Takeaways

Electric transmission lines are essential to decarbonizing Cascadia, but the region’s transmission planning process is fractured, shortsighted, and perpetually behind the times.

With no long-term plan, BPA and utilities are building almost no new regional transmission lines, and the climate clock is ticking to get started on these lengthy projects.

Establishing a Western RTO could serve as solid scaffolding on which to build a new and improved transmission planning process in the Northwest but would take time and does not guarantee effective planning.

In this context, Cascadia’s leaders can take the wheel and convene a new regional transmission planning authority to answer the basic, but vexing question: How much more transmission capacity does the Northwest need to build to decarbonize?

Find audio versions of Sightline articles on any of your favorite podcast platforms, including Spotify, Google, and Apple.

Editor’s note: This is the first of three articles discussing the major challenges—planning, permitting, and paying for it—to building the transmission lines needed to transition to a cleaner energy future.

Electric transmission lines—those giant high-voltage wires that zap electricity across long distances—recently graduated from a fringe topic to a core challenge in the quest to decarbonize Cascadia. More leaders and climate hawks now recognize the centrality of transmission capacity to meeting climate goals, but that recognition has yet to yield action. The Northwest grid is jammed, and hundreds of wind and solar projects are languishing as a result. Neither the Bonneville Power Administration (BPA) nor Northwest utilities—nor anyone else, for that matter—is building the new transmission lines necessary to power millions of households and businesses in Cascadia with clean electricity. Why?

Much of the national conversation diagnosing impediments to new wires in the United States focuses on complex and lengthy permitting processes and their adjacent challenge: local communities’ opposition to new energy projects in their backyards. But a smooth permitting process is only one leg of the three-legged stool that successful transmission projects rest on. The other two are adequate planning and the right incentives for paying for the expensive lines.

Sightline looked into each of these three barriers in the unique context of Cascadia. This article, part of a series investigating the challenges of building transmission lines, focuses on planning.

If transmission lines aren’t planned, they aren’t built. And if transmission lines aren’t built, neither are new wind turbines or solar farms, prolonging our dependence on planet-destroying, war-fueling oil, coal, and gas. But the organizations that plan Cascadia’s future wires (largely, BPA and utilities) are plodding along the same way they have for years, ticking boxes and averting their gaze from the impending new demands on the grid. Meanwhile, Cascadia is on fire, and heatwaves are shattering temperature records around the world.

A different way forward is both imperative and entirely possible. Instead of betting our future on outdated, fractured, and myopic planning processes, Northwest leaders could establish a new regional transmission planning entity with the authority and resources to shepherd the region’s grid into the twenty-first century. Until they do, Cascadia’s climate ambitions grow more precarious by the year.

Cascadia’s transmission planning process: Fractured, shortsighted, and perpetually behind the times

“A goal without a plan is just a wish,” author and aviator Antoine de Saint-Exupéry is said to have written. If you ask anyone at BPA or a Northwest utility whether they are planning the grid for the future, they will assure you that they are. But plunge into the murky depths of transmission planning processes yourself and you will quickly become alarmed that Cascadia’s audacious climate goals may turn out to be mere wishes unless we chart a different course.

Since 2011 the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) has required all utilities that own transmission wires to participate in regional planning processes. In the Northwest, NorthernGrid leads that process. The group counts 16 members, including BPA, the region’s investor-owned utilities (e.g., Portland General Electric [PGE], Puget Sound Energy [PSE]), and some municipal utilities (e.g., Seattle City Light).1

But NorthernGrid is ill prepared for the task at hand: ushering the Northwest’s grid into an entirely new era dominated by climate change. The association has no full-time staff, no independent leadership, and is not accountable to state regulators or policymakers. It is essentially a small club of BPA and the biggest power utilities in the region that meets the letter, but not the spirit, of FERC’s planning requirements.

For evidence of these deficiencies, look no further than NorthernGrid’s only regional transmission plan to date, which spans 2021–31. The “plan” simply rubber-stamps all the regional transmission lines BPA and NorthernGrid’s utility members have proposed. It offers no new or different lines that might be imperative to meeting climate goals efficiently and cost-effectively. And it includes no interregional lines or wires proposed by non-utilities (known as merchant transmission lines). In other words, NorthernGrid’s “regional plan” copies and pastes whatever BPA and the utilities had already decided to do without examining what Cascadia needs to build to stave off an ever-worsening climate crisis.

NorthernGrid’s plan also ignores the impending surge of new clean energy resources Cascadia is counting on to decarbonize. The plan only looks as far as the next decade, rather than more prudently chalking out the next 20 years. And it relies on old data utilities developed before game-changing climate laws like Washington’s Clean Energy Transformation Act went into effect.

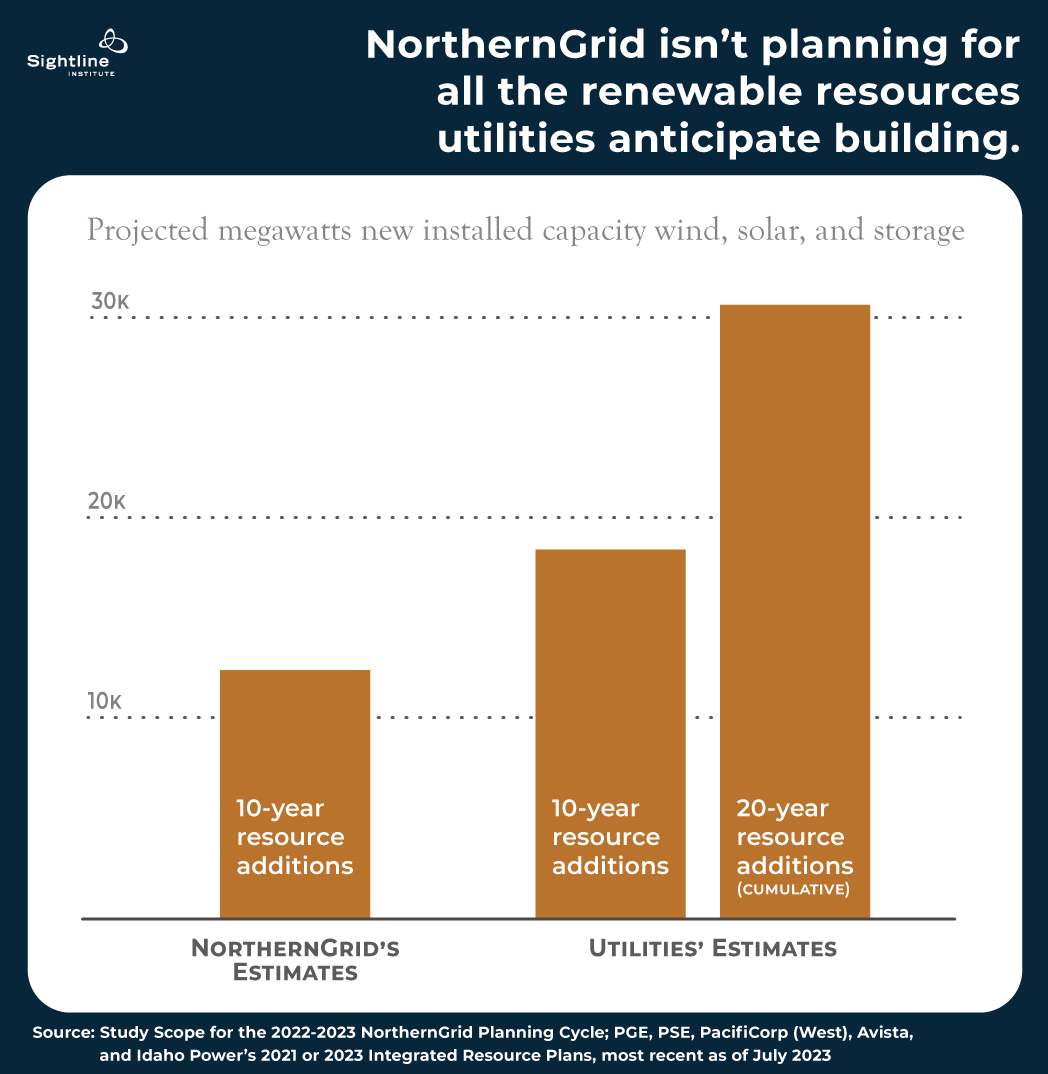

Sightline compared the data NorthernGrid is using to develop its forthcoming second regional transmission plan against the latest publicly available data in Northwest investor-owned utilities’ most recent integrated resource plans (IRPs).2 The chart below shows just how unhelpful NorthernGrid’s yet-to-be-released plan will likely be at providing a trustworthy road map to decarbonize the region’s grid. The bar at left represents the new wind, solar, and storage resources that NorthernGrid assumes the Northwest will add over the next decade. By contrast, the bars at right represent the new resources that utilities estimate they will need to clean up their portfolios over the next 10 and 20 years, according to their latest IRPs.3 NorthernGrid is not only lowballing the 10-year resource additions, but also wholly ignoring nearly 20,000 megawatts of new renewable energy the region is depending on to decarbonize in the subsequent decade.

Many of these renewable projects will require new transmission capacity to get off the ground, and new wires can take 10 or even 20 years to build. In this context, NorthernGrid resembles a driver planning for a weeklong road trip who decides what to pack based on last year’s balmy weather and only checks the three-day weather forecast. Meteorologists warn that a blizzard will hit in five days, but NorthernGrid ignores them, grabs a sunhat, and leaves the tire chains at home.

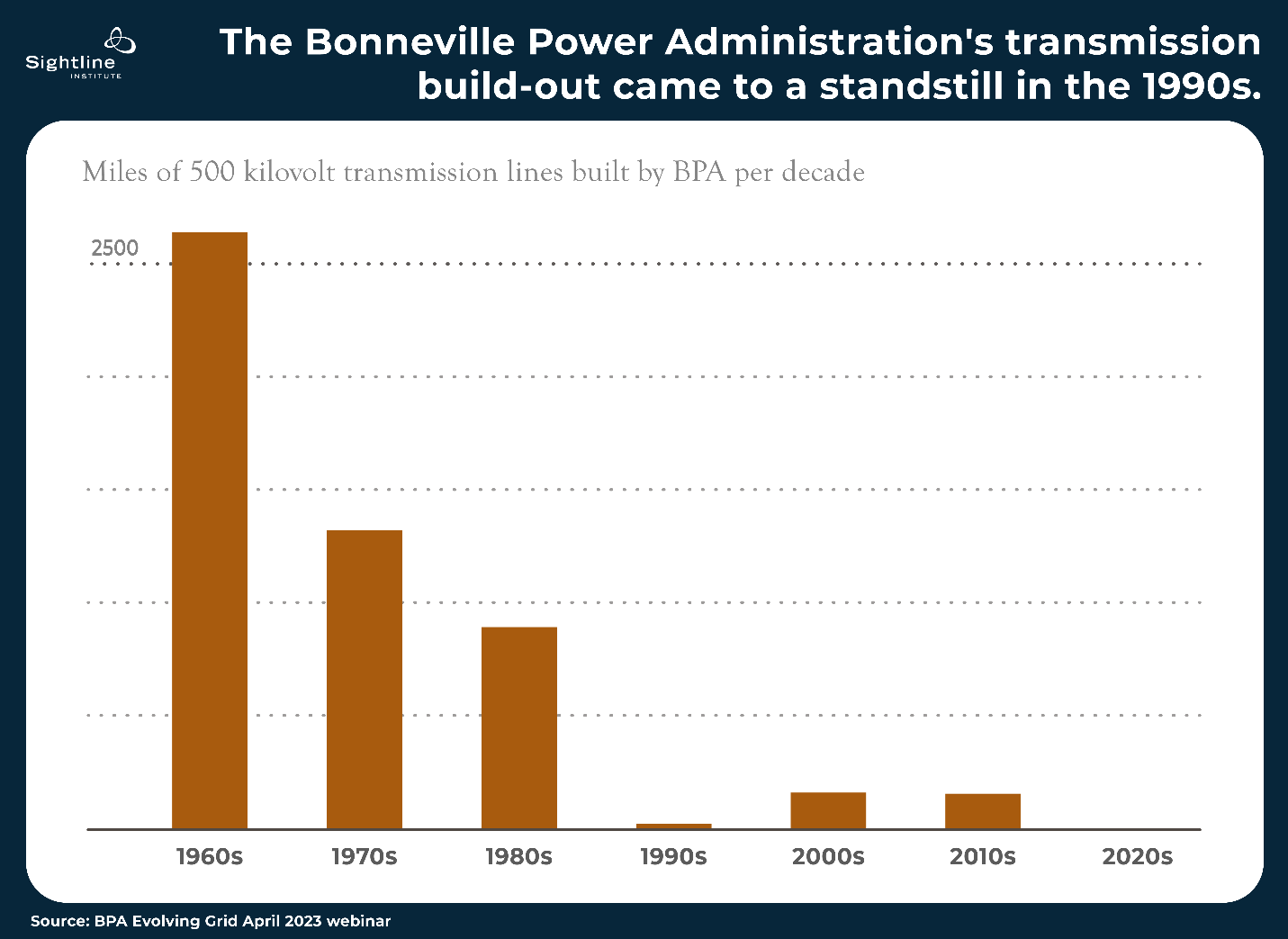

With NorthernGrid phoning it in, one might assume that BPA would step up. After all, BPA built thousands of miles of transmission wires in the 1960s and 1970s and now owns and operates 75 percent of the region’s high-voltage lines. Enjoying a full-time transmission planning staff and flush with more than $17 billion dollars in borrowing authority from the US government, BPA is the Northwest grid’s 500-pound gorilla. But BPA’s grid build-out screeched to a halt in the 1990s (see chart below). Each bar represents the miles of high-voltage transmission lines BPA built per decade since 1960.

Shortcomings in BPA’s planning process explain some of this standstill. Like NorthernGrid, BPA plans its transmission system only 10 years in advance and does not model climate change or climate policies when determining whether to build new lines and where to locate them. Instead, BPA is entirely reactive: if a wind or solar developer needs transmission capacity and commits to shelling out for a new line, BPA will consider the project and may include it in its transmission plans. It will also build new capacity if necessary to meet reliability standards. But it doesn’t proactively plan much of anything to help the region achieve climate targets.

In April 2023 BPA announced it is considering six transmission upgrade projects that it claims will be sufficient for Oregon and Washington to meet their respective 2030 clean electricity targets. But BPA has refused to publicly share any data or analysis to defend these assurances, despite repeated requests from Sightline and others. It also claims to have modeled the grid’s needs even further into the future but has stonewalled Sightline and others who have asked for details. BPA confirmed its commitment to these projects in a July 2023 press release. However, the projects still need to go through environmental review, and BPA will only begin construction if developers agree to pay for the projects.

This leaves only one longer-term transmission planning effort in Cascadia today, which doesn’t inspire confidence. The Western Power Pool’s 20-Year Extended Planning Horizon Study is a voluntary effort by BPA and most Northwest utilities that has already fallen months behind its own deadline. Study participants have yet to announce a new expected release date for draft results.

A Western RTO to the rescue?

One idea to address regional planning shortcomings is already on the table. In April 2022 FERC proposed a new rule that would require regional planning entities, including NorthernGrid, to map out transmission systems 20 years out instead of 10 and to better account for “changing generation mix, shifting demand patterns, and extreme weather.” However, the proposal is in purgatory; FERC is currently stuck in partisan gridlock. After Senator Joe Manchin withheld his support for the confirmation of FERC Chairman Richard Glick to a second term, only four of FERC’s five seats are full, evenly split between Democrats and Republicans.

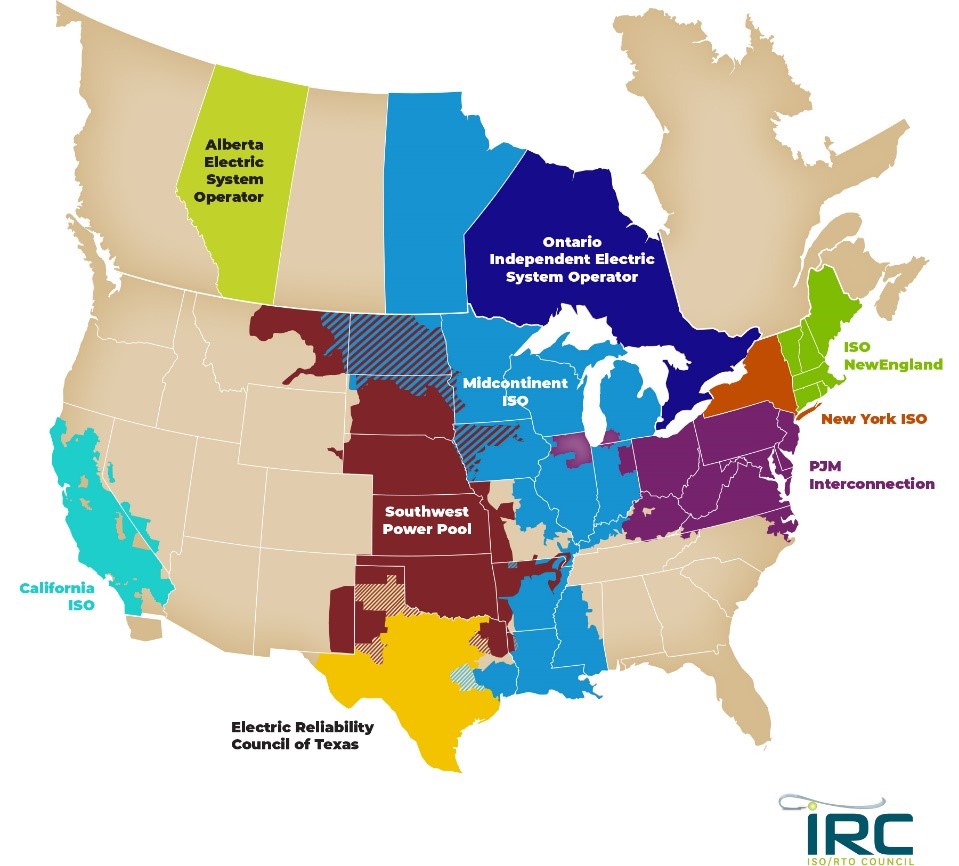

Even if FERC does finalize the rule, it might not help much in the Northwest given our lack of a Regional Transmission Organization (RTO), according to Ari Peskoe, Director of the Electricity Law Initiative at Harvard Law School. RTOs are nonprofit entities responsible for, among other things, maintaining the grid and planning new transmission lines. (For a good primer on RTOs, see this 2021 study that the Oregon legislature commissioned.) RTOs manage the grid for about two-thirds of the total US electricity load (see Figure 1 below).

Figure 1: The Northwest is unusual in North America in its lack of an RTO.

RTOs differ from planning assemblies such as NorthernGrid in that they have their own staff and board and “at least some semblance of an independent organization,” Peskoe said. And some RTOs already boast proactive long-term transmission needs assessments even without the FERC rule change. California’s RTO, the California Independent System Operator (CAISO), released the gold standard of this type of analysis in 2022.4 (CAISO is the only RTO in the West, created by the California legislature in 1998.) Rather than cobbling together individual utility transmission plans, as NorthernGrid does, CAISO spearheaded its own study. CAISO worked backward from the state’s 100-percent clean electricity law, derived anticipated changes to electricity load and resource mix, and then identified $30 billion worth of transmission upgrades and build-outs needed to meet the state’s 2040 goal. Technically, CAISO’s “outlook” is not, in transmission-speak, a “plan” because it does not determine which transmission projects to build. Nonetheless, CAISO’s analysis gives utilities, regulators, and other transmission developers in California a clear road map.

Since 1996 multiple attempts to create an RTO in the rest of the West have failed, but momentum may be shifting. A 2021 US Department of Energy Study found that a Western RTO would lead to benefits of up to $2 billion annually by 2030. That same year, the legislatures in Colorado and Nevada required utilities in those states to join an RTO by 2030. And BPA and Western utilities are taking baby steps toward regional integration. The Western Energy Imbalance Market, for example, now allows utilities to buy and sell energy across the region in real time, and the Western Markets Exploratory Group is a new collection of utilities evaluating options for regional electricity market solutions.

An RTO could serve as solid scaffolding on which to build a new and improved transmission planning process in the Northwest. Although a worthy goal, an RTO does not, by itself, automatically lead to effective planning.

“Utilities are very influential in the RTO process,” Peskoe cautioned. He explained that each RTO has its own structure and that some have been more successful at proactive regional transmission planning than others. And setting up an RTO across the West would take years due to contention around the governance of multiple utilities across multiple states, not to mention BPA, which is not under state or FERC jurisdiction. Realistically, a Western RTO is unlikely to emerge until the late 2020s to 2030s, according to Michael Wara, Director of Climate and Energy Policy at the Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment.

With wildfire smoke polluting our air and overheated oceans decimating marine ecosystems, the Northwest doesn’t have until 2030 to develop a plan. The only big new transmission line in our region right now (the Boardman to Hemingway project) won’t break ground until later this year. Project backers first proposed it almost 20 years ago.

We need a better way to plan, and we needed it yesterday.

The best hope: State leaders taking the wheel

With NorthernGrid and BPA asleep at the wheel, it’s time for Cascadia’s leaders to move to the driver’s seat. They are arguably the best hope for unleashing construction of transmission wires. Legislators have already taken some steps, including Washington passing a law in 2023 to extend utility planning to 20 years instead of 10 and establishing a Transmission Corridors Work Group that released a report in 2022 outlining principles for building new transmission lines in the state.

But these efforts are small potatoes compared with what the climate crisis demands. The governors of Idaho, Montana, Oregon, and Washington would be smart to establish and convene a new regional transmission planning authority instead of relegating this most-essential task to NorthernGrid, BPA, and Northwest utilities. The primary purpose of the new assembly would be to answer the basic but currently vexing question: How much more transmission capacity does the Northwest need to decarbonize? A successful outcome would identify where transmission lines could and should go to leverage renewable resources efficiently and minimize harmful impacts on sensitive ecosystems while protecting tribal treaty rights.

To be effective, the planning authority’s leadership would include tribal representatives, environmental activists, and state representatives, who today are completely sidelined during transmission planning discussions. State legislatures and the Northwest congressional delegation could demand BPA and utilities’ active participation, including requiring that they provide any forward-looking analysis and modeling they have already performed. Indeed, several groups, including the NW Energy Coalition are already meeting with leaders to float the idea for such a forum. With independent oversight, adequate technical staffing, and sufficient resources, this new entity could likely take mere months to accomplish what NorthernGrid and BPA haven’t in years.

With a plan in place, state leaders could choose to take even more aggressive action, such as building lines themselves or directly authorizing utilities to do so, as Nevada legislators did in 2021 with NV Energy’s (controversial) GreenLink project.

Time to map the course

Coral reefs are dying, species are facing extinction, and millions of people are choking on smoky air. But the institutions in charge of some of Cascadia’s most critical clean energy infrastructure are acting like they don’t notice. Today’s transmission planning processes are reactive, shortsighted, insular, inscrutable, and willfully ignorant of impending changes to the region’s energy system. As a result, the Northwest has no real transmission plan, nor a process for developing one.

Northwest states can no longer rely on NorthernGrid, BPA, or even a long-elusive Western RTO to prepare a realistic and independent transmission plan quickly enough. It’s time for a new approach. State leaders can step in and convene a new Cascadia transmission planning body. With the right capacity, expertise, and commitment to combatting the climate crisis, this new group can map directions for the future grid. Once we know (and trust) where we’re going, we can finally hit the road.

Comments are closed.