Takeaways

In Cascadia, “fire weather” and a growing population are constants, and they are creating a lethal alliance.

Building wildfire-resilient communities by guiding growth away from fire-prone areas is key for climate adaptation. Instead, new housing developments are sprawling into the wildland-urban interface.

Growth management policies offer an important solution.

The residents of Bend, Oregon, used the state’s land use law to shrink by 70 percent a proposal to build thousands of houses in a fireplain and redirect growth to inside city limits.

This wildfire success story shows why Oregon’s land use law, despite having successfully protected farm- and forestland, has allowed more sprawl than intended. It took sustained community advocacy and future-looking city and county leadership to use the law to redirect growth away from a fireplain and nurture a climate-resilient city.

Find audio versions of Sightline articles on any of your favorite podcast platforms, including Spotify, Google, and Apple.

William Kuhn, who lost his Bend, Oregon, home in the Awbrey Hall Fire, has a warning: “Anyone who decides to live on the edge of the forest risks losing their homes. We know that.”

Once considered rare, the “fire weather” that fueled the 1990 Awbrey Hall Fire is now a fixture of Cascadia’s climate. “It’s not a question of if, but when fires come through,” said Boone Zimmerlee, Deschutes County’s fire-adapted communities coordinator.

Building wildfire-resilient communities is key for climate adaptation. As I recently documented, the best tool for the job is guiding growth away from areas of fire hazard, which I call fireplains. Building new homes within existing urban areas, or “infill,” is the safest solution, followed by compact development contiguous with existing city limits.

This is exactly what the residents of Bend, Oregon, did circa 2009, when they invoked the state’s landmark 1973 land use law and prevented houses from being built in a fireplain by instead directing growth inside city limits.

Across the state, Oregon’s land use law has been silently protecting life and property from wildfire. As Rory Isbell of Central Oregon LandWatch noted, “If you think of where the Labor Day fires burned a few years ago, up and down the Santiam, the McKenzie, and the Clackamas, if they’d had big, sprawling residential suburbs, the fires would have been a heck of a lot worse.”

Bend’s case shows how growth management policies can empower Cascadians to build wildfire-resilient communities. It also offers correctives to upgrade Oregon’s land use law, or at least to improve how it is used.

Growth is coming

Along with the rest of the West, Cascadia’s population is growing. To keep up with the influx, by 2040, Idaho needs to build about 660,000 new dwellings, and Washington will need an additional three million.

Population is growing fastest in areas abutting or intermixing with wildlands, called the wildland-urban interface (WUI). Specifically, people are flocking to fireplains, where wildfires naturally return every few decades.

Cascadians face a choice: continue to grow fastest in places that inherently require millions of dollars of firefighting every year, or direct growth into compact communities.

As a “nature lover’s dream,” the city of Bend, Oregon, is among the fastest growing cities in the United States. Over the next 50 years, the city will likely more than double its population, welcoming 120,000 new residents.

The big question: where will they live?

Pushing more houses into a fireplain: An ill-advised solution

Bend sits directly east of the seasonally dry Deschutes National Forest, putting it at the edge of a “frequent fire” zone, where wildfires naturally return every 35 years or earlier.

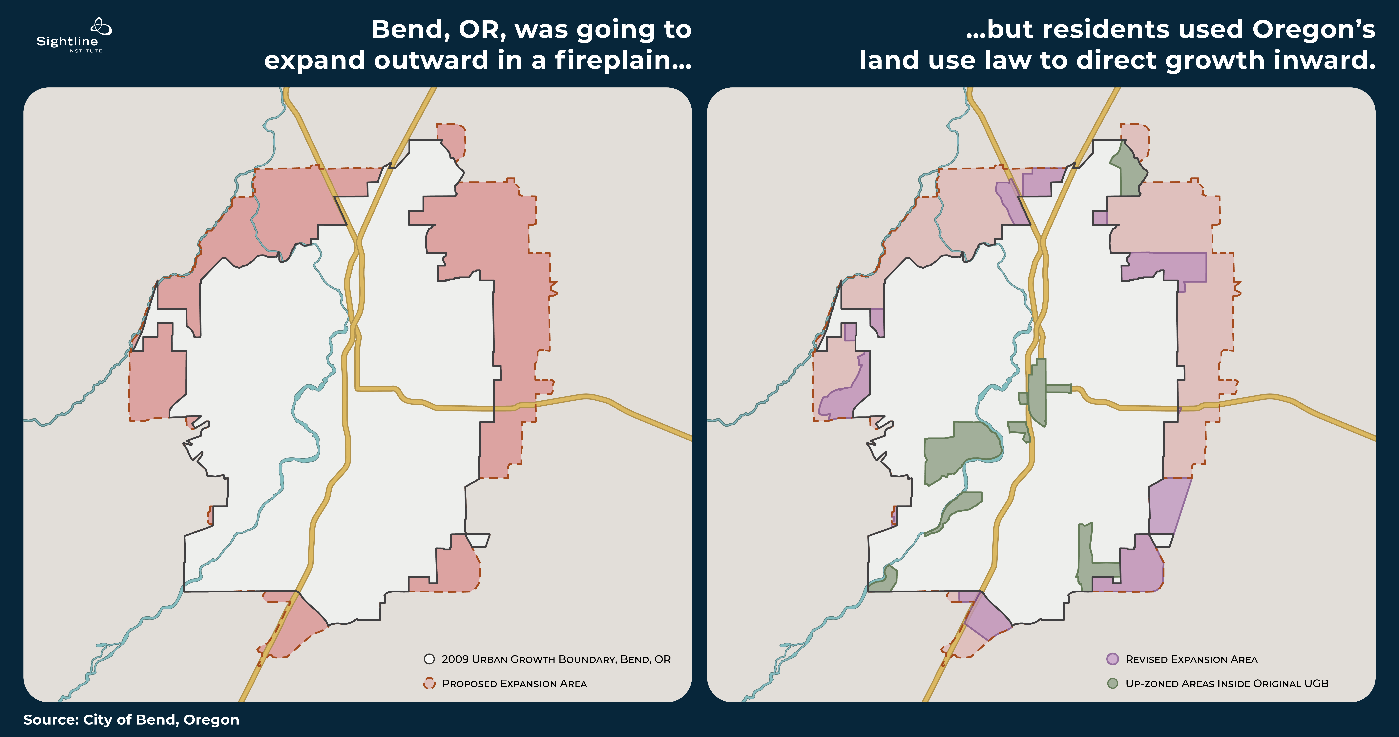

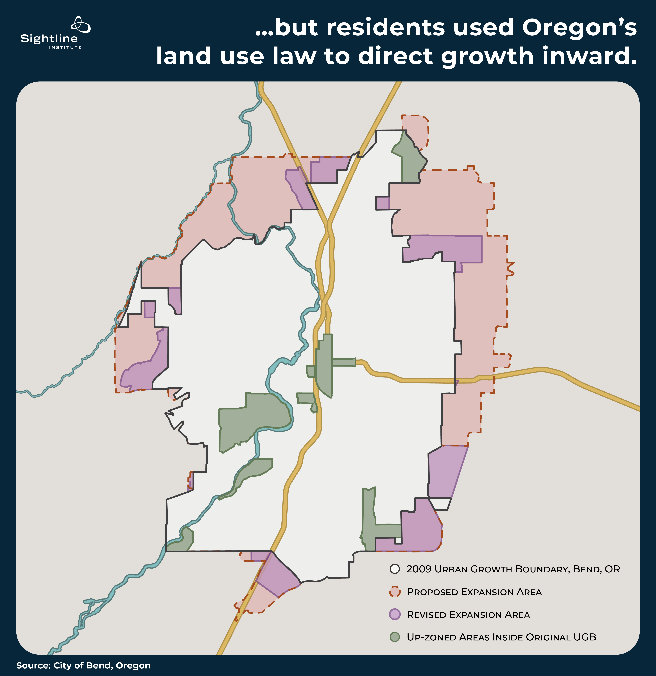

In 2009 the city of Bend and Deschutes County announced plans to expand Bend’s urban growth boundary and add as many as 5,000 new dwellings in this fireplain. The map below illustrates the proposed expansion. (The area within Bend’s original 2009 urban growth boundary is shown in white; the proposed expansion area is shown in pink.)

To the west of Bend, this proposed expansion overlapped with the footprint of the Awbrey Hall Fire that had burned homes and forced the evacuation of hundreds of people less than 20 years prior. The wind-whipped fire rebuffed the attack of fire crews fighting the main blaze’s 150-foot flames and the exponentially expanding spot fires ignited by flying embers. Within ten hours, the fire spread six miles, jumping over three major roadways and the Deschutes River.

The Awbrey Hall Fire would have been catastrophic had the wind shifted slightly and blown the wildfire head-on into downtown Bend, which could have caused a domino effect of house-to-house ignitions. But to the relief of residents and drivers idling in the backup of fleeing vehicles, a quirk in the weather saved the city. In the end, only 22 homes were destroyed, no lives were lost, and all fire crews came out safely.

Residents redirect new construction to safety

When Bend and Deschutes County proposed expanding the city’s urban growth boundary into this fireplain, residents objected. Not only was there a high fire hazard but converting this natural area to houses would also degrade the sensitive watershed around Tumalo Creek, which empties into the Deschutes River. The creek provides rare surface waters and riparian habitat in an area where porous soils mean that the Deschutes is mostly fed by groundwater.

To protect this natural area, residents used Oregon’s statewide land use law to appeal the new development. The law, in addition to preserving farm- and forestland, aims to limit urban sprawl by prohibiting subdivisions outside designated urban growth boundaries around cities and towns. Cities and towns set urban growth boundaries to accommodate about 20 years’ worth of growth, and the boundaries can only expand after the enclosed area is developed.

Bend residents and the nonprofit Central Oregon LandWatch successfully argued that the city had not considered existing opportunities for growth inside the current urban growth boundary. Over the past decades, Bend had grown outward subdivision by subdivision with very little multifamily construction and almost no mixed-use development outside the small historic downtown. So when city planners were forced to look, they found lots of room to grow within city limits.

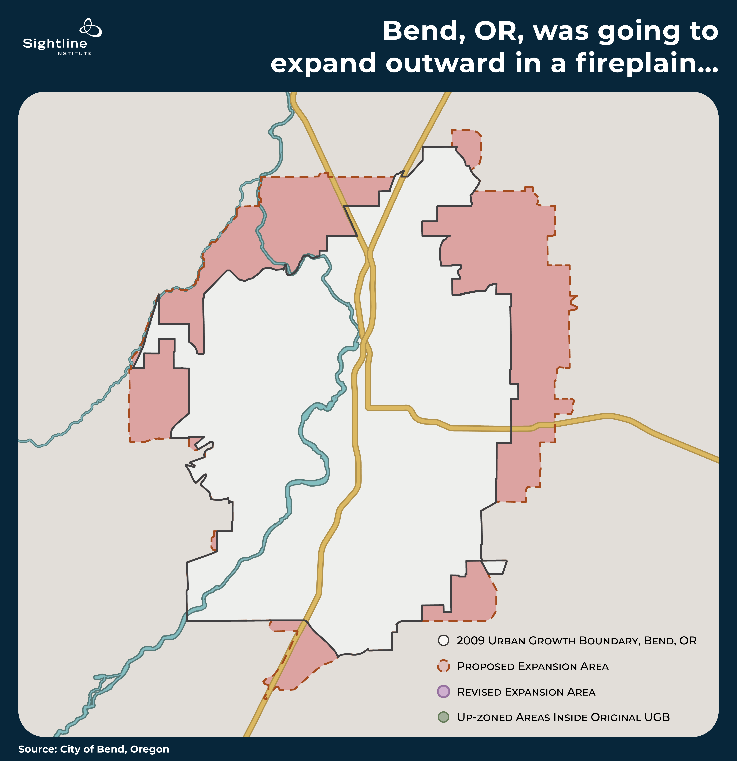

The city revised the plan, shrinking the growth boundary expansion by 70 percent and redirecting some housing growth inward by upzoningnine “opportunity areas” inside existing city limits.

In the heart of downtown Bend, within walking distance of shops, restaurants, and the river, a swath of underutilized and vacant land is now zoned for residential development up to six stories tall mixed with commercial and retail spaces. Bend also secured funding for climate-smart urban infrastructure such as school capacity, sidewalks, bike lanes, and street trees for its new residents. Bend’s Central District is becoming a place, as Isbell put it, “where people can actually live and not have to drive a car everywhere.”

Elsewhere in the city, Bend accommodated future growth by upzoning areas of single-detached housing to allow multifamily construction.

The map below contrasts the proposed expansion (shown in pink) with the much smaller footprint of the revised expansion (shown in purple). As before, the area of Bend’s original 2009 urban growth boundary is shown in white. Scattered within this existing boundary, the upzoned opportunity areas are in green.

The new plan drastically reduced the expansion of the urban growth boundary and limited the number of homes in the fireplain west of Bend, leaving room for a fire break between the city and Deschutes National Forest.

Thanks to David Brook & Susan Campbell for supporting a sustainable Cascadia.

Our work is made possible by the generosity of people like you.

While wildfire played a minor role in the appeal,developers to plaintiffs, credit the revised plan as a wildfire success story. In 2014, before the new growth boundary was finalized, the Two Bulls Fire blazed just west of Bend, burning 6,908 acres, prompting the evacuation of 635 households, and only avoiding the city by a lucky change of wind.

By redirecting houses away from the fire-prone Deschutes National Forest, Oregon’s land use law is saving lives and property, not to mention untold firefighting dollars.

Loopholes for leapfrogging

The full story is more complicated. While Oregon’s growth law has succeeded in protecting forest- and farmland, cities have sprawled more than intended, often in the low-density and leapfrog patterns that pose the greatest risk of wildfire damage.

First, by itself, the land use law would not have prevented Bend from sprawling into the fireplain. It was Bend residents’ wielding of this law that led to more compact growth. According to Isbell, “it took a lot of community organizing and advocacy to shrink the expansion.”

Second, exurban “exception areas” allow large-lot development outside growth boundaries. So even with an organized and resourceful community, Bend residents had to compromise. Like many Oregon cities, exurban land surrounding Bend was zoned for exception areas of minimum lot sizes of 2.5 to 10 acres per dwelling. (For reference, a 2.5-acre minimum restricts building to one house for every two-and-a-half football fields’ worth of land.) Without expanding the urban growth boundary, developers could build large-lot houses. This was their bargaining chip. On the other hand, without expanding the urban growth boundary, they couldn’t build the high-density subdivisions that are most profitable.

To prevent a landscape crisscrossed with large-lot development, residents negotiated to allow a greater number of subdivisions than existing exurban zoning would have permitted in exchange for a compact placement of development that minimized habitat loss and wildfire risk within a modestly expanded urban growth boundary.

Third, counties can authorize large-lot development (greater than one acre per house) within urban growth boundaries on land not annexed into a city. When this happens, subsequent subdivision of these lots becomes less likely and costlier, causing future development to leapfrog over these areas and accelerating the need for an urban growth boundary expansion.

Bend avoided this fate through explicit amendments in the Deschutes County subdivision code. Paul Dewey, former director of Central Oregon LandWatch, credits the success in part to collaboration among property owners, community advocates, and government officials.

“The county and the city have worked really well together,” he said. “Despite a wide spectrum of political views, this plan had far more public support than opposition.”

Climate-smart cities are fire-smart cities

On the other side of the equation, cities aren’t necessarily making infill easy. Where it’s allowed, local governments typically don’t nurture the growth of compact, vibrant cities.

With its revised growth plan, Bend upzoned some areas designated for single-detached housing and allowed vertical growth and mixed development in its walkable downtown. And since the Oregon legislature passed HB 2001 in 2019 and complementary reforms, internal growth will now be easier in all Oregon cities.

The pressure is on to house Oregon’s growing population, which will likely require about 30,000 to 40,000 new homes every year. By nurturing compact, vibrant, and climate-smart cities, land use laws help address the classic challenges of growth: coordinating infrastructure and public services, efficiently using land, and protecting natural resources.

They also safeguard against wildfires, which makes land use laws invaluable firefighters in our increasingly fire-prone region.