 4,403 | 10,826 | 41% |

| Montana | 5,822 | 13,991 | 42% |

| Oregon | 5,523 | 14,639 | 38% |

| Washington | 6,861 | 16,807 | 41% |

| Total | 22,609 | 56,263 | 40% |

Source: Data provided to Sightline by Idaho National Laboratory (INL). INL’s methodology and data for other regions can be found in the Advanced Conductor Scan Report.

However, many of these transmission wires likely rest on aging structures that companies would need to fully rebuild if they were to reconductor. “Some of our structures are 80 years old. We don’t want to hang new wire on an old structure that we then have to replace,” a BPA representative told Sightline. (In the case of a full rebuild, companies are more likely to install larger traditional ACSR conductors or ACSS models than the more expensive newer composite-core conductors, according to all the Northwest utility representatives Sightline spoke to.)

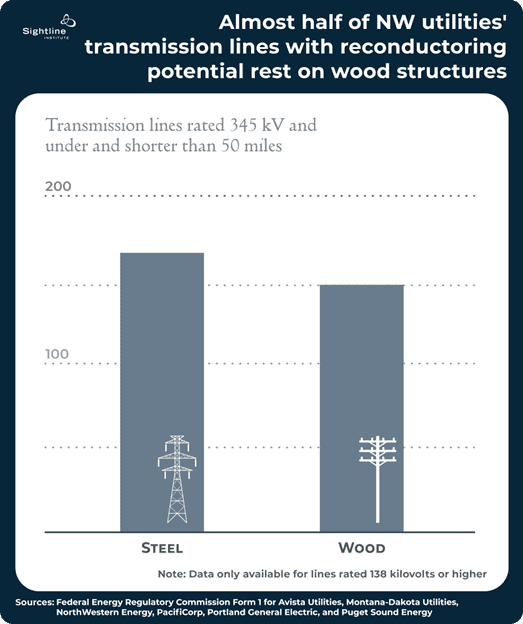

Roughly half of Northwest investor-owned utilities’ transmission lines rated 345 kV and under and shorter than 50 miles rest on wood structures, as Figure 2 shows. (BPA does not release detailed data about the structure types of its lines.) Any reconductoring project on these lines would likely require a full rebuild. Still, rebuilds are cheaper, faster, and easier than brand-new greenfield transmission lines, even if not as simple as just reconductoring.

Even so, reconductoring or rebuilding existing lines alone cannot decarbonize the Northwest. Reconductoring is like upgrading a regular bus to a double-decker one: the new bus can carry twice as many people but it’s still taking them to the same places it always has. The Northwest needs not only more grid capacity but also new grid routes to reach the best wind and solar resources. “Central Washington is where solar and wind projects want to be located,” one utility representative explained. “We don’t have much transmission there to rebuild.”

Northwest leaders can plug policy gaps to modernize wires

Reconductoring costs less than building new power lines and packs a big capacity punch, so what’s standing in the way of more of these projects? The “Three P” barriers to new transmission lines—Planning, Permitting, and Paying for—also apply to reconductoring projects. Policy interventions on each can help spur more upgrade projects:

- Better planning: Ask utilities to assess reconductoring’s potential.

- Speedier permitting: Exempt reconductoring projects from environmental review.

- Smarter paying: Incentivize reconductoring through performance-based regulation (PBR).

Below is Sightline’s inventory of the policies that are already in place in the Northwest and the remaining gaps. (See the appendix for a table version of this information.)

Planning: Ask utilities to identify reconductoring candidates

No state in the Northwest requires utilities to assess the potential for reconductoring. But regulators in both Oregon and Washington could reasonably interpret statutes governing utility planning processes to do so.

Washington asks utilities to “identify any need to develop new, or expand or upgrade existing, bulk transmission and distribution facilities” and to “make more effective use of existing transmission capacity.” Oregon’s guidelines for utility planning state that utilities must investigate “all known resources for meeting the utility’s load…including supply-side options which focus on the generation, purchase and transmission of power.” Reconductoring is one way that utilities can meet growing loads.

Still, Northwest policymakers wanting to ensure that utilities don’t overlook reconductoring could take inspiration from California’s Senate Bill 1006. The bill would require utilities to “prepare a study of which of its transmission lines can be reconductored with advanced conductors.”5 It would not only ensure that utilities evaluate reconductoring but also guarantee that companies give adequate consideration to modern, efficient technology.

State-level planning would complement recent developments at the regional level. The Western Transmission Expansion Coalition (WestTEC), the new transmission planning effort that includes the Northwest, will evaluate reconductoring, including with advanced conductors, in the 20-year plan it is developing. Plus, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission’s (FERC) landmark May 2024 transmission planning order mandates that transmission providers analyze advanced conductors when evaluating upgrades to existing lines. This order may lead more utilities to explore newer wire types when reconductoring.

Permitting: Fast-track reconductoring and rebuild projects

The environmental impact of swapping out wires on existing structures or putting new structures where structures already exist is next to none. As a result, some jurisdictions have exempted reconductoring and rebuild projects from permitting processes.

Thanks to Nan & Bill Noble for supporting a sustainable Cascadia.

Our work is made possible by the generosity of people like you.

In May 2024, the US Department of Energy (DOE) expanded an existing National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) categorical exclusion to apply to more reconductoring and rebuild projects.6 The new rule removes an earlier limit to the length of lines that qualify for the exclusion. It also specifies that the exclusion applies to upgrade or rebuild projects that widen existing rights-of-way so long as the widening is on “previously disturbed lands.” In the Northwest this rule could especially ease the way for BPA to pursue more reconductoring or rebuild projects; since BPA is a federal agency, all its transmission projects are subject to NEPA.

Among Northwest states, Montana is the only one to exempt all capacity upgrades to existing transmission lines from its environmental review. (Idaho has no state-level permitting process for transmission lines.)

In Oregon, large transmission lines (those rated 230 kV or higher, stretch longer than 10 miles, and cross multiple cities or counties) fall under the jurisdiction of the Energy Facility Siting Council (EFSC), the state’s permitting agency. Any facility under EFSC’s jurisdiction must comply with a set of Oregon-specific environmental and other standards to proceed. However, EFSC has exempted reconductoring projects on lines rated 230 kV and above from needing review based on its interpretation of state statute.7

Even so, reconductoring or rebuild projects that are exempt from EFSC review could still have to go through “a litany” of local permitting processes that can conflict, a utility representative explained. Oregon could create an expedited approval process for all reconductoring and rebuild projects to resolve confusion and fast-track these no-brainer projects.

Washington lawmakers can also ease permitting processes for electric grid upgrades. The state only spares some reconductoring and rebuild projects from review under the State Environmental Policy Act (SEPA). Projects on lines rated 115 kV or less and within existing rights-of-way are exempt. Policymakers could remove these voltage limits and broaden the exemption to apply to projects that widen existing rights-of-way on previously disturbed lands, following the US DOE’s lead.

And as in Oregon, projects exempt from Washington’s state-level review can still face local permitting challenges without a more comprehensive expedited approval path. “If it’s not maintenance, you trigger permitting,” one utility representative explained, adding that he’d like to see exemptions for all “new wires and new poles [that stay] right where they’re already at.”

Paying: Incentivize upgrades with PBR

Finally, policymakers and regulators could financially incentivize utilities to reconductor, but they would be smart to proceed cautiously. Utilities already profit when they reconductor lines, since these projects are capital expenditures (and low-risk ones at that). Plus, not all lines are good candidates for reconductoring, nor can upgrading all lines help with decarbonization goals. Offering too-generous financial incentives risks enticing a utility to “gold plate” its system.

A 2023 Montana law attempts to incentivize advanced conductors for both reconductoring and new lines.8

The law allows regulators to develop cost-effectiveness criteria, which could include “decreased electrical losses” for projects using advanced conductors and to put projects meeting those criteria into the utility’s rate base. The Montana law, though, goes a step too far by then allowing utilities to earn a higher-than-normal rate of return on these low-risk projects.

Nonetheless, the cost-effectiveness provision of Montana’s law is a worthy idea. It resembles a step toward regulation to steer specific outcomes, also known as performance-based regulation (PBR). PBR revises traditional utility incentives, which encourage companies to increase infrastructure spending and sales even when these pursuits are at odds with societal goals such as energy conservation. PBR instead measures, rewards, or penalizes utilities’ performance using values-aligned metrics such as reductions in greenhouse gas emissions or customer savings.9

Washington is the only state in the Northwest so far fully transitioning to PBR. (Oregon investigated PBR in 2018, but those efforts have stalled.) Regulators at Washington State’s Utilities and Transportation Commission (UTC) are developing performance metrics but do not plan to immediately tie them to any financial reward or penalty. So far, the UTC has declined to include any metrics related to grid upgrades.

None of these incentives would apply to BPA, however, since, as a federal agency, it is not state regulated. But the upcoming Northwest Power Plan, which the Northwest Power and Conservation Council will kick off in 2025, could encourage BPA to pursue more reconductoring projects. The 1980 Northwest Power Act requires BPA to conserve and acquire new resources in a way that is consistent with the Northwest Power Plan. The 2010 and 2016 Power Plans included reconductoring as an energy efficiency strategy. The Council would be smart to devote renewed attention to reconductoring in its newest plan, especially given advances in conductor technology and the ever-mounting difficulty building greenfield lines.

Squeezing more juice out of the existing electric grid

Increasing the Northwest’s electric grid capacity is getting more urgent by the day. Thankfully the existing grid has more to give. Replacing old wires with newer, higher-capacity ones is a walk in the park compared to building new transmission lines. Policymakers would be smart to remove any lingering impediments to these projects—and brighten the region’s chances of meeting its climate goals.

Appendix: Northwest States’ Reconductoring Policies

| Idaho | Montana | Oregon | Washington | |

| Better planning Ask utilities to assess reconductoring’s potential | No. | No. | Not explicitly. The Oregon Public Utilities Commission could interpret Order No. 07-002 as requiring utilities to evaluate reconductoring. | Not explicitly. The Washington Utilities and Transportation Commission could interpret SB 5165 as requiring utilities to evaluate reconductoring. |

| Speedier permitting Exempt reconductoring projects from environmental review | n/a. Idaho has no state-level permitting process. | Yes. Montana exempts all reconductoring projects from state environmental review. | Only for some lines. The Energy Facility Siting Council (EFSC) interprets ORS 469.300 as exempting reconductoring/rebuild projects on lines with voltages 230 kV and greater from needing an EFSC site certificate. However, lines may still need to go through local permitting processes. | Only for some lines. WAC 197-11-800 exempts reconductoring/rebuild projects on lines with voltages 115 kV or under, within existing rights-of-way, from review under the State Environmental Policy Act (SEPA). Lines may still need to go through local permitting processes. |

| Smarter paying Incentivize reconductoring through performance-based regulation (PBR) | No. | No, but allows incentives for advanced conductors. 2024 Montana law grants a 2 percent adder to projects using an advanced conductor that meet cost-effectiveness criteria. | No. Oregon has studied PBR but not adopted it. | Not yet. Washington is developing a PBR framework but has not yet included a metric incentivizing reconductoring. |