This article is part of the series Legalizing Inexpensive Housing

Update 9/16: Senate Bill 9 is now law.

Urban housing shortages aren’t just a cause of climate change. They’re a lot like climate change—it’s very hard to fix them unless you can get many different governments to act.

That’s what we told the New York Times this week when they asked for Sightline’s take on California’s proposed state-level legalization of duplexes and lot splits on most low-density residential lots.

Cities can and should lift their century-old bans on apartments, duplexes, cottages, and other lower-cost homes. But because there’s little material benefit unless many cities move at once, local politicians have little incentive to brave the political backlash, even when they know that allowing more housing is a good idea.

State governments don’t have that problem. They can face backlashes, sure enough—but when state legislatures act, as California’s State Assembly did Thursday, they have the power to meaningfully reduce a housing shortage.

As with Oregon’s similar bill from two years ago, lifting duplex bans statewide will not lead to a rapid transformation of California if it’s passed by the state Senate and signed by the governor. (A July study from the Terner Center for Housing puts the number of newly viable homes at about 700,000 in a state with 14 million homes.) But it will at least set the stage for gradual change. Under Senate Bill 9, when a residential structure in California reaches the end of its useful life, its owner would usually have the option to replace it with two, three, or four homes instead of just one bigger one.

That’s fantastic. It’s the sort of long-term payoff that most local governments would never get around to, any more than I will ever get around to reading Sometimes a Great Notion—even though I’m sure I’d be better for it if I did.

Here are a few other short Cascadian takes on this potential landmark victory in California.

1) As in Oregon, a bipartisan urban-rural alliance outvoted bipartisan opposition

After three years of trying, with editorial endorsements from the Los Angeles Times and San Francisco Chronicle, a bill sponsored by maybe the state’s most powerful legislator passed the state Assembly with 45 “yes” votes—in other words, with four votes to spare.

Whew.

Even more interestingly, on this high-profile issue in a deeply polarized state, seven of those “yes” votes for a Democratic-sponsored bill came from Republicans. (I’m including one independent who was a Republican until 2019.) Twenty-one of the opposing votes (which include both explicit “nos” and non-votes) came from Democrats.

It was very similar to the story in Oregon, the only other state in the nation to pass similar legislation so far. Two years ago, House Bill 2001 passed the Oregon senate with a single “yes” vote to spare. As I wrote in Sightline’s account of the Oregon process earlier this month, three of those “yes” votes came from Republicans. Its opposition, too, was bipartisan; four of the “no” votes came from Democrats.

It wasn’t quite this simple, but in Oregon, you could accurately describe this as an urban-rural coalition that outvoted opponents in the suburbs.

Thursday’s vote in California has echoes of that, too. The seven Republicans who voted for SB 9 represent the state’s nearly empty northwest corner, the area outside Modesto, parts of Bakersfield and its surroundings, the farmland north of Sacramento, the literal wilderness east of Fresno, the hills north of Burbank, and the desert around Yucca Valley. This looks like a political balancing act other states should be trying to replicate.

2) The lot splitting part might be a bigger deal than the duplex part

There are two main parts of California’s Senate Bill 9.

One is legalizing duplexes on almost all lots. (There are a few exceptions. Maybe the most interesting is that on lots that have been occupied by a tenant in the last three years, the law doesn’t allow any duplex that would require demolishing more than 25 percent of the exterior walls.)

The other main part of the bill is legalizing what it calls “urban lot splits.” This is a new process that would be possible only within city limits. If the owners indicate their intent to live on site for at least three years, they’d be allowed to split a lot into two lots, down to a minimum size of 1,200 square feet each. Each of those new lots would then be allowed to have a duplex.

The lot-splitting part is a bigger deal than it may seem. Other states would be wise to mimic the concept, ideally without the part where cities get to discriminate against renters for the first three years.

On many sites, lot splits can help solve one of the biggest problems with small-scale infill: how to get a construction loan. Many banks and credit unions struggle to figure out how to value a lot with an extra rental on site, and therefore can’t always offer good loan terms to people looking to build a backyard cottage or remodel into a duplex. But every lender knows exactly how to value a little lot with a new house on it. This would make mortgage financing easier, which would let more property owners with a bit less wealth take advantage of the law.

And another thing: Not everybody wants to be a tenant, just as not everybody wants to be a small-time landlord. Like Oregon’s Senate Bill 458, passed in May, the lot-split path in California’s SB 9 would create lower-cost homeownership options in new buildings as well as lower-cost rental options. This should significantly expand the number of people interested in taking advantage of the law and actually building homes.

3) This is good news for Cascadia, too

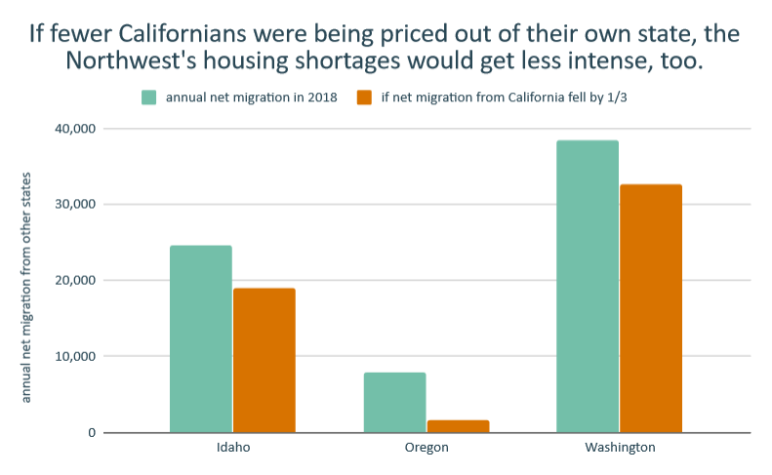

Year after year, as Sightline wrote last year, California sends a one-way jet stream of people moving north to Washington, Oregon, and Idaho. It’d be better for everyone if comparable numbers of people could flow in each direction.

This isn’t a matter of keeping Californians out; Californians should be as welcome in the Pacific Northwest as everybody else. But migration is richest when it’s a two-way street. If they could only afford it, thousands of Cascadians would move to California each year for jobs, family, or other opportunities. As the work of Jim Russell and others has shown, migration enriches both places, as well as the migrants themselves—when it’s allowed to happen.

4) a wave of even better local zoning reforms may follow

The other big California housing bill that passed the Assembly this week was Senate Bill 10. That law streamlines the environmental review process when cities do something that’s generally great for the environment: allowing small attached homes to exist. In the case of SB 10, it was up to ten per lot.

In other words, California didn’t just step in to help fix local problems; it also got out of the way of local reforms.

Here in Portland, we made a wonderful discovery in the wake of Oregon’s state reform: Once the status quo was no longer a legal option, Portland got over its hand-wringing and found a way do even better than the state required. Oregon legalized fourplexes with no affordability requirement. Portland did that, then added sixplexes with an affordability requirement, too.

San Diego, San Jose, Oakland, Sacramento, Berkeley, and other cities have already begun the process of re-legalizing “missing middle” housing. If California makes reform inevitable, progressive cities can stop debating the possibility of change and get down to maximizing the benefits of change.

5) There’s plenty more to do

Another big housing news event Thursday was much less pleasant. The U.S. Supreme Court struck down a national eviction moratorium ordered by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Among other things, that’s a reminder that there’s a lot more to fight for before everyone can be housed. We should be ending bans on all sorts of apartments, especially near jobs and transit. We should be giving people enough cash to pay basic rent; in the United States, extending the American Recovery Plan’s child tax credit into a permanent, universal child allowance would be a great place to start. We should end the costly parking mandates that prioritize storage for machines over homes for humans. As my colleague Nisma wrote in a piece published Thursday morning, we should use national, state, and local investments in community land trusts to help reinvent housing not as a pathway to private wealth but as a basic right.

Here’s the good news: if Oregon’s 2021 legislative session is any indication, a major victory can be a breakthrough that leads to more. Stay tuned—we’ll be publishing more on that soon.

Correction 8/30: An earlier version of this post, based on early reports, understated by one the number of Democratic “yes” votes for SB 9.