Takeaways

- Parking mandates—i.e., requirements that every new home or business have a pre-determined number of parking spaces—thwart small-scale homebuilding projects the most, because they have neither the space nor spare funds for unnecessary parking.

- Leaders in various jurisdictions have legalized middle housing types like triplexes—but if they hope to see to them actually built, parking mandates have to go.

Find audio versions of Sightline articles on any of your favorite podcast platforms, including Spotify, Google, and Apple.

In January 2024, the Washington Department of Commerce published model ordinances for cities that will be updating their zoning codes to include new state-legalized “middle housing,” from duplexes to sixplexes to cottages clustered around a shared courtyard. But when it came to parking minimums, the model ordinances sidestepped best-in-class policies to defer to status quo politics. In other words, unless your property is near a major transit stop, the state still recommends one or two parking spaces for every new home.

That’s a problem, because between small lot sizes or navigating around an existing house, even one more parking spot is a bar that many middle housing projects just can’t clear.

Daniel Parolek, who coined the term “missing middle housing,” has been saying this for years. “Requiring off-street parking has the biggest impact on small-lot residential infill,” Parolek wrote in his book Missing Middle Housing. It’s no surprise, then, that it’s the jurisdictions where off-street parking is voluntary for new backyard cottages that they’re sprouting up left and right.

To truly restore the right to build a diversity of housing options, from duplexes to a mother-in-law apartment over the garage, cities need to free these future homes from the tangle of regulations governing parking spaces.

On small lots, parking can be a big problem

The problem with mandating off-street parking comes down to basic geometry. Cars take up a lot of space.

For lots 7,500 square feet or smaller, Parolek writes, “the space needed to fit off-street parking on the site typically makes it physically impossible to provide the required amount of parking and get multiple units on the site. If an architect can make the parking fit, oftentimes there is not enough development potential to make the financial sense to pursue.”

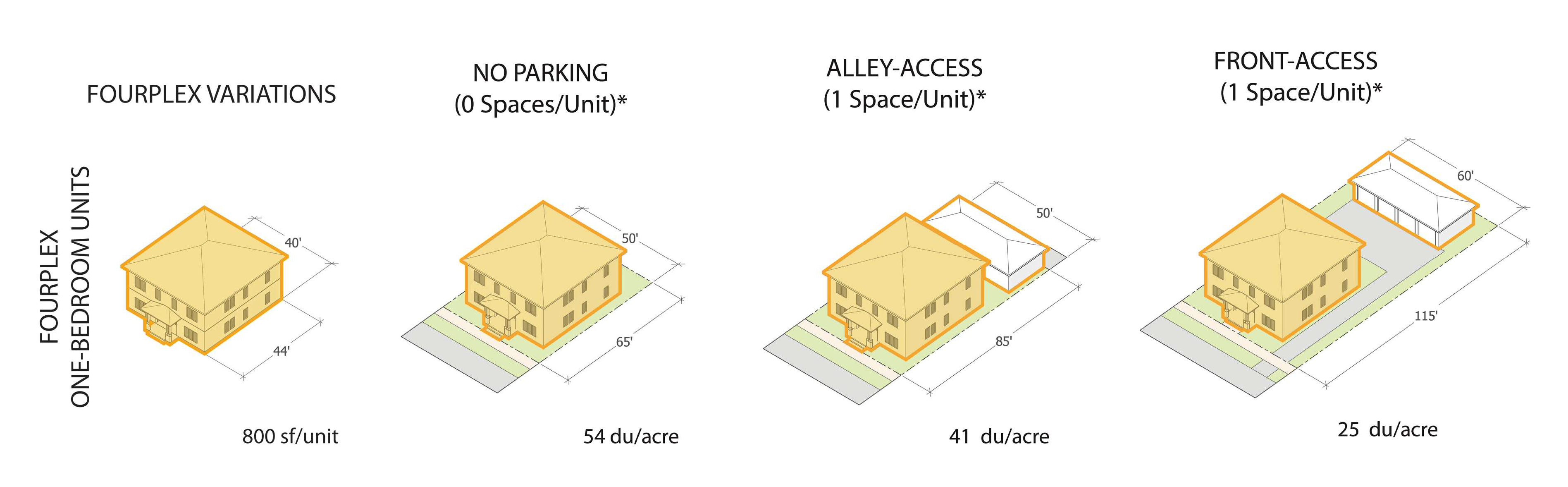

Parolek illustrates the difference. To make way for four parking spots, a future fourplex would need a parcel of land twice as large as the same fourplex without any off-street parking.

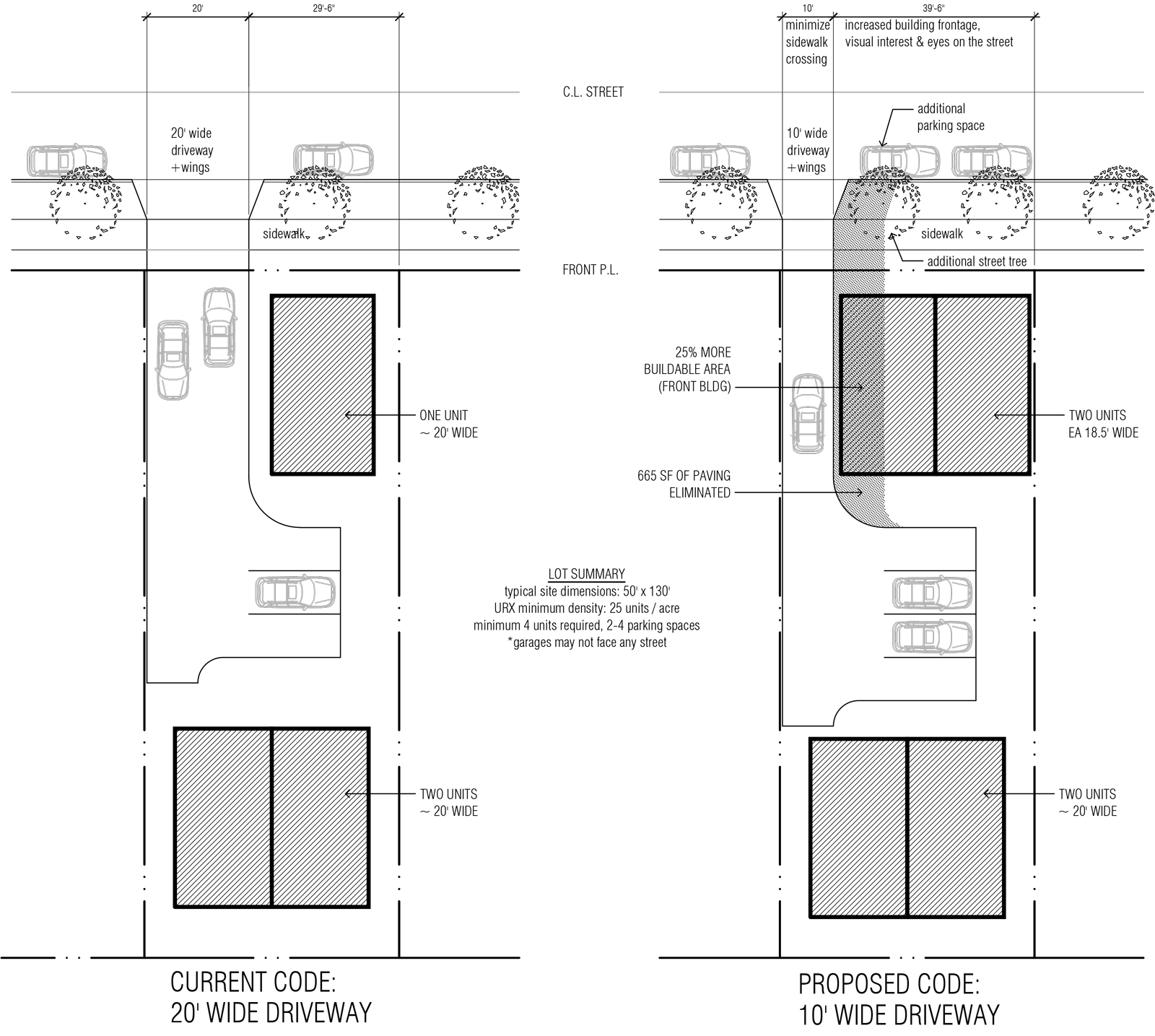

The real estate needed to park a car far exceeds the asphalt it sits atop. Driveways and additional space for a car to turn around on-site take can cover a large fraction of a lot’s buildable area. David Foster, an architect in Tacoma, Washington, illustrated how just reducing driveway widths from 20 feet to 10 feet could grow a housing project from three homes to four, even while maintaining a parking space for each one.

When designing around an existing home, even finding room for one more parking space can be an impossible task. Last year, when Kent, Washington, was updating its zoning codes for accessory dwelling units (ADUs, a.k.a. backyard cottages or granny flats), it made a startling discovery. Eighty-five percent1 of single detached homes couldn’t build an ADU because of the additional parking space required—one reason why less than 30 of these lower-cost housing options have been built there since 1995. Regulations on parking location, driveway widths, and curb cuts all ate away at possible parking options until they devoured the feasibility of a new home.

![Greenfield_Park_Parking_Restriction_Analysis The majority of residential properties [in orange] in Kent’s Greenfield Park neighborhood cannot add the one parking space required for an accessory dwelling unit. Image by Cast Architecture. Used with permission.](https://www.sightline.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/Greenfield_Park_Parking_Restriction_Analysis.png)

With most homeowners unable to physically add parking, the city changed course instead. By reversing a policy of not counting garage spaces towards the parking requirement, homeowners found themselves with double the number of legal parking spots overnight. No bulldozers required.

The secret ingredient to abundant backyard cottages? Parking flexibility

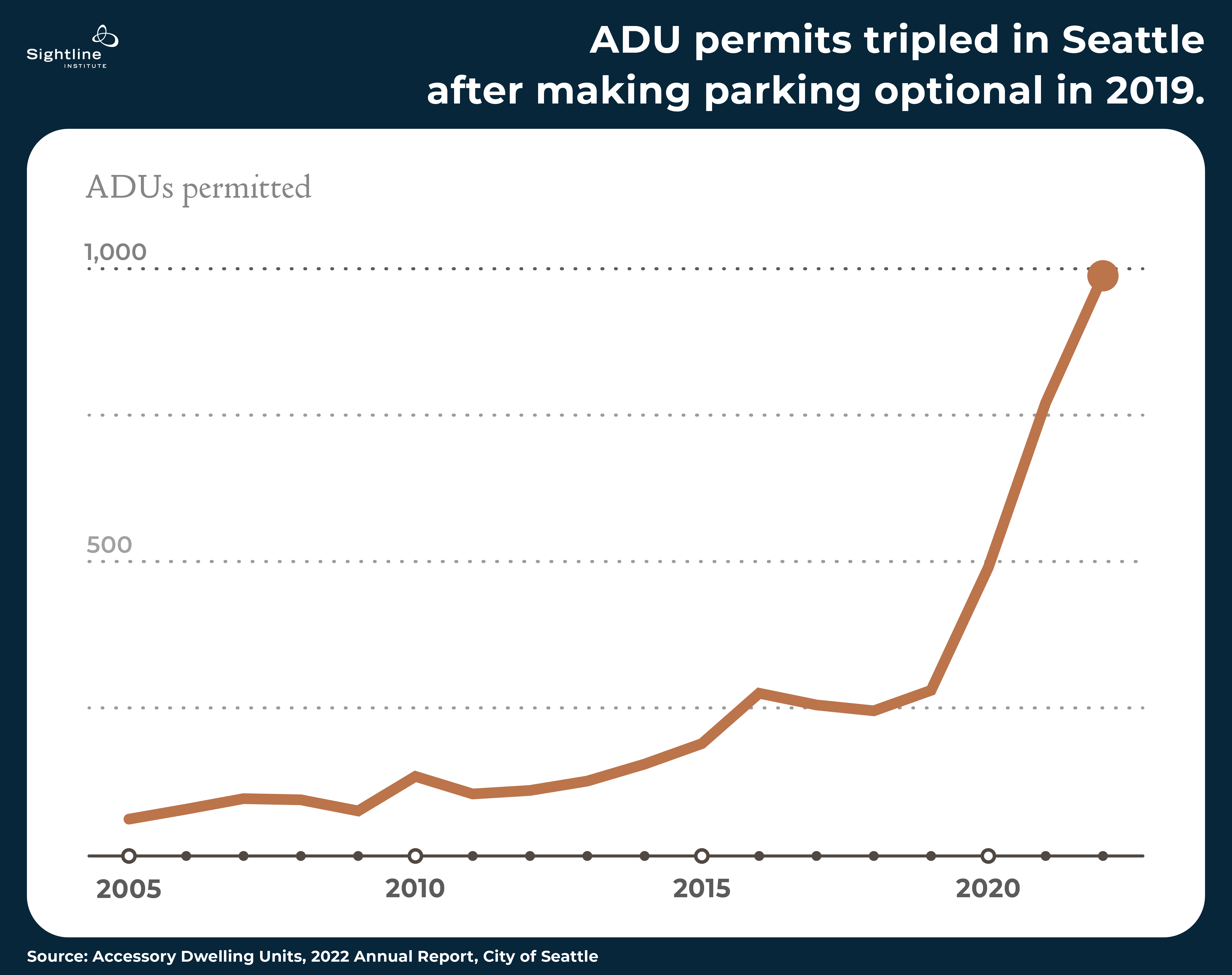

In place after place that has granted flexibility over parking, property owners have taken up the opportunity with gusto. For instance, since Seattle eliminated parking mandates for backyard cottages in 2019, permit applications have more than tripled.

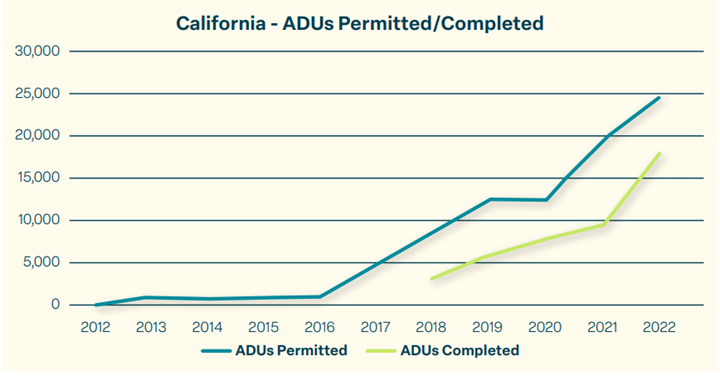

Meanwhile in California, one in seven new homes is now an ADU. Between 2016, the last year Golden State cities could require parking for all ADUs, and 2022, permits for these more budget-friendly dwellings increased over 15,000 percent. And though California has not lifted parking minimums for ADUs outright, the list of exceptions (homes near public transit, in historic districts, no replacement parking required for garage conversions, etc.) covers a vast swath of properties.

Prior to Seattle’s code change, the requirement to create an additional parking space for a new backyard cottage killed most potential projects, recalled Erich Armbruster, an infill builder in Seattle. “It’s not just a place where a car can park; it’s a code-compliant parking space.” On a lot that is 40 or 50 feet wide, there just wasn’t room to get a car past the existing house to the backyard. Only once, Armbruster could recall, was a neighbor willing to sell a few feet of their abutting yard so a homeowner could make room for a driveway. “After the 2019 code passed and we could just have one parking stall per site [total], it became much more feasible to do this. It really unlocked our ability to build.”

One of the first to utilize the 2019 code change that nixed the parking mandate for ADUs in Seattle was Mark Mohrlang’s family. As a pastor, Mohrlang knew people who struggled with housing and that Seattle lacked affordable options. The extra income could also help support his growing family, as his wife was then pregnant with a second child. Mark and his wife had already started scoping the home’s feasibility as the ordinance was heading towards city council. They decided to wait for the new rules, which allowed for a larger dwelling and made a driveway optional. This change, by which they could forego the driveway, also let them preserve the site’s large trees and instead provide a walking path to the gravel parking already in front. They broke ground in 2020 with a 3-bed, 1.5-bath home that they now rent to a single mother and her two children.

How much ‘middle housing’ will go missing because of parking mandates?

It’s difficult to know exactly how many ADUs go unbuilt because of parking mandates—or how many spring to life due to their absence. Optional parking is just one factor of many that makes middle housing feasible. Cities like Seattle typically amend multiple rules in one ordinance, so a perfect before-and-after comparison is impossible. However, a 2017 survey of California cities found that jurisdictions receiving ADU permit applications at least once a month were twice as likely to have no parking mandates than their peers who received applications less often.

“The middle-housing, ADU conversation is recent enough there isn’t a lot of data on this,” said Kol Peterson, author the book Backdoor Revolution, about building ADUs. Despite the lack of hard numbers, though, Peterson has no doubt that eliminating parking mandates is essential to unlocking more backyard cottages. “In the hundreds of ADUs that I’ve been to—I’ve probably been to 500—I’ve never once seen someone build an off-street parking spot.”

Planners from two Washington cities confirmed that, given the option, most homeowners choose not to add more parking while building an ADU. In Port Townsend, 7 of the 8 ADUs built in 2023 didn’t add a parking spot. Neither did 17 of the 24 ADUs permitted in Olympia in 2022.

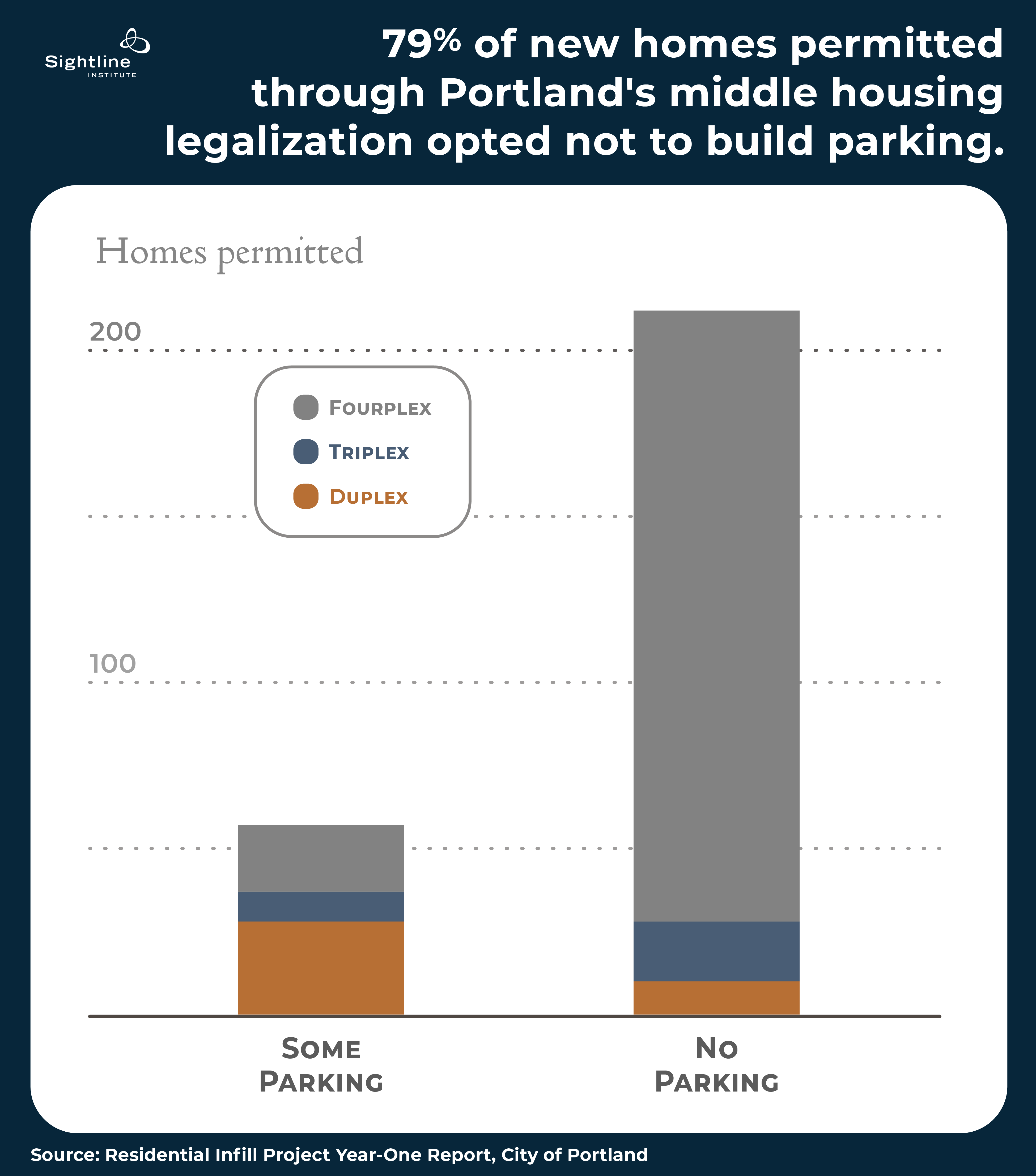

Portland, Oregon, is one of the few cities tracking how much off-street parking homebuilders have voluntarily added for duplexes, triplexes, and fourplexes, which the city legalized in 2021. Early data from the first year after the new rules went into effect indicated 79 percent of the new homes permitted forewent off-street parking, including the vast majority of fourplexes.

Barriers persist even when builders do want to add parking

Even when parking is fully optional, small-scale builders still wrestle with how to accommodate the parking they want to provide with codes that weren’t written with housing types in mind beyond the single detached house.

Thanks to Marc Daudon & Maud Smith Daudon for supporting a sustainable Cascadia.

Our work is made possible by the generosity of people like you.

“It’s not just the parking spaces themselves and the space that they consume, but all the public works improvements that come with that,” explained Ben Wharton, a homebuilder in Spokane, Washington. “Stormwater and alley improvements—those two things can burden a project so much that it becomes infeasible at a small scale,” he said. Detached homes are exempt.

These expenses recently scuttled a fourplex that Wharton was working on in Spokane. To build four family-sized units with a covered parking stall for each, the city was going to require his firm to improve the alley by paving it, a $90,000 expense. “We had to pull the plug and reassess,” Wharton said. “Any requirement is going to disproportionately impact small projects. If you have 150 units, you can absorb a lot of that [cost]. A 4-unit building can’t.”

Just keeping existing driveways can be a challenge, as local architect Dylan Lamar in Eugene, Oregon, found out. In Eugene, like in many cities, properties with three or more homes are subject to stricter rules governing parking location than a single detached house. That’s been a headache for one project he has underway that would add four new homes to the backyard of an existing house, one of which would be fully accessible.

When we initially spoke in June 2023, Lamar was considering applying for a variance to merely keep the driveway for the future tenant with accessibility needs. Having parking out front is fine for a detached house, according to city code, but as the number of homes increases, parking has to be located around back, out of sight. Without enough clearance between the house and the property line, no driveway to the back could fit. His options were to fight for this one space or have no off-street parking at all.

Lamar was spared that expensive and time-consuming process, though, by a technical detail. This driveway led to a garage, so the city didn’t legally consider it a parking spot in its own right—bad if Lamar needed to fulfill a parking mandate, but good in this case. His close call shows how local regulations have lagged behind statewide reforms in furnishing builders with the flexibility they need to open up more middle housing options for Oregonians.

Still, Lamar told Sightline last July, under Eugene’s 2022 city code that required an off-street parking space for every home, the project wouldn’t have had a prayer. State leaders’ action that legalized middle housing and made parking optional unlocked four more homes for Eugene families in Lamar’s project—and untold more in others since.

Getting it right: The middle housing–parking connection

The efforts to restore middle housing and lift parking mandates must go hand in hand.

Despite the Washington legislature’s laudable strides to allow more middle housing, the persistence of outdated parking mandates will continue to undercut homeowners’ ability to construct them. Even a small-sounding requirement for a couple of parking spaces can be impossible for small properties to fulfill. To unlock the full potential of small-scale homes, there is no policy debate: parking minimums have to go.

With each step towards parking flexibility, we move closer to building vibrant, sustainable communities where everyone has a place to call home.

Comments are closed.