Takeaways

Without pruning the gas system, gas customers who are least able to electrify their homes will face a growing risk of skyrocketing gas costs.

Decommissioning gas pipes is possible, but requires electrifying entire neighborhoods rather than today’s scattershot approach.

As a first step, legislators or regulators need to eliminate gas utilities’ “obligation to serve,” require that utilities propose neighborhood electrification instead of replacing aging gas pipes, and protect ratepayers from gas companies’ unwise investments in gas system expansion.

Ultimately, electrifying whole neighborhoods and shrinking the gas system will require new utility incentives and/or new targeted public funding to achieve the scale and pace climate change requires.

Find audio versions of Sightline articles on any of your favorite podcast platforms, including Spotify, Google, and Apple.

Cascadians are swapping gas furnaces for heat pumps, gas stoves for induction cooktops, and gas dryers for electric ones. The “electrify everything” movement is accelerating, spurred by new federal, state, and local incentives.

But when and how are we going to start pruning the gas system accordingly? Without shutting down gas infrastructure in tandem with electrification, an ever-shrinking number of gas customers will face ever-ratcheting costs to maintain a bloated gas system. Renters and low-income people who face the greatest hurdles to electrify are at the most risk of this so-called “death spiral.”

Thankfully, there is a better way: strategic gas decommissioning paired with neighborhood electrification. In this world, all the buildings in a neighborhood or area electrify, as opposed to today’s scattershot approach. Then, the gas utility shuts off that part of the system, rightsizing its infrastructure to fit the new, smaller number of gas customers.

Cascadia has yet to start decommissioning gas infrastructure or electrifying whole neighborhoods, but early work underway in California, Colorado, and New York offer some insights to get going. At a minimum, leaders in Cascadia who are committed to clean, healthy buildings and an equitable transition off of gas would be smart to:

- Clarify or eliminate gas utilities’ “obligation to serve,”

- Require gas utilities to propose areas ripe for decommissioning and neighborhood electrification instead of replacing gas pipes,

- Incentivize decommissioning and neighborhood electrification while protecting ratepayers, and

- Shield gas customers from future stranded gas assets.

Let’s take these steps in turn.

1. Clarify or eliminate gas utilities’ “obligation to serve”

All states and provinces of Cascadia (and all 50 US states) require gas utilities to provide service to any customer in their territory who wants it.1 These “obligation to serve” laws used to make sense. They prevented monopoly utilities from discriminating against customers who were not profitable to serve, like people in low-density areas or those who use only small amounts of gas. And they helped lower gas customers’ bills by spreading fixed infrastructure costs over more households over decades, a model possible for a gas system that exists in perpetuity.

But we no longer live in a world where the gas system can last forever. And electric alternatives abound for every residential need currently met by gas. The obligation to serve—or, at least, regulators’ interpretation of it—is getting in the way of strategic gas decommissioning.

“A single customer can tank a project,” explained David Sawaya, Senior Manager of Decarbonization Strategies at Pacific Gas & Electric (PG&E), California’s largest utility, at a 2021 webinar organized by the California Energy Commission (CEC). CEC is funding a roughly $2 million, two-year body of research to identify potential pilot sites in northern and southern California for strategic gas decommissioning and neighborhood electrification.2 Given the obligation to serve, “every single customer has to agree to electrify” for decommissioning at the neighborhood scale to be possible, Sawaya continued. With recent uproar over an imaginary US ban on gas stoves, it’s not hard to conceive of a single gas system hold-out.

Obligation-to-serve laws are nebulous enough that the issue could be resolved through regulation alone, Professor Heather Payne, an expert on regulatory policy at Seton Hall University School of Law, told Sightline. Payne argues that a state’s Public Utility Commission (PUC) could do away with the obligation to serve simply by shrinking gas utilities’ service territory once the PUC identifies an area ripe for strategic decommissioning and neighborhood electrification. “Regulators gave service territories and they can take them away,” she emphasized.

But legal challenges from utilities or consumers could follow. This risk of lawsuits might warrant proactive clarification from state legislators that a utility’s obligation to serve is not equivalent to the right to gas, Claire Halbrook, Director at the decarbonization nonprofit Gridworks, told Sightline. (Gridworks is one of the CEC-funded groups researching potential strategic gas decommissioning pilots in Northern California.) Instead, legislators could clarify that the obligation to serve means the right to energy.

The 2023 New York legislature considered a bill that would get rid of that state’s obligation to serve, noting that it is “a major obstacle to utilities developing neighborhood-scale building decarbonization projects.” Washington legislators, too, have attempted to revise gas utilities’ obligation to serve at least twice (in 2021 and 2023), to no avail. Legislators in the Evergreen State would be smart to reconsider similar bills next legislative session, as would their peers across Cascadia.

2. Electrify neighborhoods instead of replacing gas pipes

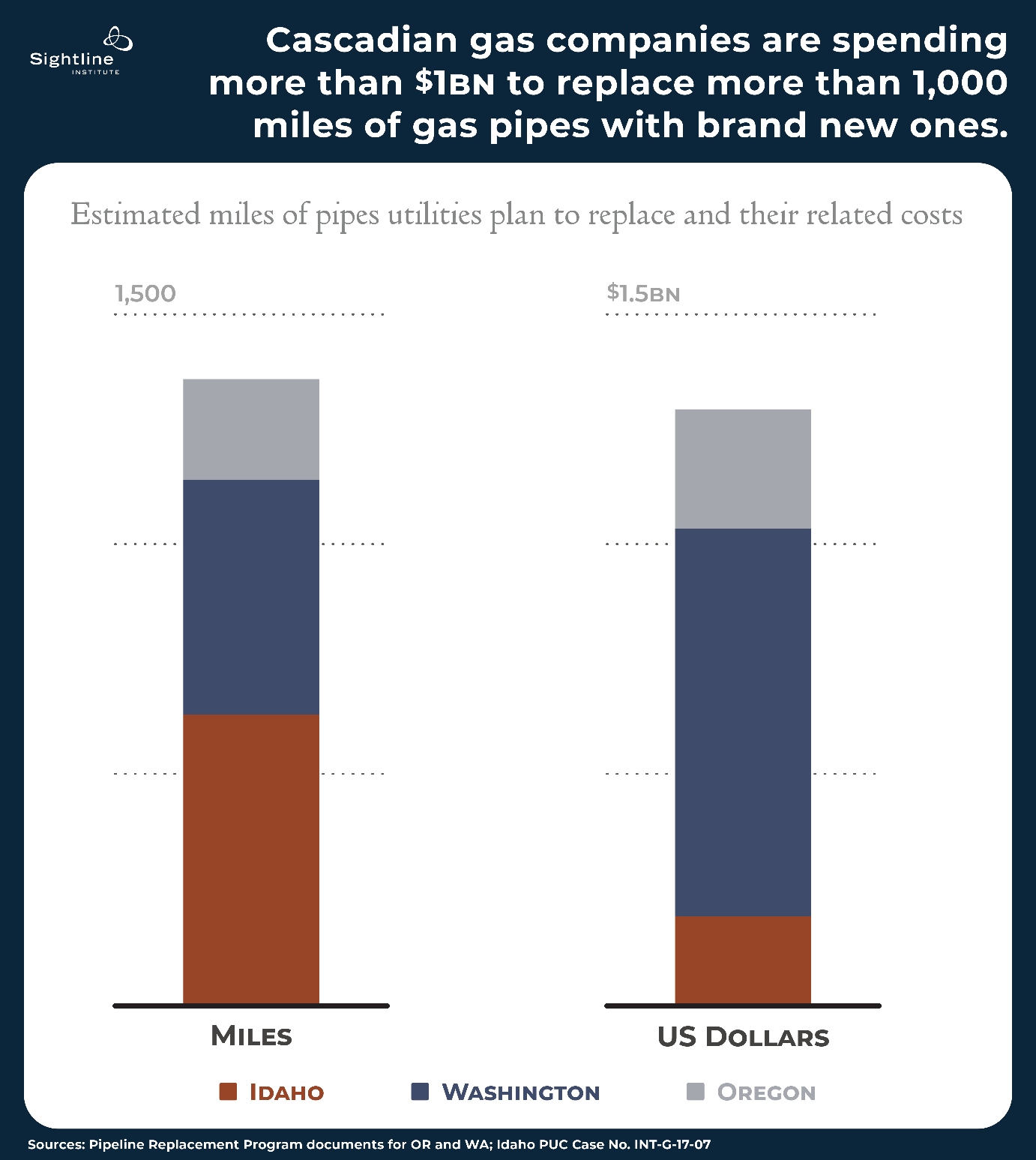

Gas utilities across Cascadia are spending billions of dollars to replace hundreds of miles of aging or leaky pipes. Avista, Cascade, Intermountain Gas, and Puget Sound Energy (PSE) combined plan to spend more than $1 billion of ratepayer money to install more than 1,300 miles of replacement gas pipes in Oregon, Washington, and Idaho alone over the next decade, as shown by the chart below.3 That’s the distance from Seattle to Portland, almost four times over.

These replacement pipes will last more than 50 years, decades past when Cascadia needs to wean itself off of gas. Part of what drives this massive spending, which gas customers pay for through their utility bills, is federal and state safety regulations. But regulators also financially motivate utilities to spend massive sums on new infrastructure projects—capital spending is the only way utilities turn a profit.

Traditionally, regulators have not required utilities to analyze “non-pipeline alternatives” (NPAs) such as neighborhood electrification that could mitigate the need for replacement gas infrastructure. That’s even the case in Washington and Oregon, where regulators require gas utilities to file long-term plans detailing how many miles of aging pipes they plan to replace and by when. (Regulators in Montana, Alaska, Idaho, and British Columbia do not require utilities to file pipeline replacement plans.)

But the status quo is starting to change in a few places, and Cascadian regulators could take note.

For example, the New York Public Service Commission adopted new gas planning rules in May 2022 that require gas utilities to file long-term plans every three years.4 As part of the rules, utilities must annually identify “the locations of specific segments of LPP [leak-prone pipes] that could be abandoned in favor of NPAs.” Similarly, the Colorado PUC issued new rules in December 2022 that require utilities to analyze non-pipeline alternatives for any new business and capacity expansion projects, though they unfortunately face no such requirements for replacement or repair projects. And staff at the California PUC recently put forward a draft gas decommissioning framework recommending that regulators in that state require gas utilities to analyze NPAs for any non-urgent repair or replacement projects. The Commission has not yet adopted final rules.

Cascadian leaders will need to figure out the right regulatory venue for following and, better yet, building on other states’ efforts. Regulators could require gas utilities to propose high-potential areas for decommissioning and neighborhood electrification as part of utilities’ regularly filed Integrated Resource Plans.5 Or they could require the same analysis in new, separate, long-term gas infrastructure proceedings. The former has the benefit of not piling more processes onto already busy regulators, but the latter may make it easier for both regulators and the public to evaluate specific gas infrastructure projects against non-pipeline alternatives.

In the absence of proactive regulatory changes, lawmakers could require new, forward-looking gas system planning that would promote strategic decommissioning and neighborhood electrification. In Colorado, the 2021 legislature’s “clean heat plan” law catalyzed the Commission there to issue that state’s new gas planning rules.

3. Incentivize decommissioning and neighborhood electrification while protecting ratepayers

Even with state and federal discounts on climate-friendly stoves, dryers, and heaters and on upgraded electric panels, neighborhood electrification will be expensive. Households that make more than 150 percent of an area’s median income are ineligible for the Inflation Reduction Act’s (IRA) electrification rebates, for example, but still may not be able to afford a full suite of upgrades. (These higher-income households can still take advantage of the IRA’s tax refunds.)

A consensus is lacking for who should front the costs for neighborhood electrification and whether they should be able to make money doing so. Below are three potential options (though not mutually exclusive or exhaustive) and Sightline’s initial perspectives on the pros and cons of each. Ultimately, Cascadian leaders will need to balance decommissioning gas pipes and electrifying neighborhoods at the urgent pace and scale that climate change demands with protecting ratepayers from inequitable and unjust energy costs.

Option A: Gas utilities pay (via their ratepayers), with or without a profit incentive

Gas utilities could use the money that they otherwise would have spent on new or replacement pipes to pay for neighborhood electrification instead. This is an idea some groups like the think tank Rocky Mountain Institute (RMI) have suggested in response to the California PUC’s staff proposal on strategic decommissioning. (Remember, anything utilities spend is ultimately passed on to their customers through energy bills, if regulators approve it.)

And RMI and others go a step further: to stimulate gas utility action, they suggest regulators consider allowing gas utilities to count electrification costs as “regulatory assets.” This treatment would enable the utility to earn a rate of return on these projects that normally they would not. In line with this idea, the New York PUC recently approved a request by ConEdison, the combination gas and electric utility serving New York City and Westchester County, to earn a rate of return on its non-pipeline alternative programs. ConEd identified 21 gas mains serving 320 households that could be retired in favor of electrification. (ConEd did not reply to Sightline’s request for information on the current status of these projects.)

Following in ConEd’s footsteps, in December 2022 Pacific Gas & Electric (PG&E) proposed a pilot to electrify 391 buildings on the California State University Monterey Bay campus. The utility says it would otherwise need to replace aging gas infrastructure on the campus, for which it would turn a profit. Thus, PG&E has asked the California PUC to treat the $17.224 million it plans to spend on electrification and decommissioning as regulatory assets. If the California PUC approves PG&E’s proposal, the utility would profit roughly $12 million from the project; PG&E’s gas customers would pay the utility back through their gas bills. PG&E estimates the project would still save its customers about $1 million compared to replacing the gas infrastructure. As of May 2023, the project is on hold following new leadership at CSU Monterey Bay.

Allowing gas utilities to get into the business of neighborhood electrification and to line their pockets doing so could galvanize them to use their scale and access to capital for good. In this world, gas utilities could act similarly to green banks, helping to finance the energy transition. Regulators and policymakers could also spur utility action in ways other than treating electrification costs as regulatory assets. For example, Washington House Bill 1589, which the 2023 legislature did not pass, included several possible sweeteners for Washington’s biggest utility, Puget Sound Energy (PSE), in exchange for the wind-down of the company’s gas business. The carrots included allowing the utility to earn a rate of return on power purchase agreements and upping the profit the utility could make on electric assets.

But offering gas utilities financial upsides for electrification from ratepayers’ wallets comes with risks. “You need savings from the strategic decommissioning projects to offset some of the gas rate increases we’re seeing,” explained Claire Halbrook of Gridworks. She worries about scenarios in which a neighborhood electrification project costs the same as a gas pipeline replacement project would have, and the utility passes on those equivalent costs to gas customers. Doing so would obliviate one of the biggest reasons for gas decommissioning: rightsizing gas system costs to a shrinking number of gas customers. (Note: GeoNetworks, which Sightline has written about previously, as a neighborhood electrification option may avoid this problem because the electrifying households would remain customers of the former gas, now “thermal,” utility. But, depending on the cost of installing GeoNetworks, which is not yet known, unsustainably high rates to gas/thermal customers could still be a risk.)

If regulators choose to financially motivate gas utilities to embark on decommissioning and neighborhood electrification, they can still mitigate the risk of unjust and inequitable gas rates. For example, regulators could allow gas utilities to earn a lower profit (but still something) than they would have on the gas infrastructure project and/or shorten the payback period for the electrification costs compared to traditional gas infrastructure. This latter option would save customers money compared to a traditional gas infrastructure investment because the costs would be spread over more customers upfront (before they leave the gas system) and the investment would accrue fewer years of interest. (A similar concept is the lower total cost of a 15-year versus a 30-year mortgage.) Indeed, several groups, including the Sierra Club, are pushing the California PUC to lower how much financial gain PG&E proposes collecting from its proposed California State University Monterey Bay pilot.

Option B: Electric utilities pay (via their ratepayers), with or without a profit incentive

Alternatively, or perhaps in addition, the same model as option A could apply to electric utilities instead of gas ones. Under current regulatory frameworks, investor-owned electric utilities will already recover with profit any “front-of-the meter” infrastructure upgrades associated with neighborhood electrification.6 But just like gas utilities, they couldn’t today profit on anything regulators don’t count as a regulatory asset.

As they could with gas utilities, regulators could decide to keep the current ratemaking model and still require electric utilities to pursue neighborhood electrification with no financial incentive. This was the approach California regulators took to a pilot converting homes from wood or propane to gas or electricity in the San Joaquin Valley.

But just as in the case of gas utilities, allowing electric utilities to turn a profit could encourage them to prioritize and pursue neighborhood electrification projects. The big risk to doing this is it could cause electricity rates to rise, potentially undermining electrification writ large.

“Especially in California, where we have really high electric rates, rates are sending a signal that is discouraging electrification,” Kiki Velez, Equitable Gas Transition Advocate at NRDC, told Sightline. She worries that any additional costs on the electricity side will be both inequitable and self-defeating. That may be somewhat less of a concern in Cascadia, where retail electricity rates are roughly half what they are in California. Still, energy inequity is a concern here; in Washington, for example, a quarter of households are energy-burdened, meaning they spend more than 6 percent of their household income on energy bills. Regulators would need to carefully design any utility incentives in a way that avoids worsening these inequities, and better yet, alleviates them.

Option C: The public pays by geographically targeting incentives

Finally, the cost for neighborhood electrification could be fully removed from utility rates, which are a notoriously regressive system. Instead, a new progressive tax or geographically targeted existing incentives could foot the bill. “We should focus electrification dollars on targeted electrification and not on scattershot electrification,” Claire Halbrook of Gridworks told Sightline.

Thanks to Salli Blevins for supporting a sustainable Cascadia.

Our work is made possible by the generosity of people like you.

And indeed, a lot of money is already on the table. US states in Cascadia will collectively receive more than $250 million from the IRA to distribute for home electrification. And both Oregon and Washington offer millions of dollars for heat pumps and other clean appliances. Individual utilities in Cascadia, too, offer incentive programs (see here, for example).

But to date, legislators and state agencies have not targeted this funding toward areas with a high potential for strategic decommissioning and neighborhood electrification. (Most states haven’t figured yet out how they will disburse the new IRA money.) Doing so would require collaboration between the state agencies receiving and distributing these funds and the utilities pursuing the neighborhood electrification projects. What’s more, leaders will need to grapple with how to maintain a focus on helping low-income customers electrify while also targeting neighborhoods with high potential for strategic gas decommissioning, which may not be one and the same.

4. Draw a “bright line” to shield ratepayers from stranded assets

Decommissioning aging pipes instead of replacing them is the most straightforward opportunity facing utilities to shrink the gas system. But soon enough regulators and utilities will need to reckon with shutting down gas pipes that have not yet reached the end of their expected lifespan.

Who bears the cost of these “stranded assets” is ultimately up to regulators and whether they decide utilities made infrastructure investments “prudently.” 7 Regulators can allow utilities and their shareholders to fully get paid back (i.e., “recover”) from ratepayers the value of stranded assets, either with or without a rate of return. Alternatively, they can decide that utility shareholders should eat the cost of imprudently made investments, absolving ratepayers of responsibility. Regulators have pursued each of these options in other cases, including for canceled nuclear plants or other types of power plants.

Arguably, most, if not all, recent utility investment in new gas infrastructure could be considered “imprudent” given widespread global acknowledgement of the need to rapidly transition off of fossil fuels, including gas. But regulators continue to acknowledge utilities’ plans to spend more on gas and allow them to incorporate gas infrastructure spending in their rate base. These regulatory actions would give weight to any utility’s demand that it be fully repaid on its investments.

Thus, Cascadian regulators could make explicit a “bright line”—a time after which utilities should not expect to be paid back by gas customers for installing new, polluting infrastructure. A conservative bright line would be after a state or province passed an economy-wide climate policy. That would mean utilities and their investors would be on the hook for any gas infrastructure spending made after 2007 in British Columbia, after 2020 in Washington, and after 2021 in Oregon that wasn’t necessary to resolve an urgent safety or reliability issue.

Still, that would leave billions of dollars of assets in a gray zone. Who should pay for the assets that utilities installed after climate change was widely understood but before the states where the companies operate passed policies to do anything about it? And what should regulators do in the parts of Cascadia where lawmakers haven’t passed economy-wide climate policies?

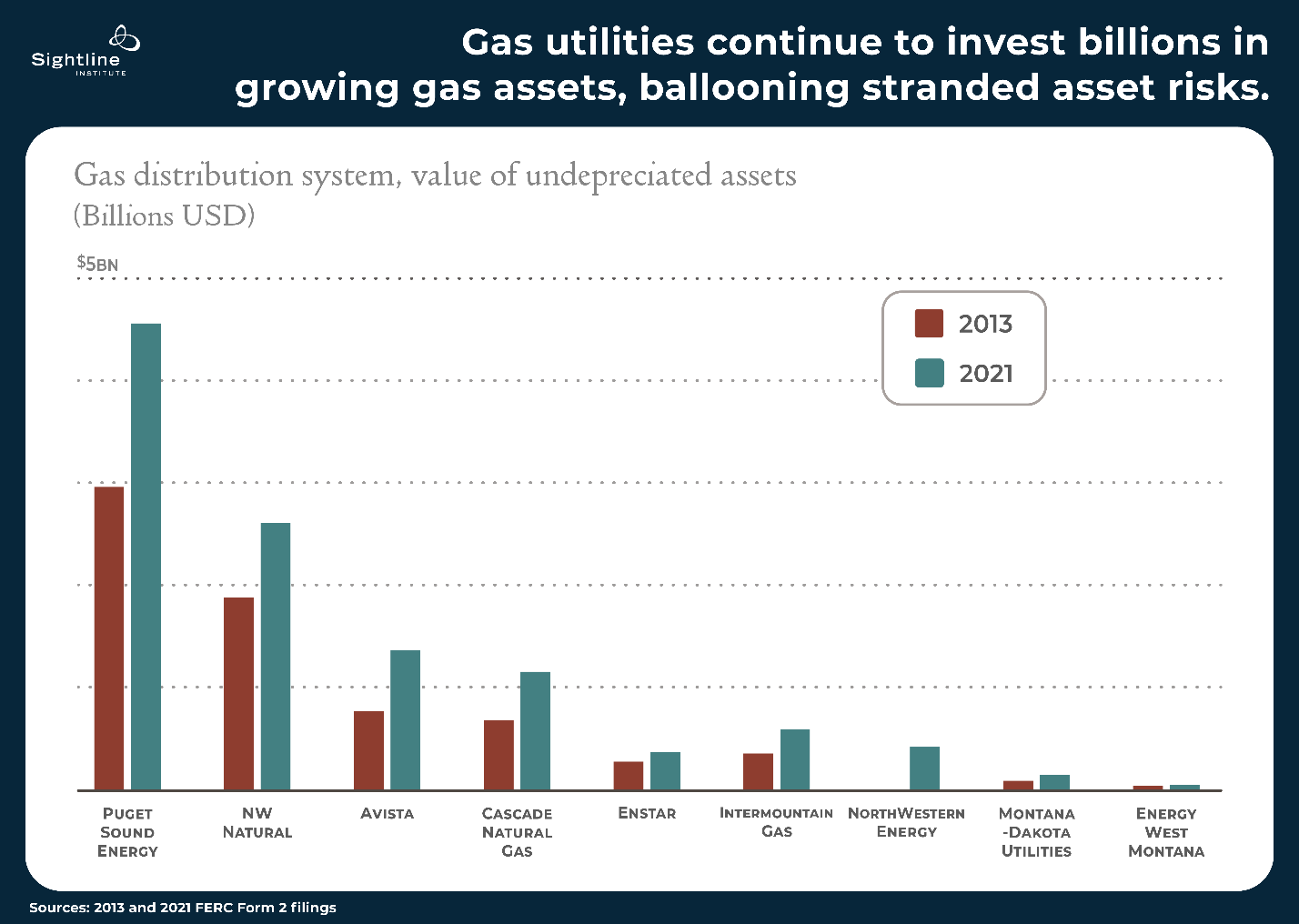

As an illustrative example of the continually worsening stranded asset risk, gas utilities across Cascadia increased the value of their undepreciated gas distribution system assets by more than $4 billion between 2013 and 2021, from about $7 billion to $11.2 billion. Gas distribution system assets, – such as gas pipelines, – lose value over the course of their useful life—that is, they i.e., depreciate. When gas companies install new infrastructure, the total value of the company’s assets that have not yet depreciated grows, since that infrastructure is at the very beginning of its useful life. Thus, a growing undepreciated asset value means more new pipes and other gas infrastructure. (The breakdown by utility is shown by the chart below, with red bars representing undepreciated assets in 2013 and blue representing them in 2021.) This means the amount that gas ratepayers may be on the hook to pay back to utilities and their investors is now billions of dollars higher than it was a decade ago. That’s exactly opposite the trend we would see if gas utilities were winding down their infrastructure in line with climate science.

So, in addition to drawing a “bright line,” regulators in Cascadia could immediately initiate proceedings to estimate the likely scale of future stranded assets in the region and develop rules and procedures to protect ratepayers. (Some financial mechanisms that could partially protect ratepayers from eating the full cost of stranded assets include “accelerated depreciation” and “securitization.”8

See the Environmental Defense Fund’s discussion of these ideas in its report on stranded gas assets in California.)

Ultimately, fully dealing with the stranded asset challenge may require additional public funding from state legislators, if regulators decide it is neither fair to deny utilities and their shareholders repayment nor just or reasonable to lay the cost on ratepayers.

Scattershot electrification is no longer enough

Cascadia is electrifying. Its gas infrastructure now needs to shrink accordingly. Strategic gas decommissioning and neighborhood electrification are the way of the future and will require new, sometimes untested strategies by regulators and legislators. Early work in California, Colorado, and New York can give Cascadia a running start. Smart first steps would be removing gas utilities’ “obligation to serve,” requiring gas utilities to identify neighborhood electrification and decommissioning projects that can avoid the need for new and replacement gas pipes, galvanizing neighborhood electrification through new and more targeted financing mechanisms, and shielding ratepayers from ballooning stranded assets.

Above all, Cascadian leaders will need to follow principles of accelerating action to combat climate change through potentially new and innovative policies and regulations, as well as minimizing burdens on low-income households.

Building and incentivizing clean appliances and infrastructure for individual homes—Cascadia’s approach to date—is necessary but not sufficient to meet today’s climate challenge. It’s time now for a step-change to electrify entire neighborhoods and start the even harder work of untangling communities from dirty infrastructure.

Estimated miles still to be replaced | Estimated pipe replacement cost |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oregon | Washington | Idaho | Total | Oregon | Washington | Idaho | Total | |

| Avista | 145 | 177 | 63 | 385 | $173,318,455 | $128,598,534 | $41,635,539 | $343,552,528 |

| PSE | – | 228 | – | 228 | – | $588,400,000 | – | $588,400,000 |

| NW Natural | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Cascade Natural | 75 | 107 | – | 181 | $86,310,686 | $126,341,012 | – | $212,651,698 |

| Intermountain Gas | – | – | 565 | 565 | – | – | $149,160,000 | $149,160,000 |

| Total | 219 | 511 | 628 | 1359 miles | $259,629,141 | $843,339,546 | $190,795,539 | $1,293,764,226 |

Sources: Pipeline Replacement Program (PRP) documents filed with the Oregon PUC and Washington UTC by Avista, PSE, and Cascade Natural; Case No. INT-G-17-07 filed with the Idaho PUC by Intermountain Gas.

Methodology: PSE and Avista provide information on the miles they have already replaced in Oregon and Washington as part of the PRP and totals that they plan to replace. Sightline found the difference to estimate the number of miles still to be replaced and used average historical costs per mile to estimate remaining costs. Avista also provides total priority pipes to be replaced across Idaho, Oregon, and Washington; Sightline calculated Idaho figures by subtracting the Oregon and Washington totals from the total for all three states. Cascade does not provide information on total miles it plans to replace, so Sightline estimated the remaining miles to be replaced and costs per mile based on the company’s historical averages. Intermountain Gas figures are based on a 2018 filing the company made to the Idaho PUC stating that it had 580 miles of pipes to replace and was replacing them at a rate of 5 miles per year.

Comments are closed.