Takeaways

Alaska’s new open primaries and ranked choice elections in 2022 will require some voter education, and the state’s Division of Elections can’t do it alone.

Fortunately, there are excellent, fun, and free online tools that groups can use to educate their members and even promote their mission or brand…

…All while positioning Alaskans to lead the way to less polarized elections where independents and smaller parties can win representation, too.

Community groups in Alaska working to educate voters face a daunting, but doable, task in 2022. For the first time, Alaskans will use top-four open primaries and ranked choice voting to pick the winners in statewide races. Hundreds of thousands of voters across this vast state will need guidance on the new ways of choosing candidates. Turnout and results will hinge on the quality of the information they’re given. If enough Alaskans like the process, other states may decide to unlock the same opportunities for their voters and strengthen the trust and consensus required for a functional democracy.

Public resources for voter education likely won’t be enough. The Alaska Division of Elections will be a valuable hub of information, but its budget is simply too small to adequately prime every voter for the changes ahead. Nonprofits of all stripes, business groups, neighborhood associations, and others can, and should, help by informing their networks and members about how the new system will work. The political returns could be well worth it for groups that support specific causes or candidates. That’s because voters who are familiar with the new ballots will be far more likely to cast one successfully. Organizations can also generate goodwill for themselves by providing trustworthy information on effective civic engagement. They shouldn’t let lack of experience in voter education hold them back.

Spreading the word about open primaries and ranked choice voting might be as simple as posting a how-to video to a social media account. Other activities might include tabling at the Alaska State Fair, door-knocking in Spenard, or mailing election materials to Savoonga. The approach doesn’t have to be particularly formal. But it does need to be accurate and engaging. Anything a group does to familiarize its members with the new method will help. The mountain biking groups I follow in Anchorage could have members rank the best stretches of singletrack. Or maybe my book club will forgive me for my poor attendance record and set aside some time to discuss our new voting system. Or Hula Hands, my go-to restaurant for Hawaiian food, might run a mock election on its social media asking followers to rank their menu faves.

Whatever form the message takes, it helps to remember that open primaries and ranked choice voting are easy to understand. Rather, change itself is the obstacle (which is maybe why I still sometimes forget to use my rear camera while parallel parking). This article provides some basic tools organizations can use to inform voters, including explainers, videos and other graphics, sample ballots, and mock elections. It also addresses funding and resources for voter outreach and how ranked choice voting education played out for Maine and other early adopters of the system.

Quick recap: Alaska’s new way of voting

Alaskans are switching from party primaries and pick-one voting in the general election to open primaries and ranked choice voting in 2022 because of a citizens’ initiative passed in November 2020. More than 344,000 Alaskans weighed in on what was known as “Ballot Measure 2.”

In the primaries, Alaska’s political parties will no longer hold separate nominating contests. Instead, voters will choose one favorite from a list of all the candidates running for a particular office. The top four candidates in that race, regardless of party affiliation, then advance to the ranked choice general election. Party registration information for each candidate will appear on both the primary and general election ballots. The new system does not prevent parties or other groups from endorsing candidates.

After the top four vote-getters advance to the general, voters will rank them from most to least favorite. Once the polls are closed, everybody’s first-choice vote is counted. If a candidate receives a majority of the first-choice votes (50% plus 1), that candidate is the winner. If no candidate achieves a majority with first-choice votes alone, then the candidate with the fewest first-choice votes is eliminated, and the voters who preferred that candidate have their vote count for their next preference on their ballot. This process will continue until a candidate receives a majority of the vote.

Go heavy on hands-on learning and visuals

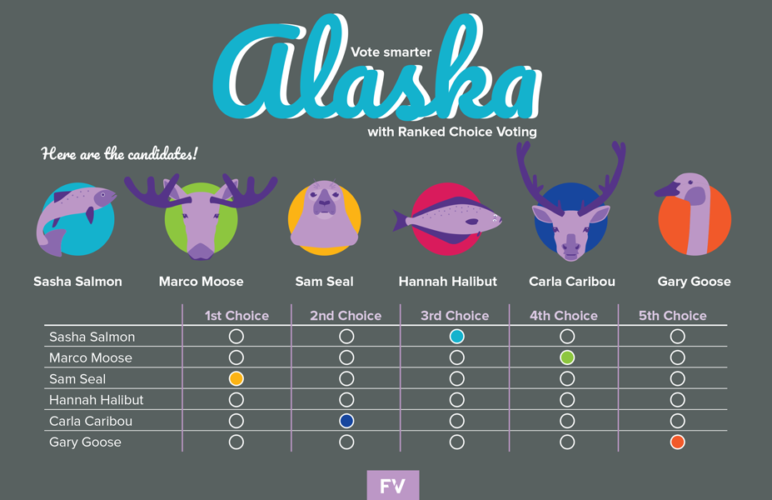

The best way to learn a new board game is to start playing rather than listening to someone drone on about the rules. Likewise, prospective voters should have easy access to sample ballots with clear instructions. Sample ballots can look official, like this one from the Center for Civic Design. Or playful, like this one using Alaska animals. FairVote, a nonpartisan organization with expertise in ranked choice voting, also has real-life examples from jurisdictions in South Carolina, Maine, and Minnesota. And Alaska’s Division of Elections has official sample ballots for the open primary and the ranked choice general election on its website.

Videos are another great way to educate voters. Some show how ranked choice voting can be applied to all sorts of situations, from ordering takeout to picking your favorite color. New York City explains ranked choice voting in less than 90 seconds using strong, simple graphics and clear language. A ranked choice voting cartoon produced by Santa Fe, New Mexico, features adorable woodland creatures and a lizard. Salt Lake City, Utah, uses fruit to explain it. In Maine a video from the League of Women Voters takes a little more time to explain the process, including how couriers move ballots across the state and how votes are tabulated.

Credit: Minnesota Public Radio

Try to reach people in their first language

The quality of translation will also make a huge difference in helping voters feel comfortable with the new ballots. In Alaska, about 16 percent of households speak a language other than English at home, according to the US Census Bureau’s 2019 American Community Survey. The Division of Elections provides voter information in Spanish, Tagalog, and nearly a dozen Alaska Native languages. Community groups, including the Alaska Public Interest Research Group and Native People’s Action, have a great opportunity to apply their election-specific expertise in language translation and outreach.

The big question at this point is whether the resources are available to fund this work. Alaskans involved in translation efforts may find New York City’s language translation resources for its recent ranked choice election helpful.

Give the wonks what they want

A small percentage of voters will insist on immersing themselves in the policy details of the new system. Groups such as the nonpartisan public policy forum Commonwealth North and League of Women Voters of Alaska might point the way down the rabbit hole with links to the Ranked Choice Voting Resource Center, League of Women Voters of Maine, or FairVote. High-information voters may also appreciate articles exploring other ranked choice voting policy questions: What new strategies should campaigns consider in a ranked choice environment? How do you draft ranked choice voting legislation? How exactly do variants, such as multi-winner ranked choice voting, work? What are the best practices for designing a ranked choice ballot?

If that’s not enough, organizations can consider posting links to reports and academic articles on how ranked choice voting has worked in other jurisdictions, such as Australia, Maine, New York City, Santa Fe, and Ireland. And of course, Sightline Institute, where I work as an Alaska-based democracy researcher, has written tens of thousands of words on the subject over many, many years, and has a page of greatest hits on ranked choice voting.

Hold mock elections

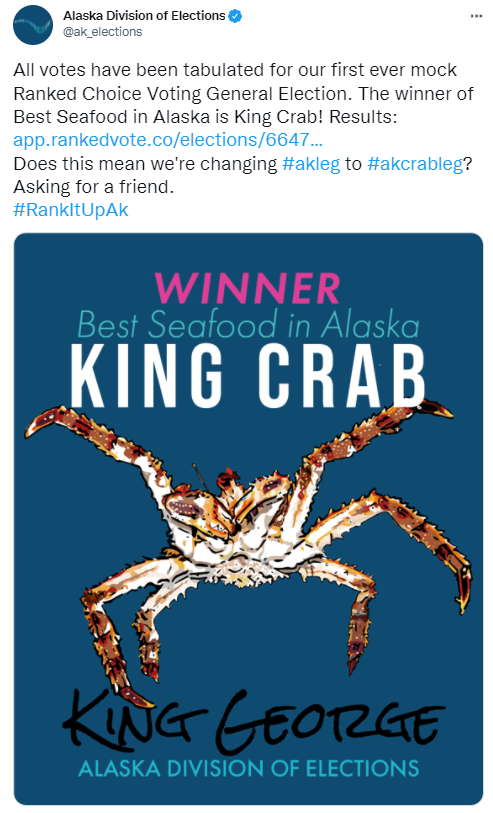

The Alaska Division of Elections held two mock elections on its social media accounts this summer using the new open primary/ranked choice general election format. In June it asked voters to choose the “Best Seafood in Alaska” (winner: king crab). In July it asked, “Which sport is the sportiest sport out of the Summer Olympic sports?” (winner: gymnastics).

The Division will most certainly do more in the lead-up to November. A report by the racial justice organization More Equitable Democracy and other groups found that New York voters “quickly became familiar with the concept of ranking when provided with visual aids. Participants who did not have visual aids felt significantly less confident in their understanding of the voting process, even if ranking itself was easy to understand.”

Alaska organizations and businesses can run their own mock elections as part of branding campaigns or member outreach. The Anchorage Museum might ask visitors to rank their favorite piece in the permanent collection. State agencies might get in on the fun. For example, the state Department of Transportation could ask Alaskans to rank the prettiest stretches of highway in the state (e.g. the Nome-Teller, Seward, and Alaska Marine Highways, plus the eastern stretch of the Glenn).

There’s no shortage of inspiration for mock election topics. Santa Fe, New Mexico, had a ballot for ranking local wildlife. In Utah, where 23 cities opted for ranked choice elections this year, sample races focused on fruit and “pie, because yum.” Rank The Vote NYC held a mock ballot ranking bodega snacks and explained the concept using bagels. Ranked choice ballot generators include Rankit.vote, OpaVote, and RankedVote and are available on FairVote’s site.

Show Alaska voters their IRL candidate options for ranking

Helping voters visualize their options in the races they’ll actually encounter on the ballot is another educational strategy. This op-ed in the New York Times showed voters how to mark their in-real-life ballots based on their personal picks for the New York City mayor’s race in November. If a voter wanted Eric Adams to win and Maya Wiley to lose, the guide showed which bubbles to fill in. It also gave New Yorkers tips for voting their values, with example ballots for helping a woman, a progressive, or a moderate to win office. Strong graphics played an essential role in getting the message across.

“It’s good to anticipate that people will want to see this kind of thing,” said Rob Richie, president and CEO of FairVote and the author of the op-ed. “Everybody needs to have a chance to walk through it and understand it. It’s like a basketball game: you want everyone, no matter which team they’re on, to understand the rules.”

The practice is common in Australia, where political parties pass out “how to vote” pamphlets outside polling places, according to an article published by Cogitatio. In Alaska, local newspapers might consider publishing a similar guide for key races.

How to pull together on voter education

In Maine, the first state to adopt ranked choice voting, community groups amplified the information distributed by the Secretary of State’s office. The League of Women Voters of Maine and the Committee for Ranked Choice Voting were both critical in getting the word out. They didn’t coordinate closely with the state or town clerks, or other groups, and yet voter education efforts in Maine went well, according to a report commissioned by the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation.

“The various RCV education efforts appear to have worked in parallel successfully, as few problems or issues related to voter confusion were reported for either the June or November elections,” the report concluded.

Alaska may be able to outdo Maine by sharing resources, coordinating, and avoiding duplicative efforts. Alaskans for Better Elections (ABE), the nonpartisan organization that was instrumental in winning public support for Ballot Measure 2, is likely the organization best positioned to complement the Division of Elections as a hub of information. ABE plans to post free educational materials on its website that nonprofits, business groups, and local governments can disseminate to their networks, according to executive director Jason Grenn.

National nonprofits specializing in electoral reform, such as Democracy Rising, can also help organize coalitions of community groups and show them how to incorporate ranked choice voting education into the existing get-out-the-vote programs of their individual members. The nonpartisan nonprofit helps states and localities adapt to electoral reform and can advise on media plans, op-eds, and public service announcements, including bus wraps, podcasts, utility bill inserts, and movie theater previews.

Democracy Rising played a key role in the months leading up to the first ranked choice election in Benton County, Oregon. It developed a voter education plan, sent candidate training materials to every campaign, gave voter education training to community groups, compiled a social media toolkit for coalition partners, sent informational mailers to every household, and designed and funded an exit poll to understand voters’ experiences. The poll found that 85 percent of respondents said the ranked-choice ballot was easy to understand.

Overcoming staffing limitations and small budgets

Money spent on passing electoral reform tends to eclipse the amount spent on making sure the changes go smoothly. Case in point: The fight over Ballot Measure 2 attracted at least $7 million in campaign spending, according to reports filed with the Alaska Public Offices Commission. The lion’s share went to supporting the initiative. Resources for an equally comprehensive education campaign that would ensure the new election system succeeds in Alaska have yet to materialize.

“When advocacy campaigns are hot and on the verge of winning, that is when investment comes in. But funding is critical for implementation. Reforms need to be implemented well, and that takes a lot of work,” said Maria Perez, co-director of Democracy Rising. “In terms of resources, jurisdictions and community groups often don’t have much to work with.”

A lawsuit seeking to overturn Ballot Measure 2 may also be giving potential funders pause. The Alaska Independence Party and other plaintiffs have appealed to the Alaska Supreme Court after losing the suit in state Superior Court. The court expects to hear arguments and issue a decision in January. (Note: The Alaska Independence Party seeks to make Alaska independent from the United States and does not represent the majority of independent voters.)

Alaskans for Better Elections has $1.3 million in hand for 2022 operations and expects to ramp up its budget significantly, according to executive director Jason Grenn. In addition to its own voter education efforts, ABE intends to give grants to other Alaska organizations working on voter turnout and education.

The Alaska Division of Elections budget for voter education is just $150,000, part of the $803,000 appropriated to implement Ballot Measure 2. The funding available for voter education could go up or down if other expenses vary from what was estimated, according to the division. In addition to informing its members and networks about normal election housekeeping, like important deadlines and where to vote, the Division will need to help Alaskans understand the new primary and general election ballot formats and how results will be tallied.

A smallish budget also featured in Maine’s effort to educate voters in the lead-up to the state’s first ranked choice elections in 2018. Secretary of State Matthew Dunlap set up a ranked choice voting resource webpage with explainers, sample ballots, FAQs, and an animated video. Dunlap also hosted public forums at libraries in some of the major population centers.

As Alaska goes, so goes the nation?

On election policy, Alaska has proved nimbler than the federal government and every other state but Maine. Through the adoption of open primaries and ranked choice voting, Alaskans have committed to a fairer, more functional process for choosing leaders. But passage of the measure was just the beginning. Now, Alaskans from all backgrounds and political ideologies have the power to shape the follow-through and make it a success.

There’s more at stake than statewide politics. Alaska is on a bipartisan shortlist of recent ranked choice voting converts that includes Maine, New York City, several cities in Utah, and the Virginia Republican Party. Democracy in the United States is becoming a fast-growing wilderness leading millions of Americans astray. The success of these ranked choice systems, including Alaska’s, could help determine how many return to the fold.