Takeaways

Inefficient use of land, caused in part by restrictive zoning laws, is constricting Anchorage’s housing supply, making homes more expensive for everybody in an already tough economy.

If you want to build a triplex in Anchorage, you’re subject to the same standards as if you were building a big-box store.

Parking and setback requirements, plus a ban on pairing duplexes with accessory dwellings, can also make three-unit homes harder to build than a much larger one-family mansion.

Find audio versions of Sightline articles on any of your favorite podcast platforms, including Spotify, Google, and Apple.

There’s not much consumer choice in the Anchorage housing market. Single-detached homes, or “one-plexes,” are the norm, even though residents want more options to accommodate their different life stages and budgets. So, some of Alaska’s top architects and builders teamed up with Fairview residents in a neighborhood design contest to imagine a future inspired by historic housing norms, when cities allowed a wider array of homes in American neighborhoods.

In the Fairview design contest, teams proposed plans for a hypothetical triplex on a real-life vacant lot. The entries included:

- a coworking residence for remote workers looking to split housing costs with roommates;

- a duplex-plus-backyard-cottage option perfect for multigenerational families;

- a modern triplex that could work for people who aren’t into paying for a suburban house (not to mention lawncare); and

- underground apartments that might attract avid gardeners and avant-garde urbanites.

Unfortunately, Anchorage city code, as written, makes every one of these designs either impossible or much harder to build than a single-detached house. A thicket of zoning rules, including parking requirements, setbacks, and onerous site preparation for triplexes, ensures that inefficient land use will continue in Anchorage for the foreseeable future. But changes may come soon. The contest helped spur the city to reconsider some of the zoning regulations that impede triplex construction, skew the market, and squash innovation.

A housing refresh on a Fairview lot

Cook Inlet Housing Authority (CIHA, pronounced “see-ha”) stands out among the many groups working to make Anchorage’s housing stock more appealing to a broader group of renters and homebuyers. In 2019 CIHA partnered with the Fairview Community Council to sponsor a triplex design contest—a contest that ended up highlighting the biggest regulatory obstacles to expanding home choices. Local planning officials have since used these insights to move toward modest reforms to parking rules and other parts of the Anchorage land use code.

The contest, dubbed COMP/act, was a community endeavor. (The name is a play on “competition” and the need for “action” that will allow construction of more compact housing styles.) The Rasmuson Foundation provided a grant to run COMP/act and award cash prizes. The Anchorage Museum featured the contest at an event in its SEED Lab. And the Anchorage Economic Development Corporation’s Live.Work.Play. committee helped to promote the contest.

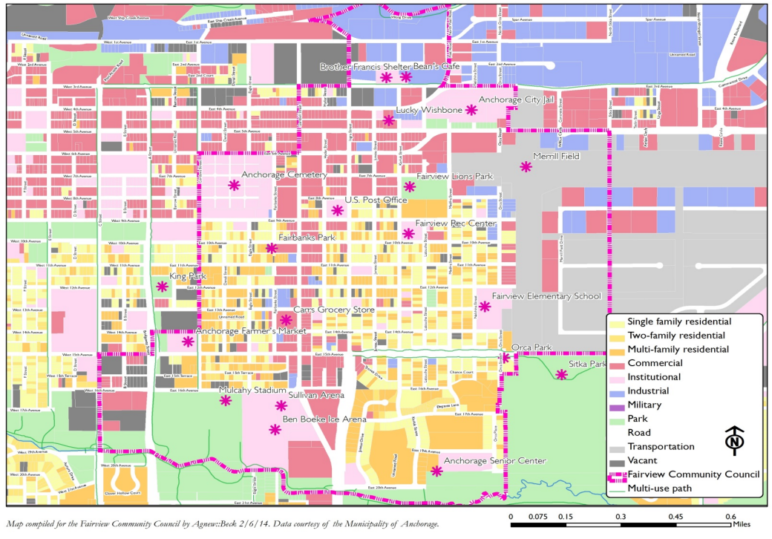

Four teams made the finals. Each consisted of a designer, a builder, and a neighborhood resident, with a vacant property in Fairview serving as the blank slate for their designs. The rectangular, 7,000-square-foot lot at 820 Nelchina Street is covered in vegetation and sits between a blue ranch house and a fourplex. The property is remarkable not for what it is but for what it represents: a way to envision how Anchorage might modernize the city’s housing stock, meet consumer appetites for more price points and housing styles, and use land more efficiently while preserving the intimate scale of the neighborhood.

Historically, Fairview was one of only a few Anchorage neighborhoods where Alaska Natives and Blacks could own land. White neighborhoods, including Turnagain and Rogers Park, put in place racial covenants barring the sale of homes to non-whites. Following the exclusionary tactics used by Berkeley, California, and countless other American cities throughout the twentieth century, Anchorage created socioeconomic walls around desirable neighborhoods through zoning laws that made building more than one unit per lot relatively difficult.

Today, the covenants are illegal, but the zoning laws live on. Rules like lot size and square footage minimums have made the real estate market less affordable over time and helped create the housing shortage we see in Anchorage today. These laws banish more compact and affordable housing types, and the people who might have lived in them, from many Anchorage neighborhoods. Though exclusionary zoning was intended to keep non-whites out of certain neighborhoods, the reality is that people of all racial backgrounds have suffered from the tight housing supply that’s resulted.

Single-unit properties on large lots dominate the Anchorage housing market, driving up costs for anyone looking to buy or rent. Single-detached homes account for 80,274 of occupied housing units in Anchorage, according to the 5-year American Community Survey in 2020. Combined, the six other housing types counted in census data, including duplexes, triplexes, townhomes, and mobile homes, account for the other 58,660 living units.

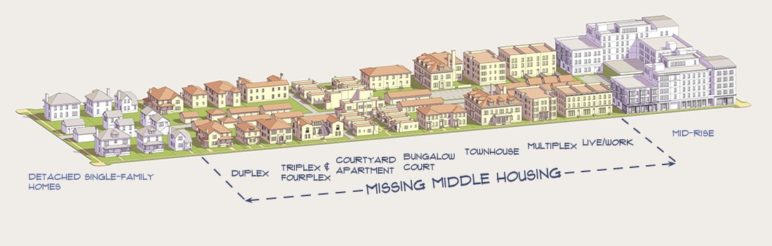

Zoning rules allow multifamily homes across nearly all of Fairview, putting the neighborhood in a better position than many others in Anchorage to build what’s known as “missing middle housing.” These are the duplexes, triplexes, quads, townhouses, and backyard cottages that used to be much more common in the United States before exclusionary zoning spread across cities and towns during the middle decades of the last century. Easing the way toward these more attainable housing types would help Fairview achieve the goals in its 2020 neighborhood land use plan: “Fairview should contain a diversity of housing types to enable citizens from a wide range of economic levels, ethnicities, cultures, and age groups to live within our boundaries.”

More middle housing could also make buying or renting across Anchorage attainable for more households without contributing to urban sprawl. Unlike large apartment buildings, middle housing fits in with the modest scale of Anchorage’s suburban neighborhoods. It also creates more compact neighborhoods that, when combined with smart commercial zoning and good winter sidewalk maintenance, could allow residents to integrate more wallet-friendly transportation options, like walking, biking, and taking People Mover, into their daily lives.

Zoning laws make triplexes hard to build in Anchorage

So, back to the COMP/act design competition: in addition to designing a triplex, teams had to identify the regulations that stood in the way of their projects but weren’t critical to health and safety. A major impediment? The classification of triplexes as commercial buildings. Duplexes and single-detached homes fall under the relatively straightforward “residential” building code. But triplexes are notoriously hard to build in Anchorage because adding a third housing unit pushes the development into the commercial building category, triggering a raft of extra requirements. Three-unit homebuilding projects go through the same regulatory compliance process as a Wal-Mart or a 50-unit apartment complex.

“We weren’t treating it as just a design competition. It was something this team really believes in and wants to see happen.”

If triplexes were easier to build, Anchorage might see more cottage clusters, like the one designed by the team of Fairview resident Erika Ammann, builder Ryan Watterson, and architectural firm Bettisworth North. Their contest entry centered on three independent structures, limited in height to allow for light from the south and west in the later afternoon and evening.

“From a firm standpoint and making Anchorage a better place, someone has to go and stick their neck out. This competition was the opportunity,” said Roy Rountree, a principal at Bettisworth North.

The team proposed two ownership models. The first would allow for each unit and the land beneath it to have different owners. This model would require the formation of a homeowners association to pay for basic maintenance, including the lawn, water and sewer, and snow removal. Alternatively, a single owner could live on the property and rent out the other two units. The cost per unit (pre-pandemic) was $282,238 for each of the two-bedroom units and $169,540 for the one-bedroom.

“We weren’t treating it as just a design competition,” said Leah Boltz, of Bettisworth North. “It was something this team really believes in and wants to see happen.”

The team has been scouring Anchorage for another place to build the project, but hasn’t been able to find the right piece of property in part because of Anchorage’s high regulatory barriers to triplexes.

Under the multifamily building section of the zoning code, triplex projects have to pave over enough land for a vehicle to make a three-point turn, unless granted an exemption by the city traffic engineer. They are also subject to a raft of landscaping, lighting, drainage, and architectural requirements. Single-detached houses or duplexes of the same size, or even larger, don’t have to meet the same requirements, making them cheaper to build.

“In Anchorage, when you go from a duplex to triplex, suddenly you need an electrical engineer doing a lighting analysis of the driveway,” said local developer Andre Spinelli, who was part of a different design team. “It’s literally the same analysis that’s applied to a commercial parking lot to make sure it’s safe.”

Spinelli spent nearly $30,000 on a storm drainage analysis and installation of two storm drain manholes for a triplex he built near West Dimond Boulevard. “I could have drawn the same box with the same square footage and called it a duplex and not had to do that,” he said. Spinelli estimated that by adding the third unit, a developer could expect to incur $50,000 to $70,000 in extra costs for the same footprint.

“Financially speaking, you’re better off building a bigger duplex. That’s what’s frustrating about all these codes,” Spinelli said. “By right, a person is allowed to build the tallest, ugliest eyesore of a duplex that covers 40 percent of the lot, and then the code and permitting process add so much burden trying to nitpick how to build a triplex or a smaller duplex with an accessory dwelling that it becomes cost-prohibitive.”

Given these regulatory demands, no more than five triplexes have gone up in Anchorage in a single year since 2001, according to data provided by Cook Inlet Housing Authority. Some years, no developer has built a single triplex.

What about a duplex plus in-law apartment?

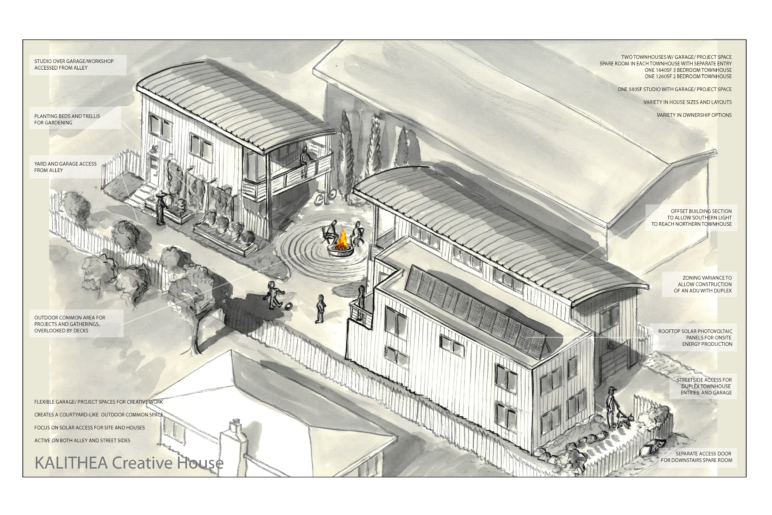

Another way to allow for three homes on a lot? Pairing a duplex with an accessory dwelling unit (ADU). Another team, Fairview resident Omega Smith, local developer Andre Spinelli, and architects Evelyn Rousso and Garret Burtner, went this route. Their duplex-plus-backyard-cottage design included space for making music or art, plus a communal yard, garden, and fire pit. Solar panels lined the duplex’s roof, with its barrel vault ceilings, balconies, and clerestory windows. The curved roofs were a nod to the Quonset huts that once dotted the city and served as aircraft hangars on nearby Merrill Field. The team also included three garage parking spaces and two more outside.

But this middle housing style is currently a no-no in Anchorage, even if the total square footage is considerably lower than that of the many large single-detached homes throughout the city. The city has long allowed owners of single-detached homes to add ADUs. An ordinance set for introduction this year would allow one ADU per duplex as well, potentially opening up about 7,000 duplex homes across the city to ADUs.

Other cities and states have either begun to allow the duplex-plus-ADU combo or are considering it. In 2018, Vancouver, British Columbia, allowed one ADU for each duplex unit. In 2019, California allowed ADUs on lots with multifamily dwellings. Seattle allows one ADU per dwelling in its zones for small-scale multifamily homes.

Let the market decide how many parking spots to build

Outside downtown, Anchorage mandates a minimum number of spaces per housing unit. Parking mandates tend to overestimate actual parking demand and force overbuilding.

A glut of parking may sound like a happy problem to anyone who’s spent time looking for a spot. But consider the downsides: Building excess parking makes housing less affordable. It wastes land that could have gone to boosting the housing supply and makes homes more complex to design and expensive to build. And ultimately, renters and homebuyers bear the cost of excess parking, even if they don’t own a car.

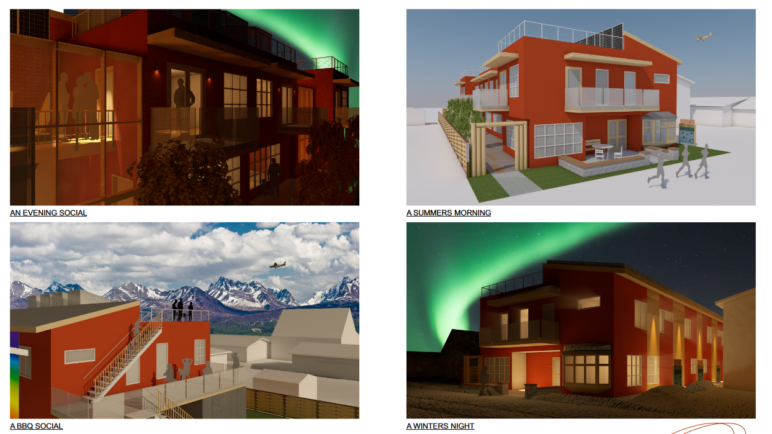

Reducing the parking burden on developers requires design choices, in both the public and private sectors, that promote an array of alternatives to driving. A third team—architect Lawrence Jorgensen, Fairview resident Allen Kemplen, and developer Seth Anderson—wanted to help residents go car-free or car-lite. The team’s cohousing/coworking co-op lets residents who work from home limit their driving to errands or weekend activities. The design included a greenhouse and raised garden beds so residents could grow more of their own food and perhaps cut back on grocery runs. And there are bike racks, of course.

“The reason we’re having problems is that the framework is built for the automobile.” –Allen Kemplen, Fairview resident and Anchorage Area Planner, State of Alaska – Transportation

“The reason we’re having problems is that the framework is built for the automobile,” Kemplen said in a March 2022 interview. “That square footage around the automobile can be used for something else, like additional living space or live-work space.”

The team estimated the total development cost at $830,000 and proposed a co-op model of ownership. The cooperative would own the land, buildings, and common areas. Member-owners would have control over their respective buildings and the overall property. Kemplen, who is also transportation planner for the state of Alaska, said not owning a vehicle can make home loans more attainable because banks look at discretionary income when deciding how much to loan. All things equal, a bank could decide to loan more money to an applicant who’s not saddled with car and gas payments.

Still, recognizing that vehicles will likely always be part of the transportation mix, the team provided all the parking spots mandated by city code. Anchorage requires between 1.25 and 2.5 parking spaces per multifamily unit, depending on the size and number of bedrooms. Single-detached homes require even more: 2 or 3 spots per unit depending on square footage.

Of course, ditching mandates doesn’t mean developers won’t build parking. They’ll just get to make the call on how many spots to provide, rather than the city deciding for them. Many North American cities, including Minneapolis, Edmonton, and Houston, have rolled back parking requirements. And the state of Oregon in July just approved the largest rollback to parking mandates in modern US history. In Anchorage, parking mandates apply everywhere but downtown. A set of parking code revisions, inspired in part by the design contest, will go before the Anchorage Assembly in the next few months.

A few members of the Anchorage Assembly have floated the idea of tossing out parking mandates. Doing so would gradually allow for more efficient use of city land. A more compact cityscape is fundamental to a less car-centric city, where walking, biking, and taking public transit are all doable, attractive options. (Anchorage’s recent school bus shortage highlighted the lack of transit options kids have for getting to school.) Cars and trucks would still be in the mix, but more transportation choices could make Anchorage life more affordable, healthy, and efficient. Drivers would benefit as well. Take some cars off the road, and the remaining drivers could reach their destinations more quickly. And the city could devote more land to homes for people instead of spots for cars.

Setback requirements

Setback requirements are one of the many seemingly innocuous restrictions that exacerbate a shortage of housing. Setback rules dictate how far away buildings must be from the property line. They can allow for airflow and light and make space for utility lines, but in many situations, setbacks merely limit efficient use of land.

A fourth team, made up of resident Josh Harris, designer Jae Shin of KPB Architects, and Chad Taylor of Intrinsic Landscape, found a creative way around the setback constraints in Fairview by designing a subterranean triplex. Since the design required no building space above ground, they could design more spacious units that crossed the setback boundaries (and exceeded above-ground lot coverage limits).

The team used the open space for a vegetable garden, skylights, and communal outdoor seating. All the units faced south and included heated courtyards, featuring trees, ornamental grasses, and barbeque grills. The neighbors’ view of the Chugach Mountains and winter exposure to southern sunlight remained unobstructed. Placing the units underground also helped soundproof against air traffic noise from nearby Merrill Field.

Shin said technically the project would not be challenging to build, but at $875,000 (in pre-pandemic dollars), it would be expensive. The design team knew this was a farfetched project for financial reasons, but “wanted to do something that was more provocative because we knew Cook Inlet Housing Authority was looking for new ideas,” he said.

The setback requirements currently in Anchorage’s land use code to build a multifamily home at 820 Nelchina are 10 feet from the front of the property, 5 feet on either side, and 10 feet from the rear since it abuts an alley, with some exceptions. The city may consider reducing or tweaking setback requirements to encourage more efficient land use. For instance, reducing or eliminating setbacks for non-garage structures (like ADUs) along an alley could make sense, as could allowing homes to be built closer to the sidewalk. Allowing stoops, covered porches, and balconies within setback zones could help as well.

The city is considering proposals that would allow ADUs to encroach on setbacks along an alley at the rear of a property, as well as eliminating setback requirements for residential buildings downtown. (Most large cities have zero setbacks for large apartment buildings in mixed-use zones, like downtown.)

Anchorage can help household budgets through more efficient land use

Anchorage is not running out of land. But zoning codes prevent Alaska’s largest city and its residents from using the land efficiently. Like other cities across North America, they’ve locked themselves into building the most land-gobbling, least affordable type of housing on the planet. Crowning single-detached homes as the most-favored housing type has stymied the city’s projected long-term growth by perpetuating the unaffordability and under-supply of homes. The problem worsened during the pandemic, when low interest rates juiced prices to record highs and exhausted inventory in cities large and small.

Anchorage is not running out of land. But zoning codes prevent Alaska’s largest city and its residents from using the land efficiently.

A return to an earlier period of American housing policy that allowed more homes of all shapes and sizes, would help bring more choice, affordability, and satisfaction to people seeking homes. There’s no reason Anchorage can’t lead the way back to a time when more homes with smaller footprints at better prices were allowed.

Fixing Anchorage’s land use codes won’t repair the housing market overnight. But doing so is one critical step to providing an attractive array of middle housing options at a wider variety of price points. Single-detached homes would still be very much allowed and available; the market would simply expand, with more options for all.

Comments are closed.