Takeaways

Parking mandates are a binding constraint on most housing.

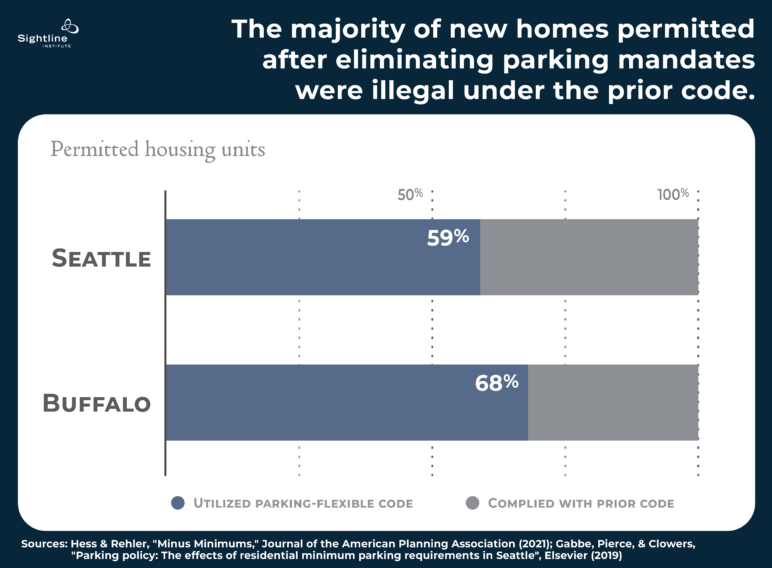

Sixty to seventy percent of new homes permitted in Seattle and Buffalo used flexibility from recent parking reforms to be built.

Find audio versions of Sightline articles on any of your favorite podcast platforms, including Spotify, Google, and Apple.

What comes after repealing parking mandates? Lots of newly legal homes. Studies from two cities observed that in the years following reform, 60 to 70 percent of new homes would previously have been illegal to build.

The new data add to the heap of evidence that parking mandates—local rules that ban new homes and businesses unless they have a pre-determined number of off-street parking spaces—are a binding constraint on housing construction. While only a few buildings opted out of providing parking entirely, most new homes in the studies ultimately benefited from the increased flexibility.

“It isn’t surprising,” said researcher C. J. Gabbe, who authored one of the studies. According to Gabbe, homebuilders have been saying for a long time that demand for off-street parking was lower than what zoning rules required.

The results suggest that across jurisdictions, the majority of potential future homes are being held back, in part, by parking mandates. Based on little to no data, these requirements limit the number of homes that can be built and increase costs for the ones that are, contributing to a housing shortage that has been decades in the making.

“Cities of all types stand to benefit from undoing constraining parking policies of the past,” researchers from Buffalo wrote in their findings. In many cities, though, these new homes remain illegal to build.

Two different cities: Seattle vs. Buffalo

It’s hard to imagine two housing markets more different than Buffalo, New York, and Seattle, Washington. Seventy years of depopulation and disinvestment have left Buffalo with the oldest housing stock in the United States, with most homes pre-dating World War II. Here, housing affordability hinges as much on the high rate of poverty as a shortage of housing. Reusing derelict historic buildings and vacant lots was a primary goal of Buffalo’s zoning code overhaul in 2017, which eliminated parking mandates citywide.

Seattle, by contrast, has never been bigger. Since 2010, the population has increased 21 percent. Despite a surge in homebuilding (one in every three homes was built in the past twenty years), population growth continues to outpace construction, creating intense competition and escalating prices. Partway through this building boom, in 2012, the city reduced or eliminated parking requirements in urban centers and near frequent transit stations.

Both of these cities’ policy changes provided a natural experiment for measuring the effects of parking policy. Researchers in Buffalo collected information on 36 major developments that went through permitting in the two years after its so-called Green Code was adopted. In Seattle, a different team of researchers collected data on 868 new multifamily buildings permitted from 2012 to 2017, accounting for over 60,000 new homes.

Sightline asked both research teams to look through their numbers to see how many homes were in buildings that would have been illegal before the reforms. Both datasets yielded a strikingly similar answer: more than half of new homes.

Lifting parking mandates supported already growing construction rates

The timing of Seattle’s parking reform coincided with an increase in multifamily construction nationally, as the United States recovered from the late aughts’ Great Recession. Similarly, at the time when Buffalo eliminated parking minimums in 2017, people were already talking about Buffalo’s renaissance. New census data confirmed the city is growing again for the first time in 70 years and seeing a record amount of new investment.

“It’s impossible, really, to tie a specific code change to changes in the market,” explained Brennan Staley, a strategic advisor for Seattle’s Office of Planning and Community Development. Other local regulations, housing prices, and international finance markets all play a part in the real estate market. Michael Hubner, who works on long range planning in Seattle, agreed: “It’s very difficult to point to a causal relationship.”

What is clear to Hubner is that the market chose to use the flexibility the city began offering. Not just on the margins, but by a lot. During the first five years after Seattle’s reform, a total of 35,388 new homes in Seattle ended up benefiting from the freedom to not build excess parking. Today, those homes account for 9.4 percent of the city’s entire housing stock.

Staley pointed out other benefits of the flexible code. “It’s not just the supply of those units that may be increased, but also that there are cheaper units because they didn’t have parking,” he said. One parking space can add over $200 to monthly rents. Even when landlords charge for parking separately, they can’t recoup those expenses and so end up spreading the cost to everyone. Seattle researchers estimated that at $30,000 per parking space, builders collectively saved $537 million in expenses that would have been passed on to future tenants.

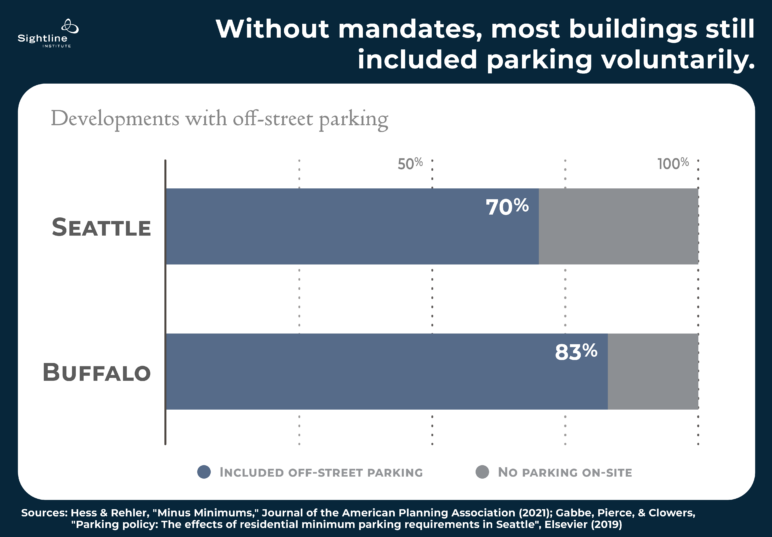

Builders used the new flexibility on parking, while often still providing some

In both cities, the majority of new buildings still included off-street parking voluntarily. Most people own cars, after all. In Seattle, 70 percent of all new buildings continued to provide off-street parking for residents. Buffalo’s ratio was even higher, at 83 percent of major building projects.

But even those numbers overstate the number of buildings with no parking at all, because it doesn’t account for parking on an adjacent property. The Pardee building in Buffalo is one of six housing projects that was categorized as having no parking spaces. But from the street, the passerby would have no idea that the parking lot and the building are technically on separate parcels of land.

Other previously illegal housing developments in Buffalo included a former gas station that transformed into 32 new affordable homes with a bridal shop and gym on the ground floor. On the other side of town, an empty parking lot grew up into a historic-styled main street with ground floor commercial space and 70 new market-rate homes. Both of these buildings included on-site parking, but at lower ratios than what the city had required.

Buffalo, like many other cities, let builders request special permission to deviate from city-determined parking ratios. In the six-month period before the zoning reform, one in three new homes in Buffalo were permitted through that variance process. Once allowed by right, that ratio flipped, with two in every three homes opting to use the new code’s flexibility.

All in all, the market only ended up building 20 percent fewer parking spaces than the previous code had required.

In Seattle, whose reforms were concentrated in the most urban parts of the city, new buildings provided 40 percent less parking than would have been required before the reform. While that sounds like a dramatic drop, the change merely right-sized parking to match existing demand. In fact, it was exactly in line with a separate 2012 study that had observed 40 percent of the parking spaces in King County, where Seattle is located, never get used.

The 2020 study of Seattle also found reason to believe that parking flexibility would be useful in other parts of town, too. Forty-three percent of buildings in Seattle still subject to parking mandates built the minimum number of spaces required, suggesting that these projects might have opted to build more homes per parking space if allowed. That also suggests that an unknown number of homes would exist today if not for the parking mandates still in place.

Lessons for other cities

For most cities, the chilling effects of parking mandates remain largely invisible. Few builders end up taking on the risk and expense of requesting a variance from zoning codes. But thanks to these vanguard cities, the significance of parking reform is finally coming to light.

Far from affecting just a handful of buildings, these studies suggest that a wide array of housing projects would use flexibility around parking minimums if given the opportunity. For cities and states searching for solutions to their own housing shortages, eliminating parking mandates is a simple action that seems likely to help create a lot of new homes.