This article is part of the series Fairer Elections in Portland

Takeaways

In several American cities, more voters have a voice than they do in Portland.

In cities in Minnesota, Michigan, and Massachusetts, voters elect local representatives using proportional voting.

In cities in Minnesota, Michigan, and Massachusetts, voters elect local representatives using proportional voting.

The lower “win number” also allows more—and more diverse—candidates to run for office.

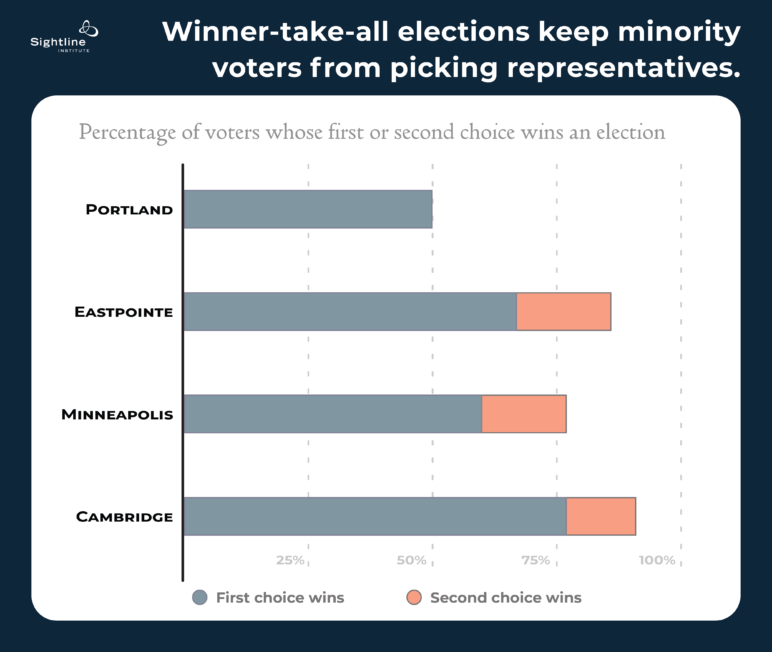

In our last article, we showed how, if Portland used districts, many Portlanders wouldn’t get a candidate of choice on the city council. It doesn’t have to be that way. In several American localities, 80 or 90 percent of voters successfully elect someone they want onto the city council. Rather than using winner-take-all races, where up to half of voters “lose” and don’t have someone representing them in city government, these places use proportional voting, where most voters “win” and have a voice on council.

For Americans who have not experienced proportional voting, the system might sound like magic. Most Americans think of elections like baseball: one team and all its fans win; the others lose. That’s also true of winner-take-all elections. And that’s how it works under Portland’s hundred-year-old system: candidates can choose which seat to run for and, therefore, which candidates they wish to compete against, giving fewer voters a voice. (For example, in May 2020, say a voter’s priority was a candidate with a strong environmental track record. For Position 2, they could vote for either Tera Hurst or Julia DeGraw. Neither won a seat.) Whichever candidate the voter chose, they (and everyone else who voted for the same candidate) ended up without a strong environmental voice on City Council.

Our democracy doesn’t have to have so many losers. Proportional elections are more like ordering pizza; most people are able to get something they like. If Portland expanded the council to 10 members and used proportional ranked choice voting to elect five members every other year, voters would see all the candidates in one pool in November and be able to rank one or more. A voter could rank Tera Hurst first, Julia DeGraw second, and Seth Woolley (who ran for Position 4) third, and stand a good chance that one of them would win one of the five available seats.

It’s not magic. It’s a better way to run elections to ensure that more voters win. Here are a few examples of how this actually works in other American cities.

Eastpointe, Michigan

Eastpointe, a suburb of Detroit, was the first municipality in Michigan to implement ranked-choice voting, either single-winner or multi-winner. While the city’s total population has held relatively stable around 32,000 in the last 20 years, it has transformed from mostly white residents to nearly 50 percent Black residents. Eastpointe went from five percent Black in 2000 to 30 percent Black in 2010 and then 48 percent Black in 2019 and today.

In 2017 Eastpointe elected its first Black council member, Monique Owens, who is now mayor. But local representatives overall did not reflect the city’s rapidly changing demographics. That year, the United States Department of Justice (DOJ) brought a Voting Rights Act lawsuit against the town, alleging that racially polarized voting plus plurality at-large elections for City Council (the same system that Portland currently uses) had prevented Black voters from electing candidates of their choice to City Council. While the DOJ has historically approved districting plans as acceptable fixes to lack of racial representation, Eastpointe leaders felt that a district-based voting system would move the city backwards in terms of racial integration—that rather than sending the message that Black citizens could live anywhere, districts would send the message that Black people would need to live in a “Black district” in order to get political representation. Instead, Eastpointe became the first place in the entire country to move to ranked-choice voting in response to the lawsuit. Filmmaker Grace McNally produced a short documentary about the situation leading up to the lawsuit and how candidates and voters responded to the new voting system.

(Note: Despite its efforts, Eastpointe adopted a two-winner system that is not quite enough to get proportional results. For instance, in a partisan election with two open seats, voters would elect one Democrat and one Republican, even in situations when Republicans outnumber Democrats two-to-one (or vice versa), and voters affiliated with other parties would likely never elect a candidate outside their party. In general, a race needs at least three winners to get fair results, and five winners is ideal. With five winners, any group of voters making up about 18 percent of the population and voting together can get representation.)

Eastpointe held its first multi-winner election in 2019. Selecting among four candidates running for two seats, 67 percent of voters had their first choice elected, and 86 percent of voters had either their first or second choice elected. Setting aside off-cycle voter turnout and whether there was a quality pool of candidates (both important issues but ones that an electoral method alone cannot fix), a system where almost 90 percent of voters get to see one of their top two candidates elected into office is something Portland should aspire to.

Minneapolis, Minnesota

For another example, let’s turn to a city more comparable in size to Portland: Minneapolis, population 430,000. Minneapolis started using ranked choice voting in its 2009 municipal elections and uses the multi-winner form to elect three at-large seats on its nine-member Park and Recreation Board. Since then, 80 percent or more of voters have seen at least one of their top choices elected.

In the last two elections, 10 candidates ran for the three at-large positions. In 2013, 53 percent of voters saw their first choice elected, 74 percent of voters their first or second choices, and 80 percent of voters any of their top three choices. In 2017, 60 percent of voters saw their first choice elected, 77 percent of voters their first or second choices, and 84 percent of voters any of their three choices.

If these candidates had been running in three separate winner-take-all seats in Portland’s system, there would have been three or more candidates in each race. In that system, winner-take-all races could have meant that half or more of voters would have had nothing to show for their effort to cast a ballot (see Portland’s recent mayoral race). But because Minneapolis used proportional ranked voting, four out of five voters elected someone they wanted on the board.

Cambridge, Massachusetts

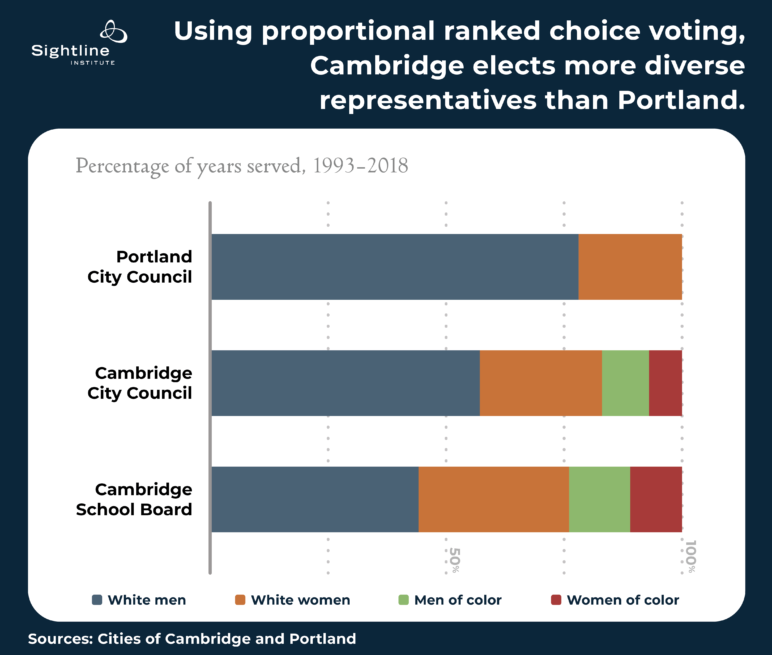

With somewhat similar city demographics, Cambridge has reliably elected more women and people of color than Portland has. Cambridge has the longest-running history of proportional ranked choice voting in the US. During the first half of the 20th century, nearly 30 cities across the country implemented some form of multi-winner proportional representation. In time, all except Cambridge repealed it, mostly in response to minority groups like Black people or Communists actually getting their preferred candidate onto a council. Cambridge stuck with the multi-winner ranked choice system despite several repeal attempts and has consistently elected Black candidates and women to council seats.

Cambridge uses this proportional system to elect nine city councilors and six school committee members—all at-large from the entire city—in November of odd years. Voters consistently see a broad pool of candidates; between 1997 and 2017, an average of 21 candidates ran for the nine council seats in each election. And the vast majority of voters have routinely seen their favorite candidates elected to office. From 1997 to 2017, an average of 77 percent of voters had their first choice elected, 91 percent had their first or second choice elected, and a stunning 95 percent saw one of their top three candidates take office.

Cambridge’s nine-winner race really shows off the potential of a multi-winner system. The threshold to win one of the nine seats is 11 percent of the citywide vote (see next section), which helps explain why Cambridge, which is 10 percent Black, consistently elects Black candidates into office. Under a single-winner system, whether at-large or districts, Black voters would not be able to elect a candidate of their choice in Cambridge unless they preferred the same candidate as voters of other races. Even with single-winner districts, a district would have to be more than half Black for that population to have a candidate of choice elected, which might not even be possible in Cambridge based on where the Black residents live across the city, and in such a district, the system would swamp the votes of Black residents in other districts.

Voters only get one vote each

Some people hear about ranking one, two, or more candidates and think that it means that some voters in Eastpointe and Minneapolis are getting two or more votes each. Not true. Each voter gets just one vote, but the ranked ballot allows officials to, in effect, conduct a primary, general, and runoff all at once, if needed. In other words, if enough candidates win outright after first-choice votes are counted, then the election is over, just like how many Portland elections end when one candidate gets more than 50 percent of the votes in the primary; however, if not enough candidates reach the winning threshold, the ballots automatically move into a runoff, where the less-popular candidates are removed and voters have a chance to choose between the remaining candidates. But ranking allows election officials to just look at the same ballots to see which of the remaining candidates each voter preferred, instead of running a costly second election and dragging out the campaign season. Ranking more than one candidate on one ballot instead of running more than one election where voters can only choose one candidate saves everyone time and money. If a voter only ranks one candidate and that candidate is eliminated, it’s like they only voted in the primary, their candidate got eliminate, and they didn’t like any of the candidates in the general so they sat it out.

Keep Portland weird, but in a good way

Some Portlanders are proud of our unique commissioner form of government. Others are fed up with it and seek an alternative, finding districts with winner-take-all elections to be the more “normal” system that most cities use. Instead of jumping from the pot into the fire, Portland could switch to a different—but proven—election method. Multi-winner proportional elections have a solid track record of giving more voters a say in who gets elected than the mere majority or plurality (less than half) of voters who have a say in the more common winner-take-all elections. Portland already uses winner-take-all elections and has experienced their limitations. Right now, Portland has the chance to become one of a handful of American cities using a method that reliably gives more voters a voice.