This article is part of the series The Costs of Parking Mandates

Find audio versions of Sightline articles on any of your favorite podcast platforms, including Spotify, Google, and Apple.

It’s not every day that elected leaders ask for less authority. But at a California Assembly committee hearing in April, two out of every three representatives for local governments testified in support of a new bill that would limit their zoning authority.

AB 2097, introduced by Assemblymember Laura Friedman, would prohibit cities from mandating off-street parking near high-quality transit, in an effort to increase housing production across the state.

For decades, nearly every city in North America has required new buildings to have a specific number of parking spaces, regardless of whether they were downtown or surrounded by empty parking lots. These regulations were successful in building a lot of parking spaces, even as housing for Californians has grown harder to come by. In the highly sought-after Bay Area, there are twice as many parking spaces as people.

Some of the cities represented, like San Diego and Emeryville, have already done away with local rules requiring off-street parking. But elected officials from Gilroy to Culver City had not, and they were hoping the state would intervene in what is often a contentious land use fight.

The sentiment is not just a Californian one. On the other side of the border in Oregon, Talent city council president Eleanor Ponomareff told a state land use board the same thing earlier this year, in regards to a policy change that would significantly reduce parking requirements in Oregon’s metro areas. “Implementation at the state level means fewer battles we, at the local level, have to fight,” she said. Officials from Talent have their hands full already, as they recover from a 2020 wildfire that destroyed one- third of local homes, worsening a pre-existing shortage of affordable housing. As governments across Cascadia try to course-correct decades of underbuilding housing, its critical to acknowledge the limits of what local governments can achieve on their own.

Back in Sacramento, one of the local officials at April’s hearing was Colin Parent, who serves on the City Council of La Mesa, a small suburban community ten miles east of San Diego. Every home in La Mesa is required to have two off-street parking spots, whether or not residents need them. Even though Parent is in favor of eliminating parking requirements, his fellow councilors have little appetite for a politically difficult reform. “That’s not an issue on the table,” Parent said. “I think that’s similar to most cities in California.”

Assembly member Friedman knows this all too well. She recalled a case from her time on the Glendale City Council when a family wanted to add a bathroom to their home, but to do so would have had to build a three-car garage to bring the home up to current codes. The family never ended up building their bathroom, and Friedman wasn’t successful in building more flexibility into the zoning code. She lost by one vote.

Local parking requirements add up to a statewide housing shortage

There’s reason to believe that most voters prioritize housing over parking. But most voters don’t show up to zoning hearings. Instead, local zoning meetings often go something like this: the more localized a land use change is, the more heavily the scales are tipped towards the status quo. Current residents can easily visualize the downsides of new development, like more traffic or a blocked view. But the future residents who will benefit from those new homes aren’t there to advocate for themselves in the same way.

This imbalance in political power makes zoning changes difficult, even in the most progressive cities. As a result, local leaders can be hesitant to stick their necks out and instead choose to focus on other issues. Michael Manville, an urban planning professor at UCLA, thinks state action is appropriate. “Even though things are sort of trending in the right direction, the fact is that the vast majority of local governments don’t show a lot of interest in getting rid of their parking requirements,” he told me.

But by not taking it on, La Mesa’s requirement of two parking spaces per home affects more than just La Mesa. Parking can cost $30,000 to $75,000 per space to construct, adding onto the price of each unit and reducing how many new homes can fit into the allowed building envelope—or worse, preventing new homes from being built at all. So when people who want to live in La Mesa can’t find a home within their budget, they look elsewhere, increasing competition for homes in slightly more affordable towns nearby. When most cities require car parking for new housing, those regulations distort entire housing markets.

Strict parking requirements are a “classic case of a collective action problem,” explained Manville. “What seems good for each individual city sums to an outcome that isn’t optimal for the state.” From 1980 to 2010, California came up 70,000 to 100,000 homes short each year to keep pace with population growth, according to a report by the Public Policy Institute of California. In the most recent decade, for every one new home built there are three new Californians.

“The housing crisis in California is a statewide issue,” explained Friedman. “That’s why policies that prevent barriers for housing rise to the level of statewide action.”

Abundant housing solutions require widespread parking reform

The bill would not stop new parking spaces from being built. Rather, it gives each project the flexibility to have the amount of parking it needs, as long as it is within a half-mile of a train station or frequent transit line. That would make life easier for affordable housing developer Meea Kang. “Every single time I bring a project forward to get entitled, I have to ask for a parking reduction,” she said.

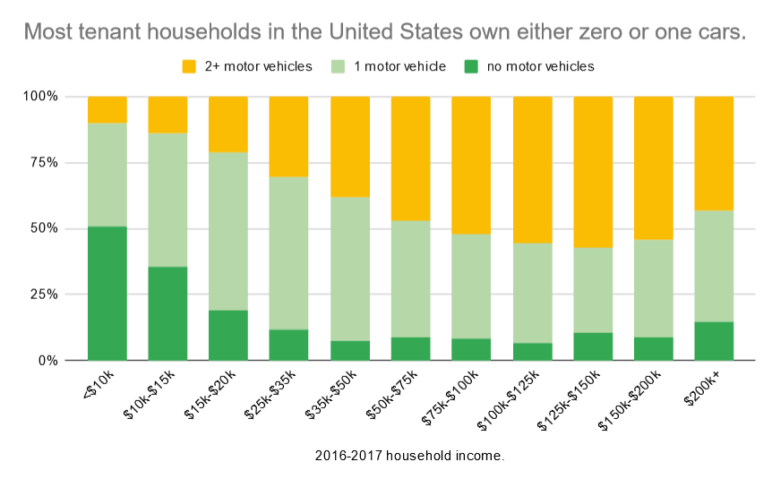

The assumption that each household has a minimum of two cars doesn’t reflect today’s society, Kang explained. According to the most recent US Census, 52 percent of California renter households have one or zero cars. At the lowest income levels, people are the least likely to own a car, and would benefit the most from more housing options and cheaper rent that is possible without the cost of parking.

Last year’s version of Friedman’s bill, AB 1401, drew some concern that if cities were no longer able to trade lower parking requirements as a carrot for deed-restricted affordable housing under the state Density Bonus Law, construction of those homes would decline. But new data out of the city of San Diego showed otherwise. After eliminating parking requirements near transit in 2019, the city saw a boom of affordable housing instead of a bust. 2020 set a new record for the number of affordable homes entitled through the Density Bonus program, including a jump in buildings comprised solely of affordable units.

Hopeful reformers described the statehouse as a better stage politically for land use reforms. As the geographical scope grows, the negative impacts of change become more diffuse and lose power, while the benefits become sizeable enough to unite political allies. As Jerusalem Demas stated unequivocally in The Atlantic last month, “In the US, moving decision making from the hyperlocal level to the state level is the first step to fixing the broken development process.”

Despite parking requirements being in nearly every local zoning code, statewide regulation is relatively new. Washington* became the first modern state to cap parking mandates near transit for multifamily buildings in 2020. Later that year, Oregon’s state land use agency determined that requiring excessive parking for newly legalized duplexes, triplexes, and fourplexes constituted an “unreasonable cost.” Since then, states have tucked reduced parking requirements into middle housing bills, or tried to prohibit them alongside other exclusionary zoning practices, as New York is attempting.

California has tried to restrict parking requirements several times before. In 2011, AB 710, which would have capped parking requirements near transit at one parking space per unit, was narrowly defeated in the Senate, losing by just one vote at the end of the session. Last year, AB 1401 passed with bipartisan support in the State Assembly but was denied a vote on the Senate floor.

Cities won’t act until states do

Even as the housing crisis has worsened in California, not everyone agrees parking requirements are a problem that needs fixing. The California League of Cities opposed the measure on the grounds that local parking requirements should be left up to individual cities, just as their peer organizations in Oregon and Washington have. Santa Clarita defended city-imposed parking requirements, claiming that they “ensure residents and visitors have adequate and reasonable access to homes and businesses.” Going beyond just requiring parking spaces, Santa Clarita requires those spaces to be enclosed—that is, garages. (And many of those garages will end up becoming catch-all junk drawers instead.)

Friedman didn’t mince words for cities who want to retain local control. “I would throw back at them they have failed to provide housing for our residents,” she said.

Local leaders like Parent welcome state intervention. After California required cities to legalize ADUs and offer density bonuses for affordable housing, his city of La Mesa ended up going above and beyond what the state required. The same has happened in Portland and other Oregon cities, too.

“There’s no way we would have been able to do any of those ordinances locally if the state hadn’t acted first. The politics aren’t there for it,” Parent testified before state legislators in Sacramento. “I’m confident you’re going to see good faith implementation from local governments, as long as the legislature acts.”

*We previously stated Oregon was the first state to take major action limiting parking requirements, but Washington’s bill was signed into law in March 2020.