Anchorage is exceptional. You can be neighbors with moose and see the aurora from your deck. But on housing policy, Anchorage conforms to the Anytown, USA model of zoning rules that stock neighborhoods with a generic product: suburban one-unit homes. The intentions behind the code weren’t necessarily nefarious, but the effects certainly are. Anchorage zoning code limits market choice, contributing to a shortage of homes across the price spectrum, and weakens Alaskans’ spending power by flooding the state’s economic hub with the priciest of housing types.

The severity of Anchorage’s housing shortage has brought Anchorage’s conservative mayor and majority-progressive Assembly into agreement on reforms to help expand housing choice. In the past year, they have made accessory dwelling units easier to build, repealed parking mandates, which can block housing and business development, and introduced a potentially game-changing rezoning ordinance that put a spotlight on the concept of middle housing. In a unanimous vote in April, the Assembly updated downtown zoning code to encourage more housing development on the acres of parking lots and other underused properties in the city center.

The downtown reforms were a necessary step toward unlocking millions of square feet for housing and the businesses that support car-optional downtown neighborhoods. Adding more units downtown could help stabilize prices city-wide, provide more apartment-style living options, and achieve the city’s longtime goal of keeping downtown’s vibrant summer economy alive year-round. Downtown businesses need customers after the tourists leave in the fall. With remote work likely here to stay, Anchorage’s office workers aren’t enough. The only way to create a permanent pool of customers is to turn downtown into a place for locals to live.

Scant housing in Anchorage’s “most desirable neighborhood”

Most Anchorage residents live in suburban neighborhoods that look like countless others across America. But many would happily move to a more urban setting if the market produced the type of housing they truly preferred. Household sizes have shrunk in the last two decades, both in Anchorage and nationwide, and cross-generational competition for more compact housing is fierce. A downtown flat can fit the lifestyles and budgets of these smaller households—empty nesters, retirees, young professionals, and single parents—better than an overlarge single-unit home. In a 2018 Anchorage Economic Development Corporation housing survey, nearly one-third of 1,110 respondents ranked downtown as one of their top three neighborhoods. The city’s Downtown District Plan calls it “the most desirable neighborhood in Anchorage.”

There’s a huge disconnect between demand and supply. Between 2000 and 2020, the share of one- and two-person households in Anchorage grew. At the same time, the share of households with three or more people shrank. And yet, Anchorage’s housing market prioritizes the one-unit-per-lot model—the largest, most expensive housing type. In 2000, 46 percent of occupied homes were single detached houses. Twenty years later, the market share of these houses had swelled to 58 percent. Adding more housing units downtown can help correct the imbalance in the market.

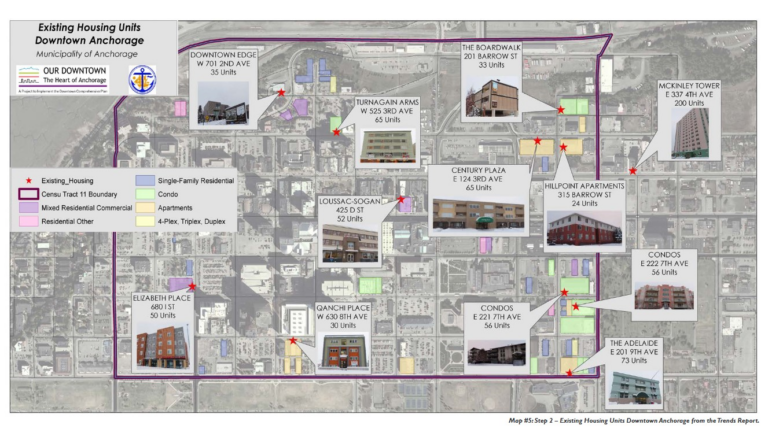

Existing housing units in downtown Anchorage (Image Credit: Municipality of Anchorage, Anchorage Downtown District Plan 2021)

Only 614 units exist in the downtown core, according to municipal data. In producing its 2021 Downtown District Plan, the city began exploring ways to add another 1,400 housing units and envision what they might look like. But the architecture firm contracted to produce renderings depicting the Plan’s vision for new housing downtown came back with bad news. The city’s own zoning code, written years earlier, discouraged attractive, modern residential developments.

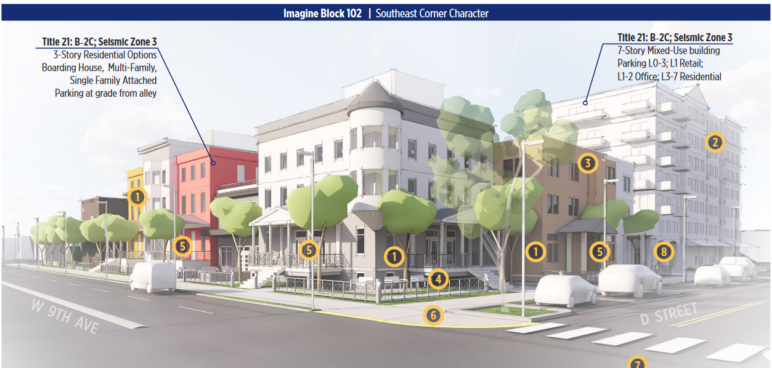

“They hired us to do the renderings, and we found we couldn’t accurately portray the vision in a way that was true to what was possible according to Title 21 code because a lot of these newer residential building types the plan called for downtown were not allowed,” said Mélisa Babb, a landscape architect who managed the project for architecture and design firm Bettisworth North. “We kept having to come back and say, ‘Well, you can’t build that nice new tower because we can’t do residential like that downtown.’”

This block of homes would have been illegal before the Anchorage Assembly unanimously passed downtown zoning code revisions in April 2023.

This realization gave rise to reforms for the three zoning districts that make up downtown, roughly bordered by K Street, 9th Avenue, Gambell Street, and the Ship Creek industrial area. Among the changes:

- Expands the list of businesses and institutions allowed to operate downtown

- Bans new surface parking lots

- Adds flexibility to design constraints or gets rid of them entirely

Changes to land use rules alone won’t lead to abundant housing downtown, but they are a low-cost way for the city to remove obvious regulatory barriers. These and other zoning reforms are part of a larger suite of support for downtown housing that could include financing and tax incentives, as well as public spending on sidewalks, lighting, and safe options for non-motorized and public transit.

Bans on convenience stores and other businesses lifted

Walkable neighborhoods have huge appeal for people who envision themselves living downtown. Across the country, neighborhoods with high walk scores command premium prices because demand for walkable neighborhoods exceeds supply. They require, among other features, the close proximity of housing with key businesses and services. But in Anchorage, downtown caters primarily to visitors and office workers. Without a critical mass of residents, the businesses essential to everyday life are rare to nonexistent. Eateries, bars, and retailers abound, but some shut down or shorten their hours when customer traffic dwindles outside tourist season. Downtown Anchorage has two convention centers and plenty of coffee shops but no grocery store. It has a half-dozen cannabis retailers but no pharmacy.

Downtown Anchorage has two convention centers and plenty of coffee shops but no grocery store. It has a half dozen cannabis retailers but no pharmacy.

The recent round of code reforms lifted prohibitions on businesses that would support residential life downtown, such as convenience stores, veterinary clinics, and community centers. Other newly allowed institutions include an aquarium, school and university facilities, and pet boarding. The reforms also eased restrictions on small libraries.

“All these things were not allowed,” Babb said. “It’s invisible. You’re not going to see the difference until people open new businesses.”

The code changes alone won’t be enough to actually bring these new businesses downtown, but they do remove a major barrier. For example, the University of Alaska Anchorage now has the option to move offices or entire academic programs to city center, just as other universities have elsewhere. Adding student housing downtown would drive growth for existing businesses and perhaps attract others.

Convenience store owners should have an easier time now that their businesses are no longer prohibited. Proprietors have long used a loophole that classified them as restaurants as long as they sold food prepared on-site (which explains why you can get a chowder to-go and lip balm at that place on 4th Avenue). The reforms give them the option to jettison their commercial-grade kitchens and focus on selling snacks, band-aids, and beverages.

A much more diverse ecosystem of retail, services, and eateries would bring about more consumer choice, support neighborhood cohesion, and lay the groundwork for residents to leave their cars at home. Crucially, the city would need to work with the state to make downtown, including 5th and 6th Avenues, more bike and walker-friendly, while still accommodating motor vehicles. These and other changes can make downtown Anchorage living accessible to more people who don’t own a personal vehicle, want to minimize time spent in a car, or can’t drive for medical reasons. Pro-driving die-hards should likewise support safe alternative transit, like the city’s protected bike lane pilot projects. Fewer drivers mean less traffic and more available parking spots for them.

As a recent Brookings Institution report noted, “Ironically, an American economy that prides itself on consumer choice offers less transportation choice than our global peers.” By allowing more types of businesses downtown, Anchorage has moved an increment closer to transit diversity.

Surface parking lots banned

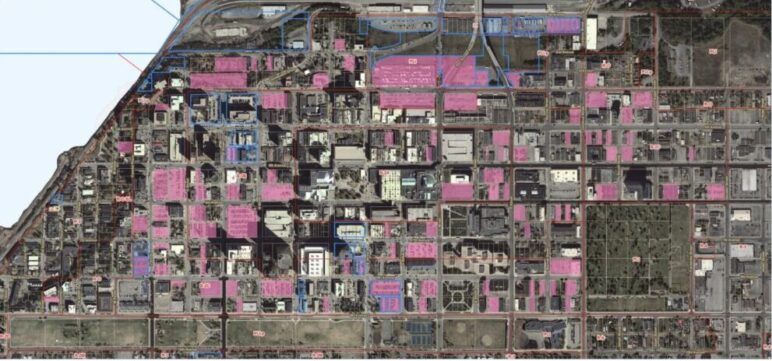

Surface parking lots encase huge swaths of downtown, turning some of the most valuable property in Anchorage into urban dead zones. Instead of millions of square feet of housing, boutique hotels, or cool restaurants generating the property taxes Anchorage relies on to function, the city center hosts acres of asphalt deserts. To slow the creep of this wholly inefficient use of land, the Assembly banned all new surface lots. (New multilevel parking structures are still allowed since they use land more efficiently.)

The search for parking downtown can be a minor hassle, but not for lack of spots. It’s just that most drivers (myself included) want a cheap spot on the street. The truth is that excess parking riddles the city, especially downtown. A 2007 study by the Anchorage Community Development Authority found that at peak downtown drive times, 5,445 parking spaces went unused. Driving tends to rise and fall with economic activity. With the 2023 economy slower than it was in 2007, the number of empty spots is plausibly even larger now, according to an analysis in the 2021 Downtown District Plan.

The city calculated that the unused spaces represent about 1.5 million square feet of “at grade” development (meaning just one story)—and that doesn’t count the multiple stories that could have been built above those spaces. With property taxes as the municipality’s main revenue source, the underutilized space represents a loss in funding opportunities for additional services and public infrastructure investments. But it also represents future opportunities for growth and improvement.

Surface parking bans aren’t common, but Anchorage isn’t alone. Last year Cincinnati instituted a temporary ban on new surface parking lots downtown. Its city council votes this year on whether to extend the ban in the urban core.

Pink highlights showing buildable lots in downtown Anchorage. Most of the highlighted lots host surface parking. (Image Credit: Municipality of Anchorage, Anchorage Downtown District Plan 2021)

Surface lots are lucrative and relatively cheap to maintain, giving owners little incentive to sell at prices that would make an urban residential project pencil out. The rates that lot owners charge for parking essentially cover the minimal property taxes they pay, giving them a way to wait out the market while generating income on an otherwise vacant property.

Instead of millions of square feet of housing, boutique hotels, or cool restaurants generating the property taxes Anchorage relies on to function, the city center hosts acres of asphalt deserts

“A lot of the larger parking lots downtown are owned by out-of-state operators,” said Anchorage Assembly member Daniel Volland. “They can essentially sit on that land while everything else is improved around them. And the property value goes up over time, and they can sell it for a big reward.”

Volland said that moving the downtown core away from being a giant parking lot will require additional policy tools. For example, the city could establish a stormwater utility funded by fees on the impermeable surface of the land. A grass lot with natural drainage would incur lower fees than a parking lot whose runoff would enter city storm drains.

A split-rate property tax, where the tax on the land itself is more heavily weighted than the building, is another idea for incentivizing surface parking lot owners to improve their property. Volland floated the idea of a land value tax that also provided residential property owners some relief.

The city for decades didn’t force developers or landowners to provide a defined number of spots for vehicles downtown, though it did for the rest of the city, at least until last year. And yet the problem of excess parking is arguably worse downtown than in any other part of Anchorage. The zoning code’s so-called “bonus table” for downtown incentivized parking by allowing developers to add more square footage to buildings but only if they added more parking or other features. As part of the reforms, the Assembly got rid of the bonus table, too.

Anchorage Saturday Market by Amy Meredith used under CC BY-ND 2.0

Lowering the hidden dimensional barriers

The Assembly also modified the rules dictating the size, shape, and spacing of lots and buildings. Known as “dimensional standards,” these arcane columns of numbers in a typical zoning code determine a city’s beauty and livability (or ugliness and un-livability, depending on your viewpoint). Let’s say a developer wants to turn a giant parking lot into apartments with a convenience store and restaurant on the ground floor. Dimensional standards that require a setback, or buffer zone between the sidewalk and the edge of the building or between buildings, could add significant costs to the project.

The Assembly also modified dimensional standards downtown by

- Reducing front, rear, and side setbacks to zero and allowing buildings to cover 100 percent of a lot, giving neighborhoods like Ted Lasso’s in London a chance to take root in Anchorage; and

- Getting rid of rules that set minimums for lot sizes and lot widths in all three downtown zones, giving property owners the flexibility to pursue a wider range of building shapes and sizes, like Rue Wellington in Montreal.

Federal height limits related to Merrill Field, the nearby municipal airport, still apply, and range from about 260 feet on the east side of downtown, gradually increasing to 480 feet on the western edge. But apartment buildings reaching those heights are unlikely in the near future. The Assembly added de facto height restrictions in the form of building step-backs, where floors above a certain height must be set back a certain distance from the edge of the building. In the central business district, the step-back rule kicks in at 112 feet, or about 10 stories. Building step-backs add to construction costs and may discourage builders from exceeding the height at which the requirement applies. No complaints here, though. A 10-story apartment building in downtown would add a significant percentage of housing to the area. The iconic Haussmann apartment buildings of Paris max out at 66 feet and none exceed six stories.

A downtown that’s everything to everyone all at once

Alaska communities and other tourist destinations often reserve the best of themselves for visitors. By opening downtown to more residents, the city can share the neighborhood with locals while continuing to accommodate tourists and the rest of us in Anchorage who are by turns office workers, theater-goers, bar-hoppers, restaurant patrons, and recreationalists. But in creating a downtown for residents, the city shouldn’t lose sight of what makes it work for visitors. Tourists flock to destinations, like cruise ships and Disneyland, that offer a large chunk of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs within walking distance. Ideally, downtown would provide the same all-inclusive resort convenience for its residents, along with everything else people appreciate whether or not they’re wearing their tourist hats: safe, clean streets, low vehicle traffic, public art, beautiful outdoor places to people-watch and socialize, and a strong sense of exactly where they are.