Takeaways

Like cities across America, Anchorage tends to overbuild parking.

Returning control over parking decisions to property owners and businesses can help to right-size parking to each site’s unique needs.

Turnagain Brewing and Anchorage eBikes are just a couple of examples of Anchorage businesses burdened or altogether blocked by parking requirements.

Find audio versions of Sightline articles on any of your favorite podcast platforms, including Spotify, Google, and Apple.

Anchorage needs parking. The city was built around cars and so almost everyone uses them, whether they want to or not. Naturally we need a place to put them. But who should have the power to decide how much parking Anchorage’s homes and businesses need?

It’s a question that’s come up in cities and states across the US. City zoning codes tend to dictate how many parking spaces, say, a retailer or homebuilder needs to pave. The problem is that cities frequently overestimate how much parking a site actually needs. And so, city after city, and the states of California and Oregon, have decided to return that power to the people on the ground who have a much clearer idea of parking needs for the properties they own, projects they’re developing, or businesses they run.

A study conducted by the city in the late 2000s found a chronic oversupply of parking on multifamily and commercial properties across Anchorage, with 1 in 4 city-mandated parking spaces sitting empty at peak periods…

Anchorage could do the same. Like other cities across America, Anchorage has erred on building more parking than necessary. In every neighborhood except downtown, Anchorage code has highly specific (but not scientific) rules dictating the minimum number of parking spots required for over 100 business and housing types, from dry cleaners to bingo parlors to triplexes.

A study conducted by the city in the late 2000s found a chronic oversupply of parking on multifamily and commercial properties across Anchorage, with 1 in 4 city-mandated parking spaces sitting empty at peak periods. Of the 35 sites listed, 31 of them never used all the parking required under the land use code, commonly referred to as “Title 21.”

…of the 35 sites listed, 31 of them never used all the parking required under the land use code, commonly referred to as “Title 21.”

“Well,” you might think, “that seems fine. Hunting for parking is painful. The more parking the better!”

Sure, an undersupply of parking spaces isn’t fun when you’re circling a lot. But an oversupply has insidious and less obvious downsides. Forcing businesses to provide more parking than they need costs them (and, by extension, you) thousands of dollars per stall. That’s why even Walmart is asking cities for permission to build less parking as more of its sales go online. And requiring extra spots that rarely, if ever, get used makes new housing much harder to design, more expensive to build, and pricier to rent or own. In the worst cases, government mandates to build excess parking snuff out new growth completely.

In Midtown, a local dentist finds parking rules bite

Take the case of Anchorage dentist Guy Burk. In 2020, Burk received a letter from the city warning him he’d be fined $300 per day for lack of parking at his Midtown office. Burk was stunned. He has more than 50 parking spaces to accommodate the 20 or so employees and patients who are in his office at peak times. In fact, he has so much parking that he lets visitors to the neighboring strip mall use the extra spots.

“Parking capacity is a problem that should be on the business owners to solve…. Why is the city getting involved at all?” –Guy Burk, dentist and owner of Anchorage Midtown Dental Center

“Parking capacity is a problem that should be on the business owners to solve,” Burk said. “If there’s not enough parking, my patients will say, ‘There’s not enough, and I’m going to go to another dental office.’ Why is the city getting involved at all?”

The city asked Burk to submit a parking agreement showing that Burk and the owners of the lot he leases would provide parking in perpetuity.

“Nobody’s going to do that,” Burk said. “No one’s going to lock up their land like that.” To avoid the fine, Burk bought three vacant parcels another block away, in case the city made him build more parking. He estimates that paving the parcels would cost nearly $200,000. In the meantime, he’s been working with the city on a possible temporary shared parking agreement and a parking use study.

“They’re taking away my ability to grow companies that the community needs.”

Burk would prefer to put his money and time toward two businesses—a dental milling and printing center and an industrial ATV retailer—that he’s planning for the building next door. But there again he will need another shared parking agreement, since zoning code requires about five times the number of spots Burk calculates he’ll need. Because of the parking issue, he’s put the renovation on hold.

In Burk’s view, minimum parking requirements are the biggest problem in Anchorage. “They’re taking away my ability to grow companies that the community needs,” he said.

Anchorage Assembly considering changes to parking rules. But are they enough?

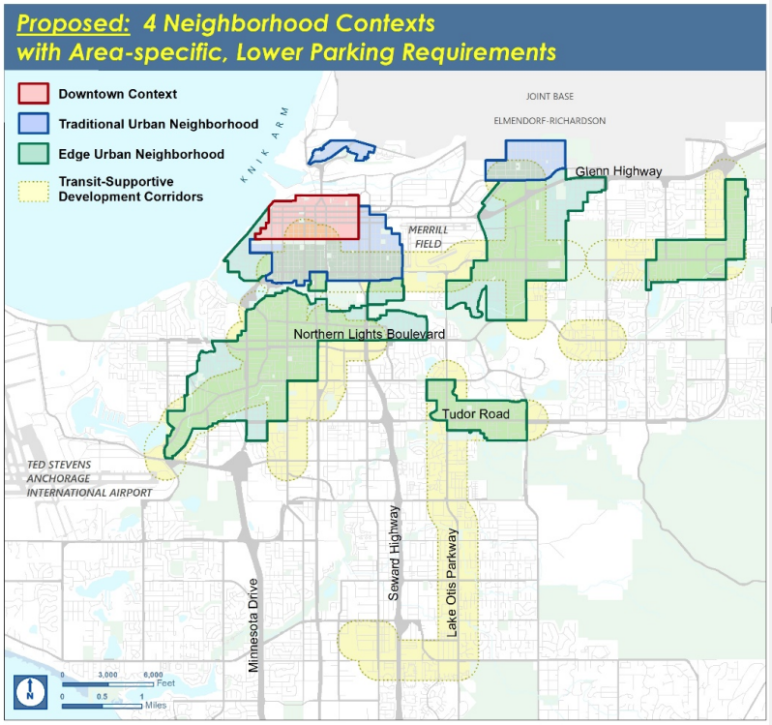

The Anchorage Assembly is considering updates to Title 21 that would reduce parking requirements in several neighborhoods, including Spenard, Bootlegger’s Cove, and Fairview. The draft ordinance also aims to smooth out the process of asking the city for permission to build less parking than current rules mandate; in other words, to avoid overbuilding parking on individual properties across the municipality.

City planners, hoping to address the many downsides of excess parking, spent two painstaking years gathering community input and writing the ordinance. They noted the many unnecessary costs of excess parking, which include making housing more complicated and expensive to build; burdening taxpayers; causing heated runoff, heat islands, and other pollution issues; and worsening traffic.

The resulting proposal would still require many hours of work and potentially substantial investment by anyone seeking permission to avoid building too much parking. For example, an applicant could reduce parking by up to 2 percent if they set up a carpool program, or up to 10 percent by building bike parking. And they’d need to follow detailed regulations for carpool programs and bike parking in city code.

Burk’s properties fall just inside a zone that would see a modest easing of parking requirements under the proposal, but he’s not optimistic. “It does me no good,” he said. “Whatever reduction they propose will be far less than what we need. It’s not a solution because it’s still one-size-fits all.”

To more meaningfully trim back Anchorage’s parking oversupply, the mayor, assembly, and other city officials could consider putting more trust in individuals to decide how much parking to provide.

Cities and states are taking government out of parking decisions

From a city’s perspective, giving up the authority to require parking might feel like an invitation to chaos, with droves of irate drivers complaining about a lack of parking. But underbuilding parking is a losing strategy for business owners and landlords, and they continue to build it even when government isn’t making them.

In the many other cities that have returned parking decisions to builders and property owners, there’s still plenty of asphalt being laid for parking. After Buffalo, New York, eliminated parking minimums citywide in 2017, a study of 36 large-scale developments in the two years following found that 86 percent of the new buildings still provided parking. More than half of new projects either built as many or more parking spaces than the old code required.

“Rather than city planners, developers and homebuilders are in the best position to know how much parking should be provided at each site,” wrote scholars Salim Furth and Emily Hamilton in a 2022 housing policy brief for the free-market think tank Mercatus Center, at George Mason University.

Eliminating parking requirements wouldn’t restrict new parking lots from being built or trigger an avalanche of new construction without any parking. In Seattle, 70 percent of new housing developments near transit still built parking after requirements were lifted. Many North American cities, including Minneapolis, Edmonton (Canada), and Houston, have rolled back parking requirements. In July the state of Oregon rolled back its parking mandates, followed by California in September.

And in Anchorage? The city’s downtown hasn’t had parking requirements since the late 1960s. Still, it has a glut of excess parking in its many surface lots, multi-level garages, and on the street. In fact, “destination development” expert Roger Brooks, at the Anchorage Economic Development Corp’s annual luncheon in August, gave a talk on how to attract and retain a workforce to fill thousands of vacant positions across the state. One of his recommendations? Reducing the number of surface parking lots that are “taking up valuable real estate downtown.”

The few housing developments built downtown in recent years all have included ample parking for residents. Block 96 Flats, a complex of several dozen studio and one-bedroom apartments, includes heated garage parking. Spearheaded by developer Sean Debenham, Block 96 will be Anchorage’s first larger-scale market-rate housing downtown in 40 years. Nearly $1.8 million of the $11.6 million development cost (about 15 percent) will go toward parking.

Proposed zones for lower parking mandates exclude many Anchorage properties

“It was a year of stress. If that was not approved, there was no way my business could make money.” –Mary Rosenzweig, Co-owner of Turnagain Brewing

The city offers a process to avoid building excess parking, but it’s not easy. Two years after Turnagain Brewing opened, the city discovered it was six parking spaces short of the minimum. The previous occupants had expanded the space without building additional parking as required under code. City staff didn’t appear to have noticed until the craft brewery applied to participate in the city’s pandemic dining program to prepare food for people in need in exchange for relief funds.

The brewery had no room to build the spots. Co-owner Mary Rosenzweig had to submit a parking study to the city for an exception or be forced to close the upstairs retail space. “It was a year of stress,” Rosenzweig said. “If that was not approved, there was no way my business could make money.”

Rosenzweig spent two weeks monitoring the parking lot to confirm what she already knew: it rarely filled up. And since Anchorage requires breweries to be located in industrial areas, they are the only business open during the evening, and so have little competition for street parking. The brewery is also right off the Campbell Creek Trail, where many people walk and bike.

“There are plenty of times when my parking lot is pretty much empty, and yet we are filled on the inside because so many people are on bikes,” Rosenzweig said. “In my situation, the parking requirement just doesn’t make sense.”

Turnagain Brewing is one of about 100 applicants the city agreed to relieve of parking mandates over a 5-year period. The brewery is one of many businesses located outside the zones that would see parking reductions under the proposed ordinance.

Parking Reduction Agreements in Anchorage, 2016–2020

Parking requirements lock up land and kill innovation

In parking reform discussions, Rustic Goat, the popular West Anchorage restaurant, tends to suck the air out of the room. The restaurant is one of the few examples of mixed-use development in Anchorage and shares a parcel with six townhouse-style apartments. Rustic Goat was supposed to draw most of its customers on foot and by bike from the adjacent neighborhoods of Spenard and Turnagain (a.k.a. “Spenardagain”). But, as with all things new and buzzy here, it attracted diners from across the city after opening in 2014. People started parking on the narrow streets nearby. The neighbors were not happy. Rustic Goat built more parking to fix the undersupply and remains a mainstay on the Anchorage restaurant scene.

The idea that the city should deploy parking requirements to prevent another Rustic Goat has persisted ever since. “For eight-and-a-half years sitting on this commission, the proverbial adage was, ‘Don’t do another Rustic Goat,’” Planning and Zoning Commissioner Greg Strike said in a June hearing.

“These problems are very local and very specific. You use our parking numbers as a requirement for somebody else, they’re going to have way too much parking.” –J. Jay Brooks, developer of Rustic Goat

But parking mandates are the wrong tool for handling site-specific parking issues, and they kill opportunities for other businesses. “These problems are very local and very specific,” said J. Jay Brooks, who developed Rustic Goat. “You use our parking numbers as a requirement for somebody else, they’re going to have way too much parking.”

Fears of creating another parking shortage guarantee that Rustic Goat will continue drawing drivers from outside Spenardagain because those drivers’ own neighborhoods won’t have the opportunity to build their own hyperlocal eateries. Not to mention killing an unknowable number of other innovative housing and commercial projects that could help the city refresh old buildings and underused properties.

Cary Shiflea, the owner of Alaska eBike, had architectural drawings and financing lined up to buy the building the company leases on the northern end of Spenard Road. He planned to add three apartments upstairs and expand the shop below. But building more than two residences triggers a raft of regulations in Anchorage, including 1.25 to 2.5 parking spaces per household depending on the number of bedrooms. Shiflea learned from a consultant that the remodel would likely require him to triple the number of existing parking spaces.

“We looked into nearly everything,” said Shiflea, including digging out space for parking underground, a project far beyond his budget. Even the estimated $25,000 it would cost to navigate the variance process was too risky. “At the time, there was no way anyone was going to let it happen because Rustic Goat had just opened,” said Shiflea. “It blew it for everyone.”

Shiflea plans to move to the Mat-Su Valley in the next few years. Not even a wholesale elimination of parking requirements would persuade him to revisit his plans. “It’s now locked into its state forever,” Shiflea said about the outdated 1957 building. “No one will touch it if they need parking spaces.”

Lifting parking mandates won’t cause dramatic changes right away

The best way to get rid of unused parking is to stop forcing people to build it in the first place.

The best way to get rid of unused parking is to stop forcing people to build it in the first place. Unused parking spots waste land and money. They represent unbuilt homes, unopened and unexpanded businesses, and wildlife habitat that didn’t have to be destroyed. They block the way to a more diverse mix of public transit and human-powered transportation. Bus service, cycling, and walking cannot flourish amid a sea of parking lots.

What could happen to Anchorage if parking mandates went away? At first, probably nothing noticeable. Life would go on. But maybe that long-vacant building you pass every day comes back into use in a year or two. Maybe more starter homes start appearing on the market. Maybe more businesses arrange to share parking. Maybe your neighborhood gets a store or bakery that your kids can get to on their own. Or, if you’re really lucky, maybe a rad new restaurant opens down the block and you can finally stop driving to Rustic Goat.