Takeaways

Gov. Tina Kotek set a very public goal of producing 36,000 homes per year, but each below-market home requires an average of $225,000 in state subsidy. Also, many people who make too much to qualify for those homes still struggle to pay for housing.

A state payment averaging $25,000 per unit could greatly boost production of mid-price homes, especially in less wealthy parts of Oregon.

Making that payment an interest-free loan, paid back in lieu of some property taxes, could further cut the cost per mid-price home to just $10,000

Find audio versions of Sightline articles on any of your favorite podcast platforms, including Spotify, Google, and Apple.

Oregon’s housing catastrophe comes down to this: Alongside every home built in the state since the Great Recession is the ghost of another home that never was.

Cottages that might have slipped into backyards if they’d been able to cover the sewer connection fee. Apartment buildings that might have filled up with nursing assistants and preschool teachers if they’d qualified for a slightly larger loan. Would-be projects across the state that, for one of a thousand reasons, came up a little short on cash and never left the drawing board.

Economists calculate that it’s added up to the country’s fourth-worst housing shortage. When there aren’t enough new homes, bidding wars begin for the old ones. Since 2010, untold thousands of these price battles across Oregon have driven up home prices more than 60 percent.

A grizzled squad of the state’s housing nerds says they have a “big idea” that could help end these bidding wars by bringing these ghost homes to life, especially in smaller cities where low wages and decrepit infrastructure keep much of anything from being built. They calculate that a $300 million investment could produce 12,000 mid-price homes around the state within several years.

That’d be enough to meet several years’ worth of the state’s new production goal for that price category.

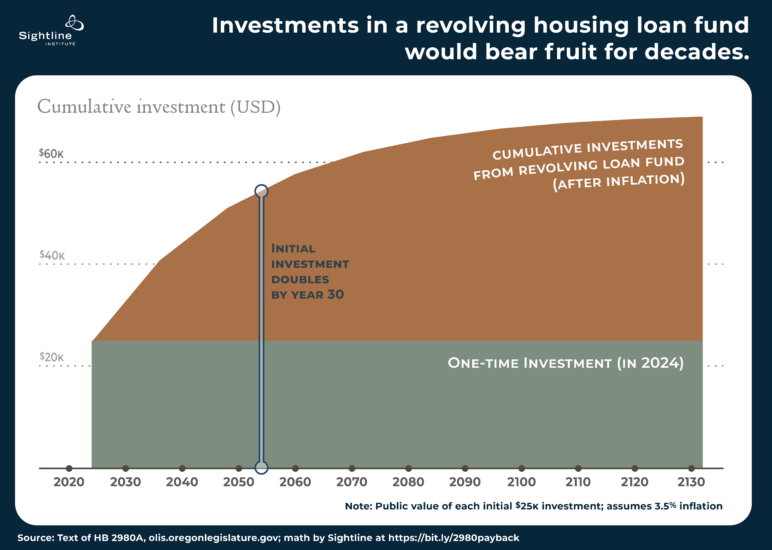

Then, like blueberry bushes, the seeds planted would bear fiscal fruit year after year. Even without further funding, a revolving housing loan fund seeded by a one-time state investment would produce thousands more homes over the decades to come, bringing the total public cost to $10,000 per home created.

The catch is that it’d cost money up front. But the concept’s backers say that if Gov. Kotek hopes to come anywhere close to her high-profile goal of nearly doubling housing production, there’s no more cost-efficient way to push up the numbers.

The idea for making more of Oregon’s ghost homes exist was captured this year in House Bill 2980. On Friday, the Portland Business Journal reported that that bill appears dead for this year; its backers aim to keep developing it and introduce it again.

Its concept is simple. The money comes from the future.

Happy homes and ghost homes

In a state with too few happy stories about housing, Mieko Frederick’s sidewalk-level apartment in Newberg, Oregon, might be home to one of the happiest.

Sitting at the little wooden table outside the door to Unit 103, a few blocks from downtown, Frederick cheerfully counted the ways she loves her new place, built in 2020.

“The grocery store is there, the library is there,” said Frederick, 83, gesturing this way and that from the makeshift patio she set up after moving into the three-story building a year-and-a-half ago. “I can walk and go everywhere.”

Then there are the stories like the one about the 8th Avenue Garden Cottages.

That was the name Dirk Knudsen gave his plan to add eight 250-square-foot freestanding homes to an oversized backyard just southeast of downtown Hillsboro, a booming tech hub north of Newberg. Within three blocks were a hospital, a university campus, a grocery store, and a light rail stop. “We were looking for students, lower-income people in the service sector, and also seniors looking to move down out of their existing homes,” Knudsen recalled.

But between construction costs and the $34,000 per new home that Hillsboro charges to finance new roads, pipes, and parks, Knudsen calculated that he couldn’t bring the cottages to market for less than $260,000 each—and he estimated that nobody would be willing to pay that much to live in one. So he pulled the plug. Today, the backyard is still sitting mostly empty, and the eight households that might have lived there are instead competing for housing with everyone else in Hillsboro.

“We can’t solve the affordable crisis if we don’t solve the housing shortage”

The difference between Frederick’s success story and Knudsen’s ghost story—about $25,000 per home—isn’t much compared to the $400,000 cost of developing most mid-price homes in Oregon.

“It’s actually really common to have small feasibility gaps, especially on middle housing types and types that are more likely to be affordable to people on middle incomes,” said Lorelei Juntunen, the president of Oregon-based consulting firm ECONorthwest. “That is a reason why we don’t see a lot of those housing types even in zones where they’re allowed.”

Bill Van Vliet, executive director of the Network for Oregon Affordable Housing, attributes it to the high costs of new infrastructure that new homes need. Many local governments are just too poor to pay for that infrastructure up front, he said.

“Entire counties issue, like, ten building permits a year,” he said. “It’s all the roads and sewers and sewer treatment plants and water treatment plants needed to accommodate growth.”

Van Vliet said the state can’t solve its shortage with below-market-rate homes alone.

“We’re appropriately pouring increasingly big amounts of money into it, but we’re not making enough progress towards 36,000 units,” said Van Vliet, who estimates that his organization has financed about 14,000 below-market affordable homes around the state since its founding in 1990. “We can’t solve the affordable crisis if we don’t solve the housing shortage at the same time. Because it’s all connected.”

Van Vliet, Juntunen, and Greg Wolf, a former executive with the Association of Oregon Counties now running the think tank iSector, were among the crew who hammered out HB 2980. It was sponsored by Rep. Pam Marsh (D-Ashland) and Sen. Dick Anderson (R-Lincoln City).

“We call this our big idea bill,” Marsh told Oregon’s House Housing committee earlier this year. Last month, that committee sent it on to the state’s budget committee with an 8-2 vote of approval.

“It’s a brilliant, audacious idea,” said the Housing committee’s Democratic co-chair, Rep. Mark Gamba of Milwaukie.

How a revolving housing loan fund would work, in short

Here is what a bill along the lines of HB 2980 would do.

It would let the State of Oregon send money to people building relatively lower-priced homes around the state that can’t quite make their numbers work. Then, over the next ten years, the state would recoup its interest-free loan out of a payment in lieu of taxes.

In other words, the project borrows tax money—taxes that its owner would have had to pay anyway—from its own future.

Ten or fewer years after the initial payment, three things would be different:

- The local property tax base would be bigger than it otherwise would have been, an ongoing boost to local city, county, and parks budgets as well as the state’s school taxes. “You create a pipeline of future revenue growth for the city that wouldn’t be there anyway,” says Van Vliet.

- Oregon would have more relatively inexpensive homes than it otherwise would have.

- The money would have flowed back to the state loan fund, ready to be loaned out again.

“Whenever the loan is repaid, it goes away and everybody gets their money back,” said Juntunen, a lead consultant to Oregon’s land use and affordable housing agencies in their efforts to accelerate homebuilding.

How a revolving housing loan fund would work, in detail

If you want to understand the idea more fully, it can help to walk through the numbers for a particular apartment building.

Let’s use Frederick’s—a three-story apartment building near downtown Newberg that went up in 2020. We’ll imagine that it had been on the cusp of not being built.

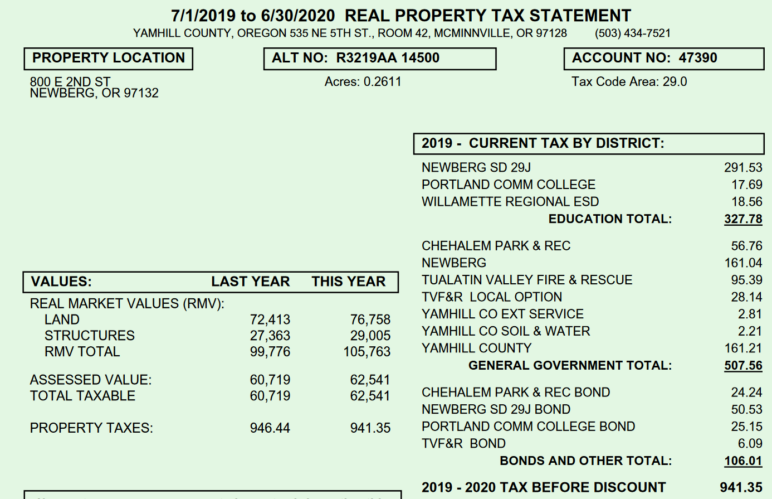

Here is the property tax bill that Yamhill County sent the owner of 800 E. Second St. in 2019, back when it was still a fenced-in storage lot:

Before Frederick’s future home was built, the land’s owner was paying a total of $941 per year in property taxes. That $941 was then divvied up among ten government budgets and to pay back four past loans, or bonds, taken out by the government. (The single biggest line item, though associated with Newberg School District, didn’t actually go directly to the district; instead it went, as everywhere in the state, to Oregon’s general fund. That fund in turn pays local school districts on a per-pupil basis regardless of local property values, a reallocation intended to prevent enclaves richer than Newberg from having out-of-proportion school funding.)

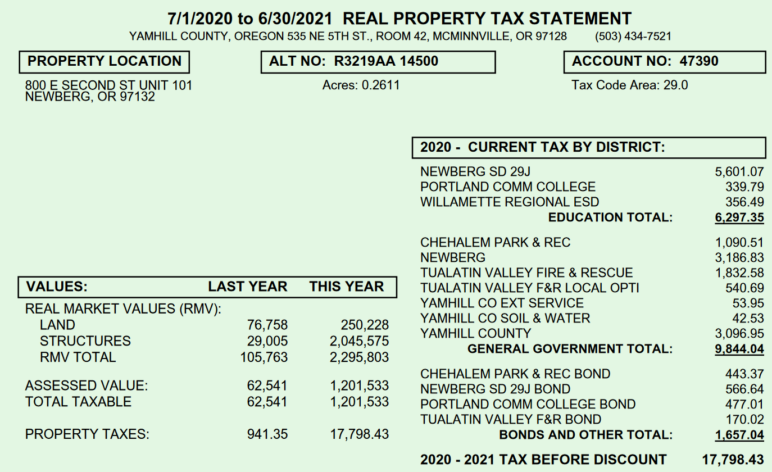

Now let’s look at the same property’s tax bill in 2020, after the apartment went up:

What had been a nearly vacant quarter-acre lot was suddenly gushing cash. The almost $17,000 per year in additional taxes came, ultimately, from a share of the rents paid by everyone living in the new building. (Frederick said she pays $950 a month.)

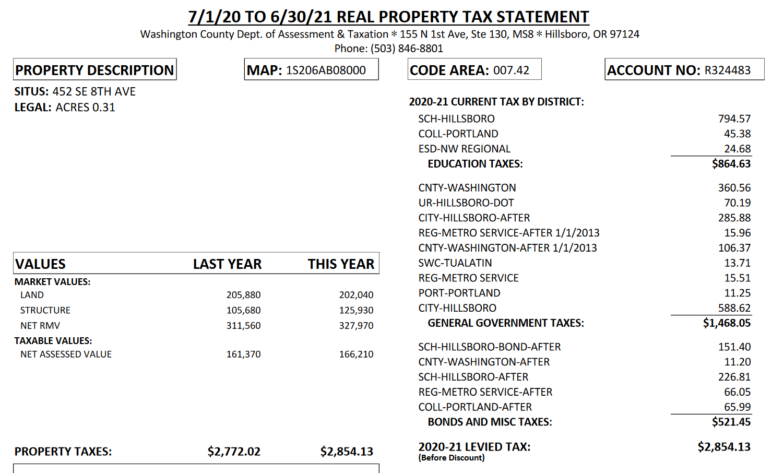

Frederick’s building, of course, would have had no cash to gush if it had never been built. Here’s the 2020 tax bill for the modest house with the big backyard on 8th Avenue in Hillsboro where Knudsen had hoped to add eight backyard cottages:

Unless something changes, 452 SE 8th Avenue is likely to send in the same measly tax bill for many years to come.

A revolving housing loan fund would be one way to change things for projects like Knudsen’s cottages in Hillsboro. If it were in place, someone like Knudsen trying to develop 452 SE 8th could go through these steps:

- Demonstrate, by filing a business plan sharing costs and revenues of a potential building, that a multifamily project on the site couldn’t work without a little more cash up front.

- Commit to offer the new homes at prices affordable to low- or middle-income residents of the county.

- Meet Hillsboro’s locally defined rules for qualifying projects, written in advance and used on a first-come, first-served basis.

If the building met those conditions, then HB 2980 would authorize the State of Oregon to cut a check for something like $25,000 per home—no more than could be paid back in ten years of property taxes. That money would go to the city, then on to the developer, with the developer taking on the risk if something goes wrong. Buoyed by that cash, the project would move forward.

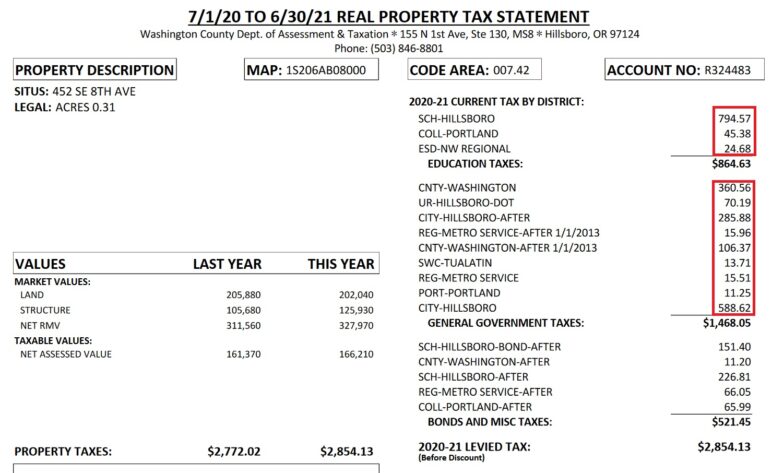

Then, over the next ten years, the line items circled here would become much larger, and most of them (the amount attributable to the new buildings) would flow temporarily back to the state:

Because of Oregon’s per-pupil system of funding its schools, local school districts’ revenue would actually be unaffected. If the new homes brought new students, the state would continue to cover that cost out of its general fund. Meanwhile, fire districts, bond payments, and local option taxes would also be unaffected.

Cities, counties, park districts, and the state general fund would all have to wait up to ten years to benefit from the new property taxes. But because the whole program would specifically target homes unlikely to have otherwise existed, they wouldn’t actually be forgoing much revenue—and after ten years, all would benefit from the larger tax base.

The program wouldn’t be available to projects receiving some other form of tax abatement, or to projects within a designated urban renewal area, because in those cases the additional property taxes would already have been spoken for.

What’s missing: Cash to help plant the first crop of homes

So, what’s the hold-up? Why didn’t HB 2980 sail easily through Oregon’s 2023 legislative session?

The simple reason is money. Once it starts, a revolving fund would be able to finance itself for decades. But it can’t start without a bunch of cash up front. The bill’s supporters proposed $300 million; Gov. Kotek’s proposed two-year general fund budget is $117 billion.

Kotek’s marquee priority for the next two years is a $1 billion public investment in below-market housing. That’d be enough to build maybe 4,500 homes, about 6 percent of Kotek’s total production target, at an average cost of $225,000 per home.

Van Vliet, the affordable housing lender, thinks Kotek should complement that with an investment in mid-price homes: an average of $25,000 per home in the short term.

“In the first three years, you could deploy $300 million and boost production 12,000 straight away,” Van Vliet said. “And that money would be collected over the next ten years, and as that money came back in you could start reinvesting it again.”

By unlocking those new property taxes, the state’s investment would drop to $12,500 per home within the first 30 years and $10,000 or so over the life of the investment.

Fiscal incentives could give cities a new reason to grow

There’s a valid case against concepts like HB 2980. It’s that tax dollars are too precious to subsidize market-rate housing and should be reserved for the people who most need help. If the government wants more market-rate homes to exist, even modest multifamily ones, it should focus on reducing regulatory costs rather than further subsidizing the demand for buildable land.

This is a totally fair perspective. Here are five reasons why a revolving housing loan fund might be a good idea anyway:

1. Each public $1 could bring in more than $20 in private money. A $25,000 public loan can turn the ghost of a home into bricks and sticks, of which the other $375,000 or so would come from investors elsewhere, often outside the state. The property tax flowing back to the state for further loans would more than double that again.

2. The program could become an incentive for cities that upzone. This year, Oregon allowed its land use agency to intervene when cities fell too far behind state housing growth targets. One downside: it’s set up to give state attention only to failing cities. Is that unfair to cities that are doing everything they can? By giving cities access to this program as long as they have recently demonstrated that they’ve removed any local housing barriers, Oregon would be giving itself a fairly cheap way to reward good behavior.

3. There are many regulations that Oregon simply isn’t going to remove. Oregon can’t ignore the Americans with Disabilities Act and probably wouldn’t if it could. Oregon isn’t going to end the building codes that have vastly improved the quality and safety of new construction but didn’t exist when most of its buildings were constructed. Oregon can’t ignore the federal Clean Water Act’s standards for stormwater or drinking water, or the worker safety rules and processes that have probably driven up construction costs.

In Cascadia, bipartisan coalitions can agree on the benefits of re-legalizing apartments, fourplexes, and backyard cottages. But the state imposes lots of other regulatory costs, often for good reasons, that disproportionately block housing in parts of Oregon with less wealth and lower wages. It makes sense for the state to, essentially, fund some of the government’s many unfunded mandates.

4. Cities would have another fiscal reason to prioritize growth, especially of less expensive housing. German cities allow more housing growth—and as a result, enjoy relatively lower home prices—than their peers. It’s likely that part of the reason is that Germany transfers money to cities based on their population. That rewards competition among cities to attract more people—unlike in the United States, where tax systems generally give cities an incentive to attract richer people. A loan fund like HB 2980 would make Oregon a little more like Germany.

5. It’s a perfect candidate for occasional state investment. Most government programs work best with consistent funding; it’s a waste to build a nice new library and then shut it down when you’re short on cash. But a revolving housing loan fund is different. For example, it would be perfectly fine if such a fund got cash infusions only in the years when Oregon collects a bumper crop of capital gains taxes.

Beyond these policy arguments, some backers of a program like this say they see a blunter political argument for something along the lines of HB 2980. Oregon’s new governor has said, over and over, that she wants to approximately double housing production. If housing production doesn’t significantly increase in the next few years, Gov. Kotek’s future opponents will find it easy to call her policies unsuccessful.

Wolf, from the iSector think tank, said he doesn’t see how Kotek can possibly come anywhere close to her goals for additional market-rate housing without dedicating some cash to the problem in a relatively cost-efficient way.

“How else you gonna get there?” he asked. “You don’t have a lot of options for how to do it.”