Takeaways

Ranked choice voting is a method that can be implemented in many types of elections across a variety of jurisdictions, depending on local election laws.

In the Pacific Northwest, ranked choice voting is used:

- In the general election after a unified, nonpartisan open primary in Alaska

- In the general election without a primary in Corvallis, Benton County, and upcoming in Portland, Oregon

- Upcoming in the nonpartisan open primary followed by a top-two general election in Seattle

- Potentially in the general election and closed party primaries in Oregon (currently used this way in Maine)

Ranked choice voting has similar benefits when applied to various types of elections: The method ensures a winner that a majority of voters choose; prevents spoiler candidates from warping election outcomes; punishes negative campaigning; and encourages more diverse and less established candidates to run.

Find audio versions of Sightline articles on any of your favorite podcast platforms, including Spotify, Google, and Apple.

General elections in Alaska. Closed party primaries and the general election in Maine. Certain party primaries in New York City and Virginia. City offices in Minneapolis and San Francisco. Military and overseas voters in Alabama and Arkansas. Ranked choice voting applies in all these varied contexts—and many more!

In 2024, however, millions of US voters will choose their leaders using the method known as plurality voting. Plurality voting is still the most common voting method in the US, even though it doesn’t always foster the best outcomes for the majority of voters: unpopular or extreme candidates can win with less than majority support and personal attacks work better than discussion of issues, on the campaign trail through to the halls of power.

Multiple cities, states, and other governing bodies have sought out and demonstrated another way: ranked choice voting.

Ranked choice voting is simple. In trials and testing in advanced democracies throughout the world, the method has evinced benefits in partisan primaries, nonpartisan general elections, and others: it ensures that winners have the support of a majority of voters,1prevents spoiler candidates from warping election outcomes, punishes negative campaigning, and encourages more diverse and less established candidates to jump in and run for office.

It’s also adaptable. The variations in our numerous elections in the US mean that ranked choice voting can and has been used in a large variety of contexts: sometimes for local offices, sometimes just in presidential primaries, sometimes only in a general election.

As more and more states and localities look to adopt ranked choice voting, Sightline is here to walk you through how different voting methods can combine with different types of elections, with a focus on specific scenarios here in Cascadia. Voting methods include plurality voting (currently used in most US elections), ranked choice voting, and many others that Sightline has previously described in detail. Types of elections include general elections, runoffs, and primaries, the last of which can be further classified into nonpartisan or partisan, closed, open, or some blend.

This article will cover single-winner elections—executive offices like mayor or president. For more on multi-winner, proportional elections and legislative bodies, see Sightline’s evergreen glossary for electing legislative bodies.

As a “field guide,” this piece is longer than some of Sightline’s articles and is intended as a reference. If you’d like, you can skip to the explainers of regional scenarios.

Voting Methods: Plurality and Ranked Choice

Plurality voting: The status quo in most US elections

Many US elections determine winners through plurality voting. With plurality voting, also called “first-past-the-post” or “winner-take-all,” each voter votes for one candidate. The candidate with the most votes wins, even if they only won a plurality (more than any other candidate) and not a majority (more than half) of the votes.

This method can lead to unrepresentative outcomes when there are more than two people running. If three candidates are competing for one position, they might all split the vote and the winner could be elected with as little as 34 percent of the vote. That means that fully two-thirds of the electorate wanted someone else in the office instead! With more candidates in the field, a winner might earn even less support.

Spoiler candidates have shown up in plurality elections time and time again. One of the best-known national examples is when votes for Ralph Nader in 2000 outnumbered the margin that Al Gore needed to win in key battleground states, allowing George W. Bush to win the US presidency even though Nader and Gore had more similar positions and a higher combined vote total.

There are plenty of regional examples, too: in Montana in 2012, Democratic Senator Jon Tester won reelection with just over 18,000 votes more than the Republican candidate—but a libertarian in the race pulled almost 32,000 votes, likely spoiling the election for the Republican. Similar scenarios have peppered Cascadia’s history, affecting both major parties, from gubernatorial races in Oregon to primaries in Washington state.

Ranked choice voting: Gradually expanding across the US, offering more choice to voters

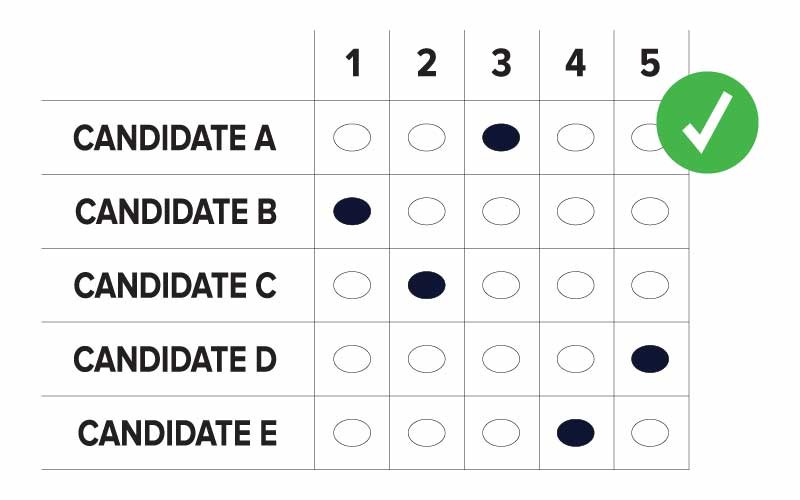

Ranked choice voting is a method that overcomes the issue of spoiler candidates. With ranked choice voting, instead of choosing only one option in a list of candidates for an office, voters choose multiple candidates they support in order of preference. Voters only rank the candidates they like and are never forced to rank—maybe they only align with one or two of the people running, so they rank those two and leave the rest blank. In most places using ranked choice voting, voters can rank five or six candidates if they wish; some places allow as many rankings as there are candidates on the ballot.

The most common way to tally ranked ballots is known as “instant runoff,” where all first-choice votes are tallied first. If just one person is being elected, they need a simple majority of votes to win: 50 percent of the total votes cast, plus one. If no one gets a majority in the first round, the candidate with the fewest votes is eliminated and the people who voted for the eliminated candidate get their second choice counted in a second round—the “instant runoff” at work. Meanwhile, voters whose top choice was not eliminated continue to have their votes counted for their first choice. Vote counting continues like this until one candidate wins a majority.

The method negates any fear of spoiler candidates because voters can have their vote for their second-choice candidate count when their first-choice candidate is eliminated. And it guarantees that the winner earns a majority of votes cast.

Types of Elections: General, Runoff, Primary, and Special

Plurality or ranked choice voting can apply to most types of elections.

General elections usually determine who actually wins office. For federal and most state offices, general elections are held on the Tuesday following the first Monday in November (“Election Day”), in even-numbered years for federal offices and varied cadences for state and local offices depending on state law.

Runoff elections happen in some states that require a majority winner. In the 2022 US Senate race in Georgia, for example, neither Raphael Warnock nor Herschel Walker won a majority of votes in the November election, leading them to compete in a runoff four weeks later (won by Warnock). As noted, ranked choice voting is a form of “instant” runoff, where voters don’t need to revisit their polling place on another day because they’ve already expressed their alternative choices on a ranked choice ballot.

Primaries (sometimes called “party nominations”) are often used prior to a general election to winnow the field of candidates.2Because some districts’ voters lean heavily toward one party or another, primary elections are sometimes more competitive than general elections and effectively determine who will win the office. In a definitively “red” district, the Republican primary winner is likely a shoo-in for the general.

In some cases, the primary election officially determines who wins: in local, nonpartisan elections in Oregon, for example, a candidate who wins a majority of votes in the primary is elected without needing to run in the general election. Those candidates often don’t actually have the support of a majority of their constituents, however, because fewer voters participate in primary elections. In the 2018 election for Portland’s city commissioners, Nick Fish and Jo Ann Hardesty both won their citywide seats with 62 percent of the vote. But Fish’s win came in the primary, where he won with 74,161 votes (out of an electorate of about 120,000 voters), thus bypassing the general election, while Hardesty won in the general election, with 165,686 votes—more than twice as many supporters. Loretta Smith, who lost to Hardesty in the general election, received more voter support (99,823 votes) than Nick Fish did during his primary election win.

All these elections are scheduled regularly throughout the election calendar, but vacancies or other changes sometimes require a special election to fill a seat. There can be special general elections, special primaries, and special runoffs, as needed. United States Representative Mary Peltola in Alaska, for example, was first elected in a special election after Rep. Don Young died while in office, with a special primary election in June 2022 and a special general election in August 2022. Some school district boards or other smaller governing bodies are also elected during special elections.

Primaries: Nonpartisan or Partisan, Closed or Open

Primary elections have enormous variability. Most are administered and paid for by official election administrators at the state or local level, although some are fully managed by political parties themselves. Primaries are either partisan (limited to a single party) or open to all candidates; partisan primaries can be open, closed, or in between.

The rules governing state, local, and presidential primaries can vary considerably even within a single state. Oregon, for example, uses closed partisan primaries for legislative offices (i.e. Republicans voters participate in a Republican Party primary) but nonpartisan, open primaries (and top-two) for local positions. Presidential primaries often use a distinct format (and are held at a separate time) than other state primary elections—such as how Alaska’s presidential primaries are still run by both parties separately, while the more regular primary for state and federal seats is nonpartisan and managed by the state.

Partisan primaries: Closed, open, or somewhere in between

In a closed, single-party primary, voters can only vote in the primary if they’re registered with a major party (these days usually either Democrat or Republican—although in most cases other official parties can choose to hold their own primaries as well). Closed party primaries give parties more control over their nominees and prevent members of the opposing party from influencing who becomes their general election candidate.

But closed, partisan primaries also lock out a lot of potential voters: in places with fully closed party primaries, independent or unaffiliated voters—the fastest-growing political identity in the US—do not get to vote at all. If you’re not a card-carrying, registered Republican in Wyoming, for example, you cannot vote in the party primary. Closed partisan primaries also favor extreme candidates who are popular with a party’s committed base of voters (who are more likely to cast a vote in a primary) but may not be preferred by the full spectrum of voters within a party, let alone the general electorate.

Oregon uses closed partisan primaries for state and federal offices, as does Idaho, so only party members participate. This means that the more than one million unaffiliated voters in Oregon, in addition to the voters registered with smaller parties that do not hold primaries, do not have a say in which candidates wind up on their general election ballot.3

Some partisan primaries are partially closed or partially open, where only registered Democrats can vote for the Democratic primary slate and Republicans for the Republican primary candidates, and unaffiliated voters can cast a vote in either one but not both.

In a fully open partisan primary (such as in Montana), all voters choose which party’s ballot they’d like to vote on. Voters don’t have to register their affiliation with a party, so they can cross party lines without consequence. Critics argue that this situation encourages some voters to choose an opponent from the other party who is unlikely to beat their preferred candidate in their own party, but proponents note that it offers voters more flexibility.

Each separate party within a given state does not have to choose the same degree of openness. Before Alaska instituted nonpartisan open primaries and ranked choice voting, for example, the Alaskan Republican party held fully closed primary elections, but the Democratic primary was only partially closed and allowed unaffiliated voters to participate.

In addition to states that hold a runoff for the general election, some states hold runoff elections for their partisan primaries if one candidate doesn’t clear a threshold (usually a majority) to determine which party candidates advance to the general.

One unified any-party primary

More and more states are looking to offer a single, unified open primary, with just one primary ballot that lists all the candidates, of any party, rather than separate ballots for each party.

This type of primary is often labeled “nonpartisan” to distinguish it from partisan primaries, but party labels can sometimes be attached to candidates, with or without the official endorsement of the party, so it can also be called a “multi-party” or “all-candidate” primary. And the single, unified primary is “open” since all voters can participate, not just those who are affiliated with specific parties. (Watch out for the terms here! “Open primary” can refer to a nonpartisan open primary or a partisan open primary.) Some research has shown that holding a single open, nonpartisan primary rather than dual partisan primaries reduces polarization, since the most extreme candidates tend not to move forward, but the effects depend in part on how the general election is run.

Washington, California, and Alaska all use a unified open primary (as well as Nebraska, although only for state legislative offices). In all but Alaska, the top two vote-getters of any party move forward; in Alaska, the top four candidates advance to the general election, where the winner is then determined using ranked choice voting.4

In most states, most local elected offices are nonpartisan and use a top-two format when they have a primary (although primaries are rare for these offices).

Voting in a primary, general election, or both

How do all these distinctions pertain to ranked choice voting? Jurisdictions can use ranked choice voting in their primaries, general, or special elections, or all the above. And they can adopt it with or without adjusting other aspects of the elections. Alaska changed its primary election format when it switched to a statewide ranked choice voting general election. Maine did not; nor does Oregon’s proposal.

Thanks to Jeannette Henderson & Andrew Behm for supporting a sustainable Cascadia.

Our work is made possible by the generosity of people like you.

The benefits of ranked choice voting are apparent in each context, although they show up a little differently depending on where it fits into the existing elections framework. Here are five scenarios describing ranked choice voting’s use in the region (and in the table below).

1. Unified nonpartisan primary + a ranked choice voting general

The combination of voting methods used for state and federal elections in Alaska offers clear benefits that my colleague Jeannette Lee has written about extensively: an open, nonpartisan primary that establishes the top four candidates who advance to the general election, and a general election using ranked choice voting.

Voters in Nevada will decide this November whether to adopt an Alaska-style system, though the proposed model in Nevada would send the primary’s top five (rather than four) candidates to the general election. Colorado and Idaho voters will likely also weigh this “final-four” or “final-five” voting option for their primaries.

Under this framework, all voters get to participate in the single, unified primary election and can vote for their favorite candidate, of any party, sending four (or five) top candidates forward. In the general election, ranked choice voting removes the fear of voting for a spoiler candidate, because even if a voter’s first-choice candidate does not advance, their second choice can count instead.

Under its combination of unified open primaries and ranked choice general elections, Alaska has seen more Independents and women run for office, more competitive elections, more Independents win, and polarizing candidates punished. While the election method can’t claim all the credit for these improvements, it is an important factor that voters appreciate.

2. No primary + a ranked choice voting general election

Most local elections that incorporate ranked choice voting offer it in the general election and eliminate the primary (if they had one). Benton County and the city of Corvallis, both in Oregon, have used ranked choice voting for some offices when there are more than two candidates in their general elections. Usually there aren’t enough candidates to necessitate a winnowing primary, so this application of ranked choice voting sees the same benefits of the Alaska model at a local level. The elections office can also save money by not having to add those offices to a primary ballot, sometimes even eliminating the primary election altogether.

In Portland, Oregon, starting this November, voters will use single-winner ranked choice voting for mayor and city auditor and multi-winner ranked choice voting for city council positions, with three winners in each of four new districts. Similarly, there will not be a primary, and since Portland is larger than Corvallis and the electoral changes are part of a holistic overhaul of the city government that negates most incumbency advantages, there are already quite a few candidates running for each seat—voters will have a lot of choice on their ballots.

Nixing the primary and opting for a single ranked choice general election is a model also used in Minneapolis, Minnesota; San Francisco, California; Boulder, Colorado; Portland, Maine; Salt Lake City, Utah; and quite a few more. These places have experienced a large increase in the people of color and women elected to office that better matches their diverse populations, and less vitriolic campaigns after adopting ranked choice voting.

3. Partisan primaries + a ranked choice voting general election

Oregon voters will have a chance this November to adopt ranked choice voting for statewide and federal offices (including Governor, Secretary of State, US House, US Senate, and a few others). Since the measure won’t affect Oregon’s closed, partisan primary system, the proposed changes are akin to what Maine voters have used since 2018, combining mostly closed partisan primaries with a ranked choice voting general election (although Maine changed this year to semi-open primaries rather than closed, now offering an option for the 30 percent of unaffiliated, independent voters in Maine to have a voice in the primary).

With a partisan primary and a ranked choice voting general election, each major party chooses one nominee to send to the general election. In Maine and in Oregon’s proposal, the parties use ranked choice voting to determine their nominees, ensuring that each candidate is supported by the majority of each party’s primary voters. Then in the ranked choice voting general election, candidates from non-major parties can also run—and don’t have to worry about spoiling the election for the major-party candidate most similar to them. A Green party candidate, for example, can run without taking votes away from an issue-aligned Democrat, because voters who choose the Green party candidate first can have their second choice count if the Green candidate doesn’t get enough first-choice votes.

While the closed partisan primary does not allow all voters in the state to participate in the early stage of the process, using ranked choice voting in the general election helps to combat party extremes because it opens the door for alternative choices on the ballot and encourages partisan candidates to reach out to voters beyond their base to gain second-choice rankings.

4. Ranked choice voting primary + a top-two general election

Washington’s state law currently requires top-two general elections—but ranked choice voting can still come into play within that framework and will in Seattle, starting in 2027.

Voters in Seattle decided in 2022 to adopt ranked choice voting for city primaries in part because of pitfalls with the top-two system, which reduces the spoiler challenge inherent to a basic plurality system but doesn’t entirely alleviate it. Under the current top-two rules, voters choose one candidate in the nonpartisan primary, and the two candidates with the most votes advance to the general election. By only allowing two candidates to compete in the general election, voters with similar issue preferences will not split their votes between multiple candidates.

But spoilers still happen with top-two—they just happen in the primary instead. In 2016, the primary election for Washington state treasurer had five candidates: three Democrats and two Republicans. Voters were split between the three Democrats, and the two Republican candidates ended up winning the most votes and advancing to the general election—leaving the state’s majority of Democratic voters without a candidate.

Top-two elections can also create perverse incentives for candidates running in the primary, as was seen recently in California’s top-two primary for Senate. Democrat Adam Schiff boosted Republican Steve Garvey—seeking, and succeeding, to contend with an easily beatable Republican candidate in the general election rather than fellow Democrat Katie Porter, who would have been a more competitive opponent in California.

Operating under Washington state’s requirement for only two candidates in the general election, Seattle voters opted for ranked choice voting where it’s allowed: in the primary. Seattle is the only jurisdiction Sightline is aware of that will use ranked choice voting in a single, nonpartisan primary election but not the general (Arlington, Virginia, and New York City adopted ranked choice voting for primaries and not the general election, but they both have partisan primaries).5In some ways, it’s an odd combination: the winner of the ranked choice primary election will have shown they have majority support, although since fewer people vote in the primaries, the outcome might very well change in the general. If Washington state law allowed it, using ranked choice voting in the general election makes more sense, and the city could even potentially eliminate the primary altogether.

But Seattle voters will still benefit from this combination: in a crowded primary field (which mayoral races tend to be—there were 15 candidates in 2021), they’ll be able to express their true preferences without worrying about which candidates are the most popular.

5. Plurality, sometimes with a small side of ranked choice voting

Idaho, Montana, and British Columbia all use plurality voting methods. This means that some of their elected leaders are voted in by less than half of the voters, and spoilers abound.

In Idaho’s Republican primary for Secretary of State in 2022, for example (which is usually more competitive than the general election for statewide offices, since Idaho voters lean heavily Republican), Phil McGrane won with only 43 percent of the Republican vote, just a few thousand votes more than second-place Dorothy Moon. But a third candidate, Mary Souza, received 15.5 percent of the vote—far more than enough to change the election.

A group in Idaho has gathered signatures for a ballot measure to implement top-four open primaries and ranked choice voting general elections statewide, which would prevent spoiler candidates and non-majority winners in future elections. A similar campaign has also gathered signatures in Montana.

Elsewhere in the US, some states with plurality systems use ranked choice voting for military and overseas voters, including Alabama, Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, and South Carolina. Ranked choice voting allows them to avoid sending out new rounds of ballots to these far-flung voters under a challenging timeline in the event of a runoff.

More consistently representative elections are possible—and adaptable to local needs

Ranked choice voting performs better than plurality and top-two by a number of metrics: voters get more options, winners are more likely to be bridge-builders because they’ve proven broad appeal, campaigns are positive and inclusive, and the change creates momentum for further reforms that help voters.

Here, Sightline has illustrated how ranked choice voting can apply flexibly in a variety of electoral contexts in Cascadia, from Oregon to Seattle to Alaska and beyond. People interested in a healthier, more substantive, and more effective democracy have successfully adapted these options to suit their locales and better represent voters—and others can, too.

| The Alaska Model | Upcoming in Seattle | Local in Oregon | Potentially Statewide in Oregon | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Which type of primary? | Nonpartisan | Nonpartisan | None | Partisan |

| Which voting method in the primary? | Plurality | Ranked choice voting | N/A | Ranked choice voting |

| How many candidates move forward? | 4 | 2 | 3 or more | 1 per party (2 or more total) |

| Which voting method in the general election? | Ranked choice voting | Top-two | Ranked choice voting | Ranked choice voting |

| Which places use this election combination? | State and federal offices in Alaska | Upcoming in Seattle starting in 2027 | Currently in Benton County, Corvallis, and upcoming in Portland, Oregon, starting in 2024 | Federal and some statewide offices in Maine, and on the ballot in Oregon |

| What are the implications? | This format offers real choice to all voters: The open primary allows all voters to participate and ranked choice voting in the general election ensures that voters can express their true preferences. | Voters can express their true preferences in the primary election. | With ranked choice voting in the general election, voters can express their true preferences between the mix of candidates. Eliminating the primary election can save money. | Keeping the previous election format for the primary keeps the parties engaged. And ranked choice voting in the general election prevents third-party candidates from spoiling the election for a similar major-party candidate. |