Takeaways

Portland has yet to follow years-old council orders to change its parking rules

Neighborhoods that struggle with parking agree: the current process for permits rarely works.

While Portland paused performance-based pricing during the pandemic, Seattle allowed rates to fall with demand.

“Urgent.”

A Portland task force studying how to use pricing tools to make the transportation system more equitable used the word five times in their final recommendations, which are expected to be adopted by city council on October 13th. But is the city up to the task? Side by side with new ideas are ones that somehow keep coming back to city hall every couple years, with few results to show for it.

“We should not slow-walk changes to a system that is perpetuating inequities,” said Ady Leverette, a task force member and former staffer for progressive chamber of commerce Business for a Better Portland. “It’s an unacceptable way to conduct policy.” The report notes that people of color, people living on low incomes, and people with disabilities are disproportionately harmed by Portland’s transportation system through longer travel times, inequitable access to transportation options, increased traffic, and safety risks. Failure to act will only worsen today’s challenges.

Finding the low-hanging fruit

Initially, the task force was convened to develop strategies on how to implement congestion pricing in a way that would be equitable, after city leaders visited London and Stockholm to see it in action. The equity framework the task force proposed came down to a central premise: that pricing tools can reduce disparities in transportation outcomes, provided that people are getting the benefits they are paying for—whether it is free-flowing traffic or usually being able to find a convenient parking spot.

The task force ended up recommending a heap of good policies, from parking cash-outs, to road usage charges with variable pricing to encourage low-emission vehicles or diving at off-peak hours, to recommending the city advocate for abolishing the state’s constitutional restriction on gas tax funds. In total, these policies could reduce competition for road space by nudging people into travelling at different times or different modes, and investing any money generated into walking, biking, and public transit.

“The proposal is super ambitious, and like a lot of plans it sounds great on paper, but only a fraction of what is in a plan will get implemented,” Hau Hagedorn, another task force member, hedged. “If we can get some of those parking policies—which to me is the lower hanging fruit—enacted, that would be a great start.”

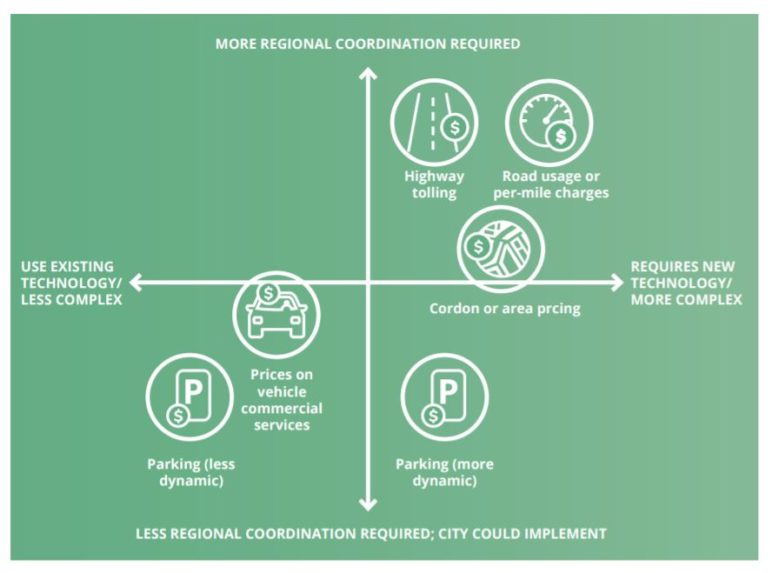

It wasn’t just Hagedorn who thought that. The task force’s final report identified parking management as easiest to implement both in technology and city authority.

There is one issue, though—the city has struggled to implement the tools it already has.

Different year, same parking problems

Take one recommendation: reducing the time and complexity of creating new area parking permit programs. Currently, for any neighborhood to change from totally free parking to a priced permit program, residents who live in the area have to vote 60 percent in favor, with a 50 percent turnout from eligible addresses. Several city commissioners were elected with much smaller margins. In the last week of his term in 2016, Steve Novick proposed a rule change to lower the threshold to a simple 50 percent plus one majority, but the council hearing went sideways and never even went to a vote.

In 2018, city council circled back and authorized the Bureau of Transportation to establish two new area parking permit programs. Out of the nine neighborhoods that requested to participate, none have made it through the process. The Eliot neighborhood, which sits directly north of the Moda Center, came closest. After volunteers went door to door to gather signatures for a petition and then again after ballots went out, the vote came back with 54 percent of households in favor. Not enough. Brad Baker, who organized the effort for the Eliot Neighborhood Association, wasn’t interested in volunteering to try again. “If the pipes are getting too much runoff, it’s not the citizens that have to protest and be like ‘we need to address this,’” Baker said. “The city should do something. It just feels like it’s too much to ask people to do all this work.” Sullivan’s Gulch neighborhood, in between NE Broadway and I-84, has attempted this process three times over the years and has yet to be successful.

The result is that the same commercial streets like SE Division are just as hard to park on today as they were in 2015.

Another recommendation was to accelerate performance based parking pricing, which adjusts meter rates up or down depending on demand, with the goal of always having one or two available spots on each block. City council initially directed the Portland Bureau of Transportation (PBOT) to develop a program in 2016. Two years later, with a new stakeholder advisory committee in agreement, council adopted the Performance Pricing Manual, which defined minimum and maximum hourly rates and recommendations on price changes per year based on demand. But even though the policy exists on paper, nothing has happened on the street.

Today, the cost of this inaction is plain to see.

Both of these areas were difficult to find parking when the policy passed in the spring of 2018—they both still cost $2 per hour, even though demand has returned unevenly.

In the first photo, public streets are sitting unused as the city overcharges for space. In the second photo, pubic parking is scarce as the city charges too little.

The ordinance that was ultimately adopted placed the meter rate changes within Portland’s annual budget cycle which kicks off every spring, but so far it hasn’t been included. Former Commissioner Eudaly remembered that the program was ready to roll out right before COVID but, “there was such a lack of demand for parking after the shutdown, it seemed pointless to implement this policy at the time.” She added, “frankly it was not a top priority in the crisis situation we were in.”

If so, that’s another reason to act quickly now. Demand-priced parking might be a timely boost to downtown retail, while setting the stage for smooth rises once the time is right.

Seattle, which has had been adjusting meter rates annually since 2011, zigged when Portland zagged. As the city re-opened after the initial 2020 COVID surge, all parking meters were set to $0.50 cents per hour, the minimum allowed rate. The Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) evaluated parking demand and adjusted rates in February 2021 and again this past June, and they are planning to collect data quarterly going forward to respond more quickly to changing travel patterns. In a press release, the Seattle Department of Transportation said setting affordable and effective parking rates increases access to businesses and was key to economic recovery. On average, hourly parking rates are still 60-75 percent lower than they were before the pandemic, with the deepest discounts downtown. In all but one parking district, it is cheaper to park than before.

Smart policies, but tough politics

One explanation for why Portland has been slow to move on these types of policies is the political pressure around transportation. Not since Sam Adams won the election for mayor in 2008 has a sitting transportation commissioner gone on to another term, either losing their re-election bid or retiring.

Transportation causes tension in every city, including Seattle. Former Mayor Mike McGinn, who championed performance pricing in Seattle and secured a unanimous vote in favor, never served another term in office, losing campaigns both in 2013 and 2017.

But SDOT acted quickly to get the program on the ground. Data on parking occupancy rates were collected the same month the ordinance was being voted on at city hall, and the first rate changes were on the street within six months. The Seattle Times wrote an op-ed demanding McGinn reverse course, calling the rate changes “too high and too confusing.” But when McGinn left office, his program stayed. Between 2011 and 2019, SDOT made over 300 rate changes based on parking demand, with an equal number going both up and down.

“The status quo has so much inertia,” Leverette explained. But what is considered normal can quickly change. The Portland task force first met around a long table in City Hall in January 2020. Social inequities became even more apparent during the pandemic and motivated the task force to push for urgency, according to Leverette. “One thing that COVID did was show us, very starkly, how it’s possible to make drastic changes if you want to.”

Change is always happening, whether its new housing in your neighborhood or a global pandemic. Tools like parking permits and demand-based pricing can help cities manage those changes proactively, so that we can efficiently adapt to the next wave of change. But until policies are implemented, they can’t help.