Takeaways

Cascadia’s gas utilities are betting big on green hydrogen to try and stay in business as the region rapidly transitions off of gas.

But hydrogen is only well-suited for industrial customers, who make up a tiny fraction of gas utilities’ revenue base today. Selling hydrogen to industry cannot make up the revenue utilities will lose from millions of residential and commercial customers switching to electricity.

Utilities would be wise to start looking for more realistic carbon-free lifelines.

Find audio versions of Sightline articles on any of your favorite podcast platforms, including Spotify, Google, and Apple.

Cascadia’s gas utilities know their prospects are rapidly dimming. Decarbonization, now official state and provincial policy in much of the region, is an existential threat to businesses chartered by law to distribute carbon-based fuels. The companies are hoping hydrogen will save them, forestalling bankruptcy as the region leaves fossil fuels behind. NW Natural, Puget Sound Energy (PSE), Cascade Natural Gas, Avista, and FortisBC, the region’s biggest gas utilities, are all developing plans for pumping green hydrogen1 through their pipes. NW Natural plans to produce green hydrogen that it will blend with natural gas and deliver to around 2,400 customers in Eugene, Oregon. PSE has budgeted $6.3 million through 2026 for pipeline modernization for “alternative fuels,” including hydrogen. And FortisBC plans to invest nearly Can$5 million annually to pursue low-carbon fuels like hydrogen.

Policymakers throughout Cascadia have, perhaps unwittingly, dangled the hydrogen lifeline in front of the gas industry, passing laws that allow utilities to recoup the costs of green hydrogen investments. Oregon and Washington passed policies in 2019 encouraging gas utilities to procure and invest in hydrogen on behalf of their customers. That same year, under British Columbia’s Clean Energy Act, BC regulators added hydrogen to a list of prescribed undertakings for gas utilities to lower greenhouse gas emissions.

But hydrogen is unlikely to save gas utilities from their impending irrelevance. Future hydrogen customers are few and far between, and the competitive hydrogen market will leave currently regulated monopoly utilities in unfamiliar waters. In this context, green hydrogen looks more like a leaky raft than the sturdy rescue boat gas utilities make it out to be.

Tomorrow’s few industrial hydrogen customers won’t be enough to sustain gas utilities

Green hydrogen’s best role in decarbonization is to clean up a handful of industrial sectors, like steelmaking, international shipping, and long-haul aviation, that do not have suitable alternatives. Hydrogen makes little sense for decarbonizing homes and businesses. Electrification is a much more efficient, cheaper, and safer option, and one that state, local, and federal policies increasingly incentivize.

But if utilities focus just on selling hydrogen to industrial customers, their balance sheets will show a big hole. That’s because under the eccentricities of utility regulation, utilities profit by expanding their vast web of gas pipelines, not by the volume of gas they sell. Even if utilities can make up the lost volume of gas from residential and commercial customers with a few large industrial customers, they won’t be able to earn the same profit from the much smaller pipeline footprint these new customers will need. Today, NW Natural’s industrial gas consumers, for example, make up 41 percent of the company’s gas volume sold and just 7 percent of profits, while its residential customers make up 38 percent of gas volume sold and 65 percent of profits.

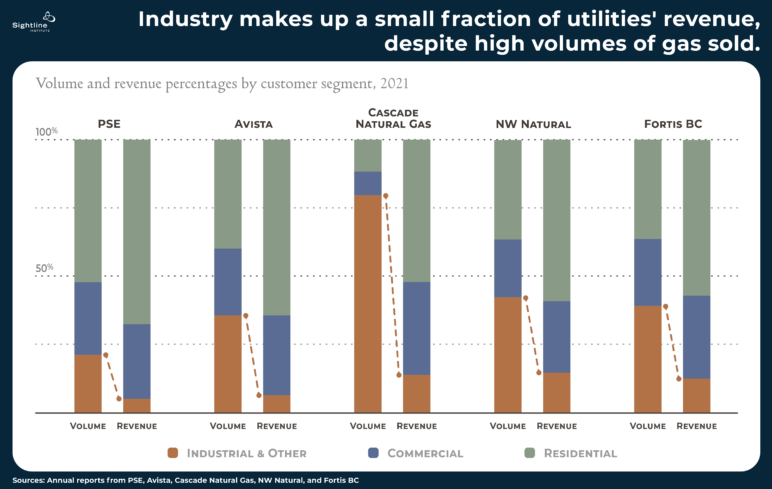

Although Northwest utilities don’t all publish data on the profit breakdowns by customer segment, the chart below shows the next best thing: the customer breakdowns by revenue and volume of gas sold by utility. For all the companies, the volume of gas sold to industrial customers far exceeds the revenues earned from them. The opposite is true for residential and commercial customers: utilities earn more of their revenue from this group relative to the share of gas sold to them because of the investments in the vast web of pipelines required to serve millions of smaller customers.

Thanks to Michael Sweazey for supporting a sustainable Cascadia.

Our work is made possible by the generosity of people like you.

To be fair, gas utilities’ current customer list doesn’t include all potential future hydrogen customers. For example, industries that produce their own hydrogen from natural gas today, like fertilizer manufacturers, could start to source from gas utilities, as could long-haul transportation industries that need to transition off of petroleum products. But today less than 1 percent of Cascadia’s gas consumers are in the industrial sector, including pulp and paper company Georgia-Pacific and aerospace giant Boeing.2 Even if gas utilities are able to secure a handful of big new hydrogen customers, these customers will hardly need the level of infrastructure investments to reach them that today’s millions of homes and businesses that burn gas do.

Making matters worse for gas utilities, as more and more residential and commercial customers disconnect from the gas system, utilities will be left with thousands of miles of unnecessary pipelines. Gas utilities own over 100,000 miles of pipelines snaking under neighborhoods and downtown business districts throughout Oregon, Washington, and British Columbia.3 Utilities offer this extensive pipeline footprint for why they are well-suited to sell hydrogen. But maintaining these pipelines with fewer customers will eat further into utilities’ profit margins, since regulators are unlikely to dramatically raise rates on the remaining gas customers enough to fully cover utilities’ rising costs. In that context, utilities’ vast network of pipelines looks far more like a liability than an asset in a decarbonized world.

Natural gas utilities will need to compete for the hydrogen delivery market

On top of the income gap that residential and commercial gas customer attrition poses to gas utilities, wading into the hydrogen business won’t be straightforward for these regulated entities. Unlike today, when they enjoy monopoly status, they’ll have to compete. Already, hydrogen consumers, like oil refineries and fertilizer manufacturers that use fossil fuel-based hydrogen, have options for obtaining the gas: they can receive it via truck or pipelines from private companies like Air Liquide or produce it on-site using steam methane reformers fed by natural gas pipelines, as is done at the BP Cherry Point refinery near Bellingham.

Plus, as green hydrogen replaces fossil fuel-based hydrogen in the market, consumers may opt to produce hydrogen themselves from electricity instead of natural gas, forgoing trucks and pipelines altogether. For example, Seattle City Light, Pacific Northwest National Lab, and Sandia National Lab are studying producing green hydrogen at the Port of Seattle. The Port would install an electrolyzer4 on site and use renewable electricity to make green hydrogen from water. The study will examine the viability of using this hydrogen to power heavy equipment like forklifts, drayage trucks, and cranes, and to fuel larger vessels like ferries, commercial fishing vessels, and tugboats. Outcomes of the study could pave the way to powering larger vessels like freighters and cruise ships with hydrogen.

Natural gas utilities may end up controlling some of the hydrogen pipelines, but they will need to participate in an unfamiliar competitive market in which the hydrogen trucking industry, electric utilities, and other hydrogen pipeline owners all jockey for a piece of the hydrogen distribution business.

Gas utilities would be wise to search for a different lifeline

Gas utilities’ vision, to forestall the demise of the industry by swapping low-carbon gases like green hydrogen for natural gas, fails to account for the likelihood that only a tiny sliver of their customer base is likely to use hydrogen and that those that do will have options for delivery in a competitive market. Hydrogen simply cannot sustain business-as-usual for gas utilities.

Instead, the region’s gas utilities would be wise to start searching for alternative pursuits to transition their businesses away from fossil fuels and hydrocarbons. One such alternative, as the Washington State Energy Strategy suggests, could include providing low-carbon thermal energy to heat and cool homes and businesses, a topic Sightline will turn to in a future article.

Comments are closed.