Takeaways

Approval voting (AV) is brand new and little studied.

AV hands voters a dilemma: pick your favorite but lose broader influence? Or try to block your least favorites but hurt your favorite?

We don’t know whether AV dampens extremism or tamps down negative campaigning.

AV in a top-two race, as in Seattle, could harm representation of minorities.

AV may violate “one person, one vote” and/or voting rights acts.

Ranked choice voting (RCV) performs better on each of these counts.

In short, RCV is less risky than AV.

Find audio versions of Sightline articles on any of your favorite podcast platforms, including Spotify, Google, and Apple.

Editor’s note: In two subsequent articles, Durning argues that approval voting would start no sooner than ranked choice voting in Seattle, if voters chose it in November, and shares a voting-rights law firm’s evaluation of the two options’ legality.

Seattle voters will decide in November whether to adopt approval voting, ranked choice voting, or no change to their primary election ballots. What do the research literature and practical experience say about these two alternatives to pick-one voting? They say a tremendous amount about ranked choice voting (RCV), and Sightline has summarized the lessons in tens of thousands of mostly encouraging words over years. But they say much less about approval voting (AV). This article summarizes what’s known.

Approval voting has intriguing features. It is simple to implement and easy to tabulate. Its proponents plausibly claim worthy benefits, including more moderate victors and less negative campaigning. It is worth experimenting with and deserving of study. We stand to learn more over time because two communities have recently adopted it. They are, in effect, conducting the clinical trials for this new voting method.

Both intuition and theory say AV will elect people who are, if not necessarily voters’ favorites, at least unobjectionable to most. They would be “consensus-style candidates,” say AV proponents. That tendency to dampen extremism and reward competent, cooperative governance, I surmise, is a major appeal of AV for its proponents and financiers, and it’s a goal Sightline shares.

But adopting AV for primary elections for all city offices in Cascadia’s largest city would be risky. For all its appeal, AV is a novel, unproven, and legally untested system for elections, and it has weaknesses that should give us pause.

For all its appeal, AV is a novel, unproven, and legally untested system for elections, and it has weaknesses that should give us pause.

The most salient fact about approval voting is that we do not actually know much about how it operates in the real world, not just in simulations or in academic papers or in the minds of schemers on Twitter or Reddit but in the pressure cooker of actual government elections, where campaigns rage, TV ads promise and malign, tempers flare, and hopes soar. This is where voters face the unavoidable dilemma into which AV forces them—that is, between helping their favorite and guarding against their least favorite.

We do not know if AV will deliver what it promises (moderation and a dampening of extremes), but we have reasons for doubt. We do not know if AV will lead to fair representation or pass court muster, but we have cause for caution. For these reasons, adopting it in Seattle in November would be risky, especially when Seattle can adopt the well vetted and helpful alternative of ranked choice voting instead. Let’s take a closer look at why.

1. Approval voting is too basic to represent a voter’s preferences

Let’s start with the voter’s experience.

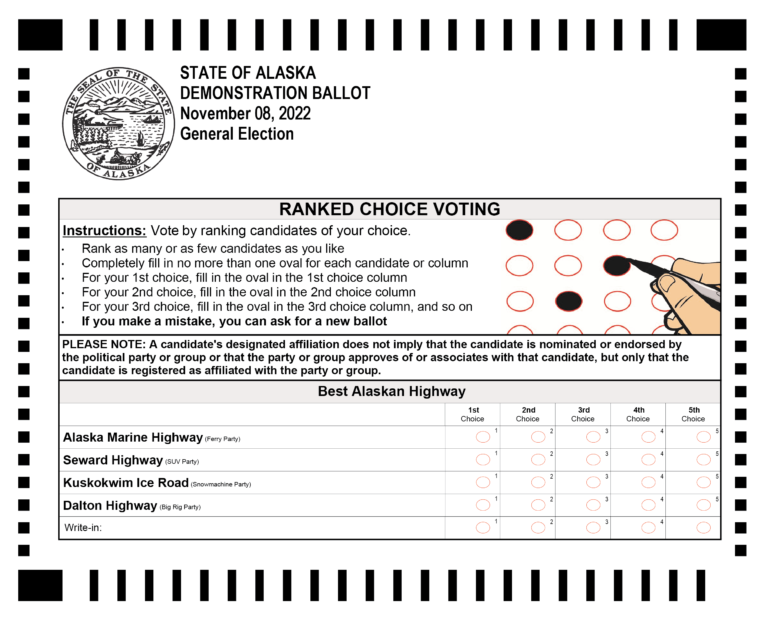

For voters, approval voting, like ranked choice voting, is an alternative to old-fashioned, pick-one voting. In it, you can fill in the bubbles next to as many candidates as you like. Whichever candidate gets the most approval votes wins.

It seems simple, and simplicity is appealing. AV is easy to understand and easy to tabulate. Unfortunately, its simplicity also holds weakness. Indeed, simplicity can make approval voting frustrating for voters.

Approval voting seems simple, and simplicity is appealing. Unfortunately, its simplicity also holds weakness.

The defining feature of approval voting is that it’s binary: approve or not, bubble filled or blank, yes or no. You approve just your favorite. Or your favorite and your second favorite. Or your top three. Or any number you choose. It’s up to you. Simple.

What you cannot do is convey any other preferences. No rankings. No ratings. No way to say that you love Nader but would settle for Gore, that you’d really like Perot but could live with Bush Sr., that you’d be elated with Biden, could get excited about Klobuchar, would be satisfied with Booker, and could tolerate Mayor Pete.

If your preferences are black and white, with no shades of gray, AV may be for you. Otherwise, the more you think about it, the more confounding it becomes. If you actually care who you vote for, you have no good option. Approve Elizabeth Warren and you’ve maximized your help to her but exerted no influence over the rest of the race. Fill Bernie’s bubble too, and you’ve just halved the weight of your Warren vote. You’re now helping them equally. Add Mayor Pete and you’ve cut your weight in thirds. Every candidate you approve dilutes your other votes.

If your preferences are black and white, with no shades of gray, AV may be for you. Otherwise, the more you think about it, the more confounding it becomes.

You have to decide whether to minimize the chances of your least favorite winning (by approving all but Trump, for example) or gamble by voting for your favorite (all in for Ben Carson, for example). The more you care, the more painful the choice. It’s not so simple after all. And that’s why most people just fill the bubble for one candidate, as discussed below.

For now, though, focusing just on voters’ individual experiences, what’s most eye-rolling about approval voting is that, well, AV acts as if no one had ever invented numbers. Its binary nature is not only woefully constraining but also entirely unnecessary.

And from the voter’s perspective, that’s the most basic reason that ranked choice voting is less risky than approval voting. Ranked choice ballots let you vote for candidates in order of preference, the way humans do… pretty much all everyday decisions they make that offer a few options: what to order for lunch when the kitchen has 86’d your favorite, which movie to watch when Netflix doesn’t have the classic you were craving, which household costs to prioritize over others in a tight month.

And ranking your second doesn’t hurt your first choice. RCV ballots differentiate among alternatives and reflect the nuances of your views. Marking Warren second doesn’t hurt Bernie if you’re on the Bernie train. Voting for Bush Sr. second doesn’t hurt Perot if you’re in the tank for Ross. Ranking Biden lower than Pete doesn’t hurt the mayor if he’s the one you like best.

That’s the right kind of simple.

2. Approval voting is new and unproven

Approval voting is new

Approval voting is new to government elections. So far, worldwide, only midsize St. Louis, Missouri (with less than half Seattle’s population), and Fargo, North Dakota (with one-sixth), have used it for elections. Between them, they’ve only used it three times, all since June 2020, with a total of fewer than 100,000 ballots. Three times, ever, anywhere in real-world, government elections.

Some 11 million voters in the United States now live in RCV jurisdictions that in total have completed hundreds of RCV elections, and Americans have cast tens of millions of RCV ballots.

In contrast, ranked choice voting has long histories in Australia, Ireland, New Zealand, and Scotland, and in the United States, its use is growing steadily. Some 55 US jurisdictions are already—or will soon be—employing it. They include the states of Alaska and Maine; blue cities including New York, Minneapolis, and San Francisco; more than a dozen red cities and towns in Utah; and six states where parties use it for presidential primaries. Some 11 million voters in the United States now live in RCV jurisdictions that in total have completed hundreds of RCV elections, and Americans have cast tens of millions of RCV ballots. In Washington state, voters will consider RCV in November not only in Seattle but also in Clark County (which surrounds the city of Vancouver, Washington, in the state’s southwest corner). In Oregon, it is already used in Benton County, which is home to Corvallis, and will be on the ballot in both the city of Portland and surrounding Multnomah County.

Approval voting is unproven

From all of this experience and the exertion of researchers, we can speak with confidence about RCV. A recent compilation that adds to the robust body of research findings, for example, tested some claims of RCV proponents and critics and concluded that RCV is safe and generally helpful, though perhaps not the panacea some proponents imply:

Consistent with previous RCV research, most of the studies in this series found RCV to be either a comparable or modestly better alternative to our standard “first-past-the-post” or plurality method.

RCV, it continues, yields small improvements on measures such as rates of voter error and does no harm on other measures, such as racial polarization. The findings of this new set of papers are quantitative, peer reviewed, and published for all to debate. They add to the terabytes of accumulating PDFs of empirical research. I might quibble with some conclusions or invoke RCV benefits not studied, but the point is that we can debate RCV based on empirical analysis. Almost no analysis of AV’s real-world application exists. It’s too new.

Instead, AV proponents are left to argue based on simulations and math. The Center for Election Science (CES), the world’s main AV promoter (and the largest funder of Seattle’s AV campaign), lays out a series of arguments for AV on its website, and they’re interesting. Almost every one of them, though, is supported only by theory. CES staff write, for example:

Computer simulations using Bayesian regret calculations . . . demonstrate better utility outcomes in elections using approval voting versus RCV even if all approval voters were tactical and all RCV voters were honest.

Um. What?

Seriously, though. Analysis like this does form interesting theory. Developed by a small cadre of smart, sincere mathematicians and thinkers, such as William Poundstone, Clay Shentrup, and Warren Smith, AV theory warrants serious consideration, though it’s far from unarguable. An equally smart and serious set of scholars, including James Green-Armytage, Jack Nagel, and Nicolas Tideman, contest it fiercely. In the end, such theoretical arguments may be unavoidable. All voting systems have theoretical flaws: Nobel laureate Kenneth Arrow proved that point 70 years ago. So choosing one system over another is about choosing which flaws are the least bothersome. And those choices inevitably involve value judgments—judgments best made based on empirical data from actual elections, not just from theory.

Again, AV theory is important work, and it justifies trying AV in places like Fargo and St. Louis, which had barriers to RCV. It justifies studying the results closely in those places. It’s promising. It might even justify testing AV in elections for offices where skills and competence matter a lot, and ideology should not matter at all, like election officials or county auditors. But it provides little basis for thinking AV is ready for choosing the political leaders of Seattle.

AV is like a potential new medicine that performs well in computer simulations and in animal trials and is now in its first clinical trials. Its sponsors are gathering information from the trial in two cities and are hopeful about the outcome. But it’d be dangerous to jump to universal distribution just yet, before anyone has ascertained if it’s safe and effective.

Many—indeed, most—drugs don’t make it through all the phases of clinical trials, because simulations and lab results cannot anticipate the complexities of real life. Elections are similar: RCV has survived its battle testing in the heat of actual campaigns, and it works well. AV is just starting that trial.

AV promises moderation, but . . .

Proponents argue that AV will dampen extremism and elect widely acceptable centrists. Seattle AV leader Logan Bowers told The Stranger, for example, “Right now the camps get pretty Orthodox—you got to be all in or all out, but there’s a lot of voters that are kind of in the middle. I think you would see more candidates adopt a lot of the policies that are just actually popular with voters.”

This argument sounds plausible, but so far, it’s not coming true. In the three AV elections to date, the winners were almost all well-established incumbents or candidates who clearly would have won anyway. And the one controversial, far-right incumbent in office in Fargo, David Piepkorn, who stood for reelection under AV? He won easily. So much for dampening extremism.

In the three AV elections to date, the winners were almost all well-established incumbents or candidates who clearly would have won anyway…

A reason to doubt the moderation claim is that in this (again, tiny) sample of AV elections, most voters only approved one candidate. In voting-scholar lingo, they “bullet voted.” That is, they just picked one candidate and voted as if AV didn’t exist, as if they were still in a conventional, first-past-the-post system. But the more people bullet vote, the more AV becomes indistinguishable from that system it’s trying to replace.

And it’s not that people are uninformed: bullet voting makes sense in AV. If you prefer a candidate, bullet voting is how to help him or her the most. Candidates understand that fact, and they tell voters. Said Fargo Mayor Tim Mahoney during his reelection campaign in the June AV election, “I would probably bet that every candidate says just vote once because that has more power as a vote.” Likewise, one of his challengers, Republican state representative Shannon Roers Jones, said at the launch of her campaign, “It will be important for me to convey to people . . . that the most effective way to elect the person they care about is to vote only for that person.”

…and the one controversial, far-right incumbent in office in Fargo, David Piepkorn, who stood for reelection under AV? He won easily. So much for dampening extremism.

Fargo and St. Louis voters listened, or they figured out AV’s internal logic for themselves. Most of them seem to have bullet voted. Elections administrators in neither city have released data on approval votes per ballot, but estimates are possible (see appendix). Apparently, between 50 and 90 percent of ballots were bullet voted, depending on the election and the race. In contrast, in ranked choice voting, between 10 and 40 percent of voters tend to bullet vote, ranking only a first choice.

If most people bullet vote, how much moderating impact can AV really have? Over time, AV in Fargo and St. Louis will tell us more, but for now, we cannot know. AV is just too new.

. . . RCV actually delivers moderation.

In Seattle, curiously, the media have characterized RCV as serving the interests of the left and AV as serving the interests of the center. That’s wrong on both counts. AV is a political unknown, and RCV favors neither left nor right but broadly popular candidates who also have a base of strong support. Perhaps that’s why extremists oppose it, from Donald Trump on the right to Kshama Sawant, Seattle’s one socialist city council member, on the left.

RCV favors neither left nor right but broadly popular candidates who also have a base of strong support.

The track record of RCV is one of victories, mostly, for centrists: Virginia’s Governor Glenn Youngkin was the most moderate Republican in his RCV primary. New York City Mayor Eric Adams was the most moderate of Democratic frontrunners in his RCV primary. Maine’s Democratic Congressman Jared Golden won an RCV election in a swing district by hewing hard to the center. Alaska’s moderate Senator Lisa Murkowski is a rare Republican who voted to remove President Trump yet is now positioned to win reelection. She is likely to survive a challenge from a Trump-endorsed right-winger thanks to Alaska’s new open primaries and RCV general election.

AV promises civility in campaigns, but . . .

Proponents suggest AV improves candidates’ civility with one another in political campaigns. Seattle’s AV campaign, for example, claims that AV elections “make politics less divisive. Campaigns won’t fight each other over voters—they’ll fight for wider support.”

Why would AV candidates stay positive, when approvals for others dilute their own support?

So far, though, we have no empirical evidence of this effect. In fact, polling from Fargo showed that voters perceived the June 2022 AV campaign as more negative, not more positive, than normal. It’s just one data point, but it aligns with the incentives of AV: why would AV candidates stay positive, when approvals for others dilute their own support?

. . . RCV actually delivers civility in campaigns.

RCV does change the tone of campaigns and of governing, because candidates (and incumbents) want not just first-place votes but also second- and third-place votes. RCV candidates have less incentive to “go negative” than in the status quo. A lot of research and experience backs up this conclusion.

3. Approval voting is legally untested and might worsen representation

Approval voting may violate a basic principle of US election law: one person, one vote. Courts might throw it out.

What’s more, the AV proposal on Seattle’s November election might underrepresent the city’s political minorities, racial and otherwise. That would be unfair and might lead courts to throw out AV under federal or state voting rights acts.

Either way, the election system might end up in disarray.

AV’s basic method is legally untested

In an approval voting election, I can vote for five candidates while you vote for one, and each of our votes will carry equal weight. Doesn’t that mean I have five times as much say as you do? Isn’t that a glaring violation of “one person, one vote,” the 1964 US Supreme Court principle that “the weight and worth of the citizens’ votes as nearly as practicable must be the same”?

In a similar vein, Washington law says, “Nothing in this chapter may be construed to mean that a voter may cast more than one vote for candidates for a given office.” In a debate about AV in Olympia in 2019, reported by The Olympian, Thurston County Auditor Mary Hall replied to the question of whether it’s legal: “It’s not. There would have to be legislation to allow (it).”

Seattle’s AV proposal might produce worse representation for people of color and violate voting rights laws

Seattle’s AV measure applies only to selecting winners of open, top-two primaries. Converting the general election to AV (or RCV or anything else) would require a change in state law (which Sightline and others have been working toward for years). Such a change would allow localities across Washington to engage in the kind of thorough evaluation of voting methods that Portland, Oregon, has undertaken of late, leading to its charter reform proposal that includes multi-winner RCV—a promising form of proportional representation tailored to Portland’s needs.

In Seattle, though, the only legal option is to change the top-two primary either to AV or to RCV, and in this context, approval voting is not just an intriguing, unproven novelty; it could be a step backward on fairness. Top-two AV in Seattle might worsen representation of the city’s voters. How?

In Seattle’s existing method, everyone gets one vote, and the two most popular candidates move from the low-turnout, less representative August primary to the high-turnout, more representative general election in November. The first-place finisher represents the largest bloc of primary voters. The second-place finisher represents the second-largest bloc.

With AV, the same bloc of the electorate (perhaps the older, home-owning, educated people who tend to vote in primary elections) could pick both of the winners, dictating the candidates that general election voters choose from. That is, instead of the largest two blocs each picking one candidate, the largest bloc would select both. And that would be representational backsliding, an egregious unfairness.

The root of the issue is that the most informed voters can increase their influence. As RCV proponent Rob Richie of FairVote wrote in a 2011 critique of AV and similar methods, “Once aware of how approval voting works, strategic voters will always earn a significant advantage over less informed voters.”

Using that advantage to sway election outcomes is no certainty, of course; it depends on many people voting the same way. Still, it’s a worrisome prospect, and it’s a worry that justifiably preoccupies some of Seattle’s leaders of color. More reason for concern comes from University of Missouri’s professor David Kimball, who assembled evidence in St. Louis that voters in majority-white wards cast more approval votes on their ballots for mayor than did those in majority-Black wards.

If white areas of Seattle approve more candidates per ballot than do areas home to more people of color, as happened in St. Louis, would that not violate the federal and Washington state voting rights acts? Racially polarized voting plus disproportionate influence for white voters are at the heart of those laws.

Even if, by the vagaries of logic or lawyering, the legal system ultimately permits AV, the court gauntlet might still consume months. It could even confuse the schedule of certifying elections and swearing in winners. That’s yet another reason for caution about approval voting.

RCV represents people better

Ranked choice voting, meanwhile, sidesteps each of these legal perils: each voter gets one vote , and it can transfer in its entirety from disqualified to still-contending candidates, as if in a series of “instant runoff” elections. RCV does not create racially polarized voting or disproportionate influence by white voters, and it’s been tested more than a dozen times in US and state courts. It’s emerged unscathed.

RCV also gets good marks on electoral representation. In a top-two primary, RCV would be a modest improvement on pick-one voting. Eliminating the least popular candidate and reassigning ballots to those voters’ next favorite choices, then repeating the process until only two candidates remain, maximizes the chances that the two most popular candidates proceed to the general: the top vote-getter is chosen by the largest group of voters. The runner-up is chosen by the second-largest group of voters. And unlike in AV, those groups of voters will always be different people.

(9/19/2022 UPDATE: Sightline commissioned a legal analysis from a Seattle-based law firm with experience in election and voting law. Its conclusions include: RCV is legally safe. AV runs a small risk of being thrown out by courts even before implementation because of its apparent violation of the state election law mentioned above. AV also faces a small risk of being thrown after implementation, because it could violate federal or state voting rights acts. Read the legal memo here or Sightline’s summary here.)

4. AV is risky; RCV is tested and delivering the benefits voters want

AV is a novelty: intriguing and worth attention but not yet proven or well understood. Adopting it in Seattle in November, for use in top-two primaries, would put voters on the horns of a dilemma: do they rally to their favorite or spread their votes across all they can tolerate? Adopting it might do little or nothing to dampen extremism or tame negative campaigning; indeed, RCV would be a safer means to those ends. And adopting AV runs the risk of degrading representation of minorities in Seattle, an injustice and an invitation to court challenges.

For all the reasons I’ve laid out in this article—a dilemma for voters, a novel system with unknown characteristics, low confidence it will deliver moderation or a more positive political climate, caution about fairness and court review—AV seems a risky choice for Seattle in 2022. It’s just too novel—a promising new treatment for our democracy that needs to finish clinical trials before we start using it.

Meanwhile, RCV is tested and ready, no panacea but a modest improvement and free of the uncertainties that bedevil AV. From what we know now, therefore, RCV > AV.

Appendix: bullet voting in AV (and RCV)

In Fargo, an opinion poll by the national pro-RCV research and advocacy organization FairVote estimated that 60 percent of voters bullet voted in the seven-candidate AV mayoral election of June 2022. For sake of comparison, in New York City’s contested Democratic RCV primary for mayor in September 2021, which nominated Eric Adams, only 13 percent bullet voted, according to a recent study by the City University of New York. In RCV elections overall, some 29 percent of participants bullet vote, on average, according to a dataset on RCV elections maintained by FairVote, and the more competitive the race, the fewer people bullet voted, dropping toward 10 percent in the highest-stakes, highest-profile races.

Lacking ballot-by-ballot data on approvals, we can glean insight from averaging approvals given over ballots cast. Such figures do not reveal how many people bullet voted, because they do not show whether, for example, many people approved two candidates each or a few people approved ten candidates each. Still, they give a sense.

For context, in the Fargo mayoral race just discussed, with its 60 percent bullet voting rate, voters approved an average of just 1.5 candidates from a field of seven. The mayoral primary in St. Louis’s one AV election, in March 2021, selected two finalists from a field of four, and in these races, voters approved an average of 1.6 candidates. If the voting pattern in this race was like that in Fargo, that figure might correspond to a bullet voting rate of 50–60 percent. For comparison, I looked at all recent four-candidate RCV races from the FairVote dataset—13 of them—and found that voters ranked 2.3 candidates apiece on average, and about 40 percent of them bullet voted.

In St. Louis’s city council AV primary, two candidates qualified to go on to the general election for each seat, and voters approved an average of just 1.1 candidates per seat, though the races had three candidates each. The low approval rate of 1.1 per ballot corresponds to a bullet voting rate of 90 percent or higher. Mathematically, if 90 percent of voters bullet voted and 10 percent approved two candidates, you’d get 1.1 approvals per ballot. In comparison, in all 17 recent three-candidate RCV races in the FairVote dataset, voters ranked 2.1 candidates, on average, and fewer than 40 percent of them bullet voted.

Overall, therefore, bullet voting rates in Fargo and St. Louis AV elections were likely between 50 and 90 percent, while RCV bullet voting rates in comparable elections have been between 10 and 40 percent.

Comments are closed.