This article is part of the series Fairer Elections in Portland

Takeaways

A nationally-renowned redistricting group found that it is impossible to draw single-winner districts that would reliably allow Portlanders of color to elect candidates of choice to the city council.

Single-winner districts won’t help voters of color get representation on the Portland City Council.

However, multi-winner races with proportional ranked choice voting would.

City-wide proportional elections, or three districts with three winners each and proportional voting, both would give voters of color a voice on council.

Anyone who has been following analyses of gerrymandering recently has heard the name Moon Duchin. The professor of mathematics at Tufts University leads the MGGG Redistricting Lab (an outgrowth of the Metric Geometry and Gerrymandering Group), a Tufts-based group using cutting-edge research to better understand political districts and their consequences. That group recently analyzed several jurisdictions around the country, including Portland, Oregon, to show how different districting options and voting methods could change voters of colors’ chances of electing candidates of choice.

This thorough analysis from a nationally-acclaimed research group is particularly timely as the Portland Charter Commission considers whether the city should make changes to how we elect city councilors and to our form of government. Right now, we elect four commissioners and one mayor in at-large elections, and each serves as both lawmaker and head of one or more city bureaus.

The MGGG report’s implications are crystal clear: dividing Portland into single-winner districts will not allow voters of color to reliably elect any candidates of choice.

The MGGG report’s implications are crystal clear: dividing Portland into single-winner districts will not allow voters of color to reliably elect any candidates of choice. Even if Portland expands the council to nine members, each elected by district. Even with the most innovative redistricting technology razer-focused on drawing districts to concentrate voters of color and voters of color all throwing their support behind particular candidates. The modelers found zero scenarios in which single-winner districts would reliably give voters of color a candidate of choice. Portlanders of color are simply spread too far across the city to create any geographic district that is not majority white.

But wait! There is good news. Voters of color would be guaranteed a fair shot at electing councilors of choice if Portland were to adopt multi-winner council races with proportional ranked choice voting. The modeling was about people of color, but the results apply to Portlanders who are in the minority for any number of reasons: small business owners, people who are dependent on transit, those who get around by bike, youth, or parents of school-age children. Most groups don’t all live in just one part of the city, so districts might not help them have a voice, but proportional voting would.

Charter Commission members and advocates who care about better representation on city council—whether for Portlanders of color, or for any other class of under-represented Portlanders—would do well to look to multi-winner races and proportional voting, not single-winner districts.

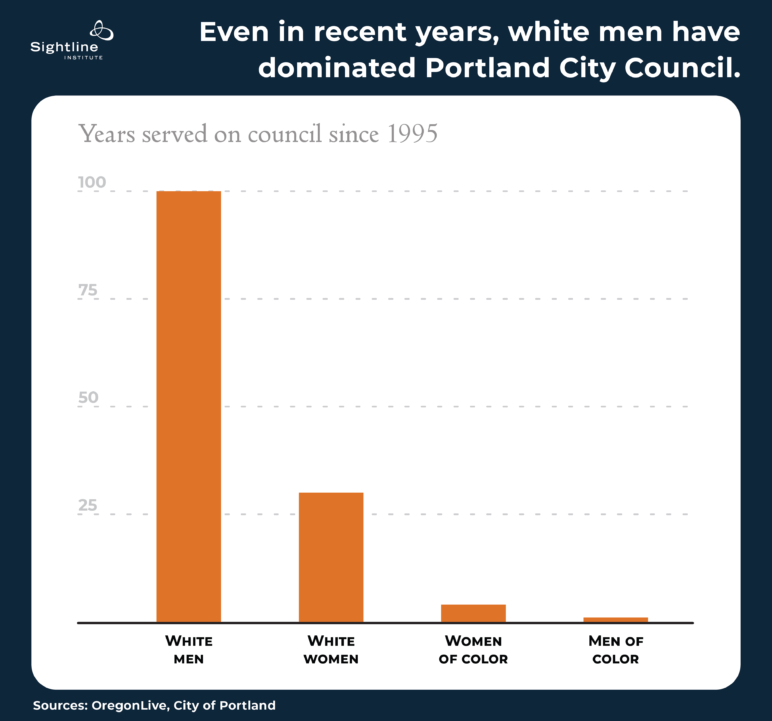

White men are over-represented on Portland City Council, even in recent years

Someone looking only at the current city council might wonder what the problem is. But though the council at this moment is racially and ethnically diverse, that has rarely been the case. We don’t have to look too far back to see how our system has failed to elect representative councils. Looking back since 1995, we see that three-quarters of those serving on council have been white men and less than four percent by people of color, despite the fact that Portland has been at least one-quarter people of color during that period. Some Portlanders have hoped that districts would create a more representative council.

Single-winner, at-large, proportional, Oh My!

Many Americans only know about winner-take-all elections. These can be at-large seats or districted seats, but each race in such an election has a single winner. Portland uses winner-take-all at-large seats: council seats are citywide but are labeled Position 1 through 4, and only a single candidate wins for each position. Eugene and other cities use a winner-take-all district model in which the city is geographically divided into districts (a.k.a. wards), and each one elects a single candidate.

Although it is less well known, more than a hundred American localities use multi-winner elections, some citywide and some in districts. Instead of a single winner per race, candidates run in a larger pool, and the top few (usually between three and seven) win seats. Combined with a proportional form of voting, multi-winner elections result in a more diverse delegation than do single-winner elections.

Cities can choose between citywide or district elections and between single-winner or multi-winner races.

| Citywide | Districts | |

|---|---|---|

| Single-winner (winner-take-all) | Divide the council into numbered positions. Candidates can choose which position to run for, and each voter casts a separate vote for each position. One candidate wins per numbered position. | Divide the city into districts. Candidates must live in the district they run in. Each district elects one councilor. |

| Multi-winner (proportional) | All candidates run citywide in a single pool. The top five, seven, or nine get elected. | Divide the city into districts. Candidates in each district run in a single pool, and the top three candidates from each district win seats. |

MGGG’s results

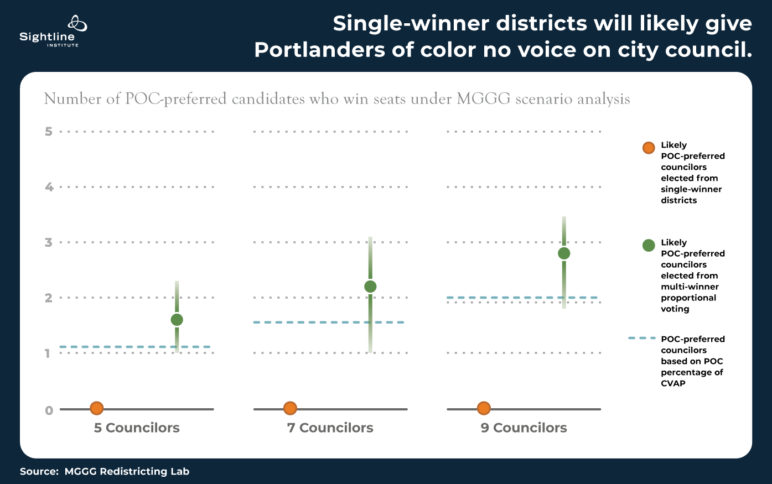

The chart below shows MGGG’s findings for a five, seven, and nine-member council. The orange dots show their conclusion that single-winner districts would result in zero Portlanders-of-color-preferred candidates, every time. But the green dots show that voters of color would likely get at least their fair share of councilors relative to their share of voting age population, shown by the blue dotted line. The fading green bars show the range of their predictions.

Terminology

POC = Portlanders of color. The researchers define Portlanders of color as those who identified on the census as Latino/Hispanic, Asian, Black, or Other (that is, anything other than White and non-Hispanic). Data from the 2020 census is not yet available, so they use the most recent available data, which is from the 2018 American Community Survey five-year rolling average.

CVAP = Citizen voting age Portlanders. That is, Portlanders who are eligible to vote because there are citizens aged 18 or older.

POC-preferred candidate = a candidate that most Portlanders of color preferred over other candidates. The candidate may or may not be a person of color themselves, but they are someone who reflected the values and life experience of enough voters of color to make them someone those voters wanted to represent them in city hall.

Now, here’s how MGGG reached the conclusion that single-winner districts would not help Portlanders of color voters elect preferred candidates, but multi-winner proportional voting would.

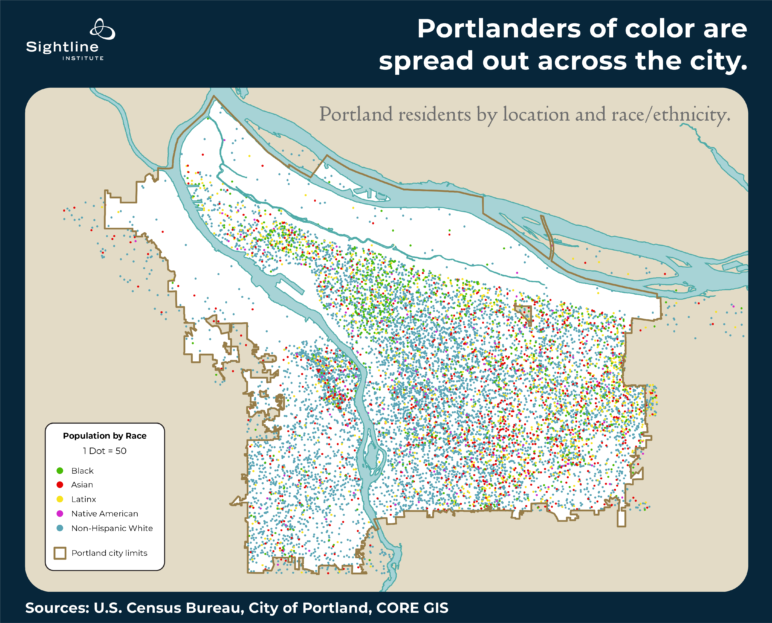

Districts drawn to maximize POC representation

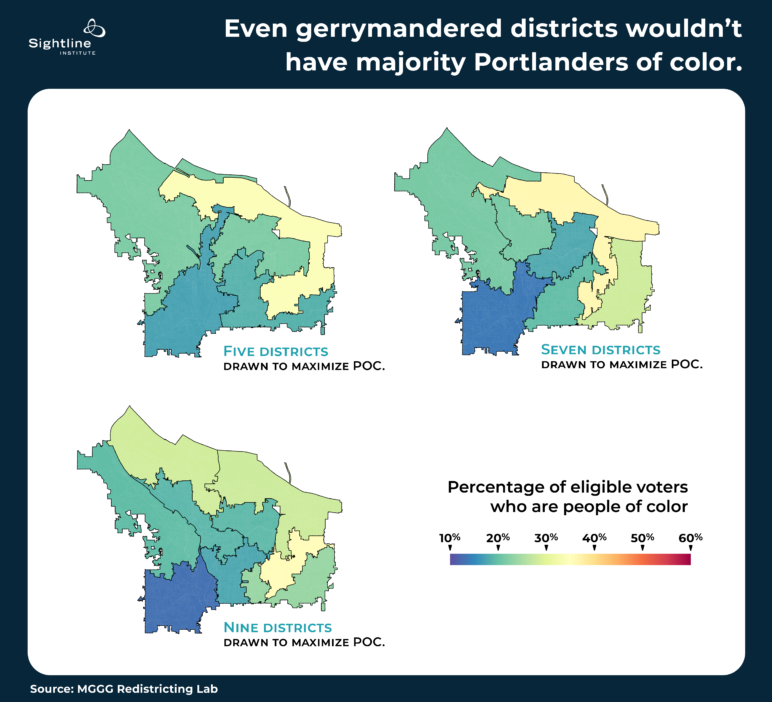

First, the researchers used their redistricting technology to draw Portland districts that maximize the percentage of voters of color. Using a statistical technique that generates possible districts, they tried their best to gerrymander district lines to put as many people of color as possible into the same district. Black, Asian, Latinx, and Native American Portlanders are spread out across the city (see map below), so the researchers were trying to draw district lines that grouped them together as much as possible.

The program created the district maps below. The results were the five-district, seven-district, and nine-district maps below. Blue districts have 15 percent or fewer eligible voters of color, green districts have around 20 percent and yellow around 30 percent. Despite their best efforts, they couldn’t draw a single district with more than 40 percent (orange) or 50 percent (red) people of color. The best they could do was a little more than one-third Portlanders of color in one district per map. The very highest percentage Portlanders of color that their algorithms could draw was one district in the seven-district map stretching across the northeast part of the city and down the Interstate 205 corridor, which just topped 36 percent.

In a single-winner election with two candidates (and no write-ins), a candidate must win more than 50 percent. Portlanders of color make up about 22 percent of the citizen voting age population overall. They are more concentrated on the east and north ends of the city (the more yellow districts, above, have more than 30 percent Portlanders of color) than in the southwest corner of the city (the blue districts above have more than 80 percent White Portlanders). But they are sufficiently spread out across the north and east sides that they don’t come close to the 50 percent threshold to guarantee they can elect a candidate of choice in a single-winner district.

Voters of color most likely elect zero candidates of choice if Portland moves to single-winner districts

If Portland were to adopt single-winner districts for a five-, seven- or nine-member council, it is unlikely that voters of color anywhere in the city could reliably elect a candidate of choice. The researchers concluded that the most likely result would be that candidates preferred by white voters would sweep all the council seats, all the time. Even if the districts were drawn with the express purpose of grouping Portlanders of color voters into certain districts, no district could get close to the 50 percent threshold to win a single-winner seat.

And that’s not even taking into account the possibility that, over time, Portlanders of color voters could move to other parts of the city, making moot the districts that were so carefully drawn to group them together. Portland’s ongoing displacement of residents of color has pushed many out of their historical neighborhoods, or out of the city altogether. Or, whoever draws Portland’s districts might not prioritize keeping Portlanders of color voters together above all other considerations, as the researchers did with the maps above. Or that Portlanders of color voters, seeing the writing on the wall, might not turn out to vote at the same rates that white voters do.

The MGGG report concludes:

Ultimately, we expect traditional districted systems with 5, 7 or 9-member councils to be unlikely to reliably secure POC-representation on the council.

To be clear, this doesn’t mean that no candidates of color will ever be elected to the council. People of color are not monolithic, and our current council shows that candidates of color can win over a majority of voters. What it means is that when people of color have a candidate they prefer because that candidate reflects their values and experiences, whether that person is of their same race or ethnicity or not, those voters will be diluted across districts and will not have the power in any single district to elect their preferred candidate without support for that candidate from white voters.

Multi-winner proportional races are different

After that disappointing districting result, MGGG moved to modeling a different option for obtaining representation for Portlanders of color voters: multi-winner races using proportional ranked choice voting. That is, voters rank candidates in order of preference, and the top three, five, seven, or nine candidates win seats on the council.

In the current at-large system, each candidate for Portland City Council picks a seat to run for citywide. By picking their post, candidates are, to some extent, picking their competition. For example, when an incumbent such as Nick Fish runs, few challengers run against them. After falling short in a 2002 special election for a midterm vacancy and a 2004 general election (the only November election he ever faced, in which he received more votes than in any of his primary victories and still lost to Sam Adams), Fish won election to council by winning a majority in the smaller turnout primaries in 2008, 2010, 2014, and 2018. No challenger received more than one-third of the vote.

But in 2020, there were two open seats (that is, no incumbent in the race) because Fish tragically passed away, and Amanda Fritz chose not to run, opening up Positions 1 and 2. Additionally, incumbent Commissioner Chloe Eudaly (Position 4) and Mayor Ted Wheeler were up for reelection. A total of 54 hopefuls had four races to choose from and strategically chose the seat where they thought the competition most favorable. In the end, 18 candidates chose to run for Fish’s position, nine for Fritz’s, seven against commissioner Chloe Eudaly, and 18 against Mayor Ted Wheeler. Whichever race they chose, each candidate needed to win over the same majority of voters. This is around 150,000 voters in a November election, though seats which get filled in the low-turnout primary might see a candidate win with as few as 75,000 votes—if a candidate wins over 50 percent of the vote in a primary, they are immediately elected without going in front of the larger group of general election voters. The at-large system means the same 150,000 voters citywide (or even less, if they win a majority in a low-turnout primary election) can elect 100 percent of the council seats, while all voters in the minority end up with none.

With single-winner districts, the city could get carved up, and candidates wouldn’t be able to pick the seat to run for—they’d have to run for the district they live in. And they would only need to win a majority of votes in their district, not citywide. If Portland broke up into five districts, candidates would need to win around 30,000 votes from a specific area of the city to win a district election in November. In some places in the United States, districts can be drawn such that voters of color are in the majority in at least one district, giving them the chance to elect a candidate of choice from that district. Of course, voters of color outside that district are left without the option to elect a candidate of choice to their council. But MGGG’s analysis shows that, because Portlanders of color are not sufficiently concentrated in any one area of the city, even this is not possible in Portland. Due to the way Portlanders of color voters are spread around the city, they would be in the minority in every district, so their candidates of choice could still get locked out of council entirely even if the city moved to district-based elections.

Some Oregon cities, such as Lake Oswego, have multi-winner races but don’t use a proportional voting method. All candidates run in a single pool, every voter has three votes, and the three candidates with the most votes win. While candidates don’t get to pick the seat they run for, this still leads to the same big problem the at-large system has: if the majority of voters all like the same three candidates, they will sweep the elections, and voters in the minority will get no voice on council.

Multi-winner races with a proportional voting method are different. They allow voters to elect candidates in proportion to their share of the voters. In a five-winner race, all candidates would run against each other in the same pool, rather than strategically picking their race. If about 50,000 voters from anywhere in the city prefer a particular kind of candidate, then they can elect one of the five winners. That could be any bloc of voters—maybe they want a candidate who champions racial equity, or housing affordability, or attention to investments east of 82nd, or the interests of small business owners. Candidates championing those causes could appeal to their voters, and if there are 50,000 of them, and they rank the candidates with that platform, one of their preferred candidates will win. MGGG modeled preferences of voters of color to show how this works, but it could be the preferences of any other minority bloc of voters. Proportional ranked choice voting lets voters in the minority win a fair minority of seats.

Proportional ranked choice voting would give Portlanders of color a voice on council

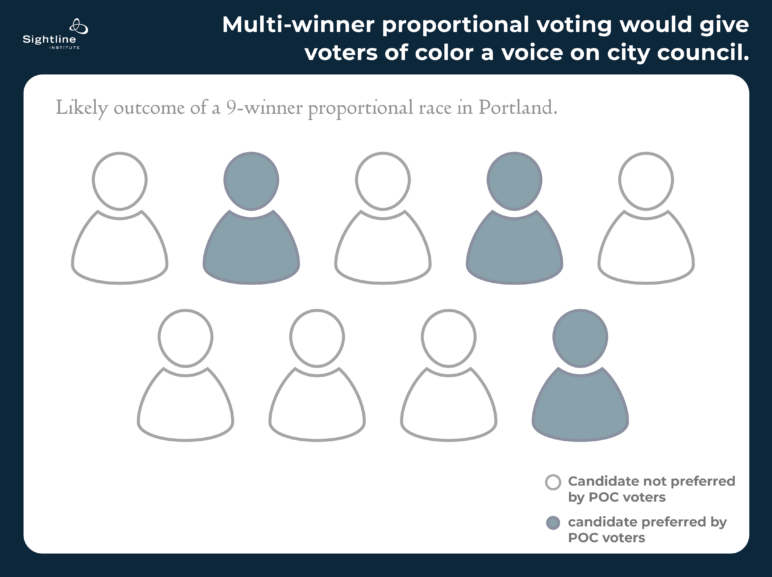

If city councilors were to run in a citywide multi-winner race with five, seven, or nine councilors, using proportional ranked choice voting would give Portlanders of color voters a voice no matter which way you slice it.

Citizen voting age Portlanders of color make up 22 percent of Portlanders. If they elected exactly 22 percent of the council, that would be 1.1 out of five seats, 1.6 out of seven, or 2 out of nine. The MGGG scenarios predicted that, on average, proportional ranked choice voting would allow voters of color to elect 1.6 out of five, 2.2 out of seven, or 2.8 out of nine seats. That’s a far cry from the big fat zero they expect with single-winner districts.

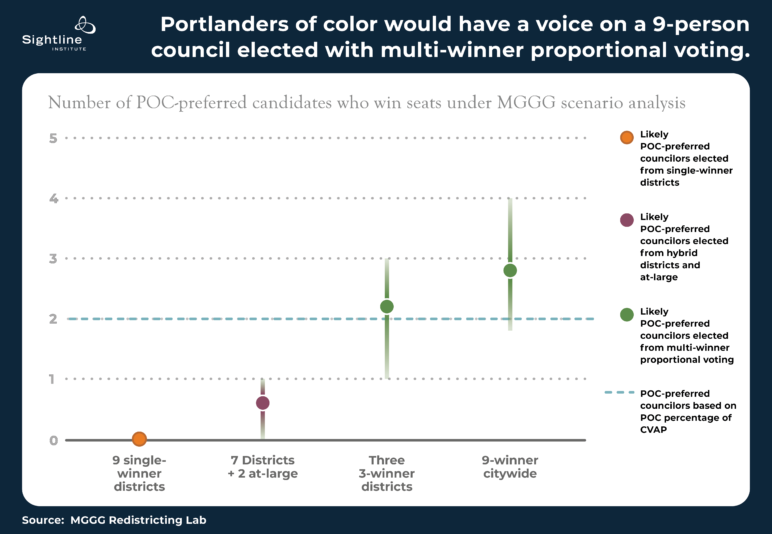

The chart below shows the results of all the scenarios MGGG ran for a nine-member council, where the fair share of Portlanders-of-color-preferred councilors would be two out of nine. The dots show the average expected councilors of choice elected by Portlanders of color voters—orange for single-winner districts, purple for hybrid, and green for proportional systems. The tails extend up and down to the 5th and 95th percentiles of all scenarios run to indicate the possible variations (that is, they cover the middle 90% of likely outcomes).

Note that the researchers didn’t assume they know how voters would behave – they modeled a variety of ways that Portlanders of color and white Portlanders might overlap or diverge in their candidate preferences. The confidence bars below show the results of different assumptions about voter behavior. Even in the most pessimistic scenarios where Portlanders of color are at the greatest disadvantage or have the most divergent preferences relative to white Portlander, voters of color would still be able to put at least one candidate of choice on the council. The dotted blue line shows the percentage of Portland’s citizen voting age population that is Portlanders of color. These voters get a fair voice on council in almost every multi-winner scenario, and much less than a fair voice in the two scenarios that use single-winner districts.

Hybrid single-winner districts plus at-large seats isn’t great

MGGG researchers also looked at a hybrid model: seven councilors elected by single-winner district and two at-large (purple dot and confidence bars in the chart above). This is the system Seattle voters adopted in a 2013 ballot initiative. While this would be a bit better than nine single-winner districts for Portlanders of color, it still runs a strong risk of preventing voters of color from electing a candidate of choice.

Geography isn’t everything

Portlanders see that the city council has historically not represented women and people of color, nor renters, lower-income people, nor those living in the eastern part of the city. Many have concluded, as City Club of Portland did in its 2019 report, that at-large elections bias the system towards unfair representation. Some have concluded that using single-winner districts or wards to ensure councilors come from different parts of the city is a panacea.

Single-winner districts only guarantee geographical representation. MGGG’s analysis proves that, in Portland, geography is not the same as race and ethnicity.

But single-winner districts only guarantee geographical representation. MGGG’s analysis proves that, in Portland, geography is not the same as race and ethnicity. Voters of color won’t have any more power in single-winner districts than they do in Portland’s winner-take-all at-large elections.

The report’s results hold true for other types of minority representation, too. Voters who prefer a champion for renters are in the minority, but because there isn’t a part of the city where all the renters live, districts won’t help. Same for people who are dependent on transit, those who get around by bike, youth, or parents of school-age children. Again, many issues of importance to Portlanders are not determined by geography. Proportional ranked choice voting allows voters to come together and support a candidate of choice based on what is important to them, no matter where they live within the city. If one-fifth of voters prefer a renters’ platform, proportional ranked choice voting will give them the power to elect at least one councilor out of five who will champion renters.

Portland has been proud of its “weird” adherence to the commission system with at-large council positions. We shouldn’t stick with it just because it is different, but we also shouldn’t move to districts just because that’s what everyone else is doing. We can retain Portland’s unique character while also enacting our values of diversity and fair representation, by adopting multi-winner proportional ranked choice voting.

What you can do

The Charter Commission is meeting regularly and welcoming feedback from Portlanders. You can go here to see how to get involved, from participating in meetings to submitting written feedback to commissioners. If you want them to consider options that are more likely to give all Portlanders a voice on council, urge them to consider multi-winner proportional voting options.