This article is part of the series Transitioning From Puget Sound Oil Refineries

Takeaways

The refineries were built on the ancestral land of the Lummi, Swinomish, and Puyallup peoples.

Four refineries were built between 1954 and 1957, with a combined refining capacity of 140,000 barrels per day by 1958.

Four refineries were built between 1954 and 1957, with a combined refining capacity of 140,000 barrels per day by 1958.

Ninety percent of all crude refined in Washington in 2003 was from Alaska.

By 2017, 35 percent of crude oil refined in Washington came from Alaska, 34 percent from Alberta, 24 percent from North Dakota, and 8 percent from other sources.

The authors of this series, two white people born and raised in Washington State, are direct beneficiaries of the United States’ enduring colonial legacy. The Coast Salish peoples and their land were colonized starting in the mid-1800’s. The history of the Pacific Northwest’s refining industry is inextricably linked to the broader history of stealing land through colonization. We have tried, throughout the research and writing process of this and the other chapters in this series, to consider environmental justice concerns and to foreground the perspectives of Coast Salish peoples. Thank you to the reviewers for their feedback and perspective.

Before we explore what the future might hold for Washington state’s refining industry, we first must learn from the past. When were oil refineries first built in Washington? Why then? Why were they built where they were built? Through investigating these and other historical questions, we can better understand our present, and from there how we might influence the future of refining in Washington.

The coming decades will bring increasingly volatile oil markets as well as promising boosts in energy efficiency, vehicle electrification, and a shift to cheaper clean energy. As demand for oil drops, Puget Sound refinery communities can plan ahead for a smooth transition—protecting workers, local economies, and the environment to build a thriving and resilient future. This article is part of a special series on the issue.

The best place to start the history of oil refining in the Pacific Northwest is with the 1854 Treaty of Medicine Creek1 and the 1855 Treaty of Point Elliott.2 Both were a part of a series of treaties between Washington Territorial Governor Isaac Stevens, acting on behalf of the US federal government, and the Coast Salish peoples that have populated the region since time immemorial. Fishing rights were reserved to the Native American tribes under these Treaties, and fishing rights were and continue to be a major focus of these treaties. Probably no one in attendance at the signings was thinking about petroleum, though the first American oil refinery had just been built in Pittsburgh in 1853, and the first commercial scale oil wells would follow in a few years’ time.

The land ceded in the Treaty of Medicine Creek includes much of the south Puget Sound, including what is now Pierce, Thurston, Mason, and Kitsap counties. The smallest of the five Puget Sound refineries, the Par Pacific – US Oil refinery in Tacoma, was built much later on Puyallup land in what had once been thriving tidal flats laden with clams and oysters.

The other four, comprising over 90 percent of the region’s refining capacity, were built on Lummi and Swinomish land, tribes that were parties to the Treaty of Point Elliott, which covered the lands that are now King, Snohomish, Skagit, San Juan, Island, and Whatcom Counties.3 The two refineries in Anacortes are built on March Point, a finger of low-lying land in the estuary of Padilla Bay. Notably, the Swinomish Tribe disputes the US government interpretation of the treaty, claiming that March Point is designated as part of their reservation under the original terms of the Treaty. That claim was clarified as a matter of American law, if not of fairness or accuracy, by President Ulysses Grant in 1873 when he issued an executive order specifically demarcating the extent of the Swinomish reservation to exclude March Point.

Humble Beginnings

The federal government granted Washington statehood in 1889 and, in the early 1900’s, the largest industries in the new state were fishing and logging. But, as the newcomers exploited the region’s natural resources and as the broader economy grew and changed, the industries began a long decline. By the 1950’s, the focus of the economy had shifted away from harvesting natural resources. In Anacortes, timber mills and fisheries, which had been the backbone of the local economy for decades, were declining. Many local stores, without a prosperous industry to support economic activity, closed for good.

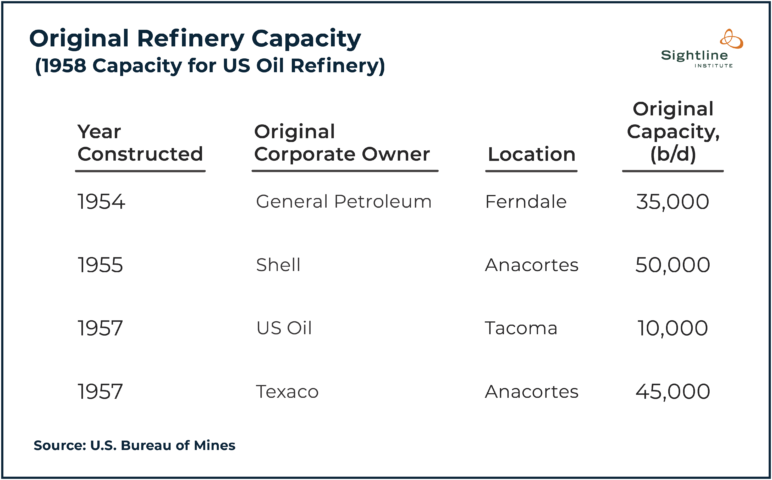

Local officials in Anacortes were looking for something, anything, to revitalize their town. That opportunity arrived in 1953 when the oil company Shell picked March Point as the site to build its newest oil refinery, to be completed by 1955. Shell’s Anacortes refinery was the second in the Puget Sound after the completion of General Petroleum’s (now owned by Phillips 66) refinery at Cherry Point near Ferndale in 1954.4 Cherry Point received its first crude delivery via ocean-going tanker on November 18, 1954.5

The excitement was palpable in both Anacortes and Ferndale. An advertisement in a July 1953 edition of the Seattle-Post Intelligencer promoted three taverns for sale in the Anacortes-Mt. Vernon area, noting that “a hundred million dollars in roads, bridges and huge oil refinery [sic] will be spent for the next 3 to 5 years. Think what this will mean for this area. Act at once.”6 A November 1954 Thanksgiving travel review in the paper noted that Ferndale was “experiencing a remarkable growth because of the construction of a new refinery.”7

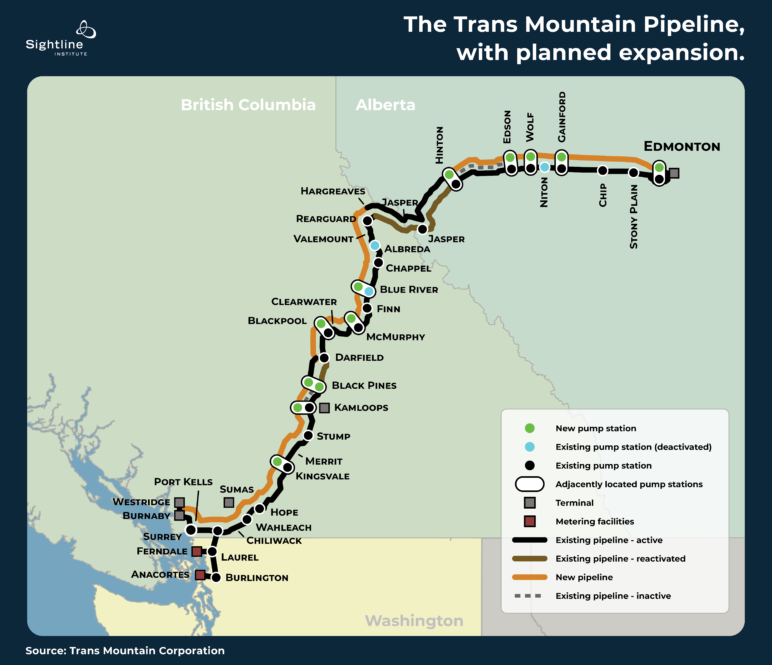

Shell’s project in Anacortes cost $75 million to construct, including building a 3,000-foot long pier designed to allow oil tankers to dock alongside. By November 1954, 1,200 employees were working on construction of the refinery8 with peak employment reaching 3,200 during May and June of 1955. On August 24, 1955, the site received its first “infusion” of oil from the Trans Mountain Pipeline of about 250,000 barrels of Canadian crude.9

Location, Location, Location

The oil industry is nothing if not economical: Puget Sound’s first two refineries were planned as a result of their proximity to the latest development in the industry—a discovery of oil and resulting boom in Alberta. As an industry executive put it in 1953, “Alberta oil fields are closer to the Pacific Northwest market than even California. The really persuasive consideration that led to the decision is the assurance of supply it gives us. It is becoming increasingly difficult to find new crude oil reserves in California.”10 Starting in 1950, California oil production could not keep up with demand and it started importing oil.11 12 By building refineries in Puget Sound, no longer would petroleum products need to be shipped from California up the coast, straining supply. Instead, crude could be shipped directly to Washington and refined there.

The industry moved to build infrastructure quickly after the discovery of oil near Leduc, Alberta in 1947. The Trans Mountain Pipeline was completed in 1953 to transport crude from Edmonton to Burnaby, outside Vancouver. The first Puget Sound refinery was completed in Ferndale the same year, just a few miles south of the Canadian border. To transport crude directly to the refinery, the Trans Mountain Pipeline Company constructed the 69-mile Puget Sound Pipeline Spur and started delivering crude to Ferndale in 1954.13 Pipeline work continued into 1955 to make crude deliveries to the new Anacortes refinery possible. The pipeline was finally finished when 630-feet of pipeline was laid under the Swinomish Channel to connect the new refinery to the Spur in Burlington.14 Alberta crude by pipeline represented a close, relatively cheap source of oil for the growing population in the Pacific Northwest. From a geographic and economic perspective, locating refineries in north Puget Sound made the most sense.

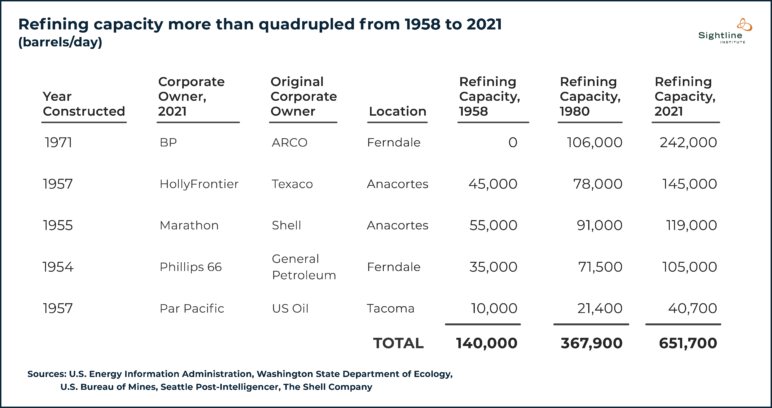

By 1958, four major refineries in Washington were operational: two in Anacortes (one owned by Shell, one by Texaco), one in Ferndale (owned by General Petroleum), and one in Tacoma (owned by US Oil).15 For context on the initial economic impact, the General Petroleum Ferndale refinery, with a capacity of 35,000 barrels per day, employed about 350 people year-round and had an annual payroll of $2 million.16 The Anacortes refineries had larger capacities upon first construction: Texaco’s capacity was 45,000 barrels per day and Shell’s was 50,000 barrels per day. The state’s total refining capacity in 1958 was around 140,000 barrels daily.17

While multiple small refineries would be constructed along Puget Sound shorelines between Tacoma and Bellingham in the decades that followed,20 only five refineries survived to the present day. At least three small refineries built prior to 1980 did not survive. First, the tiny United Independent Oil Co. refinery, built in 1977 in Tacoma, closed in March 1982 after operating for three years with a capacity of just 730 barrels per day.21 In December 1997, Sound Refining, located in the Tacoma Tideflats with a capacity of 11,900 barrels per day, also closed.22 Finally, Chevron’s refinery at Wells Point in Edmonds, originally built back in the 1950’s by Union Oil Co. with an original capacity of 4,000 barrels per day,23 shut its doors in 2000, having grown to a modest 6,200 barrels daily.24

Industry Expansion

The five refineries that made it not only survived, they grew to match the needs of the fast-growing populations of Oregon and Washington that were proving to be voracious consumers of oil. In fact, by 1960, residents of Oregon and Washington consumed about ten percent more petroleum per capita than the national average.25 And, from 1950 to 2000, the population of the two states more than doubled to reach 5.9 million in Washington and 3.4 million in Oregon. The nation’s love of the automobile was in full upward swing by the late 1950s, and more people meant more cars, and more cars meant more demand for oil.

The fifth and largest refinery built in Washington was the ARCO Cherry Point refinery in Ferndale, which has been owned and operated by BP since 2000. Built in anticipation of new crude supplies from the 1968 discovery of oil in Prudhoe Bay, on Alaska’s North Slope, the facility had an original capacity of 100,000 barrels per day.26 Studying the activity in the Arctic, industry executives correctly predicted that the Northwest would become a major refining hub due to the low cost of electricity (which powers many refinery operations) and easy access to deep water to handle large oil tankers. There were some obstacles, though.

Even then, Washington was known for its comparatively stringent pollution control standards, which the industry viewed as “major expenditures.”27 Plus, the local environmental community lobbied against tankers carrying Alaskan crude into the Puget Sound, arguing that a spill in the Rosario Passage en route to Ferndale would cause “inestimable damage” to the environment.28 The plan went through, however, and shipping lanes were soon marked for tankers to sail from Port Angeles to the new ARCO refinery at Cherry Point that was built for $200 million in 1971.29 30

It took almost 10 more years for Prudhoe Bay oil extraction to come online—and then it came in a flood. Alaska’s production increased from 173,000 barrels per day in 1976 to 1.2 million in 1978. Thanks to Puget Sound’s proximity, Washington’s refineries soon came to depend on Alaskan crude as their major source of feedstock. By 2003, fully 90 percent of the crude refined in the state was delivered by oil tankers from Alaska.31

In the early days, Alaska was producing so much oil that the industry proposed building a pipeline to move crude 1,500 miles from Port Angeles to Minnesota, with some of the oil stopping at a new refinery to be built near Moses Lake to provide products for eastern Washington.32 The plan was scrapped in 1982 after Republican Governor John Spellman rejected the proposal, arguing that building a pipeline in an earthquake-prone region would be a “very real threat to Puget Sound, which in my mind is a national treasure.” (It was the only time in state history that a governor has exercised the power of the office to unilaterally block an energy project until 2018, when Governor Inslee nixed a titanic oil train terminal proposed along the Columbia River in Vancouver, Washington.) Spellman’s move showed foresight, which became even clearer after the rapid decline of Alaskan crude production that followed its 1988 peak.

Another limitation to expansion took form in the 1977 Magnuson Amendment to the Marine Mammal Protection Act, which limited oil tanker traffic in Puget Sound by prohibiting federal permits that could increase that traffic. The law made an exception for permits that would increase the amount of oil meant for consumption in the State of Washington. The most immediate impact of the law was to thwart then-Gov. Dixy Lee Ray’s efforts to allow supertankers to deliver oil to Cherry Point. The law did not outlaw refinery capacity expansion, only expansions requiring federal permits that might increase tanker traffic.

And so the expansions continued. Easy access to the crush of Alaskan crude, combined with the increasing regional demand, meant it made economic sense for the Puget Sound refineries to keep increasing their capacity. By 1980, refining capacity at the five major refineries had more than doubled from 1958 levels to nearly 370,000 per day. Capacity has since doubled again, reaching 651,700 barrels in 2019.

Oil infrastructure both “upstream” and “downstream” of the refineries continued to expand, as well. Constructed from 1964 to 1965, the Olympic Pipeline was built as a joint venture between Shell, Texaco, and Socony, the operators of the three large refineries at the time. Prior to construction, refined products were transported by tanker or truck.33 The Olympic Pipeline now transports refined petroleum products to distribution stations along the Interstate-5 corridor all the way from Ferndale to Portland.

21st Century Fights Against Expansion

As Alaskan oil production declined, the industry adapted. As recently as 2003, Alaskan crude comprised 90 percent of all crude refined in Washington. By 2017, Alaskan crude accounted for just 35 percent of crude refined in Puget Sound refineries. About 34 percent of crude refined in Washington came from Alberta, Canada, and about 24 percent came from the Bakken fields of North Dakota, mostly by rail. The remaining 8 percent came from a variety of other places.34

Large scale delivery of oil by rail is a recent phenomenon in the Northwest. Since 2012, four of the five Puget Sound refineries have built facilities to accommodate massive trainloads of volatile oil from North Dakota. (The Shell refinery at Anacortes tried, but tribal and environmental advocates stalled the project.) Prior to those expansions, Northwest refineries could handle at most modest shipments of petroleum by rail. But the build-out of oil train unloading infrastructure allowed refineries to handle mile-long “unit trains” filled with crude oil—sharply increasing the state’s oil-by-rail capacity.

Refineries are not the only destination for oil trains on Puget Sound. In 2014, Targa Terminals in Tacoma expanded its capacity to unload rail cars. Now able to handle 36 rail cars at once, up from 24, the Targa facility can offload perhaps 40,000 barrels of crude per day delivered by train. Once offloaded, that crude travels up through the Salish Sea, adding to the problem of vessels transporting crude in fragile waters. Plus, terminals in Portland and Clatskanie, Oregon, draw even more oil trains through Cascadia, most of them traveling through Spokane and across eastern Washington.

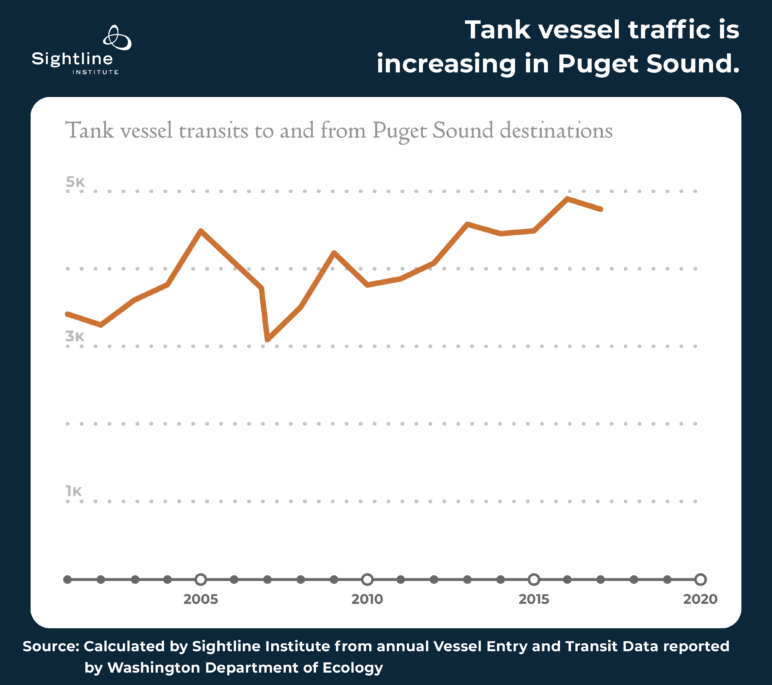

More oil-laden vessels are moving on the water, too. In fact, data from the past decade reveal rapid growth in oil and oil-product tankers sailing to and from Puget Sound destinations. Much of the increase can be attributed to a shift in the type of vessels favored by terminal operators. Big tanker ships are falling out of favor, making way for a growing fleet of smaller tank barges. The number of big tankers entering Puget Sound via the Strait of Juan de Fuca peaked prior to 2010, even as the industry added hundreds of tank barge transits. Overall, the number of tank vessel trips is clearly increasing over time, each one adding to the growing risk of a spill contaminating the waters and shorelines of the Salish Sea.

The increase in vessel traffic also interferes with the exercise of tribal fishing rights as guaranteed in the Treaties of Point Elliot and Medicine Creek.

No one knows what will happens next for the Northwest oil industry. If Oregon and Washington are successful in reducing their carbon emissions and associated consumption of petroleum products in accordance with their plans, the refineries will become unnecessary for Cascadia’s energy supply and therefore ripe for retirement. Yet, even if Cascadia does move beyond oil, there’s no guarantee they will shut down. It’s possible that they will simply continue operating, finding buyers of their products in other states or countries whose markets they may reach via tanker. If that happens, Washington would become a large carbon exporter, similar to British Columbia.

Which future will we choose? For the last seven decades, Puget Sound refineries moved overwhelmingly in one direction: more! More refining capacity, more oil-by-rail handling, more tanker traffic, more carbon pollution, and more risk of a devastating spill. It is time for a new direction.

In the next chapter, we lay out what a Puget Sound without refineries might look like in 2050.

This article benefited from past research by Ahren Stroming.