This article is part of the series Fairer Elections in Portland

Takeaways

The Charter Commission is still deciding:

How to make the City Council more representative of Portland’s population;

Whether to use a voting system that would more accurately reflect the true values of voters; and

Who should run the day-to-day operations of city government.

Today, Portlanders have an opportunity to weigh in on the options.

NOTE: On March 10, the Charter Commission is hosting unlimited public comment on its process and the reforms they’ve been considering – that’s today! Everyone who signs up will get three minutes to testify to the commission and have their voice heard in this once-in-a-decade public discussion. Community members can sign up here to give spoken testimony this evening or submit written testimony at any time here.

For over a year, Portland’s Charter Commission has listened to public input and researched different reforms to the city’s form of government and election system. The window for thorough public discussion of City Charter reforms like these only opens once a decade, giving the commission a rare chance to make Portland’s government more representative of its diverse city, more accountable to constituents, and more responsive in providing city services.

With these goals in mind, the commission has arrived at three broad agreements and is looking for public input in hashing out the details.

- First, the City Council should have more members, all of whom should represent districts rather than the city as a whole.

- Next, public officials should be elected using a method that only takes one election to yield final results and that captures multiple preferences from voters.

- Finally, councilors should stick to lawmaking and stop stretching themselves thin by also running city agencies.

These proposals are a great start and have real potential to increase community trust in their elected leaders and city staff. They’ll form the backbone of possible ballot measures that voters would consider in November.

But before the commission can send any decisions off to the City Attorney to draft actual ballot measures, they need to resolve some key remaining questions. On Thursday night, the public has one of its last opportunities to weigh in on these and other questions before the Charter Commission sets these proposals in stone. After this month there will only be a few details to tinker with and a simple yes/no vote on the draft proposals. Then it’ll be another 10 years before a new Charter Commission can consider a major change to the organization and selection of Portland’s government.

Question 1: Who gets to be represented on the City Council?

Right now, Portland’s winner-take-all election system means that every seat on the City Council is controlled by the same set of voters: white people, residents of the wealthy west side and inner east side, and homeowners. Most Americans are accustomed to winner-take-all systems, where candidates with the most votes win. But it’s a crude method when used for multi-seat bodies like councils because it allows a bare majority of voters to control all the seats in a governing body. (Indeed, many other developed countries have abandoned winner-take-all election systems or never implemented them in the first place.) Meanwhile, the rest of the voters, who may make up a significant part of the population, have a disproportionately low level of representation. This is a huge part of why people of color, East Portlanders, and renters have been historically underrepresented at City Hall. Winner-take-all elections mean that too many Portlanders don’t have a councilor who understands their concerns, responds to their needs, or represents their opinions during policymaking.

Winner-take-all elections mean that too many Portlanders don’t have a councilor who understands their concerns, responds to their needs, or represents their opinions during policymaking.

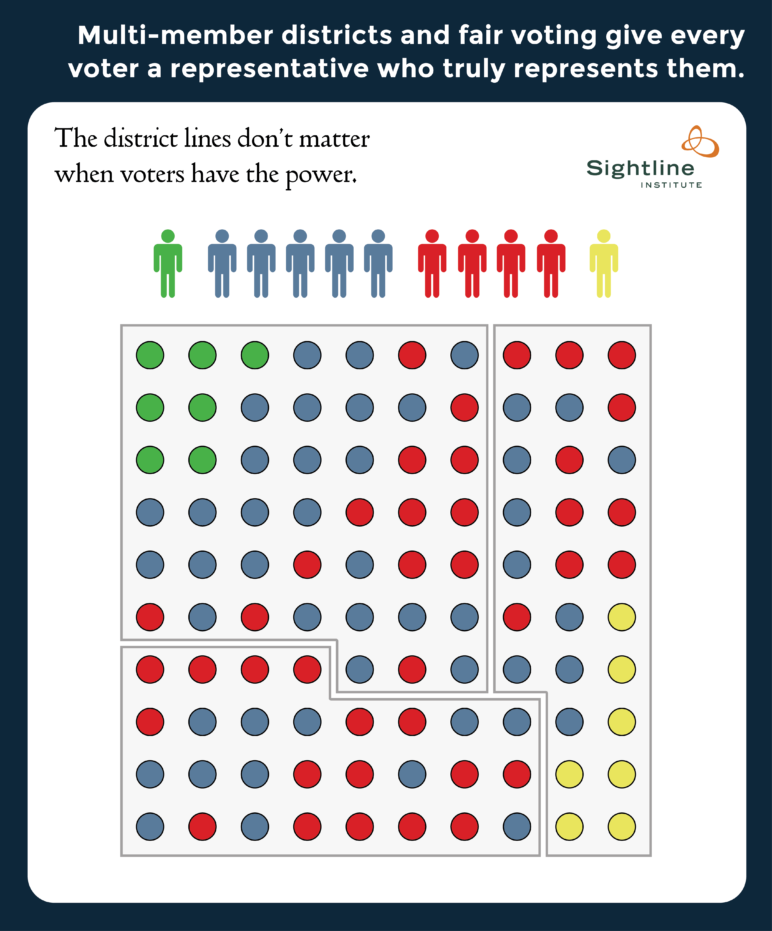

Multi-member districts, which the commission is considering, can elect councilors proportionally to their support in the community. Say that 25 percent of voters in a district support a candidate that speaks to their specific concerns. In a district that elects four councilors, that candidate can win one of the available seats, leaving three for the other 75 percent of voters, instead of being locked out entirely. This satisfies more voters, who can see somebody they actually voted for on the City Council fighting for their issues.

A proportionally elected City Council would look like a microcosm of the political views across the entire city, rather than just amplifying the voices of the same voters over and over again. And the more representatives that we elect from within each district, the better those representatives reflect the true viewpoints of their constituents. It’s impossible for one councilor to represent the broad political spectrum of any district, but a reasonable number, say four or five, would give residents multiple voices to carry their diverse opinions. More councilors from each district would also virtually eliminate the impact of gerrymandering, because voters in the political minority of any district still get to elect candidates in proportion to their share of the population. Unlike single-member districts, it’s extremely hard to gerrymander a multi-member district to lock some voters out of power without increasing their representation in surrounding districts.

The graphic above illustrates these effects. Even though green and yellow voters are in the minority in their districts, they still get to elect one candidate in proportion to their strength. And moving district boundaries around to weaken red voters in one district would just strengthen red voters in another district. Because winner-take-all districts mean candidates with less than 50 percent support get nothing, it’s feasible to shift boundaries around to keep some groups of voters under that 50 percent threshold across several districts. But when voters get to elect candidates proportionally to their levels of support, moving enough blue voters out of one district to remove a blue representative just means that the district next door adds a blue representative—but it’s much harder to keep blue under a threshold of 25 percent or 20 percent across the board. Multi-member districts would mean that voters, not district lines, decide who gets to be on the City Council.

Multi-member districts would mean that voters, not district lines, decide who gets to be on the City Council.

Multi-member districts would give better representation to community members in every corner of the city, meaning that more Portlanders have an elected official they voted for and can trust to champion their concerns on the City Council. By electing more councilors in each district, we can make City Hall more reflective of the diverse political views and communities across Portland.

The commission is also considering single-member districts. But that’s simply another flavor of winner-take-all that would lead to the same outcomes we have now.1 Because communities of color, renters, and other non-majority groups are spread across the city, single-member districts would continue to prevent them from electing candidates of their choice. There might be a chance for one renter-favored candidate if one district is centered around downtown, but renters in the rest of the city wouldn’t have anybody to represent their needs. It’s even worse for people of color, who are spread so evenly across the city that it’s impossible to draw any district where they would make up a majority and be able to elect their candidate of choice. And single-member districts wouldn’t even guarantee fair representation for East Portlanders, who could still be gerrymandered out of the majority in a district by grouping them with wealthier and whiter residents of the inner east side.

Question 2: Which election system lets more Portlanders vote honestly?

Portland’s current election rules have more than their fair share of issues. Sometimes candidates are elected to citywide office despite most voters opposing them. If they want to avoid this, voters have to make strategic calculations about who they think can win instead of just voting for who they honestly want to win. Almost 70 percent of City Council races are decided by a smaller, older, whiter primary electorate before half of voters ever weigh in, which means that councilors don’t represent the entire city and many Portlanders don’t trust them to understand their needs.

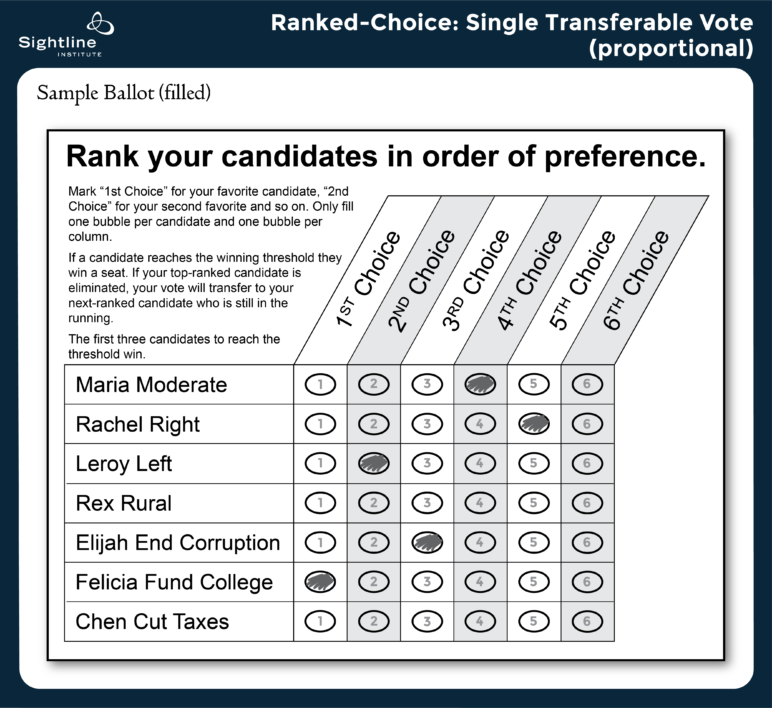

To overcome these issues, the Charter Commission is considering a move to a single election using ranked choice voting. Voters can pick their true favorite first and fill out the rest of the ballot without worrying that they’ll hurt their first choice or that their vote will be “wasted” on a candidate that might not be a strong contender.2 Ranked choice voting can also lead to more civil campaigns, because candidates can benefit from the second- and third-choice votes of their opponents’ supporters. It can also prevent extreme candidates from gaining power, because it stops polarizing candidates from winning a primary or general election in a crowded field where their opposition is divided. And ranked choice voting would let Portland run City Council races in just one election, without having to also use an expensive, low-turnout primary election to narrow down a large field of candidates.

The City Council could actually reflect the diverse views of Portlanders if voters are able to vote honestly for the candidates and policies they want to see in City Hall. And because they aren’t shoehorned into voting for candidates they don’t prefer, voters can actually hold these candidates accountable even if they think the candidates are too popular to lose or the lesser of two evils. Portland could join the 100 places around the country that have already adopted or are moving to ranked choice voting, including Benton County, Oregon, and Alaska.

If the commission does not choose ranked choice voting (RCV), it would likely opt for Score Then Automatic Runoff voting (STAR voting). Unlike RCV, STAR is an untested system with a much lower potential to meaningfully address the flaws in Portland’s elections. Voters are strongly incentivized not to score any other candidates, which would put Portlanders right back in their current pick-one trap. While no voting system is without its flaws, RCV has a clear advantage over STAR for Portlanders because it won’t spiral back down to the current pick-one election system. Maybe further testing will show that STAR can overcome this major issue, but one of America’s major cities isn’t the place to be experimenting with it. Instead, RCV offers voters a proven system that lets them genuinely express their preferences and elect candidates that represent the ideas they want to see in City Hall.

Question 3: If the City Council isn’t running bureaus, who is?

Hundreds of Portlanders have shared with the commission some of the problems with a government where elected officials hold legislative roles while also running city bureaus in the executive branch. Councilors have to split their time between two very different jobs and often lack the expertise necessary for running the bureaus the mayor has assigned them. Frequent shake-ups by the mayor and voters make long-term planning difficult. Voters have few ways to know whether incumbents are doing a good job running a bureau.

These and other issues make Portland’s government less responsive to residents’ concerns, and decrease trust in both the elected officials running the bureaus and the city staffers who do the bureaus’ work. And Portland is out of line with other major cities in the United States: the other 99 of the 100 largest American cities all leave the legislating to a city council and the actual running of the city to a mayor and/or city manager. Portland’s system just doesn’t square with its image as a progressive, example-setting urban center.

The Charter Commission plans to propose a system that would take the day-to-day running of government out of the City Council’s hands. What hasn’t been decided is what Portland’s executive branch could look like. There’s a range of possibilities that assign different powers to the City Council, a mayor elected citywide (or no mayor), and a city manager appointed by the City Council or the Mayor (or no city manager).