Takeaways

- The Karuk people, whose homelands straddle the California-Oregon border, hold millennia-old cultural burning knowledge and practices that support their food, health, spiritual, and cultural traditions as well as local ecosystems.

- The Tribe emphasizes that respecting Tribal sovereignty is key for Karuk cultural burning, and burning is key for Tribal sovereignty.

- A proposed policy in California, SB 310, would acknowledge Tribes’ cultural fire practices, respect fire practitioners’ right to burn, and shift a hierarchical relationship with California to be sovereign-to-sovereign with respect to burning.

- Indigenous co-stewardship of national forests is benefitting Tribal culture, non-Indigenous people, and forest ecosystems. For the Karuk Tribe, co-management would be even better.

- These policies are steps toward unlearning the idea that the United States “gives rights” to Tribes and re-learning that sovereign Tribes hold those rights intrinsically.

“The piece that is misunderstood about Indigenous cultural fire is sovereignty.” That was one of the first things Bill Tripp, director of Natural Resources and Environmental Policy for the Karuk Tribe, said to me when I interviewed him for Sightline’s research series on wildfire solutions.

Each year, wildfires cost the United States tens to hundreds of billions of dollars. Policymakers are finally acknowledging what Indigenous peoples have been saying for decades: most forests need more fire, not less. Government agencies are scrambling to reverse the dominant paradigm of aggressively suppressing wildfire and its legacy of fuel-choked forests primed to burn. This includes recognizing the role of Indigenous land stewardship and extensive burning. Importantly, this shift is also a doorway to that larger issue Tripp named: sovereignty.

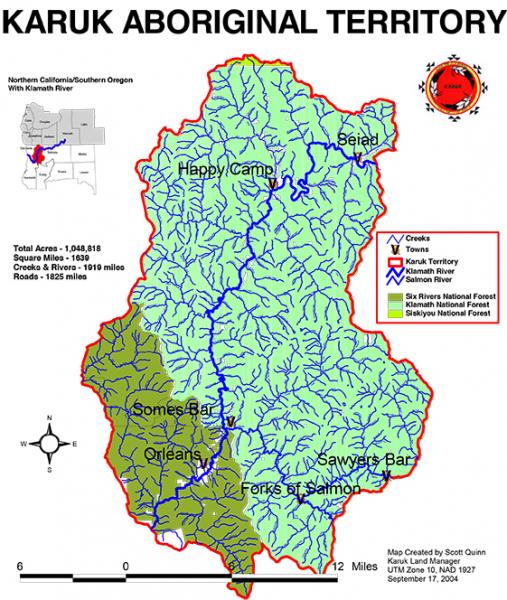

This article explains the relationship between cultural burning and Tribal sovereignty for the Karuk1 Tribe, whose homelands straddle the California-Oregon border.2 It describes recent wins in their struggle for others to understand and recognize their sovereignty—specifically new policy in the California Legislature and agreements with the US Forest Service that clarify who has a right to burn and where. Interviews with Tripp heavily informed the discussion below.

Karuk fire traditions undergird their sovereignty

For millennia, like other Native Americans across the United States and Canada, Karuk people have used fire to tend their homelands as an abundant garden landscape.3 This article limits its focus to the United States because despite much overlap with Canada, the two countries’ legal approaches to fire and First Nations are different.

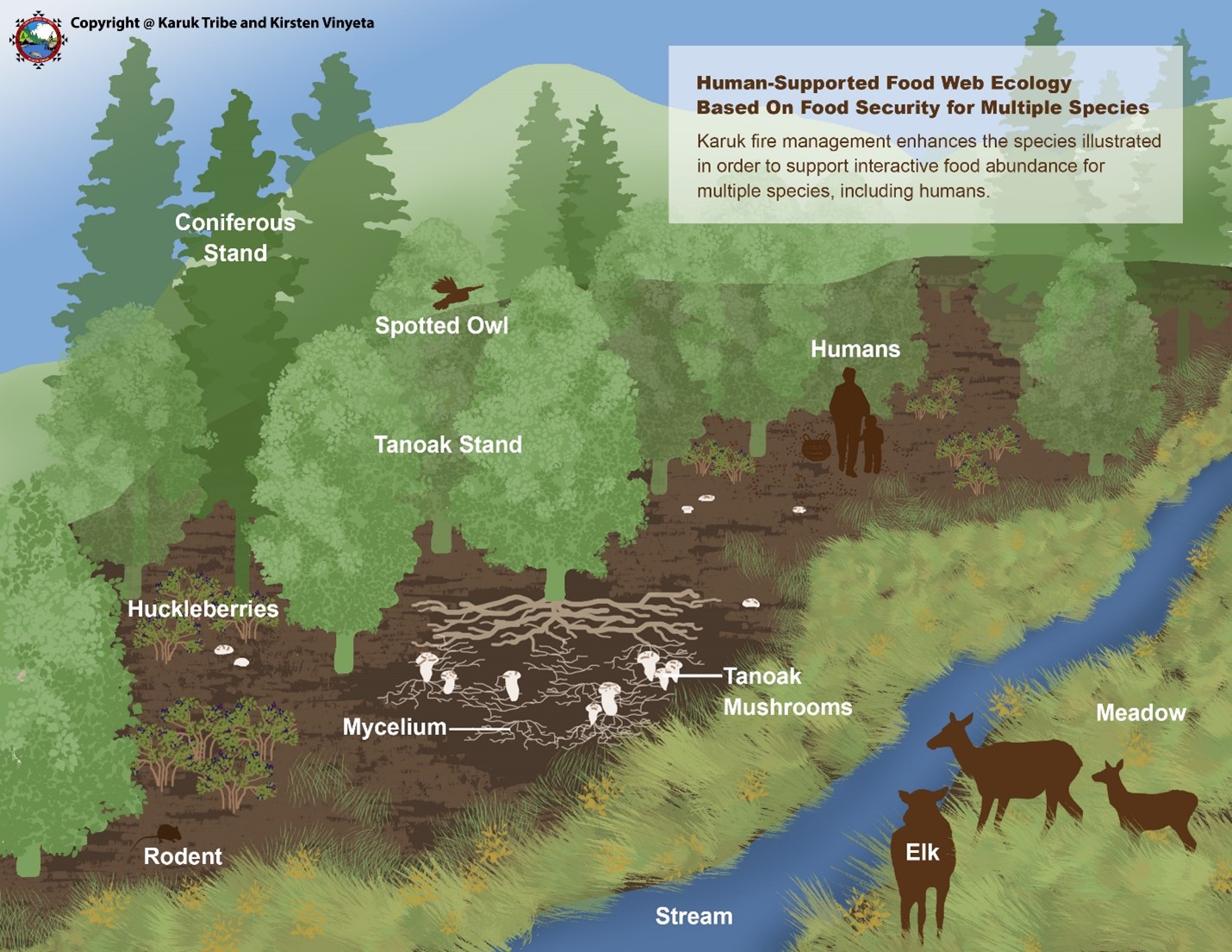

They burn to cultivate tanoaks, acorns, mushrooms, hazel, and elk habitat, to name just a few of the hundreds of species that together support Karuk ways of life. And, along with lightning-sparked ignitions, their low-intensity fires clear out understory ladder fuels that could otherwise kindle severe wildfires that could wipe out their communities.

Colonization, genocide, and ensuing assimilation as well as forest management policies, however, shifted the forest from being productive for people and wildlife to being productive for timber.4 For more than a century, state and federal laws essentially outlawed Indigenous burning and mandated immediate suppression of natural ignitions. Law enforcement could jail Native people caught burning. Many people still hunt, fish, and gather, but without fire, the habitats and species that are central to Karuk ways of life have significantly diminished.

Hence, even to the degree that the Tribe can make and enforce its own laws and take other actions of self-governance (legal sovereignty), repressing fire has significantly impacted their cultural sovereignty and forced many to assimilate into store-bought foods and Western culture. Karuk cultural biologist Ron Reed explained that “without fire, the landscape changes dramatically. And in that process, the traditional foods that we need for a sustainable lifestyle become unavailable…so we’re not getting the nutrition that we need. We’re not getting the exercise that we need.”

For food, health, and spiritual connection

Huckleberries, for example, are a first food whose phytochemicals and micronutrients may help prevent cancer and diabetes and may aid eye, heart, and cognitive health. Regular burns boost huckleberry productivity by clearing competing vegetation, opening the canopy to let in more sunlight, releasing nutrients into the soil, removing overgrown branches, and spurring the growth of new shoots. In the past, regular cycles of burning yielded bountiful harvests of two to eight gallons of berries per person per day.

But stewarding first foods and fibers yields more than nutrition and exercise; it also nourishes the spirit and community. As Reed articulated,

[Without fire,] the reason we are going back to that landscape is no longer there. So the spiritual connection to the landscape is altered significantly. …When we don’t go back to the places that we are used to, accustomed to, part of our lifestyle is curtailed dramatically. …Your mental aspect of life is severed from the spiritual relationship with the earth, with the Great Creator. …And we’re not replenishing the spiritual balance that creates harmony and diversity throughout the landscape.

More than “prescribed fire”

Cultural burning can be much more than fuels reduction. The Karuk Tribe is working to educate that “while cultural burning shares some limited similarities with prescribed fire, it is a wholly separate practice governed by Tribal and natural laws.”

Indeed, its use goes beyond the traditional foods and wildfire benefits that academics, policymakers, and popular culture are starting to associate with Indigenous cultural fire. Cultural burning is a dynamic practice that Native people continue to adapt in response to new circumstances, from climate change to shifting land use patterns. An example may help demonstrate the point.

Example: The game of sticks

Tripp told me that his most recent cultural burn was to clear star thistle from the fields the Tribe uses to play the game of sticks. Sticks is a three-on-three game played for fun and for training strong, strategic, and nimble youth. It’s like a cross between rugby, football, and lacrosse.

Star thistle wasn’t around when Tripp’s ancestors were playing sticks. It’s a more recent nuisance that plagues landowners across the West. Mowing just intensifies its root production, and turning over the soil breaks the roots into fragments that grow into new plants. Petaluma-based rancher George McClelland told me, “I’m breaking my back all day pulling thistle. It’s going to send me to an early grave.” He can’t use the herbicides that kill thistle because his dairy operation is organic.

But fire is a solution. If you burn before the star thistle has matured enough to produce good seeds but after the native grasses, which mature more quickly, have dried up and dispersed their fire-resistant seeds, the dry native grasses then provide the tinder needed to burn the still-green thistle. Tripp explained,

You don’t want all that dead dry pokey thistle with people out there wrestling around. You don’t really want to be tackled into a thistle stick that can poke you in the eye or something. Burning all that stuff up is the best way to maintain that cultural space for that cultural practice, and so me and my brother burned in June last year.

We started out in an area that has been really choked up with star thistle. It’s an invasive species that travels in by roads and foot traffic, and it just grows like crazy. But it’s one of those species that if you can burn it right in that window when the native grass seeds are viable but the thistle seeds aren’t viable yet, and if you can do that three years in a row with fire, the fire will end up flushing the seeds. Just mowing won’t flush the seeds, but burning will.

We got Council approvals and got our cultural fire practitioner to come out and lead that burn. We burned it at night. We picked our starting point based on our local conditions in the evening, and we just worked our way around the stick field slowly, just burning off about 20 feet and then putting it out as we went. Once we got a black line all the way around the field, then we just used whatever winds were available to carry the burn inside that perimeter.

It was really effective. It wasn’t a massive fire happening all at one time, and we didn’t light anything that we couldn’t put out. The fire was sending embers into dry grass across the feature that we had for holding it there, which was a road. But the humidity comes up so high at night that time of year that the potential for those embers to light a fire is pretty low. It went off without a hitch.

The Karuk people continue to adapt the powerful tool of fire to precisely—and sustainably—shape their ecosystem.

Redefining the who and what of cultural burning

Tripp had an approved plan and a permit for his sticks fields burn, and he has the qualifications of a professional wildland firefighter. But Tripp explained that the Tribe does not need these state requirements because it retains the right to self-govern burning. Despite these rights, according to Tripp, local law enforcement has continued to harass cultural fire practitioners, creating risks that disempower cultural burners and restrain growth in their numbers. He said,

Individuals do get harassed a lot. It’s one of those things that has a major spotlight on it. For a lot of years, people just turned their heads. But there are individuals, more recently, that started calling things in whenever there’s a slight smell of smoke. And so you never know who’s going to come from where and how they’re going to interpret the law to be. …They have a fire engine showing up saying, ‘Who started this fire? We’re going to arrest you if we find out who it is.’ Even in February when [the fire is] not going anywhere.

After years of work, the Karuk and other California Tribes are achieving policy wins that help resolve these risks. The state is starting to recognize Tribes’ sovereign authority to self-govern their own cultural burning, namely through two laws intended to encourage more beneficial fire by non-government groups and a third bill, currently working its way through the California state house, that would take Tribal sovereignty to the next level.

AB 642: Distinguishing from prescribed fire

For the first time in California history, Assembly Bill 642, passed in 2021, defined the terms “cultural fire practitioner” and “cultural burning,” officially recognizing cultural fire as distinct from prescribed fire and acknowledging that cultural burners need to be treated differently.5 The law also requires the director of the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (CAL FIRE) to appoint an Indigenous cultural burning liaison to, among other duties, serve on the State Board of Fire Services and to advise on increasing cultural burning activity.

SB 332: Establishing protections for cultural fire practitioners

In the rare event that a controlled burn escapes, Senate Bill 332, also passed in 2021, shields burners not deemed grossly negligent from liability for the state’s expenses to suppress the fire. The bill exempts cultural burners from the law’s requirement that eligible burns follow a written burn plan approved by a state-qualified burn boss.

This means, for example, that Karuk community members can be protected from firefighting expenses even if they lack the qualifications that are mandated for other burn practitioners. Tripp explained why this is important.

We need to be able to have our community be the community it’s meant to be in this place. And a lot of our Tribal folks are simply not going to get the qualifications. They’re not going to go on wildfires, so they can’t get into all the NWCG [National Wildfire Coordinating Group] training. But they want to take care of the place around where they live, and they’re more than capable of doing so.

SB 310: The next chapter for Tribal sovereignty in fire practices

Unfortunately, SB 332 fell short of aligning with Tribes’ right to self-govern burning. According to Sara Clark, an attorney involved in negotiating the new policies, “It was a meaningful step for the state to recognize that cultural burners aren’t going to have a written burn plan and they’re not going to use a state-qualified burn boss. It just didn’t get the whole way there.”

For example, SB 332 does not exempt cultural burns from needing a burn permit, which CAL FIRE gatekeepers can deny, or an air quality permit. According to Colleen Rossier, senior research and policy advisor for the Karuk Department of Natural Resources, “These are direct affronts to Tribal sovereignty.” And if they burn without an approved burn plan and permit, they forfeit access to the state’s Prescribed Fire Claims Fund, established in 2022, which pays up to $2 million per incident for damages to private property.

“Ultimately, there’s still this administrative or authoritative power grab over the burn process,” Tripp said.

The Karuk Tribe supports Senate Bill 310, currently near the finish line in the California legislature, which would explicitly recognize Tribal sovereignty with respect to cultural burning. This bill would authorize the California Natural Resources Agency to enter into sovereign-to-sovereign agreements with California Tribes that would acknowledge that state laws and regulations do not apply to cultural burns and would include eliminating burn permits and other permitting and regulatory requirements.

Tripp said, “SB 310 is intended to kind of pull out all the stops and say, ‘Hey, this is a sovereign authority.’”

Redefining the where of cultural burning

Besides who can burn, the Karuk Tribe has also struggled for sovereignty over where it can burn. In this regard, too, it has achieved important success. The Tribe wants acknowledged decision-making authority to co-manage its ancestral lands. This includes using fire to restore more than one million acres of conifers, oak woodlands, and grasslands now under both Tribal jurisdiction and the jurisdiction of the Six Rivers and Klamath National Forests, according to Rossier.

The Tribe is equipped for this role. For example, the Karuk Tribe Department of Natural Resources maintains an actionable restoration and climate adaptation plan and an eco-cultural resource management plan based on a combination of traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) and Western science. The plan documents how to use fire to restore habitat for the Pacific giant salamander, black oaks, and twenty additional indicator species, including where to ignite, what natural features act as fire breaks, which habitats cover different micro-climates, and the time of year for initial burn and follow-up burn.

Co-stewardship with the US Forest Service

After years of effort, including plenty of setbacks, the Karuk Tribe has secured a recognized co-stewardship role with the US Forest Service. Collaborating through the Western Klamath Restoration Partnership, the Tribe co-created a plan to restore fire resilience to a 1.2-million-acre landscape that largely follows the boundaries of its aboriginal territory. Specific projects are based on both Karuk fire practices and priorities, such a TEK carried in the story of how Coyote stole Fire, and the goals of the United States National Cohesive Wildland Fire Management Strategy.

Tripp described the Tribe’s progress in its relationship with the US Forest Service:

It seems like we’re starting to get to a place where we are really able to communicate the hard truths as everyone sees them. And not be offended by it. We’re able to say, “Okay, well, where is the common ground? Where is the shared value? How can we just put this other stuff aside and do things that achieve the shared value and the collective vision?” And we’re getting there, slowly but surely, on about half of our territorial landscape. And the conversation is starting to shift on the other half of that Forest Service Unit as well.

More coordination has allowed more burning. Tripp spoke about a large restoration burn in summer 2023:

This past June turned into an all-hands-on-deck situation, and we were able to collectively pull off a 135-acre burn. I mean, that is unheard of. All the stars aligned, and we were able to integrate the Tribe, the Forest Service, and local partners to do a wildland fire management project. We had Tribal staff out there that were in leadership roles in that burn, and we would alternate who’s doing what, who was getting training assignments. And it just turned out great.

When you look up at that landscape today, you see very few scorched trees on that 135 acres, and a lot of the area that had really thick duff that’s prone to high severity fire—a lot of that was consumed, so that risk has been reduced significantly. And now, if we can put that place back into a regular frequent fire interval, that risk can potentially be mitigated in perpetuity as we expand fire to the broader landscape.

Expanding from co-stewardship to co-management

Many Tribes and some federal agencies use the term “co-stewardship” to describe the kind of collaboration occurring between the Karuk Tribe and the US Forest Service. But what the Tribe ultimately aspires to and is working toward is “co-management.” Tripp described the distinction:

Co-stewardship is more just collaborating on projects but not necessarily shared decision-making, whereas co-management is more of a shared decision-making relationship. So we are currently progressing in the co-stewardship arena, but we are trying to reach equal footing with states and the federal government on having that equal say in shared decision-making.

There are only a handful of nascent examples of co-management between the United States and a Tribe, so Tripp could only speculate on what form it would take on the Karuk’s aboriginal territory.

In our case, maybe that’s a compartmentalized decision-making process. Maybe the Tribe makes decisions on cultural burning and the Forest Service makes decisions on prescribed fire. Maybe that means that we’re both signing NEPA [National Environmental Policy Act] documents. Maybe that means that we make decisions about what our Tribal members do and what our programs do, and the Forest Service is making decisions over what their programs do. Maybe we’re making decisions over a portion of what the federal program is.

One win at a time

Achieving co-management may appear to be a longshot, but the Karuk Tribe is winning one small victory after another. It is working strategically and patiently, and its recent successes in the California legislature demonstrate that longshots are possible.

Recently, Tripp served on the influential Wildland Fire Mitigation and Management Commission, co-authoring the most comprehensive recommendations to date for overhauling every facet of the United States’ approach to wildfire. Recommendations #30 and #141 suggest that Congress authorize the US Forest Service to enter into co-management agreements with Tribes, allowing shared or transferred decision-making authority, and recommend a blue-ribbon panel to identify how to reduce co-management barriers.

One of the Karuk Department of Natural Resources’ highest priorities is to ensure that all the recommendations in the report are faithfully implemented.

Sovereignty: Unlearning colonial definitions for a healthier fire future

The United States largely recognizes Tribal sovereignty and interacts with Tribes as one government to another. But the details are complex and constantly shifting. The last significant Supreme Court decision to revise the interpretation of Tribal sovereignty was as recent as 2022 and decided by a slim five-to-four majority.

The US government initially recognized Tribes as independent nations, but an 1831 Supreme Court decision redefined them as “domestic dependent nations,” making them accountable to federal law. Subsequent (and contested) federal law made Tribes in certain states, including California, subject to certain state laws as well.

Each Indigenous nation has a unique history of land occupation, treaties, and recognition (or lack thereof) by the United States. But greater recognition of Tribal sovereignty across these diverse circumstances is a common cause, and to varying degrees, wins for one Tribe can influence the interpretation of sovereignty for others.

Sovereignty for the Karuk

For Karuk people, sovereignty has many meanings. It can be understood to have a legal meaning (an independent, self-governing nation) and a cultural meaning. It entails access to, responsibility for, and stewardship of the plants, animals, lands, and waters the Karuk people live their culture and traditions through.

Unfortunately, this access has long been denied, and with it, the continuation of those traditions. Many Karuk people believe that if they can’t actively manage their homeland; continue to observe and refine their knowledge, practice, and belief systems; and restore species balance with fire, they will continue to lose their culture, with continuing and increasing negative impacts on the local ecosystems.

If certain critical actions are taken, however, strengthening Tribal sovereignty may be a powerful positive change both resulting from and constructively addressing the worsening wildfire crisis and other environmental crises, which in many cases may have been averted had Indigenous Knowledge and collaboration been embraced earlier. According to a Karuk report titled Retaining Knowledge Sovereignty,

Interest in Tribal TEK creates a relatively supportive political environment that can be conducive to a return of traditional management activities—thereby benefitting Tribal culture, non-Indian people and forest ecosystems.6

As discussed above, the Karuk Tribe has embraced this opportunity to advance its long-term struggle for Tribal sovereignty. The Tribe has pushed the California legislature to pass several laws that recognize cultural burning and empower cultural fire practitioners. It has secured co-stewardship agreements with the Six Rivers National Forest that occupies its aboriginal territory. And it has become a key contributor to state and national wildfire policy development.

“No, Tribes have those rights.”

“We are constantly using language around ‘giving rights’ or ‘giving authority.’ You have to unlearn first, to be able to really say, ‘No, Tribes have those rights.’ The federal government literally has to do nothing for those rights to exist. Those rights exist.” -Sara Clark, Attorney

In the big picture of addressing the historic injustices inflicted by the United States and state governments on Native Americans, the Karuk Tribe’s fire management victories—in the California legislature and with the US Forest Service—may seem small. Tripp assured me that “these wins don’t change legal precedent about Tribal sovereignty.”

Still, they are meaningful. The California legislature’s clear acknowledgement of Tribal sovereignty and its rulemaking to protect incursions on that sovereignty sets a new national standard in the constantly shifting interpretation of that concept in the United States. It also invites a profound cultural shift in mainstream understanding of Tribal sovereignty.

The potentially game-changing significance of SB 310, in addition to reorienting cultural burn decision-making relationships to be sovereign-to-sovereign, is for more people to understand, acknowledge, and recognize that the Karuk Tribe has sovereignty. “It’s a real linguistic challenge, the unlearning we have to do,” Clark, the attorney, said. “Lawyers learn how the federal government and state governments work. But we are not taught that Tribes are sovereign entities. So we are constantly using language around ‘giving rights’ or ‘giving authority.’ You have to unlearn first, to be able to really say, ‘No, Tribes have those rights.’ The federal government literally has to do nothing for those rights to exist. Those rights exist.”

Doing this research, I also had to unlearn. I asked Tripp, “What are the concrete legal changes that would help win Tribal sovereignty?” He patiently explained:

We don’t need to win Tribal sovereignty; we need to acknowledge that Tribal sovereignty exists. We’re starting to do that in California. But that’s more about creating a legislative process that enables an agency to do something that they currently perceive as not possible but is entirely possible. They just don’t understand how it’s possible.

Comments are closed.