Takeaways

After months of threat-backed, mediated negotiation to complete the Private Forest Accord, the Oregon legislature is on the brink of codifying it into law.

New stream buffer protections, plus an array of other rules, would keep salmon streams cool, protect flow, and avoid sedimentation. With luck, the Feds will approve these rules as a 50-year habitat conservation plan for salmon on Oregon’s private forest lands.

For aquatic habitat, Oregon may, finally, catch up with Washington and California.

Still, while the Accord is a huge step forward, it’s a one-trick pony focused on salmon. Especially as climate impacts worsen, stakeholders will need to collaborate further to address logging’s cumulative impacts, protect land-based species and drinking water, mitigate climate change, and move Oregon from piecemeal and process-oriented forest rules to a holistic and outcomes-oriented approach.

Author’s update: In its short session ending on March 9, 2022, the Oregon legislature codified the Private Forest Accord into law. All three associated bills passed with bipartisan support. The new law requires the Oregon Board of Forestry to revise the current Oregon Forest Practice Rules according to the Private Forest Accord Report by November 30, 2022.

Life may soon get easier for Oregon salmon. (And some salamanders and frogs, too.) When it comes to protecting streams and stream-side habitat from logging on private forestland, Oregon could finally catch up with its Cascadian neighbors Washington and California.

What broke the decades-long logjam of inaction? In short, mediated negotiation and cooperation between the timber industry and the conservation community, prodded by the threat of a costly and uncertain fight at the ballot box and new policy that neither side wanted. Governor Kate Brown brokered the discussions and provided a professional mediator, and federal agencies (US Fish & Wildlife and National Marine Fisheries Service) were in the room to support the process.

The resulting Private Forest Accord deal, signed in October 2021, would amend Oregon’s Forest Practices Act to expand riparian buffers, tighten protections against landslides and erosion, support small woodland owners, and improve the rulemaking process going forward—all a long time coming.

The Oregon legislature is considering these protections during the 2022 short session that runs through mid-March. The Accord terms are spread over three separate bills: 1) Senate Bill 1501 implements most provisions of the Private Forest Accord; 2) Senate Bill 1502 compensates small forest landowners with a tax credit; and 3) House Bill 4055 adds a harvest tax to fund ecological mitigation and restoration.

A long lag for Oregon forest rules

For decades, Oregon has not kept up with the Joneses. The Beaver State has lagged well behind its Washington and California neighbors in protecting aquatic and riparian habitat on private forestland, which accounts for over 10 million acres or 34 percent of Oregon’s forests. Federal agencies even denied Oregon $1.2 million in grant funds in 2016 because weak state laws and lax enforcement were allowing logging and road-building to pollute streams, interfere with steady flows, and raise water temperatures above healthy levels for cold-water fish. The media has repeatedly reported on failing forest governance in Oregon, and conservation groups have made many pleas for change.

Oregon’s low forest protection floor translates to over 17 percent less carbon storage per thousand board feet of timber than in Washington, and it increases the opportunity cost of improved forest management, either paid for by public incentives or adopted voluntarily by landowners. Consequently, for example, the percent of forest acres that carry the gold standard Forest Stewardship Council certification (FSC) is roughly eight times greater in California and three times as high in Washington. Green Diamond certifies its California forests under FSC and its Oregon forests under the more lenient Sustainable Forestry Initiative (SFI).

According to Dr. Erin Kelly, professor of forest policy at Humboldt State University, investor-driven TIMOs (Timber Investment Management Organizations) have almost entirely left California because the state’s strict forest protections preempt the high-intensity forest management necessary for breakneck return on investment.

While all three states passed forest practice laws in the early 1970s, Washington and California have substantially revised their laws since then to reflect advances in ecosystem and forest science and to protect forests’ many non-market benefits. Oregon’s laws have evolved, too, but not nearly enough.

In Washington, as with Oregon’s Private Forest Accord, it was also negotiation and cooperation, backed by a legal threat, that modernized forest practice laws. The Boldt court decisions and the resulting collaboration between Washington’s tribes, environmentalists, and timber companies produced a research-based forest law in 1999 that is explicitly designed to protect salmon.

Expanding and strengthening riparian buffers

The centerpiece of the Private Forest Accord deal is new rules for riparian buffers, which are the areas beside streams where logging and other disruptions are banned or restricted. Buffers are critical for stream ecosystem protection. They help prevent erosion, filter out sediment and chemicals, protect streams from intense flooding, provide large wood debris for aquatic habitat, and maintain a cool and moist micro-climate.

Buffers can lower Oregon stream temperatures by up to 7 °C (12.6 °F). This is vital for cold-water fish, such as salmon, as climate change is predicted to raise Oregon’s stream temps by between 1 °C (1.8 °F) and 4 °C (7.2 °F), depending on location. Buffers are also critical for mitigating the more frequent and more extreme heat events, droughts, and floods predicted to accompany Oregon’s rising temperatures, increasing by between 2.6 °C (4.6 °F) and 6.3 °C (11.2 °F)1 by the 2080s.

The new rules would enhance riparian protections in three ways: 1) extend buffer restrictions to previously unprotected categories of streams; 2) increase the size of buffers on all types of streams; and 3) more strictly limit what activities are allowed in buffers.

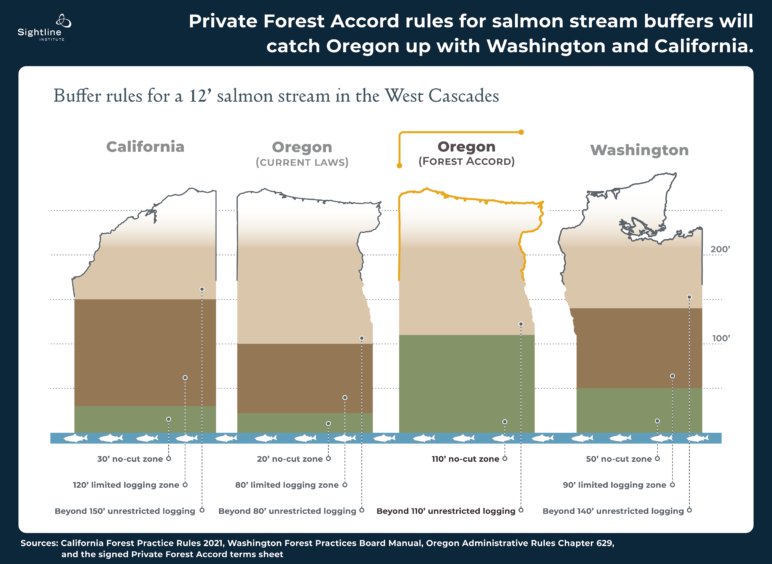

The figure below illustrates an important change: increased buffer protections on streams with fish habitat, including salmon. The second and third bars in the chart show the 450 percent increase in the size of the no-cut zone, between Oregon’s current laws and the proposed Forest Accord laws.

Currently, on streams with fish habitat, including salmon, Oregon’s protections are limited to a narrow no-harvest zone adjacent to the stream and a larger zone where logging is allowed as long as a minimum number of conifer trees are left in place.

For fish streams in western Oregon, the Private Forest Accord rules not only increase the size of the buffer zone from 20 to 110 feet; they also take the unprecedented step of banning logging from the entire zone. Oregon’s new buffers will cover slightly less area than do buffers in California or Washington, but they will be more restrictive.2

A strict no-cut zone is not necessarily better than allowing limited logging, which, when done well, can improve habitat. Negotiators agreed to allow some restoration logging within the no-harvest zone to encourage diverse and healthy forests—for example, thinning monoculture forests, which accelerates old-growth conditions, and reintroducing hardwoods, which provides habitat for beavers and other animals.

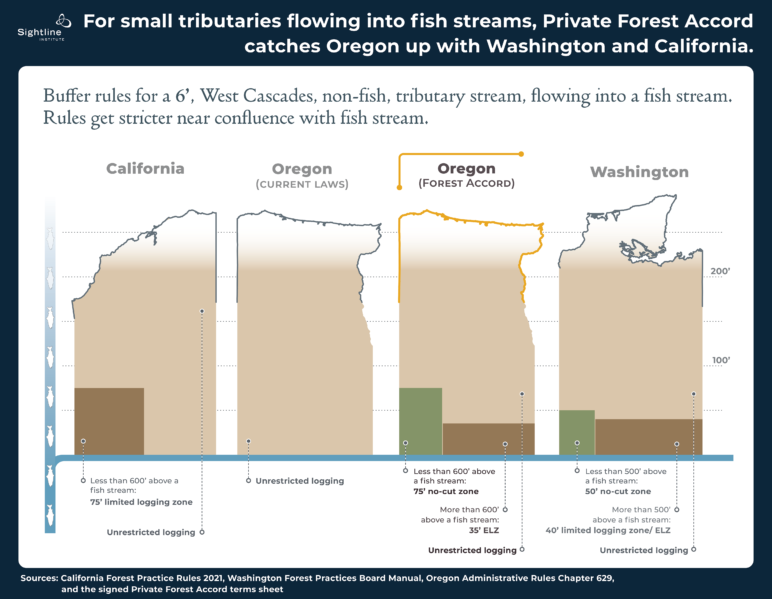

A second figure, below, illustrates an important type of newly protected stream: Oregon’s many small tributary streams that don’t themselves have fish but that flow into streams where fish live. (The rules are slightly different for tributaries that flow into fish streams that host salmon.)

Oregon’s current rules allow logging and heavy equipment right up to the stream bank, where it can expose, disturb, and compact soils (indicated by the uniform tan color in the second bar in the chart). This can stunt tree growth, choke downstream fish habitat with debris and sediment from runoff and erosion, and raise water temperatures.

For years, Washington and California have protected this type of stream with buffers that are stricter near the confluence where tributary streams flow into fish-bearing streams. Northwestern California has a single 75-foot limited logging zone along the tributary stream for 1,000 feet upstream from where it joins a fish-bearing stream. Western Washington has a two-tiered system: a strict no-cut zone around the tributary for 500 feet upstream from its confluence with a fish-bearing stream, and, beyond that, a less strict limited logging zone plus a ban on heavy machinery in an “equipment limitation zone” (ELZ) that requires planting grass, mulching, or otherwise repairing any disturbed soil all along the stream.3

Under the terms of the Private Forest Accord, Oregon would follow this two-tiered model. Tributaries flowing into fish-bearing streams would enjoy a 75-foot no-cut buffer for 600 feet upstream from their confluence. (If the fish stream has salmon, this distance increases to 1,150 feet.) Beyond 600 feet, the rest of the tributary stream is protected by a 35-foot ELZ where, in addition, all shrubs and trees under 6 inches must be retained.

In the chart below, the bottom left corner of each bar marks the confluence where the non-fish stream flows into a fish stream. The Forest Accord’s no-cut buffer, near this confluence, is shown in green.

Each state specifies different rules for their immense array of distinct stream and forest conditions, such as high-elevation ponderosa pine forests on the east side, chronically over-warm streams, or steep banks near springs. These are just two examples that illustrate how, with the Private Forest Accord, Oregon’s buffer rules finally catch up with Washington and California.

Beyond buffers: Landslides, roads, adaptive management, and more

Beyond buffers, negotiators agreed to new logging and road-building restrictions in areas with unstable slopes in order to keep sediment out of streams and to prevent landslides—especially the kind of landslides that crash through stream channels. Other new rules will prevent damage from roads, enhance protections for freshwater springs and for beavers, set up a state- and industry-funded habitat restoration and mitigation program, and establish an outreach program for small forestland owners.

The Private Forest Accord deal also specifies processes for enforcing the rules and for changing the rules if they are not working.

Under the Accord, the Oregon Department of Forestry receives more funding and better direction for compliance and enforcement, and forest owners would be required to allow access for compliance audits. While this addresses a substantial enforcement gap, it falls short of California’s enforcement protocol, which requires pre- and post-harvest inspections for nearly all logging and makes each timber harvest plan public, adding an extra layer of accountability.

The Accord’s adaptive management plan—for monitoring aquatic habitat and fish populations, and adjusting the rules accordingly—improves on Washington’s underperforming plan by relieving a bottleneck within the committee that recommends rule changes. Among other differences, where Washington’s requirement for unanimous consensus empowers just one holdout to prevent needed changes, Oregon will allow stalemates to be broken by supermajority (two-thirds) voting by the Adaptive Management Program Committee (AMPC). However, Oregon’s new protocol, like Washington’s, will not follow the scientific consensus that adaptive management plans should explicitly state what will and will not occur when measured ecological conditions reach pre-identified triggers for decision-making (such as changes in salmon populations).

The deal does not specifically address “cumulative impacts,” a term that refers to the aggregate impacts from land use and landscape features on other parcels in the watershed. These are minimally considered under Oregon statute, whereas California requires a thorough cumulative impacts assessment.

In general, while California’s 431 pages of forest rules do contain specific numerical guides, what’s actually allowed depends—on a case-by-case basis—on whether the harvest activities will achieve environmental quality standards. Before any logging operation can begin, a multi-agency panel must review the Timber Harvest Plan. The California Board of Forestry developed forest law essentially as a guide for complying with stringent state environmental and water standards, resulting in a more holistic and outcomes-based approach, compared with Washington and Oregon’s process-based approaches.

A Habitat Conservation Plan, but no Clean Water Act assurances

Together, if adopted by the state legislature and then approved by federal agencies, Oregon’s new Private Forest Accord rules will constitute a 50-year Habitat Conservation Plan (HCP) for listed salmon and a 25-year HCP for some salamanders and frogs. Federal agencies approved Washington’s forest practice rules as an HCP in 2006. The benefit of an approved HCP is that it grants to landowners and loggers a degree of immunity from prosecution under the Endangered Species Act if they accidently harm endangered animals in the process of otherwise lawful timber harvesting.

Unlike Washington, though, Oregon’s new forest practices rules will not constitute an approved program meeting the requirements of the federal Clean Water Act, as some had hoped. Rural communities in Oregon have spent millions on clean drinking water because forest practice rules don’t adequately protect their watersheds from logging-related pesticides, water shortages, and sediment. Washington negotiators specifically designed their forest practice rules to satisfy Environmental Protection Administration (EPA) water quality protection standards. In exchange, the EPA granted Washington forest waterbodies some immunity from Clean Water Act enforcement, although this arrangement may change if Washington fails to improve its Adaptive Management process and increase protections for non-fish tributary streams.

Beyond salmon, seeing the forest for the trees

Stepping back, it’s important to remember that the Private Forest Accord is a one-issue deal focused on aquatic habitat. For example, while the enhanced riparian buffers will sequester more carbon and increase stream resiliency to climate change, Oregon still needs climate-specific forest rules with specific carbon sequestration targets. The state’s Board of Forestry recently approved a new Climate Change and Carbon Plan, but they have only some of the authority necessary to make bold rules called for by the climate crisis. They need new climate-specific forest laws passed by the legislature to guide their hand.

Additionally, this deal was never meant to address forest harvest and replanting methods that impact broader ecosystem services like land-based habitat, biodiversity, and overall forest health. For example, Oregon will continue to allow clear-cuts that are three to six times bigger than California allows.

Two cheers for (threat-backed) cooperation!

It’s too soon to say whether Oregon’s Private Forest Accord will succeed at protecting endangered aquatic species. The agreement isn’t yet ratified by the state, approved by the federal government, or enforced by state agencies.

Still, the progress so far is a giant step forward for protecting aquatic habitat and restoring the salmon, salamanders, and frogs that depend on it. Some of these amphibious creatures are indicator species that signal an ecosystem’s overall health and act as canaries in the coal mine on looming threats. Salmon, meanwhile, feed forest ecosystems, carrying vital nutrients with them as they migrate from ocean to forest. By protecting these species, Oregonians are restoring and guarding their state’s prized forests.

Ten months of negotiation was a big investment for all of the parties involved in the Private Forest Accord, and it would not have happened without the ballot fight threat and the Governor’s support. Still, the immense progress signals the power of community pressure and regulatory threat to spur negotiation. Cooperation, based in local ecological knowledge—from years of experience studying salmon and forest ecology or building and maintaining logging roads or managing harvests in all kinds of conditions—can prevent excessive red tape for forest owners while protecting the lands and living things that Oregonians treasure.

Note on methods: To construct these figures, Sightline collected into one table all of the buffer rules from states’ statutes and manuals and from the negotiated Private Forest Accord deal signed terms sheet. Sightline then chose representative stream conditions that are most comparable across states. The selection was guided in part by personal communication with forestry professors in all three states, department of forestry personnel, and four MOU signatories.