Takeaways

Dozens of major polluters, from oil refineries to pulp and paper mills to electronics manufacturers, dirty Cascadia’s air and add to the region’s climate-warming pollution every day, even in places with strong climate policies.

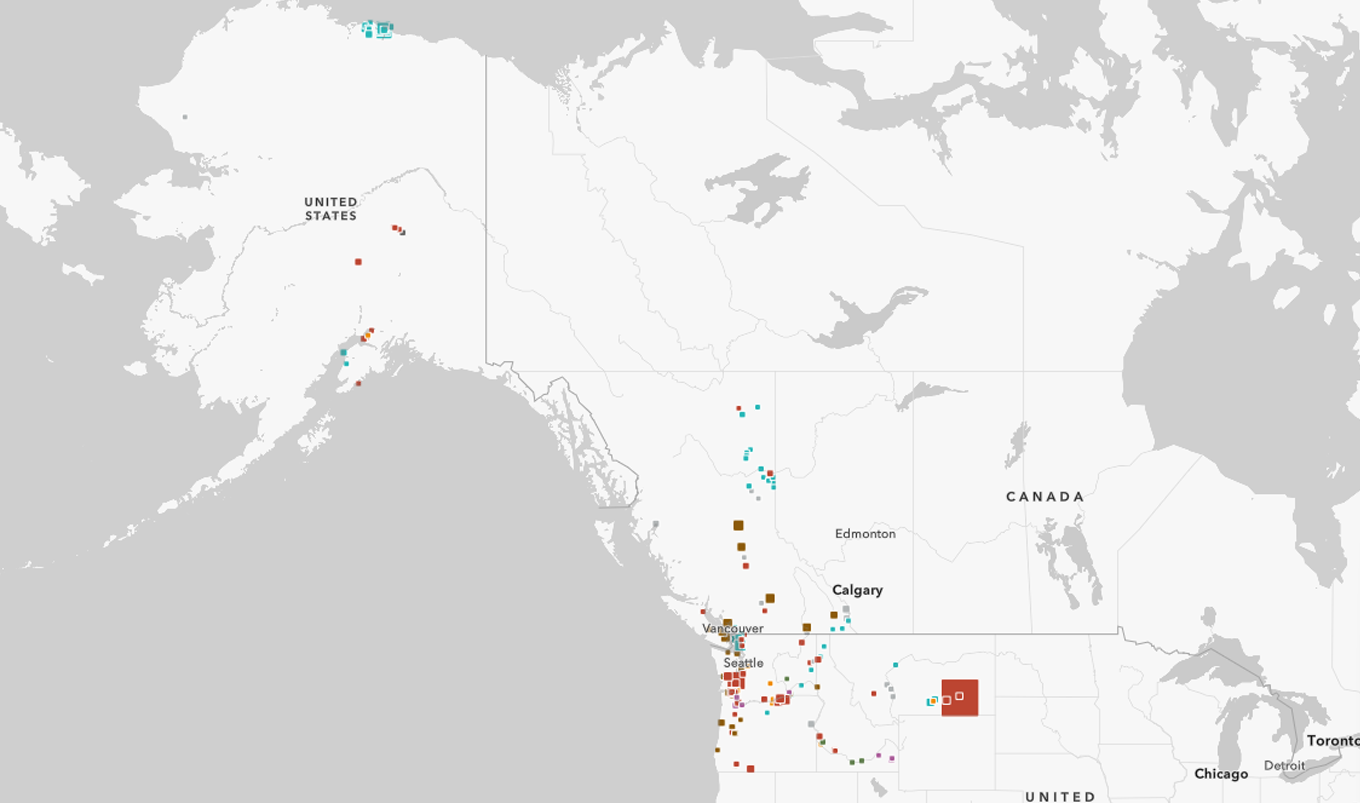

Alaska, British Columbia, Idaho, Montana, Oregon, and Washington count 180 stationary facilities that each emit more than 100,000 metric tons of carbon annually, accounting for roughly a quarter of the entire region’s carbon pollution.

Despite their hefty carbon footprints, these big polluters enjoy notable loopholes in the region’s climate policies, whether because of their economic importance or their difficulty to clean up.

Still, unless policymakers fill in the cracks and reckon with these industries’ pollution, these facilities could keep fouling the region for longer than our climate can afford.

Find audio versions of Sightline articles on any of your favorite podcast platforms, including Spotify, Google, and Apple.

Cascadia chalked up major climate wins in 2023, from Washington’s renewed commitment to eliminating gas appliances in new buildings to Montana youth’s historic court win for a clean and healthy climate. At the same time, many Northwest climate hawks are gearing up for new challenges in 2024, including a likely bitter fight to defend Washington’s landmark climate law, the Climate Commitment Act, from a rightwing repeal effort.

Still, as policy debates rage, it can be easy to forget that every day, scores of huge polluters continue to dirty Cascadia’s air, making the worst effects of climate change ever more difficult to stave off.

Cascadia counts 180 stationary facilities that each spew more than 100,000 metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e) into the atmosphere every year.1 (For the purposes of this article, Cascadia refers to Alaska, British Columbia, Idaho, Montana, Oregon, and Washington. The analysis covers the entirety of the states and province for data simplicity, not only the Cascadian bioregion.)

The biggest emitters range from coal-fired power plants to sugar processing plants, from electronics manufacturers to pulp and paper mills, from landfills to oil refineries to zinc mines. Across the region, power plants, oil and gas facilities, and the forest products industry top the list of biggest stationary polluters, as shown by the charts below, the first broken by down state and industry, the second simply by industry, and the following broken out for each state or province.

Collectively, these establishments emit roughly 80 million metric tons of carbon pollution annually from fossil fuels, about a quarter of Cascadia’s total greenhouse gas emissions.2 These facilities’ emissions rise to more than 103 million metric tons of carbon pollution annually—more than comes from driving 23 million gasoline-powered cars in a year—when biogenic emissions are included.3278 million registered vehicles.) Nearly half that carbon comes from just 20 facilities in Cascadia, indicated by the boxes at right in the chart below.

Cleaning up these institutions is no simple task. Few can easily decarbonize with current technology. Some employ hundreds or even thousands of people.

Still, policymakers can’t afford to ignore them in their efforts to address climate change and improve air quality. That’s especially important in British Columbia, Oregon, and Washington, which many consider to be the greenest jurisdictions in Cascadia yet are home to 120 of the region’s 180 top polluters. While all three state or provincial governments have passed policies to reduce emissions from big stationary sources, notable loopholes remain.

The first step, though, is understanding who the top polluters are and what exceptions to climate laws they enjoy today. With that in mind, Sightline offers four takeaways for Cascadian policymakers.

1. Coal may not power Oregon or Washington for long, but it could dirty Cascadia for decades

Far and away Cascadia’s biggest polluter is the gargantuan coal-fired power plant in Colstrip, Montana. Emitting more than 10 million metric tons of carbon annually, it spews nearly three times as much CO2e as the next biggest polluter on the list. In fact, it releases so much carbon from burning coal to make electricity that it carries the dubious distinction of being one of the top emitters in the entire United States.

Source: Map by Sightline Institute. View a full, interactive version of map.

Today, six utilities across the Northwest—Avista, NorthWestern Energy, PacifiCorp, Portland General Electric (PGE), Puget Sound Energy (PSE), and Talen Energy—co-own the plant. But Washington and Oregon passed laws requiring utilities in these states to remove coal from their portfolios by 2025 and 2030, respectively. PGE demolished Oregon’s last coal-fired plant near Boardman in 2022, and TransAlta will shutter Washington’s last coal-fired plant by 2025. As such, residents in western Cascadia could be forgiven for assuming that they no longer need to worry about coal-powered electricity or Colstrip.

Unfortunately, though, Colstrip looks like it will be fouling Cascadia for the foreseeable future, even after Oregon and Washington utilities pull out. Avista and PSE, the Washington utilities that own a portion of the plant, announced in March 2023 that they will transfer their ownership stakes to the Montana-based companies in 2025, rather than push for the facility’s retirement. A similar proposal in 2020 elicited concern from Washington legislators that it undermined the intent of the state’s clean electricity law. But Washington policymakers’ response to this latest plan has been muted. Meanwhile, Oregon utilities PGE and PacifiCorp announced earlier in 2023 that they will delay their exit from the plant by five years, from 2025 to 2030—the latest possible exit date that Oregon law allows.

Perhaps alarm that Colstrip will keep belching pollution for decades after Oregon and Washington utilities have stopped relying on it is unfounded. The economics of coal plants look increasingly shaky. In fact, two of Colstrip’s four units closed in 2019 because of economic unviability. And in May 2023, the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) proposed a new rule to reduce carbon pollution from coal plants by 90 percent by 2030. In practice, the cost of the technology to comply with this rule would likely lead many coal plants, including perhaps Colstrip, to shutter.

Still, EPA has not yet finalized that rule, and it is likely to face legal challenges. Montana’s leadership, meanwhile, has shown it isn’t giving up on coal without a fight.

Oregon and Washington lawmakers committed to phasing out coal in the region would be smart to renew pressure to close Colstrip, rather than simply wash their two states’ hands of it.

2. Even without coal, generating electricity is a dirty business in Oregon and Washington

Unlike most other US states, both Oregon and Washington rely primarily on electricity generated without burning fossil fuels, due largely to the abundance of hydroelectric dams in the Northwest.

Even so, fossil-fuel-fired power plants top the list of big stationary polluters in both states. The vast majority of these are powered by burning fracked gas; the notable exception is TransAlta’s coal-fired power plant in Centralia, Washington, which the company will shut down by 2025.4

Thankfully, Oregon and Washington recently passed clean electricity laws that should phase out fossil-fuel-fired power plants over the next 20 years, if not sooner. Washington’s 2019 Clean Energy Transformation Act (CETA) mandates that the state’s electricity supply be greenhouse-gas-neutral by 2030 and powered 100 percent by renewable energy by 2045. Oregon’s 2021 Clean Energy Targets law, better known as HB 2021, requires electric utilities to zero out emissions by 2040, with interim targets between now and then.

Still, exceptions baked into both states’ laws could prolong these polluters’ lifespans beyond what lawmakers intended. Washington’s CETA considers utilities compliant with the law if their efforts to meet emissions reductions targets exceed a two percent annual average increase in costs to utility customers.5 In other words, if it’s too expensive to leverage the wind and sun for power, Washington utilities can keep burning gas. Likewise, Oregon’s HB 2021 lets utilities miss emissions targets if generation from renewables is lower than expected or electricity demand is higher than anticipated.6

One factor that could lead utilities to rely on these exceptions and keep gas-fired power plants spewing far longer than the region can afford? Not enough electric transmission capacity in the Northwest to be able to tap cheap and abundant renewable power. That’s in large part because most of the gas-fired power plants in both states—11 out of 17—are located west of the Cascade mountain range. By contrast, most of the best renewable sources are much farther away, whether wind in Montana and Wyoming or sun in eastern Oregon and Arizona. Utilities need big power lines to transport this energy to western Oregon and Washington, as Sightline has written.

Policymakers in the Evergreen and Beaver states have several tools at their disposal to increase the region’s electric transmission capacity and can at the same time remain vigilant in making sure utilities don’t abuse clean electricity law exemptions.

3. Oil and gas facilities dominate the list, even in Cascadia’s greenest places

As one of the United States’ top five oil-extracting states and the state with the fourth-largest gas withdrawals, Alaska unsurprisingly counts mostly oil and gas facilities in its list of big polluters. The majority are located in the Prudhoe Bay region on the North Slope, an area that contains six of the largest oil fields in the United States and one of country’s the largest gas fields. ConocoPhillips’ giant new oil drilling project, the Willow Project, will add another enormous fossil fuel polluter to Alaska’s North Slope. President Biden approved the project in March 2023, to the dismay of many of his supporters.

But the story of oil and gas in Cascadia doesn’t end in Alaska. Washington is the fifth-largest US oil-refining state, and its oil refineries dominate the state’s list of top polluters. Indeed, once the TransAlta coal-fired power plant shutters in 2025, the BP, HF Sinclair, and Marathon oil refineries will dirty Washington’s air more than any other stationary sources. The chart below shows the emissions of Washington’s top polluting stationary facilities, by industry.

Until 2023, Washington had not started to map out a potential future for the refineries the state hosts, despite Governor Inslee’s commitment to ramp up the transition to electric vehicles and thereby slash demand for oil. But, thanks in part to Sightline’s efforts to shed light on the risks to workers and the environment of an unplanned transition off of oil, the 2023 state legislature allocated a quarter-million dollars to start charting a smooth course for Washington’s refineries.

Still, Washington has yet to fully reckon with ongoing colossal pollution from the oil sector. While the state’s landmark climate law, the Climate Commitment Act (CCA), includes the refineries under its declining state-wide emissions cap, it allows the facilities to receive free allowances to continue polluting at, or close to, their current levels for at least the next decade. Under the CCA, refineries can continue polluting for free at 100 percent of current emission levels until 2026; this figure drops to 94 percent of baseline emissions by 2034. The state has not yet established an emissions cap or allowance policy for oil refineries after 2035. The CCA’s carveouts for oil refineries and other large industrial facilities are part of why environmental justice group Front and Centered has criticized components of the law.

In the short term, Washington policymakers could at least consider technical solutions to reducing oil refinery emissions; the think tank RMI offers several ideas, including cutting methane leaks and shutting down some especially dirty units. Still, soon the state will need to develop a post-2035 emissions reduction plan for these facilities to allow the CCA to meet its promise.

Farther north, in what’s often considered Canada’s greenest province, fossil fuel facilities also dominate the list of top polluters. In British Columbia, though, fracked gas, not oil, is the name of the game. British Columbia accounts for 35 percent of Canada’s gas output; Canada, in turn, is the sixth-largest gas extractor in the world. Many of the province’s dirtiest facilities are found in northeast British Columbia where companies like Shell and TC Energy frack gas from what’s known as the Montney Formation. Fracking in the Montney Formation drove the province’s gas output to double since 2010. This fracked gas snakes its way through pipelines across the rest of Cascadia where homes and businesses burn it in furnaces, stoves, industrial processes, and more. Idaho, Oregon, and Washington, which have no gas reserves themselves, rely especially heavily on Canadian fracked gas.

Like Washington, British Columbia has yet to fully reconcile its climate commitments with its dependence on the fossil fuel industry. In 2022, the BC government revised its oil and gas royalty system to remove some fossil fuel subsidies, but critics say the new regime still incentivizes fracking.

Meanwhile, the UN announced in November 2023 that Canada has the most yawning gap between climate commitments and concrete climate policies to achieve those commitments of any country in the world. That same month, Canada’s Auditor General warned that the country is unlikely to meet its 2030 emissions target. A step in the right direction would be a cap on emissions from the oil and gas sector, which Prime Minister Trudeau promised in 2021 that his administration would establish. As of December 2023, there is still no cap in place.

4. Forest products facilities are top polluters, but Cascadian emissions limits give them a free pass

The roots of the forest products industry run deep in western Cascadia. British Columbia exports more wood products than most other areas of the world, and Oregon and Washington top the United States’ list of lumber producers.

Thanks to Richard Marshall for supporting a sustainable Cascadia.

Our work is made possible by the generosity of people like you.

At the same time, forest products facilities, such as pulp and paper mills and lumber mills, are some of the region’s biggest stationary carbon polluters—only most Cascadian climate policies give them a free pass.

The reason stems from a distinction many make between biogenic emissions—carbon released from burning or decaying organic matter like wood—and fossil fuel emissions released from burning coal, oil, or gas. The vast majority of the carbon emissions from forest industry facilities are biogenic emissions. For example, pulp and paper mills release biogenic emissions when burning biomass or wood fuels as part of their industrial processes. The chart below shows the emissions from forest industry facilities in British Columbia, Oregon, and Washington, broken out by biogenic and non-biogenic sources.

(The forest products emissions discussed in this section are only those from stationary facilities like pulp and paper mills, not the broader net release of carbon from forests via wildfires, clearcuts, etc.)

Including biogenic emissions in carbon calculations catapults forest industry facilities to the top of the big stationary polluters lists in British Columbia, Oregon, and Washington. In British Columbia, pollution from pulp and paper mills and lumber mills is more than triple that of oil and gas facilities when accounting for biogenic emissions.

But not everyone counts biogenic emissions. Some argue that new growing forests or other plants will reabsorb the carbon that burning wood products releases into the atmosphere. Others argue that because the timeframe within which a tree initially absorbed carbon and then later releases it when burned is relatively short (hundreds of years), burning wood in forest products facilities doesn’t lead to a long-term change in atmospheric carbon levels. By contrast, fossil fuels took millions of years to form, so burning them does change long-term carbon levels.

As such, while British Columbia, Oregon, and Washington all require big stationary polluters like pulp and paper mills to report their biogenic emissions, none of these jurisdictions includes this type of pollution in state- or province-wide greenhouse gas inventories or carbon emissions limits. Washington’s CCA, for example, exempts “carbon dioxide emissions from the combustion of biomass or biofuels.”

But the rationales for ignoring biogenic emissions in economy-wide greenhouse gas emissions look specious upon closer examination. The world needs to slash carbon emissions today to have a fighting chance of mitigating the worst effects of warming. Assurance that carbon that comes from burning wood products in an industrial facility will be reabsorbed later by some future hypothetical forest or other plant—or that that the carbon was recently already in our atmosphere, so putting it back doesn’t make a difference—is cold comfort in this context.

At a minimum, policymakers in British Columbia, Oregon, and Washington can shed light on the region’s biogenic emissions by requiring that agencies include these sources of carbon in state- or province-wide greenhouse gas inventories. They can also explore technical solutions for reducing emissions from the forest products industry, such as the recommendations for reducing emissions from the pulp and paper and wood products sectors developed by the Clean Energy Transition Institute and the Stockholm Environment Institute in 2021. No matter what, Cascadian leaders can’t afford to ignore the pollution from these longstanding industries any longer.

Cleaning up big polluters: Hard but necessary

Major polluters, from oil refineries to pulp and paper manufacturers, sully the air across Cascadia, even in its greenest corners. The 180 dirtiest facilities in the region are also the hardest to clean up, whether because of their importance to the local economy or the technical challenges in doing so. Unsurprisingly, then, loopholes abound for these big emitters, even in Cascadia’s best climate policies. But Cascadian policymakers can’t afford to ignore them any longer. They can immediately start filling in cracks in current policies and exploring short-term technical fixes to clean up some pollution while they reckon with the longer-term role of these industries in Cascadia. No matter what, the clock is ticking.

Appendix: Data and methodology

Sightline relied on the most recent available data for large stationary emitting facilities as of December 2023 to identify all facilities emitting more than 100,000 metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e) in Alaska, British Columbia, Idaho, Montana, Oregon, and Washington. The emissions included in this analysis are direct emissions from the facilities only, not emissions associated with end use of a product. For example, the tailpipe emissions from a car burning gasoline refined at a Washington oil refinery are not included. Sightline excluded any facilities known to have closed since the data was released.

The data source for British Columbia is the BC Ministry of Environment and Climate Change Strategy’s 2021 Large Industrial Facilities. Sightline removed one large emitter from the BC list (the PowerEx EIO facility) due to incomplete data. The BC Ministry of Environment and Climate Change Strategy did not provide Sightline with the missing data for this facility when requested.

The principal data source for all Cascadian US states is the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) 2022 Greenhouse Gas Reporting Tool. This data may differ slightly from state-level facility emissions data reported by Washington’s Department of Ecology and Oregon’s Department of Environmental Quality. However, as of this writing, both Washington and Oregon have only released facility emissions data through 2021. Additionally, Alaska, Montana, and Idaho do not collect or report state-level data on facility emissions. Thus, for consistency and to rely on the most up-to-date data, Sightline relied on EPA data for all states.

The exception to using EPA data for US states is for facilities in Oregon or Washington that emit more than 100,000 metric tons of carbon when biogenic emissions are included but emit less than 25,000 metric tons of fossil fuel emissions. These facilities do not appear on EPA’s list, which is limited to facilities that emit more than 25,000 metric tons of carbon from fossil fuels. Thus, Sightline reviewed Oregon and Washington’s 2021 state-level data and added any facilities that, when biogenic emissions are included, release more than 100,000 metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent. If these facilities were not on the EPA list, Sightline relied on 2021 state-level data for both non-biogenic (fossil fuel) emissions and biogenic emissions.

Comments are closed.