This article is part of the series Transitioning From Puget Sound Oil Refineries

The coming decades will bring increasingly volatile oil markets as well as promising boosts in energy efficiency, vehicle electrification, and a shift to cheaper clean energy. As demand for oil drops, Puget Sound refinery communities can plan ahead for a smooth transition—protecting workers, local economies, and the environment to build a thriving and resilient future. This article is part of a special series on the issue.

Thinking too deeply about climate change can be bleak, and it can be hard to imagine what successful climate mitigation might look like. Thankfully, we have an example right in the heart of Seattle: Gasworks Park.

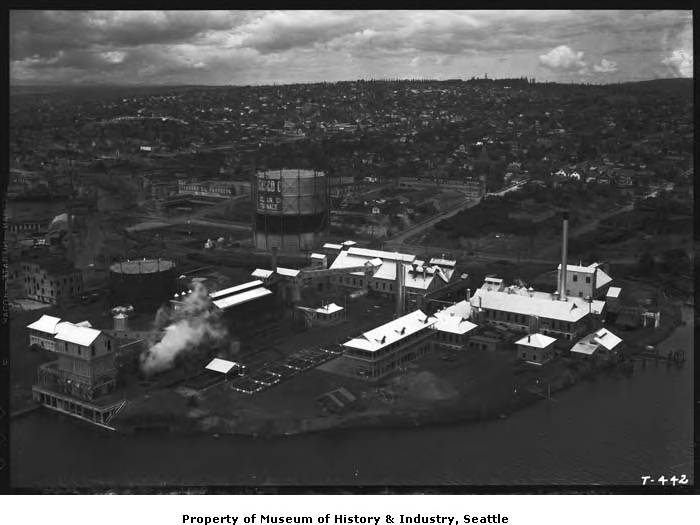

In 1906, the Seattle Gas Light Company built a coal gasification plant1 on the peninsula jutting into Lake Union. Much of the original plant was replaced in 1937 when the plant switched to making gas from petroleum. It closed for good in 1956.

Fifty years of gasification was hard on the land. According to UW historian Thaisa Way, the soil was “totally unproductive. It had char bubbling up; it had oil spills all over it.” The entire site was contaminated by sulfur, arsenic, and coal tar. Intending to demolish the physical structures and create a park, the City of Seattle bought the land in 1962. However, landscape architect Richard Haag proposed keeping some of the industrial buildings and incorporating them into the design of the park. His design was chosen, and eventually the work to detoxify the land began. The transformation took six years and included extensive and pioneering bioremediation techniques. By mixing organic matter with the contaminated dirt, most of the land was detoxified, and the most toxic materials were “put in a large pile and capped with 18 inches of hard-packed clay.” That pile is now known as Kite Hill, a defining feature of the park. The Department of Ecology monitors the park to this day and conducts additional clean up measures as necessary. Gasworks Park finally opened in 1976, twenty years after it ceased its carbon emitting and toxic function.

The story of Gasworks Park is illustrative of the immense opportunity of refinery retirement. In the span of 20 years, Gasworks went from a polluting eyesore to a beautiful community space. This story also illustrates how arduous the transition will be. A gasification plant from 1956 is miniscule compared to the scale of five oil refineries in 2021.

But for a moment, set that aside. Imagine what it will be like if we did it, if we are successful…

It’s 2050 and, though it seemed almost impossible at times, the Northwest actually managed to decarbonize. Step by step, we trimmed our pollution in ways big and small. We converted our buildings from natural gas to clean electricity. Through a next-generation electric grid, solar and wind farms in Washington, Oregon, Idaho, and Montana are connected to population centers west of the Cascades. At the same time, our fleet that was once composed of millions of gasoline- and diesel-powered vehicles gradually but inexorably gave way to new generations of electric cars and trucks. We altered our farming and forestry practices to soak up excess carbon from the atmosphere, and we saw technological breakthroughs that completely reformed industrial manufacturing of things like cement, steel, and glass. Thanks to breathing clearer air, people are healthier. The Salish Sea is less polluted, and the orcas and salmon are thriving.

At least, that’s one way the next 30 years could go.

Of course, there is another scenario too, in which we make only halting progress on achieving our climate goals. In this future, we continue to power our cities and our transportation systems with mostly dirty energy. Annual wildfires grow ever more destructive as our last salmon runs dwindle and once-lavish ecologies like Puget Sound are degraded, acidified, and emptied of life.

No one wants this future. It is, we hope, avoidable.

At the time of this writing, in the summer of 2021, there are signs of both hope and doom. We have the power to choose our climate path.

On the one hand, the International Energy Agency is predicting that 2023 will set new records for global greenhouse gas emissions with no peak in sight. Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau continues to back construction of a large new oil pipeline to the Pacific Coast that is now 30 percent complete. And US oil exports are hitting record highs after the Obama Administration lifted a longstanding ban on the practice.

Yet at the same time, many energy analysts now think that global oil consumption has already peaked and has entered a period of long, slow decline. According to the oil giant BP, total world energy consumption cratered by 4.5 percent in 2020, yet renewable energy capacity grew at the fastest pace ever. The Wall Street Journal is reporting that, “some of the world’s biggest car companies are sending the combustion engine to the scrap heap and are pouring billions of dollars into electric motors and battery factories. Instead of powertrain specialists, they are hiring thousands of software engineers and battery experts.”

In the US Northwest, there are signs that the oil industry is in trouble. After decades of relentless expansion, opponents seem to have fought the industry to a standstill. Apart from the Trans Mountain Pipeline in Canada, the oil industry’s recent expansion schemes in the Northwest have foundered. Plans to build a huge oil-by-rail facility in Vancouver, Washington failed disastrously and probably helped usher in a more progressive local government. So did oil train projects that were proposed for Grays Harbor, Longview, and the Shell refinery at Anacortes. Increasingly, tribes and environmental advocates are looking to further constrain and diminish the industry’s footprint in Cascadia.

In Whatcom County, home of the region’s biggest refineries, the county council recently enacted a set of land use policies that will prohibit new refineries and other fossil fuel developments. Meanwhile, the Tacoma City Council continues to extend a moratorium on new fossil fuel projects in that city. And nearly a half dozen other local governments have banned at least some kinds of oil infrastructure, including Portland, Hoquiam, Vancouver (Washington), and King County.

There is now reason to think that much of the Northwest’s oil industry could be dismantled, including the five refineries that are its biggest financial assets and its most prominent physical manifestation. Washington State passed new legislation in 2021 to reduce the carbon intensity of liquid fuels, over strenuous objections from the oil industry. And the industry’s woes now extend to the private marketplace where investors are increasingly skeptical of oil’s long-term viability. Companies like Shell are looking to radically reduce their holdings of refineries, selling as many as half of them. In fact, Shell sold its only refinery in the Northwest in 2021 for $100 million below its assessed value, perhaps a harbinger of trouble.

Key components of the Northwest oil industry may already be illegal. The two refineries at Anacortes sit on land that may actually belong to the Swinomish Tribe, as delineated in their treaty that is protected by the US Constitution. The Swinomish Tribe is likely to succeed in its lawsuit to stop oil trains from running over its land and the courts have found that the pier for tankers at the BP refinery in Whatcom County was built illegally.

So, there is good reason to believe that the Northwest oil industry will diminish in the coming years. That would mean the reversal of decades of steady growth and it would be unprecedented for a titanic industry that, for more than a century, has become accustomed to getting its way. It is unlikely that Big Oil will go quietly into the night.

The future will be shaped by the plans we make today. The Northwest is moving forward with a decarbonization plan that, if successful, would render the refineries obsolete in their home markets. A transportation sector comprising a fleet of electric cars powered by renewable electricity would almost eliminate oil demand in the Northwest. And if local oil demand disappears, there is no reason for the refineries to exist.

The future for oil is highly uncertain, and there remain many important questions for which there is no public discourse, let alone a well-thought-out plan.

What if the Northwest stops using petroleum products, but the refineries keep running? Would Washington simply become a major fossil fuel exporter, green at home but dirty abroad, much like British Columbia is today? Or, what if the refineries stop refining oil and simply converted into giant export facilities, shipping raw crude oil from North America to foreign markets?

If the refineries do close, how would that work exactly? Refinery workers and tax revenue are undeniably important to local economies, but to date there is no published analysis that even attempts to understand what a transition might look like for these communities. If one or more of the facilities closes, would workers simply be laid-off en masse, a catastrophe for their families and localities? Or could some be employed to cleanup, repurpose, or dismantle the existing infrastructure? If so, what might that look like?

There is a tangle of other questions too. In a future without petroleum, who would pay for toxic cleanup in the Sound, an endeavor now that is largely underwritten by Big Oil? Without refineries, how would county governments manage their diminished property tax rolls?

Our opinion is the refineries should close, and quickly. The imperatives of decarbonization, ecological protection, and longstanding justice all demand a speedy transition to a clean energy future. Whatever causes the refineries to close, whether environmental policy or free market economics or something else entirely, it is vital that Cascadia begins planning for the future.

As far as we know, there is only one serious analysis of what oil refinery retirement could mean, a 2020 study published by Communities for a Better Environment in California. The Northwest deserves something comparable. So, in this series, Sightline will attempt to address many of the major questions about the future of Northwest oil refining.

We acknowledge that many of our answers are incomplete. And, we expect that many in the region will disagree with us or have perspectives that we do not adequately represent. So, it is our strong belief that the right way forward involves serious and systematic planning for what an oil-free Northwest looks like. In our view, that planning should start with the region’s First Peoples and it should include many others: union refinery workers and climate champions; local government officials and environmental justice activists; leaders of the region’s biggest businesses and the kids who will call this region home for the next sixty or seventy years.

We invite you to join the conversation.

Comments are closed.