Find audio versions of Sightline articles on any of your favorite podcast platforms, including Spotify, Google, and Apple.

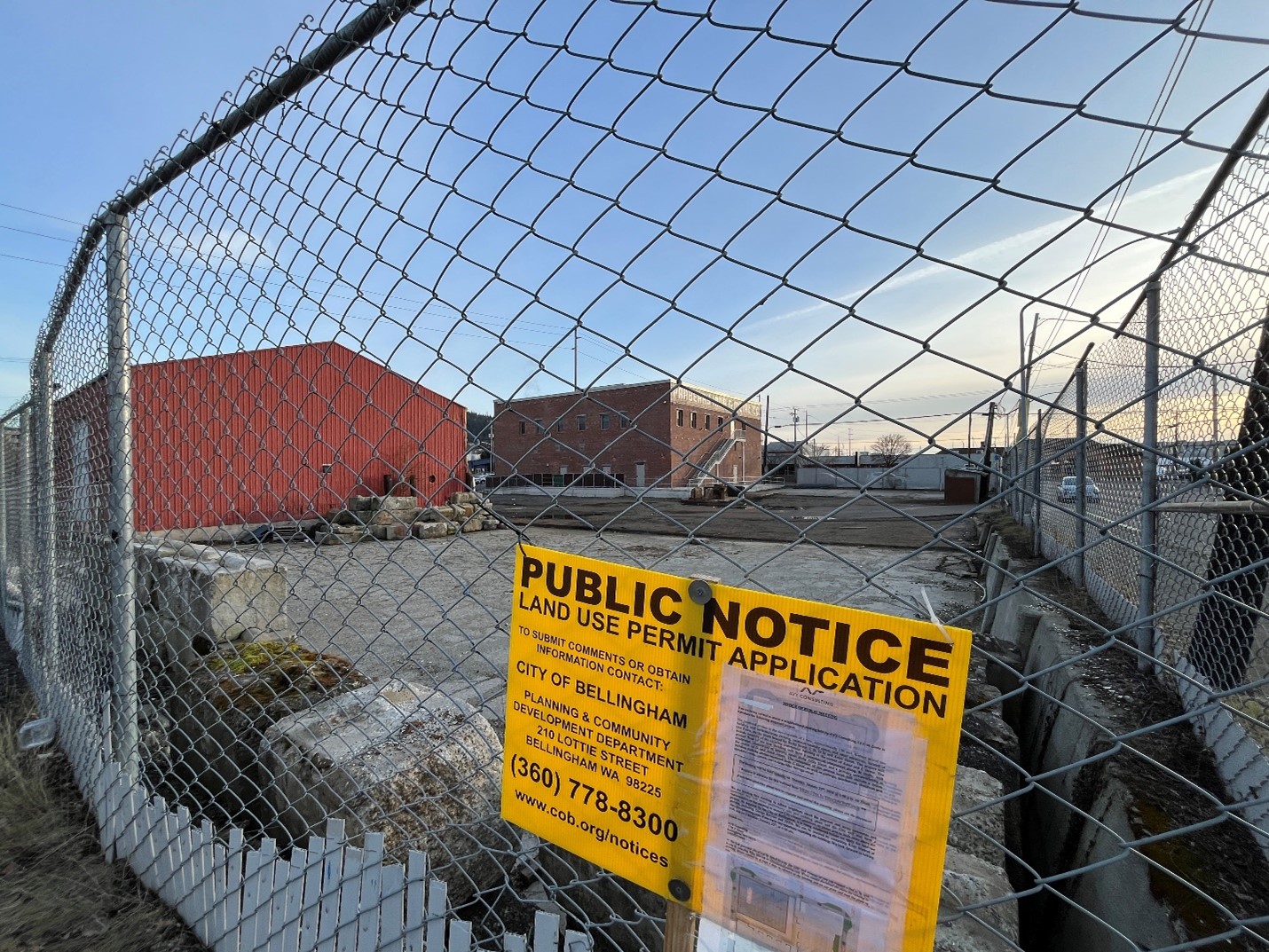

Bellingham’s industrial Old Town district is finally beginning its transformation into the walkable neighborhood city planners have long envisioned—thanks, in part, to a decision last year to try giving builders full flexibility over parking counts in that area.

The experiment has paid off. The first building proposed since the regulatory change will have more than twice the number of homes as would have been allowed last year.

“The shift to no parking minimums was a clear win in this case,” wrote Ali Taysi, a land use consultant for the project.

The first building proposed since the regulatory change will have more than twice the number of homes as would have been allowed last year.

The six-story building, located on the former recycling facility at 707 Astor, will house a mix of 84 studio and one- and two-bedroom apartments, with 1,600 square feet of commercial space on the ground floor. Permits are expected to be filed in May, with builders hoping to break ground early next year. The project is likely the first of several coming to the neighborhood, after the city signed a development agreement in 2023 for the eight city blocks that used to serve as scrapyard.

Now, the parking reform is being considered citywide.

Unlocking the potential of Old Town

Old Town’s transformation from industrial scrapyard to walkable mixed-use neighborhood has been anticipated since 2008 when the area was designated as the city’s second “urban village,” after downtown. At the time, planners estimated that 1,100 homes could be added there by 2022. Today, only 44 have been built.

The Parberry family, who first started salvaging metals along Whatcom Creek in 1923, owned 46 percent of developable land in the district, or about eight city blocks. Their initial plans to relocate the recycling facility were scuttled by the 2008 recession, but in recent years they discontinued their Old Town operations.

Building in Old Town is no easy feat. Decades of dumping refuse along the tidal mudflats of Whatcom Creek created 13 acres of landfill by the 1950s. The Department of Ecology remediated the area in 2005, removing tons of solid waste and capping the remaining contaminated soil. Excavation work can be prohibitively expensive, and restrictions on ground floor living and daycare centers remain in place. Future residents will also have to contend with the freight trains that run parallel to the district that sound their horns throughout the night.

But at a Planning Commission hearing on April 20, 2023, it seemed like Old Town’s future might finally have arrived.

“I wish it would have happened a little bit quicker,” said Tara Sundin, Manager of Community and Economic Development for the city. “But I’m just thankful that we have people that have been willing to come forward into one of our riskier parts of town.”

Developers Curt O’Conner and Pete Dawson, who both grew up in Bellingham, have paired up for the undertaking by purchasing all but one of the Parberry properties.

A parking reform pilot takes shape

To make building in Old Town feasible, builders proposed changes to the zoning code with the local Planning Commission. One modification was reducing parking mandates to be consistent with the city’s other urban villages. Instead of mandating a parking spot for every studio apartment, for example, the city would only require one parking space for every two.

“The conversation on ‘no parking minimums’ hadn’t really crossed our radar,” said Taysi, the developers’ consultant. “We thought it might be a bridge too far.”

Members of the planning commission, though, thought Old Town might be the perfect place to give builders full flexibility over parking. “This could be an opportunity to try to go further,” Commissioner Rose Lathrop proposed.

Another commissioner, Mike McAuley, agreed: “If we want to pilot something, this would be an amazing place to do that,” he said. “If we’re forcing the market to pay for a $60,000 parking space, all that does is provide car storage, right? It doesn’t provide more space for humans; it doesn’t provide more space for businesses; it doesn’t promote economic activity that we want to see here.”

The Commission voted in favor of eliminating parking mandates for Old Town by a 4–3 vote. City Council approved the change in June with support from the Whatcom Housing Alliance and Walk and Roll Bellingham.

Total flexibility pays off with more homes

Dawson & O’Connor have run with the idea. The latest design for the six-story building has 84 new homes with 36 parking stalls.

That’s more homes (and less parking) than would have been allowed under both the old code and the proposed reduction initially presented to the Planning Commission in April 2023. The same building would have needed 84 parking spots under the old code (1 parking spot per home) and still fully 59 parking spots under the proposed reduction.

The small site would have been hard pressed to find more space for parking.

“Thirty-three is about the max parking we can get on site,” Taysi said back in February. Architects were ultimately able to squeeze in a few more: 20 parking spaces will be tucked under the building, accompanied by a 16-vehicle surface lot. To add any more parking, the building would have needed a multilevel garage. In addition to the site’s soil contamination issues, parking garages are already more expensive than they’re worth in the Bellingham market. “We just don’t have the rents to support that,” said Taysi.

More likely, builders would have had to axe the number of homes to just 36 under the old code, or 50 under the proposed reduction, assuming they kept the same mix of studio and one- and two-bedroom apartments.

Now, thanks to the rule change builders are free to provide the mix of home sizes they think people need, and the burgeoning neighborhood gains twice as many apartments.

The lower parking space-to-home ratio is also a bit of an experiment for the builders. If people aren’t interested in moving in because of a lack of parking, there are multiple options to make up the difference. They could repurpose another vacant lot as an interim parking lot or increase the amount of parking in the next building.

“One of the reasons they’re willing to be so aggressive on underparking the building is because they own other properties in the district,” Taysi explained. Or, if parking demand turns out to be even lower than they’ve built for, the 16-car surface lot could transform into another building as the neighborhood grows.

The start of further parking reforms?

Old Town’s parking pilot has sparked a larger conversation about the role of parking mandates in Bellingham. How many little Old Towns might be scattered around the city, sitting underused, in part because of needlessly high parking mandates?

In February 2024, city council directed staff to study possible outcomes of removing parking minimums citywide. A work session on the topic is scheduled for later this May.

“There are three basic uses for land that we have: places for people, namely housing; places for trees; and places for cars, namely parking,” said Council Member Hollie Hutham, who introduced the motion in February. Amid council’s express support for more affordable housing and tree canopy coverage, Huthman urged a conversation “about how parking for cars fit into that equation.”

Council Member Jace Cotton also voiced support for citywide reform: “Eliminating parking minimums alone is obviously not going to solve the housing crisis. But it does constitute a necessary step in order to get to that end goal.”

Comments are closed.