This article is part of the series Legalizing Inexpensive Housing

Takeaways

The author’s time living on the housing margins has opened his eyes to new ways to live imperfectly but under his own control.

Housing policymakers could better address the needs of the unhoused by learning from what many of them do already, when allowed.

We should allow incremental, simple, adaptable, and mobile housing forms.

Find audio versions of Sightline articles on any of your favorite podcast platforms, including Spotify, Google, and Apple.

Governments rule and fund from the center, and markets typically build for the top down. How, then, do those on unserved fringes adapt and house themselves?

To find out, look around. As Cascadians scramble for solutions to our housing crises, we could all gain some new ideas by observing the innovations of those already on the edges.

For the last decade I have taken a deep interest in—and it has taken me into—researching and living on the housing periphery. I’ve lived in warehouses, across a wide archipelago of house-sits and couch-surfs, and on rural sojourns off grid. I’ve lived in backyards, houseless villages, parking spaces, and prototype structures and vehicles. Living on these ever-shifting social shorelines, I am increasingly convinced that if we are all to survive and thrive, we must let the edges teach us.

Living in more “makeshift” housing has taught me to make and shift my own ways of living. It’s about playing the cards in hand, deftly. Surprisingly often, I discover unexpected ways it sharpens my game: I’ve learned that sleeping under a cloth roof gives me soft illumination in the morning and an energetic wake-up. I’ve learned that hot water bottles aren’t merely more efficient than hot air; they’re also cozier.

Cascadian housing policy can sharpen its game, too. Drawn from my experiences and research, I’ll discuss here three related housing approaches for radical agility and affordability.

- Create evolvable housing, not temporary shelter: “New Starter Homes”

- Facilitate self-building: Let people define, design for, and build for their own needs

- Roll out the ultimate scalable infill: The “Wheeler House” vehicle dwelling

1) Create evolvable housing, not temporary shelter: “New Starter Homes”

In recent years, US governments have invested a lot of money and focus in “pods” (temporary, free-standing, typically pre-fab structures) for unhoused people. In many cases, I believe, a better response would be quickly available housing that can evolve into permanent housing.

A recurring priority in disaster and homelessness response is reconnecting people with a regular, sustainable life as soon as possible, minimizing limbo. That sense of living in suspension, including the use of temporary housing forms, can inhibit recovery and redevelopment. Ian Davis’s 1978 classic, Shelter After Disaster, argued this point, and it’s a key part of the “Housing First” homelessness response philosophy.

A “sustainable life,” however, is not the same as getting to a permanent situation, conventional housing, or restoring the former state of someone’s affairs. Placement into something termed “permanent” might not be someone’s goal, could prove a dead end, or could soon become unsuited to a person’s or family’s evolving needs.

Instead, to rebuild lives, people need to see they are on a sustainable path, one on which they can step forward and self-determine rather than dwell in stasis or feel themselves as just a service recipient. People also generally want options to stay in, design, build, adapt, expand, and control or own their own homes. By contrast, pods and leased motel rooms don’t offer long-term and self-determined paths, nor is it sustainable to “reintegrate” people into conventional housing they can’t see a path towards affording.

So, what exactly are pod shelter sites usually missing? A direct, self-determining path to sustainable housing. Pod structures are typically temporary and non-durable, and residents aren’t allowed to stay on. Even the site itself is usually only temporarily permitted and planned for its location, even as subsequent housing options are by no means assured. Sites are also typically run by organizations that don’t themselves provide long-term housing. Likewise, as recently reported by The Oregonian, other common approaches such as rent assistance and hotel or motel stays often come with looming deadlines but no visible path to stability.

Applying this idea of creating direct paths of adaptation rather than interim states, I propose the “portable affordable dwelling,” or PAD, as an alternative to the now-pervasive pod. Or we might adapt a phrase from the real estate industry and call it the “new starter home.”

In this model, multiple levels of government, advocacy, design, and local communities variously collaborate to develop fast but evolvable, creative housing approaches. These could include portable homes that eventually become cottages in a backyard or cottage cluster—“the food cart of housing,” as I put it to Portland City Council last spring. Relatedly, a site itself, or the micro-community it hosts, might evolve from an outdoor shelter site into cottage cluster housing, a resident-owned mobile home park, or even a Baugruppe-type, resident-run co-op building.

Developing housing in stages is common practice in the developing and more recently developed world, such as Chile’s “half-a-house” concept, which prioritizes a basic, high-quality structure that can be expanded later if the owner chooses. I saw a similar approach in action this year while living and working on the site of a Portland nonprofit, Cascadia Clusters, which develops alternative housing forms. “New sites offering outdoor alternative shelter in Portland should be allowed to evolve into sites that have more permanent structures,” its director told a local TV station earlier this year.[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]

2) Facilitate self-building: Let people define, design for, and build for their own needs

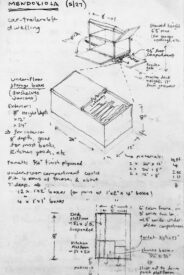

One of the key lessons policymakers can learn from alternatively housed neighbors is that people can and do build for ourselves, if allowed. For example, I recently built a lightweight, small cottage prototype for myself, in just a few days (shown under construction above), using “grid beam” DIY building methods. My beams are the same reusable, square, perforated steel tubing used for street signs all over Portland. The “Summer Pavilion,” as I have called this prototype, serves me now as a workspace and trailer-port.

Most housing professionals might see a laughable plaything. To my beginner’s mind, though, the Pavilion offers many possibilities and fits my present needs. I designed it as an agile, immediate, small home that, if I choose, can later be upbuilt into a more substantial, permanent, year-round home. I can add rooms to it, such as a kitchen and bathroom, or I can place it inside an existing room or building, to efficiently and flexibly offer its modular storage, sleeping platform, and desk/table. And because I can disassemble and reassemble the Pavilion as I like, I can put it in storage for a time or relocate it to stand as a backyard ADU, part of a village cluster, or even a rural off-grid cabin.

For me, this upbuild-able, disassemble-able, highly portable home is appealing, appropriate, and empowering—even joyful in a way. A self-built cabin like this indeed feels in some ways more fit and helpful to me than being handed keys and placed into the gold-standard, capital-A Affordable Housing solution: a new, subsidized, permanent apartment.

What’s more, the Pavilion uses just $500 in reusable materials, where the apartment costs about $500,000. But the law and our affordable housing practices, in their majestic equality, disdain homes like my Pavilion as “substandard.” They instead uphold human dignity by offering one lucky person a mayoral-class apartment. The ninety-nine others who are unhoused are offered only hope.

So, prioritizing both affordability and self-determined paths to stability, I would offer such housing kits to unhoused neighbors along with support to legally site and upbuild them. Such lightweight but capable housing is suited, I believe, to many people who need and want fluid, low-cost dwellings. To adapt that quote about fishing: Give a person a house, and you house them for now. Teach them to house themselves, and you house them for life.

3) Roll out the ultimate scalable infill: The Wheeler House vehicle-drawn dwelling

Have I successfully rattled any conventional American middle-class housing ideals yet? Well, let’s move on to what I’ll call the Wheeler House.

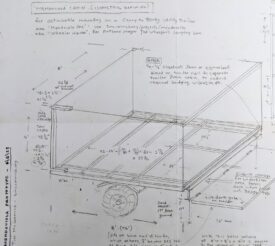

Less palatial than the 8’x10’ Summer Pavilion, this dwelling easily mounts on a 5’x8’ car trailer. In roof-down position, it appears to be a small tool or storage trailer about the height and length of a sedan.

The Wheeler House can park in a driveway, street space, or garage, yet also has sleeping and work space, a hinge-up roof, and a pop-out patio or deck. It also includes standing height inside, wash and shower space, and a composting toilet.

Wheeler Houses don’t need to stand alone. One or more could be used as movable work or sleeping spaces that are components in a larger dwelling compound. They can also offer versatile private, focus, or refuge spaces amid a larger village or co-housing context with shared facilities. Under Portland’s current zoning, a Wheeler House can also legally be used as a detached bedroom or an accessory structure in a backyard.

Another case where a Wheeler House might be rather handy is after, say, a massive Cascadia earthquake, if your home is gone or uninhabitable. A dwelling that’s secure, off-grid, and pullable by two people by hand or one on bicycle might be useful once the region’s petro-industrial complex has collapsed and gasoline and utilities are unavailable. In the meantime, you could have yourself a nice backyard studio, guest room, or fun micro-trailer to take down to the coast occasionally. Plus, perhaps you could house someone in need in your driveway.

That brings me to another possible use for the Wheeler House: dismantling homelessness. In Portland in July 2023, a new citywide camping ban made the habitations of thousands of the poorest Portlanders likely illegal. These residents became subject to citation and jail sentences overnight, even as it remains legally contested how this policy could be compliant with Federal court rulings and with Oregon law HB 3115, which require shelter or accessible space to be reasonably available.

Many argue, persuasively, that a lot of unsheltered people will not voluntarily go to today’s city-run shelters or don’t consider them reasonably available. This may be due to issues including inconvenient location, trauma from previous shelter experiences, restrictions on schedules or cohabitation, and prohibition of pets, possessions, and vehicles.

Basic-variant Wheeler Houses, including provisioning the trailer base and vehicle registration, could rapidly house hundreds or thousands of people for about $2,000 each. This would be a quickly deployable, customizable, and evolvable alternative to street tent camping or residence in broken-down vehicles parked on city streets. A complementing “Parking-Dwelling Permit” system could help manage allowed locations, vehicles, services such as garbage and waste, and good neighbor agreements.

Radical? Yes. But planners and housers are gradually coming around to seeing more legitimate possibilities in mobile dwellings. For more on such designs’ historical, cultural, and legal contexts, see my talk at the 2022 National Vehicle Residency Summit, “Vehicles as Housing, Housing as Vehicle.”

Dynamic housing for open futures

Marginally housed people like me know that there is loads of available space in the world. In North America, that is often thanks to sprawling and fractured urbanscapes, overbuilt parking lots, giant roadways, big houses, and little-used yards.

Our main obstacle in this crisis isn’t a lack of space. It’s our own shackled thinking. Paraphrasing Hamlet: we could be kings of infinite space, were it not that we dream poorly.

We need to challenge cultural assumptions that land use and buildings and housing placement must be permanent—that is, fixed in place and forever after—in order to be legitimate. This way of thinking, and the land use rules enforcing it, freeze up vast space and potential, often enshrining waste, disuse, and inequity. We urgently need to be building our lives, our homes, and our cities for permanent adaptability.

We don’t really need to suffer the endless thirst of scarcity, nor allow for so many the misery of unsheltered homelessness, when we live in this ocean of space. We all just need, at a given time, a place or two that suits us, fitting our diverse lives, needs, priorities, and preferences. There are ample ways for all of us and all of them, if we can open our eyes, imaginations, hearts, and policies and allow building from the bottom up.

Comments are closed.