This article is part of the series Fairer Elections in Portland

Takeaways

Districting would lead to headaches for Portland.

Portland would likely end up with no more than 33 percent Portlanders of color in any district, and not much more than 10 percent of any specific racial or ethnic group in any district.

Other interest groups wouldn’t get representation, either.

In contrast, proportional voting would achieve fair representation without any risk of gerrymandering.

We previously wrote about how expert redistricters were unable to draw a majority people of color (POC) district in Portland, despite the fact that the city’s population is 28 percent people of color. In some cities, people of color are concentrated in a particular area, allowing districters to draw a line around them. But in Portland, they are spread out. Without intentional racial gerrymandering, districts would have even lower shares of Portlanders of color than the intentionally gerrymandered study showed. And specific racial groups would likely be below 10 percent in most districts.

Districts are far from a panacea for racial representation in Portland. The only kind of representation districts guarantee is geographic, which doesn’t necessarily align with the things that may be important to Portlanders, such as racial identity, housing affordability, or safe streets. In contrast, proportional voting would achieve representation for whatever is important to voters—including geography, if that is what voters want.

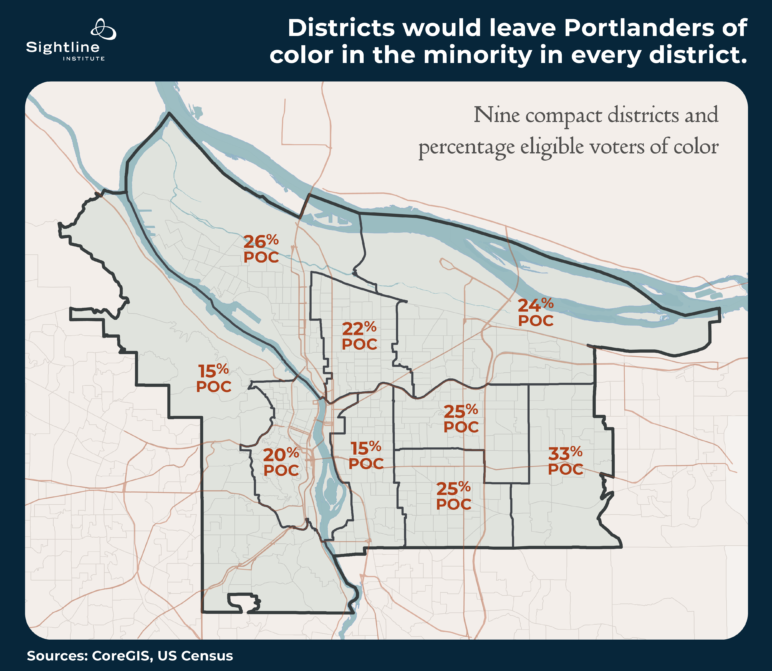

No Portland district would have majority people of color

The districts shown in our last article were sophisticated gerrymanders drawn to maximize concentration of people of color. What would happen if maximizing people of color was not the sole priority of the line drawers? What if the lines were drawn to create compact districts, or to follow major landmarks? The share of Portlanders of color in each compact district would be even lower than the share in districts gerrymandered to maximize Portlanders of color.

For example, the map below is drawn to create compact districts with borders following major arterials, where possible. People of color only make up more than one-third of the voting age citizenry in a single district and make up at most a quarter of the other eight districts.

Interestingly, gerrymandering didn’t move the needle that much in terms of concentrating Portlanders of color. The compact map has one district with 33 percent citizen voting age people of color, and the carefully gerrymandered map maxed out at 36 percent.

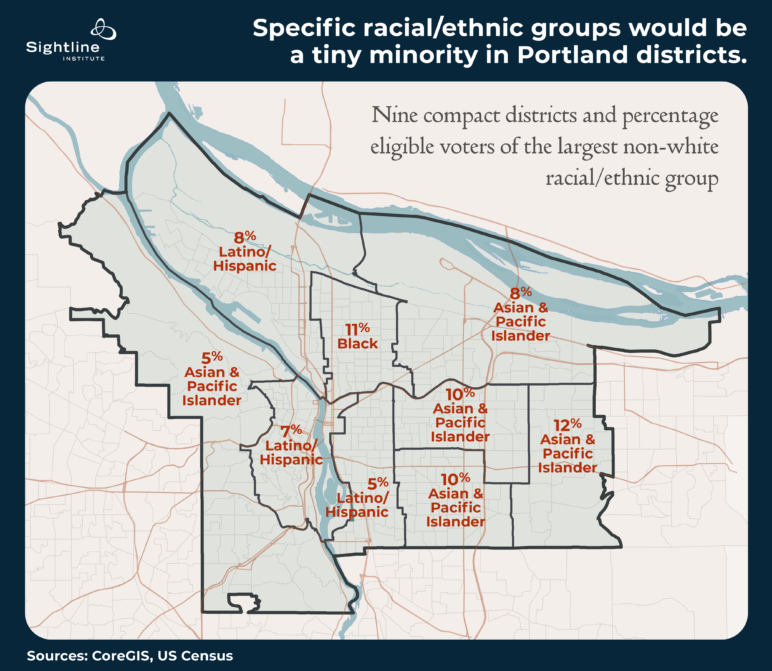

Specific racial and ethnic groups would likely only reach 10 percent in a few districts

Specific racial and ethnic groups would likely only reach 10 percent in a few districts

Second, those districts grouped all Portlanders of color together as a single voting bloc. But in most Voting Rights Act cases, districts are drawn around a single racial or ethnic group. In other places, a district drawn to maximize the voting power of a minority group might be majority Black or majority Hispanic, not grouping together all Black, Asian, Pacific Islander, Native American, Hispanic, and multi-racial voters and treating them like a single group, as the redistricting researchers did for Portland. But these are very diverse groups, and they may or may not have that much in common when it comes to electing a city councilor. Even within any one of these racial or ethnic groups there is a diversity of opinions and experiences. What do districts look like for individual racial or ethnic groups in Portland?

As the map below shows, the largest racial/ethnic group in each hypothetical compact district would be very small.

Redistricting requires headaches

Redistricting requires headaches

The differences between the maps from the last article and this one also highlight the inherent headaches of drawing districts. As we are seeing right now at the state level in Oregon, redistricting is a contentious process because the lines can determine the winners. What type of winner should the line-drawers try to produce? If Portland adopts districts, it will need to create its own redistricting process that will surely be hotly contested. Who will draw the lines? By what criteria? Who will be happy with the results, and who will feel slighted?

Proportional is better

Proportional voting would result in fair representation for more Portlanders, and less redistricting headaches. Housing advocates, street repair enthusiasts, young people, and/or people of color could unite behind a candidate of choice no matter where they live. Voters east of 82nd Avenue could also unite behind one or more candidates and get them elected with a proportional system. And Portland could skip the redistricting headache altogether, electing candidates from a citywide pool.