Takeaways

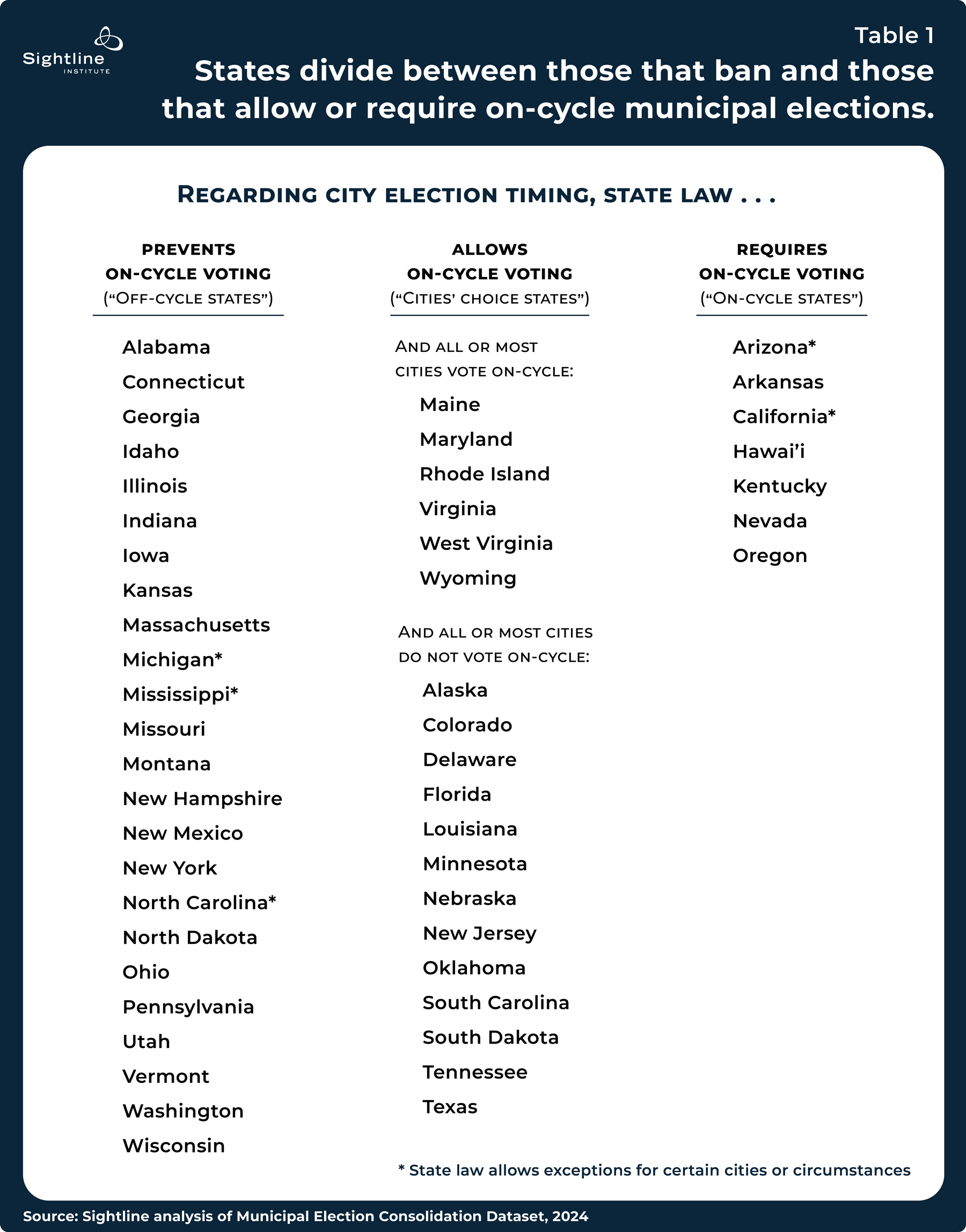

In 24 US states, state law bans cities from adopting the single most effective technique for boosting voter participation—scheduling local elections on the same date and ballot as national elections—according to a new dataset of all 50 states and 420 large cities assembled for this report. In 19 other US states, state law allows cities to adopt that technique.

In seven US states, such “consolidated” or “on-cycle” city elections are required by law. Overall, among 420 large US cities, some 57 percent hold off-cycle elections, while 43 percent vote on-cycle.

State legislators in 43 states can advance local election consolidation. Eighteen “trifecta” states may be particularly ripe for consolidation, and an overlapping set of 13 states can adopt the reform through citizens’ initiative processes.

City councilors in 101 large off-cycle cities already have authority to consolidate their elections. In 21 of them, they can do so by majority vote. In the others, they may need to refer the question for voter approval. Such approval is almost always given (21 of 22 times in the past decade). In 32 of the 101 cities, local citizens’ initiatives can likely initiate the change.

Some 59 large cities are partly on-cycle but can fully consolidate elections under their own authority by discontinuing “short-circuit” primaries, runoffs after November, and annual elections.

The new 50-state, 420-city dataset summarized in this report provides a fine-grain map of how Americans can seize the colossal opportunity to strengthen democracy offered by election consolidation. In the past two decades, three states and more than 50 large US cities have consolidated their elections. Reform efforts are afoot in many more.

Find audio versions of Sightline articles on any of your favorite podcast platforms, including Spotify, Google, and Apple.

The best-kept secret of boosting voter participation is election consolidation. Moving local elections to the same ballot as national ones increases turnout more than any other election upgrade, often doubling participation in local races. Synchronizing elections is popular with voters, for whom it saves time and hassle. When asked whether to consolidate elections, voters almost always vote yes by large margins. Consolidation also improves representation of voters who are working-age, renters, and less wealthy; dilutes the political influence of special interests; is more effective than unsynchronized elections in selecting local officials whose actions align with the wishes and beliefs of local majorities; enhances the accountability and legitimacy of local government; does not favor one political party over the other, nor any particular political ideology; and can save millions of taxpayer dollars.

At present, though, a large majority of US cities and towns hold their elections out of sync with national elections, a practice elite reformers started more than a century ago to dampen the influence of ethnic voters and their political “machines.” These “off-cycle” elections are relegated to a wide range of dates that are locked in by state or local laws.

A trend toward election consolidation has emerged in recent decades and has picked up speed, with scores of cities rescheduling their elections to ride the turnout coattails of national voting and save money. Nationwide in the United States, more than 50 large cities (including almost all cities in Arizona, California, and Nevada) have consolidated their elections in the past two decades. In 2022 alone, a dozen localities passed ballot measures to move their voting to the first Tuesday after the first Monday in November.

Until now, no one has assembled a reliable directory of when municipal elections are held in major American cities and what laws dictate those schedules. Consequently, leaders, journalists, reformers, and scholars have been hard-pressed to understand the dimensions of off-cycle voting or track its trends.

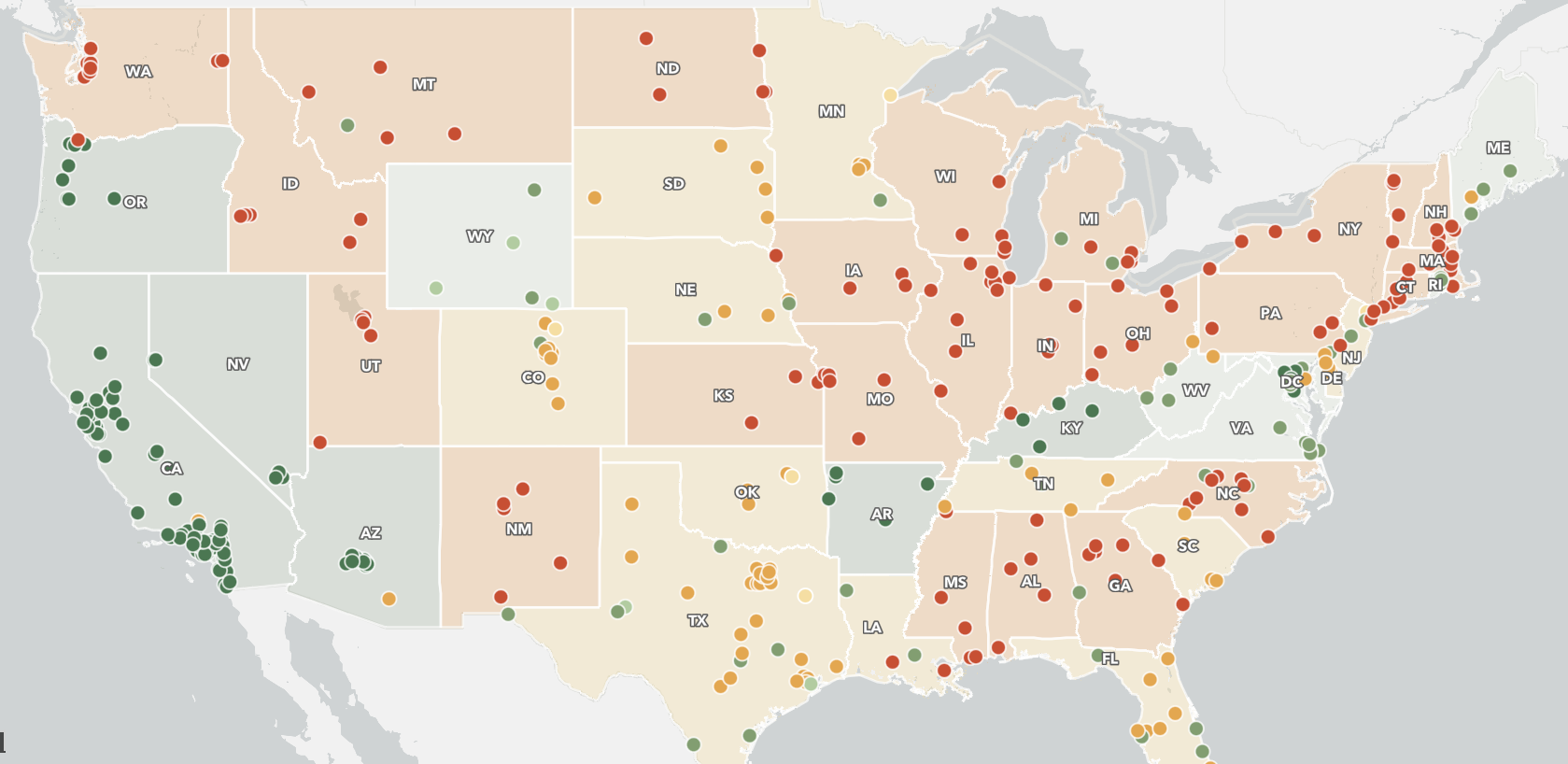

This report presents and summarizes Sightline’s Municipal Election Consolidation Dataset (click to download), a new dataset on election timing in all 50 US states and the District of Columbia, and an associated interactive map.

View the map in a new windowThe dataset details what state law says about municipal election schedules. It also includes election timing information for 420 large US cities—home to more than 102 million people. These cities include the five most populous cities in each state and all US cities of more than 100,000 residents.

By examining state constitutions and laws for all states plus municipal charters and ordinances for all these cities, Sightline identified not only when elections are currently scheduled but also the legal basis for those calendars. In other words, Sightline pinpointed what statutes leaders would have to revise to move elections from their disparate off-cycle dates to national election day.1 Where possible, Sightline also identified what steps would be required to consolidate elections in each city and whether action by state legislature, city council, citizen petition gatherers, popular vote, or some combination would be needed. The dataset, map, and report therefore serve as a detailed guide for how Americans can dramatically boost voter participation and strengthen their democracy.

Election Timing in the States

As shown in Figure 1, Table 1, and the Municipal Election Consolidation map, in almost half (24) of the states, rules requiring off-cycle municipal elections are baked into state law; these states (let’s call them “off-cycle states”) include population powerhouses such as New York and Illinois plus all the Great Lakes states, most of the deep South, and the northern tier stretching west from the Dakotas.

In contrast, in seven states, state law now requires that municipal elections coincide with national elections in almost all cases. (We’ll call them “on-cycle states.”) These states are concentrated in the West and include Arizona, California, Hawai’i, Nevada, and Oregon.

In the remaining 19 states, state law allows municipalities to decide for themselves whether to hold on-cycle elections. (Let’s call them “cities’ choice states.”) They form a rough north-south line bisecting the nation and are scattered elsewhere.

The 24 off-cycle states contain 138 of the 420 large US cities in the dataset, including New York and Chicago. These 138 cities are home to 36 million people. At the other end of the spectrum, in the seven on-cycle states are 117 large US cities, including Los Angeles and Phoenix. These cities are home to 29 million people.2

In the 19 cities’ choice states, on-cycle elections are still outliers. As shown in Table 1 and Figure 1, in 13 of these states, including Florida and Texas, all or a majority of large cities hold off-cycle elections. In the remaining six, on-cycle elections are the norm. Three of these states cluster together with on-cycle Washington, DC: Maryland, Virginia, and West Virginia. Among the 165 large cities in the 19 cities’ choice states, only 64 cities have opted for on-cycle elections.

For Arizona, California, and Nevada, allowing cities to choose on-cycle elections was a first reform step approved by the legislature. After these states each empowered cities with the choice, a trickle and then a stream of cities started consolidating their elections. Later, a decade or more after these states allowed cities the option to consolidate, they required most remaining cities to do so.

Election Timing in Large US Cities

Shifting the unit of analysis from states to cities, a finer-grained picture emerges, as shown on this page of the Municipal Election Consolidation map. Overall, among all 420 large US cities in the dataset, some 239 cities (57 percent) hold off-cycle elections (see Figure 2). Some 138 of these 239 do so because of state law; the others follow local law.

View the map in a new windowMeanwhile, among the 181 cities (43 percent of all cities in the dataset) that hold on-cycle elections, state law and local law also contribute in similar measure to election timing. Some 117 cities vote on-cycle because state law requires it; the remainder made the choice for themselves through a municipal charter or ordinance.

Aided by population giants New York, Chicago, and Houston (the first, third, and fourth largest US cities, respectively), the 57 percent of cities that vote off-cycle account for a disproportionate 60 percent of the overall population of the country’s largest cities. The remaining cities, which vote on-cycle, include Los Angeles and Phoenix (the second and fifth most populous, respectively). Indeed, among the nine US cities with populations of more than 1 million (shown in Table 2), three vote off-cycle by state law, three vote off-cycle by local law, and three vote on-cycle by state law.

The pattern this report documents for large cities is indicative of the pattern for small cities and towns as well. In states that dictate municipal election timing, the same schedules usually apply to all municipalities. In states that let cities choose, smaller cities typically follow any default election dates set in state law or simply emulate the election schedule that major cities observe.

A Growing Trend

For the first century of US history, local elections bounced around the calendar, pushed this way and that by different parties and factions pursuing electoral advantage. Then from 1894 to 1917, the Progressive movement seized on election timing as a tactic for smashing American cities’ “political machines,” in which local leaders coordinated networks of patronage to hold power and mobilize ethnic voters for their political parties. The Progressives’ motives may or may not have been pure, but their record was mixed: they fought corruption partly by disenfranchising working-class voters. By severing city elections from national ones and scheduling them at odd times of year, they walled city government off from mass participation and made it a redoubt of elites—of an older, whiter, wealthier, WASPier, native-born homeowning class. It has remained that way ever since.

Indeed, once off-cycle city elections had been enshrined in state law and city charters in the Progressive era, they became conventional wisdom. Hardly anyone even thought about why local elections were not on the same ballots as state and federal elections. An entire culture of local politics evolved around off-cycle elections, and this culture suited incumbents well enough: a smaller electorate can be comforting to a politician who understands it well and plays to its predilections.

By 1940 the Progressive cause had prevailed almost everywhere: US city elections were overwhelmingly off-cycle, according to scholar Dr. Sarah Anzia.3 Half the states Anzia studied had exclusively off-cycle city elections, and more than a quarter had off-cycle elections in all but a few token cities. Add the numerous states where a majority of cities voted off-cycle, and only three had mostly on-cycle city elections: Indiana, Oregon, and Rhode Island. (Indiana subsequently switched to off-cycle as well.)

As the 1900s continued, though, the tide began to run in reverse, first slowly and then faster. A trickle became a stream. Baltimore, Maryland; San Diego, California; Washington, DC; Sarasota, Florida; Trenton, New Jersey; El Paso, Texas—all began voting on-cycle. No single source of data captures the trend thoroughly or authoritatively, but four different databases point in the same direction. (To read details about the four databases, please expand the section below.)

A database of local US elections published in early 2024 by Justin de Benedictis–Kessner of Harvard University and Christopher Warshaw of George Washington University includes nearly 18,000 individual city council seat elections between 1989 and 2021. A preliminary analysis of this database by Zoltan Hajnal of the University of California San Diego found that the share of these races decided in November of even–numbered years before 1995 was 13 percent; after 2017, that figure had almost tripled to 37 percent. Because the database was assembled with other purposes in mind, its accuracy on trends in election timing may be imperfect.

As detailed previously, the share of Golden State cities with on-cycle elections may have been as low as 4 percent in 1940, but by 1995, after a steady stream of cities consolidating elections, it was 62 percent. Much better time-series data is available thereafter, according to a state-sponsored elections database. As shown in Figure 3, the on-cycle share rose to 96 percent in 2022 as 153 California cities moved to on–cycle. Though it only covers one state, this database is highly accurate.

A dataset assembled by Adam Dynes of Brigham Young University and collaborators covers 1,600 US cities of all sizes in the middle of the first decade of the 2000s. It estimates that 22 percent of these cities ran elections on–cycle. Sightline compared these same cities’ election schedule around 2005 with its own 2024 data for cities, the California 482-city database, and other sources. Sightline estimates that 140 additional US cities (9 percent of the total sample) consolidated their elections between 2005 and 2024. This Dynes dataset seems as or more accurate than the 18,000-election dataset but less accurate than the California and Sightline datasets.

Of the 420 cities in Sightline’s dataset, some 378 were also in the Dynes database. Of the cities for which we can make “then-and-now” comparisons between the mid-2000s and 2024, some 54 (14 percent of the total) moved from off-cycle to on-cycle elections. Most of the switchers were in Arizona, California, or Nevada, but Texas, Florida, and Virginia also had several each. Sightline’s data, because it is more of a handmade catalog than a mass-produced database, is highly reliable, though it covers fewer cities than the other databases.

All four databases show a trend toward on-cycle municipal elections. The trend has been especially strong in the US West, where Arizona, California, and Nevada (once overwhelmingly off-cycle states) are now almost entirely on-cycle, joining longtime on-cycle Western states Oregon and Wyoming.

What will it take to accelerate this trend?

States’ paths to consolidation

States are the final legal authorities on city election schedules, so state legislatures are important arenas for reform. In Idaho, New York, Washington, and Montana, state legislators have recently considered bills that would consolidate local elections. In 2023 New York legislators approved and the governor signed a bill to consolidate county and town elections in November of even-numbered years. (In most states, county elections are already consolidated with state elections.) In New York and Pennsylvania, a constitutional amendment is required to consolidate city elections because election timing is specified in the constitution. Reformers in New York are working to win such an amendment.4

In Washington, a 2024 bill that allows municipal election consolidation passed through two House committees, a House floor vote, and a Senate committee before dying without a vote in a second Senate committee. Two different reform measures, both for mandatory election consolidation, passed in Montana’s two legislative chambers in 2023. The two chambers failed to reconcile the versions before the legislative session ended, but proponents expect to try again the next time the legislature convenes in 2025. Idaho’s legislature also saw an election consolidation bill in 2023, though like most pieces of legislation, it did not win time on its committee’s agenda and therefore died unheard. Many other states considered election consolidation measures (57 bills in 2022 and 2023 by one tally) and 14 passed into law, though they focused on other offices than city council or moved elections to dates with higher turnout but not to November of even-numbered years. (For example, Idaho moved its presidential primary to the state’s regular primary election ballot, and West Virginia pruned its calendar of special election dates.)

Reversible partisan support

The politics of election consolidation in state legislatures follow an unusual pattern: the polarization reverses with the state’s partisanship; that is, in red states such as Arizona, Idaho, and Montana, election consolidation has been a Republican cause, opposed by Democrats, and in blue states such as California, New York, and Washington, it has been a Democratic cause, opposed by Republicans. Only in Nevada has election consolidation recently won strong bipartisan support in the state legislature.

Given this pattern of reversing polarization, “trifecta” states (states where the same party controls both legislative chambers and the governor’s office) stand out as likely candidates for reform. Six Democratic-trifecta states and twelve Republican-trifecta states (see Table 3) currently ban on-cycle city elections. As noted, reform campaigns to allow or require on-cycle city elections are underway in some of these states, including Republican Idaho and Montana and Democratic New York and Washington.

Ballot Measure States

In 16 states, election consolidation could come through a ballot measure that members of the public initiate. All these states have a citizens’ initiative ballot measure process through which voters can change state law, including law governing municipal election timing. In eight of the states, state law currently dictates off-cycle municipal elections (see Table 4), and reformers could attempt to put a ballot measure before the voters. Because voters almost always vote yes on election consolidation, any petition that qualifies for the ballot is likely to win approval.

In eight other ballot-measure states, state law allows on-cycle municipal elections. Five of these states (shown in Table 4) might be ripe candidates for petition drives to require on-cycle local elections or, in the case of Colorado because of state constitutional provisions, to strongly encourage on-cycle elections. The other three states are less promising or more complicated. In Wyoming, most cities already conduct on-cycle elections of their own volition, so statewide reform would do little. In the other two states (Alaska and Maine), term lengths would complicate election consolidation. In Alaska, city assembly members and mayors serve three-year terms, and in Maine some serve one-year terms. Synchronizing city elections to November in even-numbered years in these states would require changing not just election schedules but also term lengths, which makes reform a heavier lift.

City paths to consolidation

Paths to reform are open at the city level in the 19 states where cities choose their own election calendar, either through council action or public vote. As noted above, some 101 large cities in these states currently vote off-cycle. Because voters almost always approve election consolidation when asked on the ballot (21 of 22 times since 2015), a key question is which of these paths is available in which cities.

In almost all the 101 large cities in question, city councils can initiate the move to on-cycle elections, though in many of them, the council does not have the last word. A key distinction is whether election timing is written in regular city ordinances or whether it is written in a city’s home-rule charter, if the city has one. States vary in the structure of their laws about charters, and consequently these documents’ prevalence and contents vary state by state. City charters themselves also vary greatly in what they specify about election schedules and about the process for amendments. Often where election timing is in the charter, not just in the ordinance, the city council must refer changes to the voters for majority approval. Sightline’s dataset specifies for almost all cities whether election timing is in the state constitution, state law, city charter, or city ordinance; it therefore serves as a guide to reform paths for almost all cities.

In some states, state law specifies how cities may change their election schedule. Colorado says, for example, that local public votes are required to reschedule elections, while Florida, Minnesota, New Jersey, Texas, and Virginia give city councils authority to consolidate elections without a public vote. (See Table 5 for 20 of the most populous US cities in cities’ choice states—places where city councils can initiate change.)

Overall, among the 101 large off-cycle cities in cities’ choice states, some 80 percent have lodged their election schedule in their charter. These cities include Denver, Miami, and Minneapolis, for example. Changing charters is harder than changing ordinary laws, but charter amendments happen all the time. In the remaining cities, including Arlington, Texas; Gainesville, Florida; all cities in South Dakota; and St. Paul, Minnesota, the election calendar is in city ordinances, which city councils can always rewrite themselves.

Meanwhile, in 32 of the 101 cities, local citizens’ initiative ballot measures are legal. Three of these cities (Wasilla, Alaska; Greeley, Colorado; and Saint Paul, Minnesota) have the good fortune of coincidence: the election schedule is in their ordinances (rather than their charters) and there are municipal citizens’ initiative processes. Residents of these cities can consolidate elections by initiative, even without city council support.

View the map in a new windowIn the remainder of these 32 cities, citizens bypassing the council to commence consolidation depends on whether the city’s charter allows reform by citizens’ initiative. Rules vary; some allow and some ban amendment by initiative. In Seattle, Washington, for example, either the city council or a signature drive can put a charter amendment before voters. Sightline’s municipal election consolidation dataset reports where election timing is lodged in law and whether cities have initiative processes but not whether charter reform is permitted by initiative.

Special cases: Short-circuit primaries, winter runoffs, and annual elections

Of the 181 cities that ostensibly vote on-cycle (shown on this map), some 59 cities in 14 states employ peculiar election rules that squander some of the turnout benefits of on-cycle voting. For example, some 33 cities, including Los Angeles and Las Vegas, use short-circuit primary elections (that is, if a candidate wins a majority of votes cast in a primary election held before the November general election, the general election for that position is canceled and the primary winner is automatically elected). The result is that in some races, the decision is made in a low-turnout primary, disenfranchising the more-numerous November voters.

In 19 cities, if no one in a November general election wins a majority, a subsequent runoff election ensues. Winners in cities such as Austin and Phoenix are then chosen in low-turnout runoffs, typically in December or January, by far fewer citizens than in November.5

Finally, in another nine cities, elections are in November, but they happen every year. Their city offices typically have staggered terms. For example, in Arlington, Virginia, and Midland, Texas, some city council members are elected on-cycle, by large electorates, and others are elected off-cycle, by small electorates. In Wichita Falls, Texas, two cohorts of councilors serve staggered three-year terms, and November elections only happen two in every three years. Some Maine cities have one-year terms and annual elections, while others have staggered two-year terms.6

In these cities, improving on-cycle elections would require methods that ensure November of even-numbered years is decision time for all city races, such as discontinuing short-circuit primaries, for example, and electing plurality winners in November or switching to top-two primaries or ranked choice voting in general elections. Cities with annual elections would have to shift from council cohorts elected each year to cohorts elected every other year (for two- or four-year terms), which is the pattern in most US cities.

A landscape of opportunity

Sightline’s new data on election timing and its legal basis in all 50 states plus the District of Columbia and in 420 large US cities provide a detailed picture of the colossal opportunity election consolidation offers as an upgrade to democracy. The data also provides a map to winning that upgrade. In 24 states, the first step may be to allow cities to move their elections on-cycle. The 18 trifecta states that ban on-cycle elections (12 Republican and 6 Democratic) may be good places to start in the search for legislative action, though bipartisan adoption as in Nevada may be possible in any of the 24 states. In eight of these off-cycle states, statewide citizens’ initiative processes provide an alternative to legislative action.

In the 19 states where cities are already allowed to hold on-cycle elections, it may be time to encourage or require on-cycle elections, as Arizona, California, and Nevada did after first allowing on-cycle elections for several years. State legislatures could take this step in any of these states; several of the states are prime candidates for election consolidation through statewide citizens’ initiatives.

In the 101 large cities that currently conduct off-cycle elections within these 19 states, city councils can act without state government approval. Of these cities, 20 percent can pass ordinances to reschedule the vote, and in the others, the councils can initiate charter amendments to make the change, following their own state or local process, which often includes a public vote. Meanwhile, in 32 of the 101 cities, even if councils fail to act, citizens can spark change through city-level ballot measures of their own.

Unfortunately, even among the 181 large US cities that hold on-cycle elections, there is room for improvement: almost one-third of them diminish the turnout benefits of election consolidation by using short-circuit primaries, runoffs after the general election, or annual elections. No action from state governments would be required to end these practices; cities already hold authority to discontinue them.

Across the United States, the rewards of election consolidation beckon: fewer, better-attended elections; better representation of the electorate in all its dimensions; elected officials who better reflect their constituents’ beliefs and priorities; stronger mandates for those officials to lead, thanks to turnout that’s often doubled; less burnout and more turnout for voters—who benefit from less hassle and less time wasted, more participation in democracy; and millions of tax dollars saved.

The opportunities for upgrading democracy are many. Which states or cities will consolidate elections next?

Appendix: Guide to Sightline’s municipal election consolidation dataset and notes on methods and terminology

Sightline assembled the Municipal Election Consolidation Dataset, an Excel spreadsheet on election timing in all 50 states and the District of Columbia and in large US cities. This appendix explains the spreadsheet, including our methods and definitions of terms. The spreadsheet is available to view or download. It is abridged and does not include Sightline’s extra pages and sections of tabulation, filtering, and sorting.

We obtained most information by online browser searches. Usually we started with “[state name] municipal election code.” If that failed, we tried “[town]” or “[city].” When possible, we cited websites operated by the state. More commonly, the states’ web pages refer to proprietary websites (usually hosted by CivicPlus or American Legal Publishing). We then turned to searching for the five most populous cities in each state and all US cities with populations of at least 100,000. Where possible, we used information from the city charter or city ordinances for election dates. (In one state [Louisiana], we could not find election timing information for one of the five most populous cities [Lake Charles]; therefore, only four Louisiana cities are included.)

Several states have a general rule for election dates but cities are allowed to override it. In such cases, we looked for “[city name] municipal code” or “[city name] ordinances.” In cases where we did not find evidence that the city had selected a different date, we looked for evidence that the city had conformed to the state’s default date. We did that by looking for election results for the city in the year indicated by state law. We used results reported by the city, the county where the city is located, or local media, in that order. When we used election results as evidence for election dates, we included a link to the election results.

In many cases, where online information was insufficient, we contacted state and local election officials by phone or email to complete the spreadsheet.

Municipalities vary in what elected offices they have, such as mayor, city attorney, and city auditor. They also vary in the names they use for the same city offices, such as city councilor, city assembly member, aldermen/women, city commissioner, selectmen/women, and city supervisor. In almost all these cities, all city offices are elected on the same date of the year, though offices sometimes have different term lengths and are often staggered. Occasionally they are on different election cycles. For consistency in this project, we gathered data on city council elections. When possible, we noted if other city offices are elected on a different schedule.

We use the term “municipality” to cover both towns and cities. Some states make a distinction between the two, based on population, form of government, or other criteria. If the state mandates different election dates for cities and towns, we reported the dates for cities, as they are more populous.

“On-cycle” means that the main municipal (or general) elections for city council seats are concurrent with (and on the same ballot as) federal general elections on the first Tuesday after the first Monday in November (in other words, the first Tuesday after November 1) of even-numbered years. “Off-cycle” means that municipal elections are at any other time; they may be in odd-numbered years, including on the first Tuesday after November 1, or any other date in odd- or even-numbered years. In 45 of 50 states, state general elections are on-cycle, so on-cycle municipal elections are also concurrent with state general elections in all these cases.

“Main” and “preliminary” elections. Cities and states use many different terms and combinations of terms for their elections, including “primary,” “general,” and “runoff.” They also use those terms inconsistently; some cities call any first-round election that shrinks the pool of candidates a “general” or “general primary” election and any November final-round election a “runoff.” To avoid confusion, in this spreadsheet, Sightline devised three categories of city elections (preliminary, main, and runoff) and assigned each election studied to one of them, regardless of what terms their respective cities use.

Preliminary elections. These are elections that narrow the field. They are typically held in the spring or summer, and they always precede the main election. The most common name for preliminary elections is “primary” elections. Indeed, in the text of this report, we often use that term as synonymous with “preliminary.” In a minority of cases, these elections are separate party primaries, in which registered voters in each party cast ballots to narrow the field to one candidate per party. In the majority of cases, they are nonpartisan “open” or “blanket” primaries in which all candidates compete in the same race and voting usually narrows this field to two finalists. In some of these elections, if the top vote-getter receives more than half the votes cast, they are declared the winner and do not need to go on to the main election. We call these “short-circuit preliminaries” or “short-circuit primaries.”

Main elections. These elections are the ones for which legislators expect the highest turnout. They are often called “general” elections, and they are usually the final round of elections, following a preliminary election. In the text of this report, we often use the term “general” to mean “main.” They are often but not always on the first Tuesday after November 1, in even- or odd-numbered years. Sometimes they include one candidate each from various parties plus independent candidates and are won by the one who gets the most votes. Sometimes they are nonpartisan elections in which the top two candidates compete regardless of party and the top vote-getter wins. Sometimes they are followed by runoff elections.

Runoff elections. By our definition, these are elections that follow main elections and are almost always in winter, typically in December or January. They always involve only two candidates. They are called in places where majorities (rather than pluralities) are required to win an election and when no candidate in the main election wins a majority. In some jurisdictions they are called only to resolve ties; other jurisdictions resolve ties with coin tosses or card draws. This use of runoffs for ties is peripheral to Sightline’s project.

Charter vs general law cities. Some cities (typically larger ones) have home-rule charters that establish how city governments operate, akin to national or state constitutions. Others do not and instead operate under state general law; such cities are sometimes called “general law cities” or “code cities.” Some states further divide cities into legal tiers or classes based on population size or other criteria such as the specific type of charter they employ. These tiers occasionally influence their election schedule options. In most states, charter cities have more leeway in determining when and how they hold elections, although there may still be statewide regulation of issues like the dates on which elections may be held. In California, general law cities are not allowed to hold primaries. (A discussion of the differences between general law cities and charter cities in California can be found here.)

Thanks to John Russell & Mary Fellows for supporting a sustainable Cascadia.

Our work is made possible by the generosity of people like you.

The spreadsheet is organized in four pages or “tabs”: states, cities, notes, and data validation. The first two tabs contain all the data.

States

The States tab summarizes what Sightline learned about municipal election timing in all 50 states. We categorize the states into three groups in Column B, Does state law dictate or allow on-cycle municipal elections? The categories are whether the state requires, allows, or prevents on-cycle municipal elections.

Column C, Notes, describes municipal election timing in each state.

Columns D–F, Number and shares of cities, report the number of cities we studied in each state, how many of them vote on-cycle, and what share of studied cities that is. This data comes from the Cities tab of the spreadsheet.

Columns G and H, Year, frequency, and date of municipal general elections, detail local term lengths and election schedules.

Column I, Regulatory reference, provides and links to the relevant passages from state law.

Column J, Other elections, adds other linked passages from state law that are relevant to election timing.

Column K, Which party controls? notes whether the state was under a trifecta (control of the governor’s seat and both chambers of the legislature by the same political party) as of March 2024 and, if so, which party. Although municipal elections are officially nonpartisan in about 85 percent of US cases, partisanship is often just beneath the surface. The information in this column is from Ballotpedia’s catalog of trifectas as of April 2024.

Column L, Majority on-cycle? indicates whether, in states where cities are allowed to choose on-cycle elections, a majority of studied cities have done so.

Cities

The Cities tab (the spreadsheet’s main page) reports what Sightline learned about election timing in 420 large US cities—the five largest in each of the 50 states plus all cities with more than 100,000 residents as of 2022. (In Louisiana we could find information for only the most populous four cities.)

Column C, Population estimate, takes numbers from the 2022 estimates in the US Census Bureau’s “City and Town Population Totals: 2020-2022” (census.gov).

Column D, What, if anything, do city laws say about election timing? assigns each city to a single category from a list of eight. For the information in this column, Sightline ignored state law entirely and simply referred to city law. The column summarizes what the city’s charter or ordinances say about election timing. Sometimes this determines the city council election date, but sometimes it only reinforces or is overruled by the state law that actually determines the election date. If there is no information about the election date in municipal laws, then the state laws determine the date. If the city has merged with a county, then the date may be determined by state laws regarding county elections.

Column E, On- or off-cycle, and why? brings state law considerations to the information in Column D and specifies whether elections are on-cycle or off-cycle in each city. State law overrides municipal law in almost every case, so we refer to state law where it controls city election timing and categorize the city as “on-cycle by state law” or “off-cycle by state law.” If state law leaves the decision to cities, however, or if a city has won an exception from state law (as described below), we categorize the city as on- or off-cycle “by municipal code or charter.” The remaining categories, which hold few cities, include cases where we could find neither state nor municipal laws setting the date and relied instead on election results for purposes of categorization. These are usually posted by the county or municipality, but sometimes we had to use online results from local news media. Similarly, if the municipality holds annual elections and these elections are on the first Tuesday after November 1, then in some years these will be on-cycle and the following year they will be off-cycle. Such unusual cases are categorized as “annual” in Column D and “on-cycle by municipal code or charter” in Column E. Please note that some other cities also have annual elections on dates other than the first Tuesday after November 1; these elections are all off-cycle.

In a few cases, state law generally requires or prohibits on-cycle elections but allows certain exceptions. For those we list city law as the governing reason for that city’s election timing, even in states we otherwise list as requiring or prohibiting on-cycle elections. Examples include Tucson, Arizona, which won a court case to allow it to remain off-cycle despite state law requiring on-cycle elections, and Winston-Salem, North Carolina, which state law specifically authorizes to continue its longstanding practice of holding on-cycle elections.

Column F, Legislative reference, has hyperlinked quotations from the city’s charter (if it has one), from municipal ordinances that specify the date of the municipal general election for city council positions or from state law. Sometimes the municipal code says that it follows the state-mandated date. Cities without a charter are known as “general law” cities or “code cities.” These cities typically do not specify their own election dates but instead hold their elections at times specified in state law. We tried to link the information presented here to the most relevant of the cited documents.

Column G, Date of main city council election, notes dates that usually come from state or municipal election code. Some states, including Texas, merely specify that the election must be on one of a small set of possible dates, and some cities in Texas simply say that they follow the state-mandated election date. When this happens, we looked at posted election results to determine when elections happen.

Column H, Is there a preliminary? There are more cities that do not hold preliminary (or primary, see above) elections than there are cities that hold them. One reason cities hold preliminary elections is if the city council position is partisan, and most are not. Some cities hold “top two” preliminary elections in which only the two candidates receiving the most votes proceed to the main or general election. This column only addresses preliminary elections for city council positions. It does not consider preliminary elections for other positions, even for mayor, and it ignores preliminary elections for other levels of government, such as county or state.

Column I, Preliminary date, reports the date on which municipal city council preliminary elections, if any, are held. We again provided links to relevant sections of law whenever possible. “N/A” (“not applicable”) means that the city does not hold preliminary elections.

Column J, Is there a runoff? specifies when runoffs occur, if they ever do, and why. In some cities an election must be won by a majority of the voters; that is, by more than 50 percent of those voting; some require that there must be some margin of victory, such as 3 percent; and for some, winning just involves getting the most votes. Runoffs are held when no candidate has met the criteria for winning. Cities that hold preliminary elections usually don’t need to hold runoff elections. Cities that simply require a plurality for winning (i.e., the most votes) face the logical possibility of a tie vote. Some address this possibility in municipal code with runoff elections, coin tosses, or the drawing of lots. Some do not explicitly address the possibility. We divide cities among three categories: “No runoff,” “Runoff if there is no majority,” and “Runoff if there is a tie.” (Note: In our report, we do not address the third category.)

Column K, Runoff date, provides links to the relevant passage of law that specifies the timing of any runoffs that occur. “N/A” (not applicable) means that we did not find anything in the code to suggest that runoffs were possible.

Column L, Can a main election be skipped? provides citations, when possible, when the answer is yes, that explain the conditions under which the main election can be skipped. For example, in many California cities, if a candidate wins a majority of votes in a preliminary election, the main election is canceled for that race. We call these cases “short-circuit preliminaries” or “short-circuit primaries.” “No” indicates that we did not find anything suggesting that elections could be skipped.

Column M, Notes, documents exceptional cases, especially those cities that have partly (but not fully) on-cycle elections and why.

Column N, Notes 2, documents other salient information.

Column O, City initiative process, records whether each city provides for citizens’ initiatives by signature gathering and council action or public vote. Sometimes a city’s charter or code explains the process by which citizens can initiate changes to the charter or code. This is one way that elections could be moved to on-cycle. The other way would be through action initiated by the city council. Changing the election date might also involve changes at the state level. Not all states and not all cities allow citizens’ initiatives.

Column Q. Counts as on-cycle, assigns a “1” to cities that Sightline tallies as on-cycle and a “0” to all other cities, for tabulation purposes.

Notes: The Notes tab contains definitions and explanations and is partly duplicative of this appendix.

Data validation options: This tab makes the other tabs run. Readers may ignore it.

To view Municipal Election Consolidation map, click here

To download the Municipal Election Consolidation Dataset, click here

Acknowledgements

Thanks for research assistance to Ruth Greenwood and the 2023 summer interns of the Harvard Election Law Clinic: Macy Cecil, Grayson Hoffman, Leah Korn, and Sara Shapiro; dozens of election administrators who answered our questions; Erica McCormick at Cascade GIS for the maps; our Sightline colleagues for assistance with many aspects of this report; and Avi Green, Zoltan Hajnal, Neal Ubriani, and Ben Weinberg for comments on drafts of this report and dataset.