Takeaways

Fossil fuel interests in Canada are taking advantage of the Ukraine crisis to promote Canada’s languishing LNG export industry as a solution to the EU’s dependency on Russian gas.

But the EU plans to be fully off Russian gas by 2025: the same year that the first of British Columbia’s five LNG export proposals would be up and running.

What’s more, British Columbia cannot both frack the levels of gas needed to supply these LNG facilities and meet the greenhouse gas emissions cuts required by its own climate commitments.

Find audio versions of Sightline articles on any of your favorite podcast platforms, including Spotify, Google, and Apple.

A chorus of North American fossil fuel boosters is once again pushing for more pipelines and liquified natural gas (LNG) plants, this time purportedly to help Europe quit the 40 percent of its gas it imports from Russia. For example, Deborah Yedlin, CEO of the Chamber of Commerce in Canada’s fossil-fuel capital Calgary, declared, “We must resurrect [LNG] projects—on the east and west coasts. It is a moral imperative.”

But like previous arguments for completing the mostly languishing LNG proposals on Cascadia’s West Coast, in British Columbia, these new ones do not add up. BC LNG proposals are solutions in search of a problem. Their fuel cannot be ready soon enough to matter to Europe and cannot be extracted and burned without harming the climate.

Five LNG proposals remain in British Columbia, two the public can comment on now

Canada is home to a total of zero LNG export facilities. Of dozens proposed over the years in British Columbia, all but five are now dead. Most succumbed to a combination of market forces and concerted public opposition to fracking gas in eastern British Columbia and shipping it in liquified form off the Pacific Coast. The harms of fracking include health impacts like low birth weights, contaminated drinking water, degraded Indigenous land pockmarked with thousands of gas wells, and accelerated climate impacts.

Proponents of remaining BC LNG proposals (see table below) promise to begin operations between 2025 and 2030, but if their past records of delay are any guide, these promises will prove to have been little more than wishful thinking.

Indeed, just one of the projects has started construction at all and is only 50 percent complete. This project, the Can$40-billion LNG Canada, has already pushed back its opening date from 2023 to mid-2025, a forecast that’s likely to slip further. Plus, the new Coastal Gaslink pipeline that TC Energy is building to supply LNG Canada has suffered repeated delays and will distinguish itself as one of the most expensive gas pipelines in the world. TC Energy pegged the pipeline’s cost at Can$4.4 billion in 2012, boosted the estimate to Can$6.6 billion in 2020, and in February warned that costs had “increased significantly,” without saying how much. Controversy about the pipeline, which will carry fracked gas across the territory of the Wet’suwet’en First Nation, keeps mounting. Wet’suwet’en leaders recently called on the United Nations to investigate Coastal Gaslink for what they say is Canada’s violation of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

Two other projects, the Tilbury Phase 2 Expansion project and Cedar LNG, await environmental assessments. (Members of the public can comment on both until mid-April.) Woodfibre LNG in Howe Sound was issued its environmental approval in 2016 by then-Minister of the Environment and Climate Change Catherine Mckenna, but the project languishes behind obstacles and lacks some permits. The last live project, Ksi Lisims, is so new that its timeline is highly speculative; a consortium that includes fossil fuel interests and the Nisga’a First Nation, only announced it in July 2021.

| Project | Location | Estimated Annual Export Capacity (billion cubic meters of gas) | Estimated Completion Date | Current Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LNG Canada Phase 1 | Kitimat, BC | 19.3 | 2025 or 2026 | Under construction; about 50 percent complete |

| Cedar LNG | Kitimat, BC | 3.8 | 2027 | Undergoing environmental assessment. Public comment open through April 14, 2022. |

| Woodfibre LNG | Howe Sound, BC | 2.9 | 2027 | Received environmental assessment certificate, but missing some key permits. Construction has not started. |

| Tilbury Phase 2 Expansion | Tilbury Island Delta, BC | 3.5 | 2028 | Undergoing environmental assessment. Public comment open through April 10, 2022. |

| Ksi Lisims LNG | Pearse Island, BC | 16.6 | 2028 | In planning phase |

| LNG Canada Phase 2 | Kitimat, BC | 19.3 | 2030 | Not yet confirmed. Companies will decide in 2025 at the earliest whether to move forward. |

Source: Respective projects’ websites, accessed March 2022. Estimated annual export capacity converted from million metric tons to billion cubic meters, rounded to nearest tenth.

By the time BC’s LNG facilities open their doors, Europe plans to have eliminated its reliance on Russian gas

British Columbia’s LNG is purportedly destined for Asia, not Europe. But because the market for LNG is increasingly global, with nearly 40 percent of LNG now traded on the spot market or via short-term contracts, adding Canadian LNG to the global supply could help Europe overcome its supply shortage.

But the EU will be sailing away from Russian gas just as BC’s LNG arrives to dock.

Not quite two weeks after Russia invaded Ukraine, the European Commission outlined its new “REPowerEU” plan, which aims to reduce the EU’s reliance on Russian gas by nearly two-thirds before year’s end. About 60 percent of this reduction would come from securing alternate gas suppliers and the other 40 percent from lowering consumption of gas through efforts such as greater energy efficiency, heavier investment in wind and solar, and installation of millions of new heat pumps. Some, including the climate change think tank E3G, argue that these gas consumption reductions could go even further, including through a more ambitious ramp-up of renewable energy.

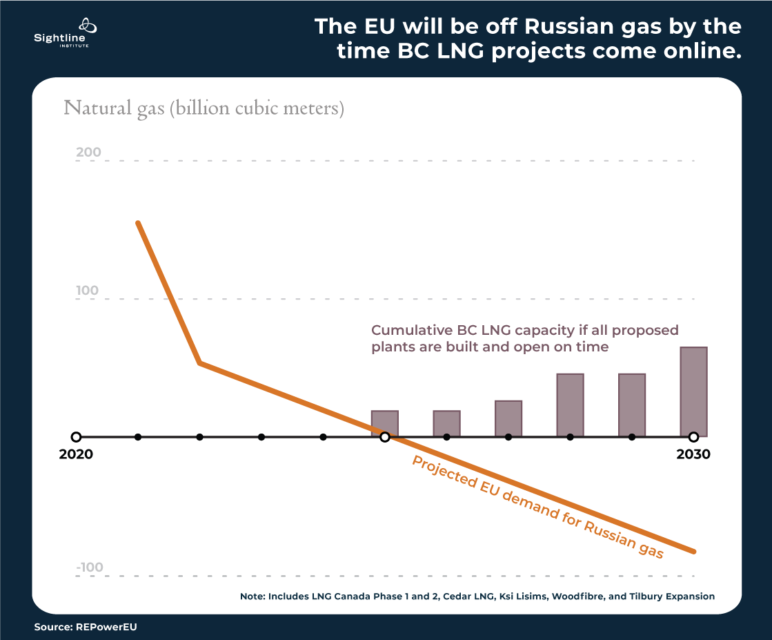

Under its new plan, by 2025, the EU will have either swapped suppliers or reduced demand for a total of 155 billion cubic meters (bcm) of gas: the amount it imports from Russia.1 As shown by the orange line in the chart below, 2025 is also the year when the first BC LNG project, LNG Canada, hopes to begin production. The gray bars chart the cumulative capacity of LNG Canada and the other proposed LNG projects and their start dates—assuming that they all defy prior projects’ pattern of delays and open on time. Even with this optimistic assumption, British Columbia will ramp up its LNG exports just when the EU no longer needs them or any other replacement for Russian gas.

Some analysts suggest that the EU’s plan is unrealistic and that the bloc will not be able to secure alternate supplies or reduce demand for gas so quickly. The global LNG market remains tight, with limited excess supply to redirect to Europe from other buyers. Indeed, REPowerEU sets higher ambitions than the International Energy Agency (IEA) laid out a few days earlier in its own plan.

However, even if the EU cannot secure alternate gas suppliers as quickly as it intends, the continent is clearly committed to weaning itself off gas in general. By 2030 REPowerEU would slash the EU’s gas consumption almost in half. Plus, high LNG prices may lead other countries, particularly lower- and middle-income countries, to rethink relying on LNG to fuel their economies, meaning British Columbia’s LNG projects, if completed, could contribute to a global supply glut. In March 2022 the industry-aligned Independent Commodity Intelligence Services (ICIS) forecasted that South Asia, Southeast Asia, and South America would consume 15 billion cubic meters (11 million metric tons) less LNG this year, equivalent to about 10 percent of the EU’s Russian gas imports in 2021. The Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA) recommends these countries leave behind LNG and instead invest heavily in renewables, which “have one-time upfront costs, but lack the ongoing, long-term, foreign currency-denominated fuel purchase requirement.” As the world turns away from natural gas in the medium term, British Columbia’s LNG projects, if completed, will just be sputtering on.

Plus, BC LNG runs afoul of climate timelines

British Columbia’s remaining LNG projects also conflict with the province’s climate commitment. The province pledged to reduce its greenhouse gases to no more than 60 percent of its 2007 levels by 2030. The message from scientists is unambiguous: fossil fuels have no role in a clean energy future. Short-term concerns about replacing Russian oil and gas risk obscuring this message. As UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres warned, “As major economies pursue an ‘all-of-the-above’ strategy to replace Russian fossil fuels, short-term measures might create long-term fossil fuel dependence and close the window to 1.5 degrees.”

The urgency of getting off fossil fuels applies to natural gas, too, which, despite being a dirty fossil fuel, the oil and gas industry still touts as a cleaner “bridge” fuel thanks to its lower carbon emissions when burned compared to oil and coal. Indeed, backers of BC LNG projects promote the alleged climate benefits of their projects, primarily by claiming that Canada’s LNG will replace coal-fired power plants in China.

But natural gas is not a bridge to anything except climate disaster.

Although natural gas burns cleaner than coal at the point of combustion, its overall carbon emissions, including production and transportation, can be greater than those of coal, in part because natural gas is mostly methane, which leaks. Methane is like carbon dioxide (CO2) on steroids: it causes 86 times more global warming than does CO2 over 20 years. Authorities are dramatically underestimating methane leaks from oil and gas wells, pipes, and other facilities, according to the International Energy Agency, and British Columbian methane leaks are 1.6 to 2.2 times higher than official figures estimate, according to a 2021 study supported in part by the BC Oil and Gas Commission.

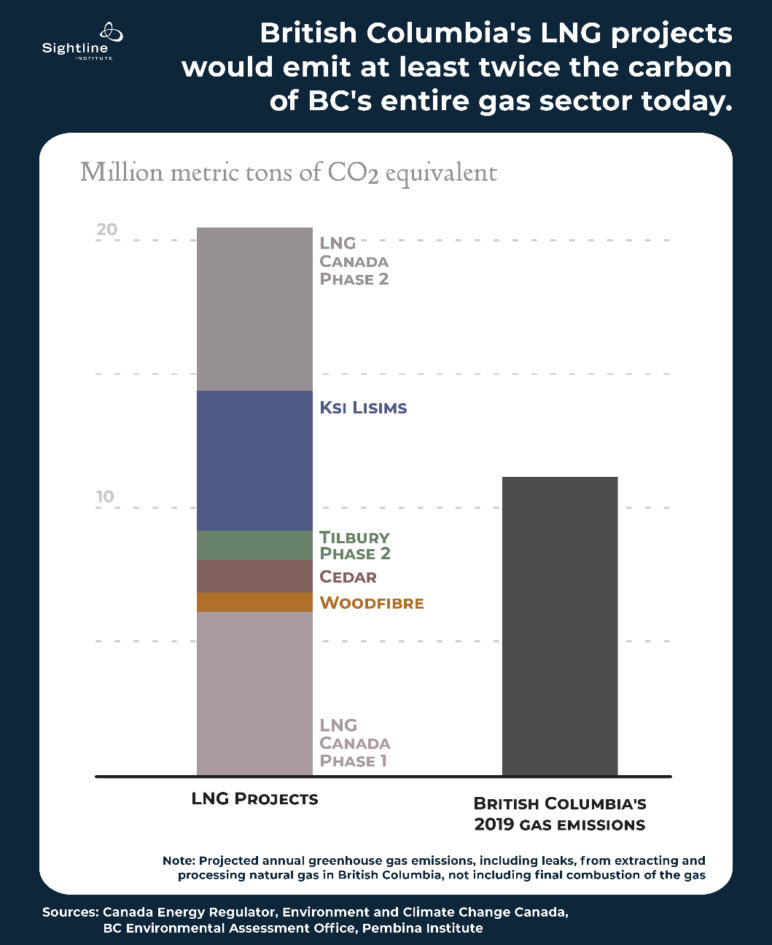

British Columbia is not on track to meet its climate commitments, and building five LNG projects on its shores would only set the province further behind. As of 2019, the year of the last complete assessment, British Columbia’s emissions were rising, not falling, from the baseline 2007 levels. Supplying LNG facilities with gas would require gas companies to drill thousands of new fracked wells in northeastern BC’s Montney’s Formation. But there is no need for new gas fields or export projects developed in a future consistent with the Paris agreement, according to analysis from the IEA. Extracting and liquifying the gas to supply the proposed export facilities—not even burning the gas abroad, just getting it out of the ground and out of the province—would release so much methane and other greenhouse gases that BC’s emissions would increase by at least the equivalent of 20 million metric tons of CO2 by 2030. That’s nearly double today’s current emissions from British Columbia’s gas industry alone, as shown in the chart below.2 Not to mention that each of the LNG export projects either has or is applying for licenses to operate for 30 to 40 years, locking the region into exporting fossil fuels until at least the 2060s, a decade after the world has committed to achieving net zero emissions.

A rocky future for BC’s LNG projects

Despite empty claims that the world needs more Canadian oil and gas, the future is uncertain for BC’s fledgling LNG industry. It may not even be able to rely on the Montney Formation as a source of fracked gas, as it has been expecting. In a June 2021 decision, the BC Supreme Court ruled in favor of the Blueberry River First Nations, whose territory covers most of the Montney Formation. The Blueberry River First Nations sued the Province in 2015, stating that extensive industrial development on their land, including thousands of fracked gas wells, breached their treaty rights to fish, hunt, and trap.

The provincial Supreme Court agreed and issued a requirement for a stronger regulatory framework to recognize and respect treaty rights. As the oil and gas industry insider RBN Energy reported, because of the ruling, “producers may eventually slow and then stop their drilling of new gas wells and gas well completions in the very formation—the Montney—that has been powering Western Canada’s gas growth renaissance for the past decade and that forms the backbone of future supplies for the LNG Canada project.” As of now, the Province and the Blueberry River First Nations have reached an interim agreement to allow the projects authorized before the Supreme Court decision to proceed; the state of future well development in the Montney Formation remains in limbo.

In the meantime, activists are still fighting the remaining LNG export projects in British Columbia. The grassroots organization My Sea to Sky has opposed the Woodfibre proposal for eight years, helping to delay its construction. Scheduled to start in 2018, it still has not begun. And both the Tilbury Phase 2 expansion project and the Cedar LNG project are under environmental review and open for public comment until mid-April. Peter McCartney, a climate campaigner with the Wilderness Committee, is optimistic the projects can be stopped because they are the first that must be approved under BC’s 2018 environmental assessment regulations, which require considering greenhouse gas emissions. As he told Sightline, the Tilbury assessment process can help “make the case against LNG.”

As the EU urgently seeks alternatives to Russian gas, the fossil fuel industry and its backers in Canada are trying to take advantage of the crisis to prop up Canada’s moribund LNG export industry. But by the time the first of British Columbia’s remaining five LNG export proposals are up and running—if they ever reach that stage—the EU plans to have fully released itself from the grips of Russian gas. What’s more, British Columbia will be just five years from its next climate deadline to dramatically cut carbon emissions. Leaders in British Columbia would do well to take their own climate commitments seriously and start looking toward cleaner, greener, and safer future, which cannot include extracting and exporting dirty fracked LNG.

Comments are closed.