Takeaways

In Alaska, Republicans, independents, and Democrats vote at about the same middling rates.

That means laws aimed at making it easier to vote have the potential to help Alaskans across the spectrum, not just one party or another.

Alaska legislators introduced packages of pro-voter measures in 2022 and 2023 in Juneau, including same-day voter registration, a cure process for ballots with minor errors, and postage-prepaid return envelopes for absentee ballots, but they didn’t pass.

With some of these measures up for consideration again in 2024, lawmakers still have the power to ease the voting process for all Alaskans: Republicans, Democrats, Independents, and everyone in between.

Find audio versions of Sightline articles on any of your favorite podcast platforms, including Spotify, Google, and Apple.

Conventional political wisdom says that laws to make voting more convenient help Democrats, but not Republicans. That doesn’t appear to be the case in Alaska, where voters across the political spectrum would stand to benefit from policies that smooth the way to casting their ballots.

Why does this matter? Because the Alaska legislature can still mobilize to get a big voter access bill over the line in 2024, after two consecutive years of attempts. But the sticky false narrative of how it would help the left and not the right blocks passage of these common-sense voter laws.

The truth is that in Alaska, registered Republicans, Democrats, and especially independent voters could all stand to gain from pro-voter laws like same-day registration and a cure process for mailed ballots. Similarly, at the federal level, more reliable mail service would help all voters across the political spectrum (and not just during elections).

For the third year in a row, lawmakers in Juneau have the legislation before them to make it happen.

Alaska has a history of middling voter turnout

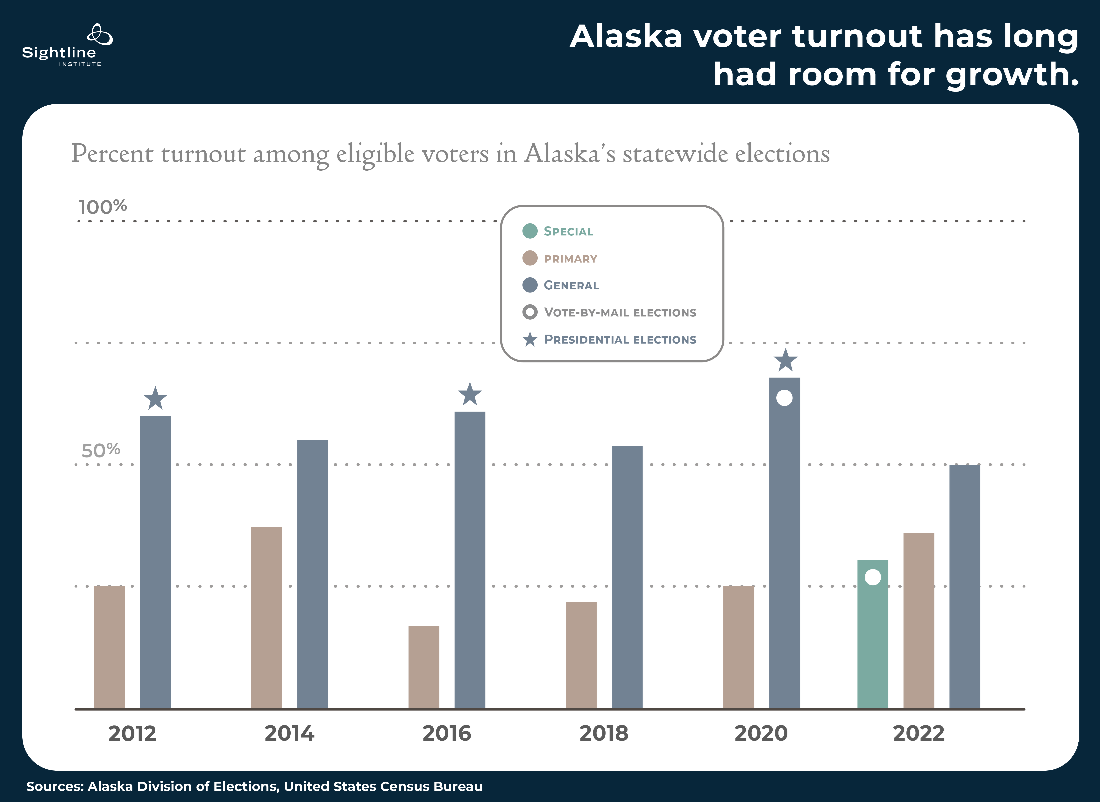

In Alaska’s most recent six elections, statewide voter turnout1 ranged from a low of 17 percent in the 2016 primary election to a peak of 68 percent in the 2020 general election. If voter participation statewide were graded using the Anchorage School District system, the report card would say “N” for “Needs Improvement.”

Several factors contribute to patterns in turnout and can be observed in the chart below:

Public awareness of high-profile campaigns: High-profile contests, particularly the US presidency (starred on the chart below), motivate voters to go the polls, causing peaks during presidential election years and troughs at the midterms.

General versus primary elections: More voters show up for general elections (blue bars in the chart below), when their votes will lead directly to a decision about who is elected, as opposed to primary elections (light brown bars in the chart below), which narrow the candidate field but don’t produce a winner.2

Lead time for voters and officials: Special elections often have the lowest turnout because the date isn’t set until a few weeks before the election. Election officials have less time to publicize information about the election, and voters have less time to plan when, where, and how they’ll vote. Alaska had one special election in 2022 to choose a replacement for U.S. Rep. Don Young, who died in office after representing Alaska in Congress for 49 years. The special primary (green bar) occurred in June 2022. The special general election was on the same ballot as the regular primary election in 2022.

Voter profile: More experienced voters tend to pay more attention to the timing of elections and are more likely to vote. For that reason, special election voters tend to be more politically active and older than the average registered voter in the same district.3

Aside from the factors listed above, turnout in individual elections can vary significantly for other reasons. On one hand, turnout could go up if the election were conducted fully by mail (indicated by white dots on the chart above), improving convenience for voters, or if a candidate or contest received a lot of media coverage and inspired more voters to come out. On the other hand, turnout could go down if the only statewide office on the ballot one year had a popular incumbent running uncontested, so voters didn’t feel the need to show up, or if candidates discouraged voters from participating.

Case study: The 2022 midterm election

Consider 2022, a midterm year when the absence of a high-profile presidential contest means fewer voters typically participate. That year, Alaska posted strong turnout for the primary and slightly lower than usual turnout for the general election. Attributing turnout numbers to any one factor would be a huge mistake, but listing the factors that might have played a role is kind of fun.

In 2022, Alaska’s electoral landscape underwent dramatic changes on many fronts. The big news was the death of Rep. Don Young in March. State election officials had to scramble to hold a special primary election in June and then combined the special general election with the regular primary on a single ballot in August. The state also debuted its system of open primaries and ranked choice general elections.

Perhaps most importantly, Alaska election officials toggled between all-mail/absentee and in-person elections. In 2020, as the COVID-19 pandemic spread, Alaska moved to all-absentee elections and saw record high turnout. It revived the all-absentee approach in June 2022 for the special primary, posting turnout that exceeded most of the previous regular primary elections.

But during the subsequent regular primary/special general election ballot in August and the regular general election ballot in November, the state reverted to its previous practice of requiring voters to request mailed absentee ballots. While turnout for the regular primary was strong, the general election numbers were down. It is possible that voters who automatically received a ballot in the mail for the 2020 general election were expecting more of the same in 2022. When they didn’t receive a ballot, they didn’t vote. (Please keep this in mind. We’ll return to the importance of consistent all-mail voting later in this article.)

In short, for a variety of reasons, middling voter turnout has persisted among Alaskans through six elections across more than a decade. And, as we discuss in the next section, Republicans, Democrats, and Independents in Alaska cast ballots at roughly the same unimpressive rates through both midterm and presidential elections. Turnout, it turns out, is everyone’s problem.

Alaska’s voter turnout is unimpressive for Republicans, Democrats, and everyone in between

“Because there are nearly twice as many registered Republicans as registered Democrats in Alaska, similar percent turnout among those groups means nearly twice as many Republicans failed to vote as Democrats.”

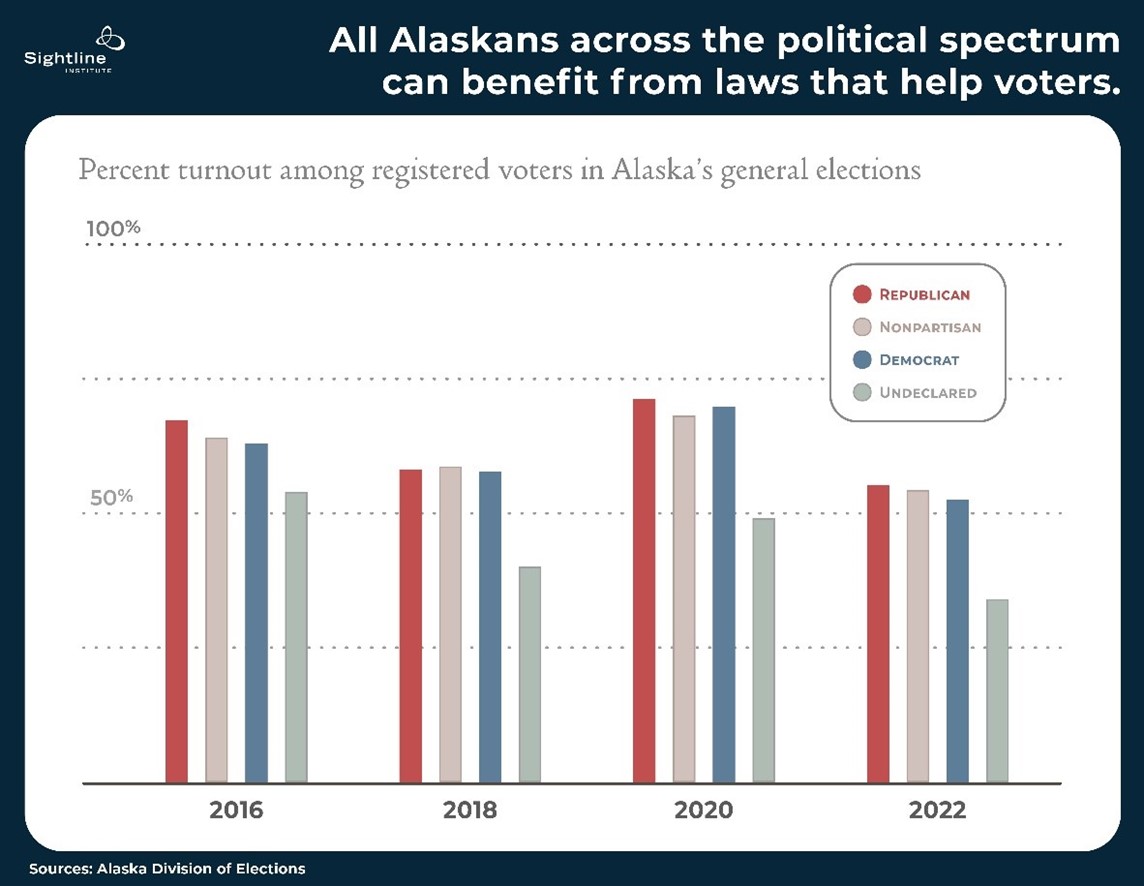

The chart below shows voter turnout by party for the last four general election cycles. We looked at the total number of registered voters in each party (and non-party) and figured out what percentage of them voted in each of the last four November elections. Since turnout is consistently lower during midterms than in presidential years, we chose two of each to provide apples-to-apples comparisons.

Only a slightly higher share of registered Republican voters came out each cycle compared to Nonpartisans and Democrats, regardless of whether it was a midterm or presidential year. In every election, tens of thousands of registered Republicans, nonpartisan voters, and Democrats didn’t cast a ballot. And because there are nearly twice as many registered Republicans as registered Democrats in Alaska, similar percent turnout among those groups means nearly twice as many Republicans failed to vote as Democrats.

Looking at voter turnout by geography, the lowest-turnout state legislative districts include those near military bases in Anchorage and Fairbanks and in remote villages along the Arctic and Bering Sea coasts. That’s not surprising. The military is highly transient and skews young, so in addition to being new to Alaska, transplants in the armed services could very well be new to voting. And in rural communities, poor weather, unreliable transportation, and postal service vacancies can stymie even the most committed voters.

Thanks to Brian Walker for supporting a sustainable Cascadia.

Our work is made possible by the generosity of people like you.

With turnout percentages tracking about the same for all major groups of voters, lawmakers across the partisan spectrum should be rallying to address these issues and make voting easier for all their voters.

What Alaska lawmakers can do to increase voter turnout

Make it convenient, like Montana

As we’ve seen, lawmakers can’t control every variable that affects turnout. But a key factor they can influence is convenience. Convenience greatly affects the likelihood a person will vote. Sure, a person’s decision to fulfill their civic duty is ultimately their choice. But just like sitting on hold for an hour makes it more likely that you’ll give up on protesting that denied insurance claim, deterrents to voting diminish the odds you’ll get your ballot in. If the laws governing election logistics make voting feel like great customer service, more people will do it. But if it feels like an insidious IQ test or an unwinnable game, constituents won’t bother.

Take Montana, a state whose hybrid voting system supports both in-person and absentee voting. Montana already has in place some key pro-voter policies that Alaska has yet to enact. For instance, Montana allows voters to register on Election Day. It also makes absentee voting extremely easy by allowing permanent absentee registration for all voters, providing ballot tracking, using voter signatures as a verifier rather than Alaska’s practice of requiring unchecked witness signatures, and, like about two-thirds of US states, has a cure process for mailed ballots. It’s no surprise that Montana’s general election turnout is consistently high relative to other US states and has been higher than Alaska’s in all but one general election since 2012.

Alaska’s Republican legislators tend to drag their feet on pro-voter laws. So it may be worth nothing that Montana is a very Republican state that reliably sends its electoral votes to Republican presidential candidates and whose state legislature is dominated by Republicans. Three of the four members of Montana’s Congressional delegation are Republicans. So is its governor.

And lawmakers on both sides may find comfort in a study by the University of Virginia’s Center for Politics that found absentee voting doesn’t give one party an advantage over the other. “All told,” the study authors wrote, “The sharp increase in absentee voting in 2020 wasn’t disproportionately beneficial to either presidential candidate.”

Strengthen the postal service

In addition to passing Montana-style pro-voter laws at the state level, Alaska lawmakers at all levels of government should be advocating for the US Postal Service to boost recruitment efforts for postmasters, who manage employees and oversee the delivery of ingoing and outgoing mail. The post office plays a critical role in delivering ballots from polling places to vote counting centers on time and ensuring timely postmarking of absentee ballots sent on or before Election Day. A study published in 2023 in the Election Law Journal found that convenient absentee voting laws boost voter turnout, but that even in states with restrictive absentee voting laws, good postal administration alone helped increase voter participation.

The issue of functioning post offices is particularly acute in rural Alaska. Nearly 80 rural communities across all regions of the state don’t have a postmaster, according to a recent count by the US Postal Service. In 2022, the US Postal Service failed to deliver ballots from six rural Alaska communities to the state’s election headquarters in time to be counted in the general election results. Though the number of ballots involved wasn’t large enough to affect the outcome, the late delivery resulted in the disenfranchisement of 259 voters.

No need to reinvent the wheel on key pro-voter laws

In 2022, Sen. Mike Shower, R-Wasilla, and former Rep. Jonathan Kreiss-Tompkins, D-Sitka, along with other members of both parties, collaborated on an excellent multipartisan election bill that would have made absentee voting easier and cleaned up Alaska’s bloated voter rolls. The legislature gaveled out before the bill could be passed. In 2023, the Alaska House and Senate took another run at improving the voter experience, but once again fell short.

Still, those bills included a slew of sensible proposals that leaders could take up again to support Alaskans of all political stripes and ensure their constituents’ voices are heard:

Give voters a cure process: Allow voters to correct mistakes on their absentee ballot envelopes so their vote counts rather than gets tossed out.

Drop the witness requirement: Ditch the requirement for voters to have a witness sign their ballot. The state doesn’t even verify the authenticity of witness signatures but still tosses out ballots that lack them.

Set up “one and done” absentee voter sign-up: Require a one-time sign-up to receive absentee ballots for all statewide elections, rather than repeated sign-ups year after year. Alternatively, allow voters a one-time sign-up good for a period of four years. While not as efficient as permanent absentee ballot registration, it would improve upon the current policy requiring voters to re-register for absentee ballots every year.

Same-day voter registration: For presidential and vice-presidential elections, Alaska already allows voters to register to vote on the same day they cast their ballot. The state should expand same-day voter registration to all contests to accommodate people who have moved between districts, are new to the state, or who did not apply for a permanent fund dividend and therefore were not automatically registered.

Count absentee ballots sooner: Allow the Division of Elections to start processing (or even counting) absentee ballots no fewer than seven days prior to Election Day.

Provide postage-prepaid return envelopes: Spare voters the search for a postage stamp—especially those without a secure ballot drop box nearby. They could drop the provided prepaid return envelope straight in the local mail. Alternatively, the US Postal Service could continue delivering all absentee ballots, regardless of whether they have postage, and improve outreach to let people know their ballots will be sent even without postage.

Establish a tracking system for absentee ballots: Allow absentee voters and election officials to track their ballots with intelligent mail barcodes. Get live updates when the Division of Election mails it out, when the voter receives it, when the Division receives it back, whether they find any problems with it, and when they’ve counted it—not unlike tracking an online order.

Audit the master vote list: Alaska is already one of 31 states belonging to the Electronic Registration Information Center (ERIC), a program for keeping voter lists clean and accurate. Using ERIC, states can remove from their rolls voters who have passed away, moved, or registered to vote in another state. They can also update the addresses of those who move within Alaska. But even after using ERIC’s data to remove these voters from the rolls, Alaska still has more registered voters than voting-age residents. Alaska can ensure it’s using the best available information sources for keeping voter lists updated with biennial third-party audits of the master voter list.

Helping Alaskans get beyond so-so turnout

Aside from the 2020 general election, when Alaska ran a universal vote-by-mail election and a nail-biter of a presidential contest brought voters out in droves, turnout in Alaska has hovered right around 50 to 60 percent. Though middling voter turnout occurs regularly, it doesn’t have to be the norm. Lawmakers on both sides have a strong case for supporting upgrades to the state’s voting system rather than engaging in another run-of-the-mill partisan fight.

Our analysis shows ample room for improvement in turnout for Alaskans across all major political groups. And while we didn’t actually break it down, it’s safe to assume the beneficiaries of more voter-friendly policy would include all sorts of Alaskans: military personnel and civilians, urban and rural residents, newbie and seasoned voters, subsistence users and supermarket shoppers, skiers and snowmachiners.

Obviously, these groups overlap, and that’s really the point. Every eligible voter in Alaska, not just certain demographic groups or members of one political party, would benefit from a smoother voting experience. And state lawmakers are the people with the power to provide it.