This article is part of the series Transitioning From Puget Sound Oil Refineries

Takeaways

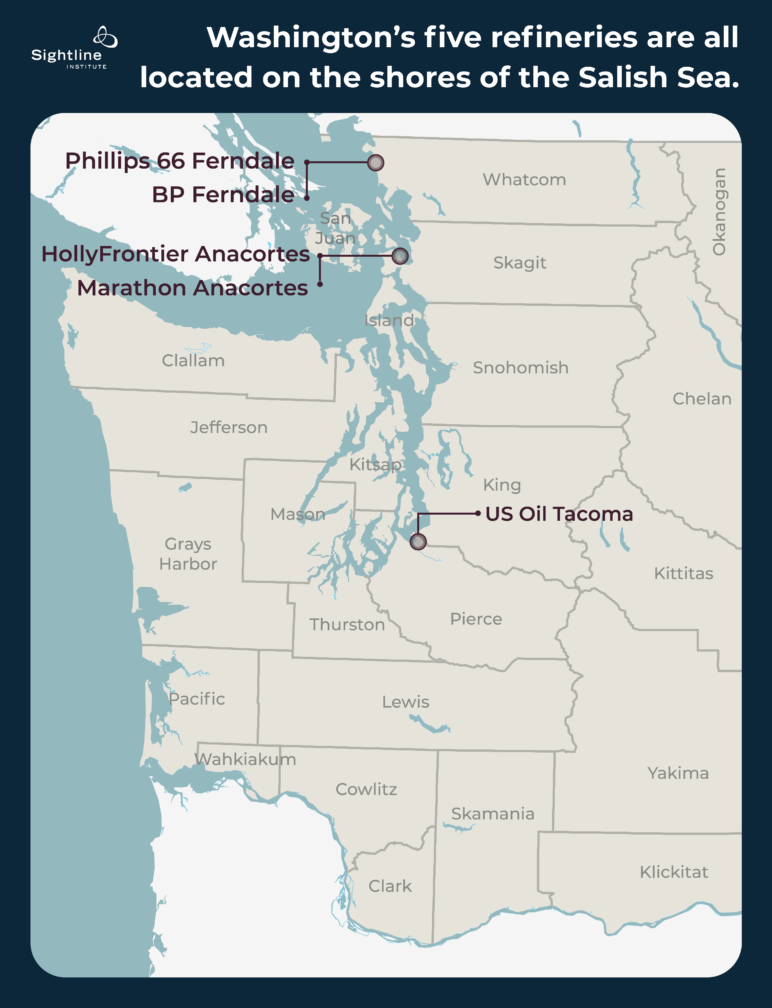

Washington’s five refineries are located in Ferndale, Anacortes, and Tacoma.

The refineries can process up to 240 million barrels of crude oil per year, more than the combined annual consumption of Washington and Oregon.

They refine crude oil into petroleum products like gasoline, jet fuel, and diesel, which account for half of total carbon emissions in Washington and Oregon.

90 percent of oil products consumed in Washington and Oregon is refined at the five refineries.

It is impossible to meet regional decarbonization goals without reducing petroleum consumption by at least 80 percent by 2050.

We know our role in solving the problem of climate change: Cascadia1 needs to slash its carbon emissions to near zero in less than three decades. Understanding how to do this is a bit harder, to say the least. Nowhere is that clearer than with the Northwest’s biggest contribution to climate change: the burning of oil products. Every year, residents in Oregon and Washington together burn an estimated 218 million barrels2 (9.2 billion gallons!) of gasoline, diesel, jet fuel, and other petroleum products. We burn this fuel mostly to power transportation—our cars, trucks, planes, boats, and trains.

The vast majority of that fuel is manufactured—converted from raw crude oil to useable consumer fuels—right here in refineries on the shores of the Salish Sea.

The coming decades will bring increasingly volatile oil markets as well as promising boosts in energy efficiency, vehicle electrification, and a shift to cheaper clean energy. As demand for oil drops, Puget Sound refinery communities can plan ahead for a smooth transition—protecting workers, local economies, and the environment to build a thriving and resilient future. This article is part of a special series on the issue.

What Do Refineries Do?

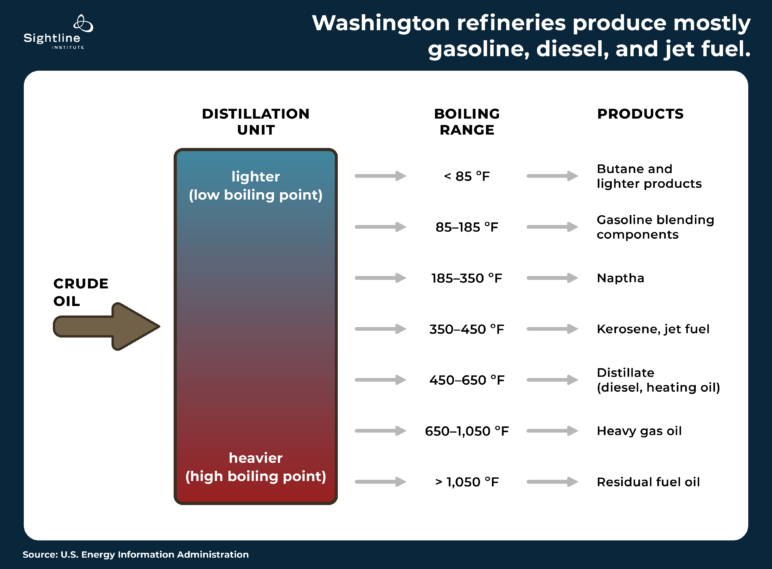

Crude oil is chemically complex. Refineries separate the crude oil into different products by heating it to certain boiling points. Lighter components boil into vapors at lower temperatures while the heaviest components need to reach temperatures greater than 1,000 degrees Fahrenheit to boil. After the components are separated, they are converted into usable products through cracking heavy molecules into lighter ones, or combining lighter molecules into heavier ones, depending on the product. Complex refineries, such as the five Puget Sound refineries, have multiple types of conversion units.3 Lastly, the products are treated to remove contaminants like sulfur and nitrogen before being sold to consumers. After all the separating, converting, and treating is complete, a 42-gallon barrel of crude oil will yield, on average, about 45 gallons of finished petroleum products. The increase in volume is due to finished products being less dense than crude oil. Nationally, gasoline accounts for 43.4% of refinery output, diesel accounts for 27.9%, and jet fuel accounts for 9.9%. Washington’s refineries have slightly different outputs: 45.8% gasoline, 17.5% diesel, and 13.5% jet fuel (2017 production).

Cascadia’s five oil refineries are strategically situated along the shores of Puget Sound and together process up to 240 million barrels of crude each year.4 These refineries are the mid-point of a sprawling web of supporting infrastructure, halfway between oil wells and the tailpipe of a climate-destroying chain of events: A trident-shaped oil pipeline delivers raw tar sands oil from Alberta. Combustible mile-long oil trains snake their way from North Dakota through the Columbia Gorge and downtown Seattle. Tanker trucks and “product” pipelines carry the finished fuels away for customers to use. And, a flotilla of tanker vessels and barges ferry crude oil and refined product around the Sound, south along the ocean coast, up the Columbia River, and across the Pacific.

All that bustling activity and infrastructure makes the Northwest economy run. In 2021, oil supports almost every facet of our transportation and delivery systems. Nearly every resident in the region depends on it daily.

How do refineries relate to Northwest carbon emissions goals?

The math of climate change is both clear and unforgiving: we must reduce emissions by at least 16 percent annually, starting now, to have even a 50 percent chance of limiting warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius.

Either we maintain the Northwest’s oil refining sector and fail to meet our climate goals, or we decarbonize by rapidly dismantling our oil infrastructure. That is what refinery retirement means: physically dismantling the oil refineries and their supporting infrastructure.

Fortunately, the centerpiece of this sprawling infrastructure—the refineries that provide the crucial link between supply and demand—are firmly under the influence of Cascadia’s people. Through our consumption choices and policy decisions, we control the fate of the oil refineries.

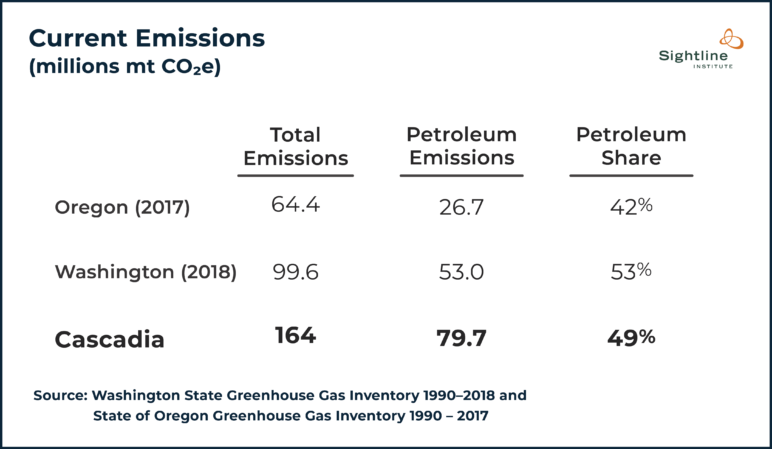

Refinery retirement would yield massive decarbonization benefits. The most recent available data also show that petroleum—that is, oil and its products—accounts for half of Cascadia’s greenhouse gas emissions. (See emissions data from Oregon and Washington.) Nearly all petroleum emissions come from transportation fuel. There is no other source of emissions as big as petroleum, and it’s not even close.

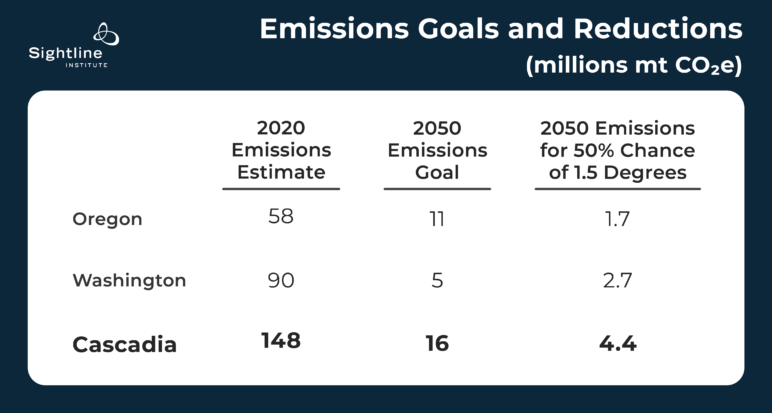

Factoring in declines in owing to the COVID economic contraction, Sightline estimates that the combined emissions of Oregon and Washington in 2020 stood at roughly 148 million metric tons of carbon-dioxide-equivalent (mt CO2e).5 Using the 2020 emissions estimate, Oregon emitted around 58 million mt CO2e, and Washington around 90 million mt CO2e. By December 2020, emissions in the United States had almost fully recovered to December 2019 levels, indicating that emissions in 2020 are likely more of a blip than the beginning of a downward trend. Emissions are expected to rise in 2021, although it is too early to know to what extent.

The Northwest does not plan to continue emitting carbon at 2020 levels, however. Governments in Cascadia have set ambitious carbon reduction goals through 2050. The Washington legislature updated its carbon emissions plan in 2020, setting a new goal of reducing emissions to 95 percent below 1990 levels by mid-century, settling at around 5 million mt CO2e. Oregon Governor Kate Brown signed an executive order in March 2020, setting reduction goals of 80 percent below 1990 levels by that time, which works out to around 11 million mt CO2e. If Cascadia meets those goals, the region would emit around 16 million mt CO2e annually from all sources by 2050.

And, as will be covered in great detail in subsequent chapters, there are abundant non-decarbonization reasons to shut down the Puget Sound refineries. Refineries pollute the surrounding air, water, and land. Pollution then poisons the people, flora, and fauna living on the land, drinking or swimming in the water, and breathing the air. Everyone living in the region is harmed, contributing to and exacerbating existing racial health disparities. The infrastructure is old and unsafe, both in the refineries themselves and their supporting infrastructure, such as pipelines and trains.

What might refinery retirement mean for the Northwest?

It is impossible to meet regional decarbonization goals without drastically reducing petroleum consumption and emissions. In 2018, petroleum alone accounted for 70.7 million mt CO2e. Even if Cascadia zeroed out emissions from all other sources—an extremely unlikely proposition—petroleum emissions would need to decline nearly 80 percent for the region to reach its 16 million mt CO2e 2050 target. Of course, in reality, petroleum likely will not be the sole source of greenhouse gases emitted in Cascadia in 2050, so to meet the decarbonization goals set out by the governments of Oregon and Washington, petroleum emissions must be reduced to less than 16 million mt CO2e.

If we meet these legislative targets, and assuming the only petroleum consumed in Cascadia was manufactured in Washington refineries, Washington refining capacity could decrease by 80 percent by 2050 and still be able to fully supply the needs of Oregon and Washington combined.

Unfortunately, these seemingly aggressive government goals are likely not enough. Sightline calculates Cascadia’s annual emissions should be less than 5 million mt CO2e by 2050 to maintain a mere 33 percent chance of limiting warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius, according to the global carbon budget determined by the IPCC. Realistically, petroleum emissions should be no more than 4 million mt CO2e by 2050 to save room for miscellaneous emissions from other sources like natural gas. That would be more than a 90 percent decline from the 70 million mt CO2e of petroleum emissions in 2018.

Many cross-sector and interconnected things need to happen nearly simultaneously for decarbonization, and refinery retirement, to happen. Washington’s Dept. of Commerce released an updated Energy Strategy in December 2020 detailing many of the necessary energy transition steps, including installing electric vehicle chargers across the state, electrifying buildings, and increasing renewable energy supply through modernizing the Western States electric grid.

In Washington, transportation means oil, and oil means transportation. In 2018, petroleum accounted for 43 million mt CO2e of the total 45 million mt CO2e from all transportation. The Energy Strategy denotes two broad strategies to reduce transportation emissions. First, by improving efficiency through improving vehicle fuel economies, reducing vehicle miles traveled, and increasing public transit options. Second, by incentivizing electric vehicles and mandating low carbon fuels.6

These strategies are good, but even if they are wildly successful in reducing petroleum consumption in line with decarbonization targets, the oil problem remains unsolved. If we are successful in cutting our petroleum consumption (and emissions) to a small fraction of what it is today, there is a good chance that the Puget Sound refineries would continue operating, simply accepting crude oil as they do now and shipping their carbon-laden products elsewhere. As it stands, Washington refineries export about 15 percent of their refined product to California, Alaska, British Columbia, and countries along the Pacific Rim.7

If Cascadia slashed its carbon pollution but maintained the oil refineries, refinery exports would mean the net effect on the climate might be close to zero. Yet if the region cuts it emissions while simultaneously retiring its refineries, it would send a shockwave through the oil industry, massively disrupting oil drilling in Alaska, Canada, and the western United States. Cascadia would be a trailblazer. Other states and countries around the world might be inspired to take similar action. Ultimately, the net effect on the global climate could well be magnified far out of proportion to the Northwest’s actual significance.

The solution to achieving our climate goals is simple: starting in our own backyard, reduce regional petroleum supply by retiring the refineries in accordance with reductions in regional demand for oil.

Our oil infrastructure is largely isolated from the rest of North America. Roughly 90 percent of the petroleum products consumed in Oregon and Washington are refined at the five Puget Sound refineries.8 9The remaining 10 percent is refined in the western United States and delivered via pipeline to eastern Oregon and eastern Washington. Although the Northwest does not produce any crude oil, it does have jurisdiction over nearly all the transportation, manufacture, and consumption of it.

That is good news: through this quirk of geography, Cascadia has an unusual ability to solve its climate problem.

In other words, it is well within our power to reduce our emissions, retire our oil refineries, and meet or exceed our most aggressive decarbonization goals.

Next in this series will be an exploration of the history of Cascadia’s oil infrastructure.