This article is part of the series Legalizing Inexpensive Housing

In 2019, Oregon passed a first-of-its-kind state law that ordered larger cities and the Portland metro area to rapidly legalize duplexes on all residential lots and fourplexes, triplexes, townhomes, and cottage clusters on more than half of lots. This is a short, reported history of how that law was passed in the face of fierce opposition. It was created in partnership with the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, its first publisher.

For 100 years, the battles for and against exclusionary zoning have been fought mainly at city halls. There’s a growing sense that they might be the wrong buildings for the job.

Housing shortages spill across city limits, after all, and no one city can single-handedly solve a regional shortage. So what’s in it for any particular city council to shoulder the political costs of trying to end the shortage? Like small countries trying to fight climate change without global solidarity, most city leaders considering joining the fight against a housing shortage will find the political calculus unappealing.

(For a series of smart analyses of this situation and how to fix it, see these articles by law professors Chris Elmendorf, David Schleicher and Roderick Hills, and Alejandro Camacho and Nicholas Marantz.)

State and provincial legislatures, however, are different. Unlike city councils, they have the power to actually solve the problem.

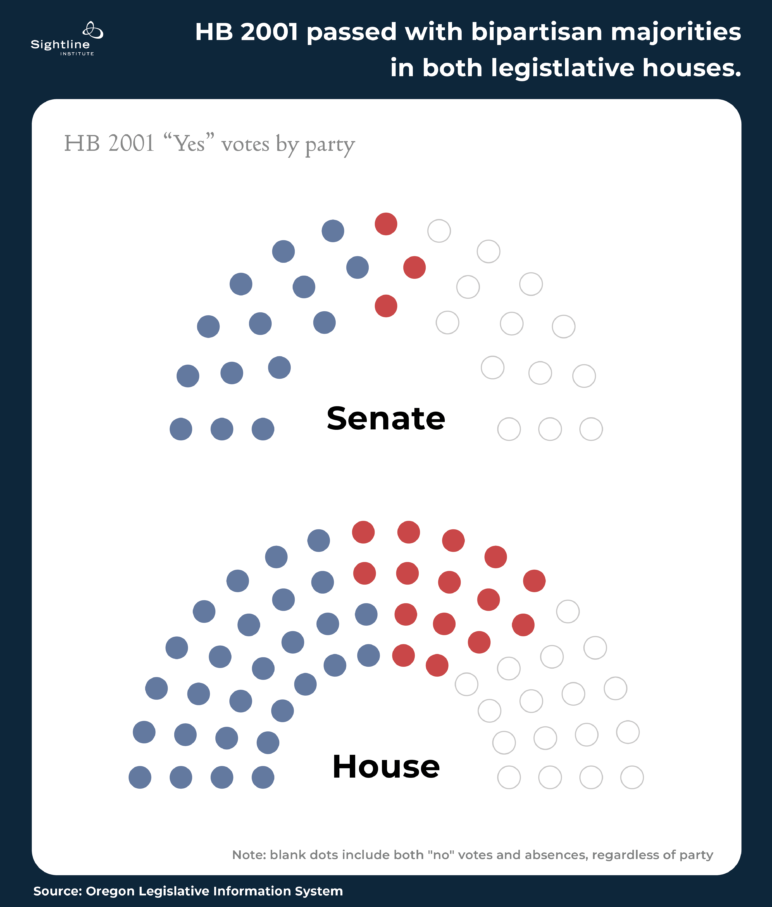

In 2019, Oregon proved that it’s possible for state legislatures to take groundbreaking action against local bans on lower-cost housing types. House Bill 2001, championed by Democratic leaders but passed with bipartisan majorities, made Oregon the first U.S. state to ban single-detached zoning at the state level.

The law legalized—or, to be historically accurate, re-legalized—duplexes on every residential lot in jurisdictions representing 68 percent of the state’s population. It also:

- Voided contractual bans in future homeowner covenants on what it called “middle housing”: backyard cottages, townhouses, and 2-4 unit buildings.

- Struck down the two most disruptive local restrictions on accessory dwellings: that they include their own off-street parking spaces and that they are illegal on renter-occupied properties

- Struck down local rules putting “unreasonable cost or delay” on development of so-called “middle housing.” Subsequent state rulemaking interpreted this to ban local mandates of non-standard lot sizes or more than one parking space per home.

In 36 of those jurisdictions, the law went further. Twenty-four cities and counties in the Portland metropolitan area and 12 cities with populations above 25,000 were ordered to legalize triplexes, fourplexes, attached small-lot townhouses, and cottage clusters in “all areas.” Subsequent rulemaking interpreted this to generally mean that triplexes must be allowed on at least 80 percent of parcels, fourplexes, and cottage clusters on at least 70 percent, and townhouses on at least 60 percent.

State rulemaking for all the jurisdictions also set tighter limits on parking mandates based on lot size, making HB 2001 the largest state-level parking reform law in U.S. history. For example, a fourplex on a 5,000 square foot lot in one of the 36 more urban jurisdictions can’t be required to have more than two parking spaces, total. (The state doesn’t restrict the lot owner’s ability to add more than two spaces, but it’s up to the lot owner.) Any larger mandate, the rulemaking concluded, would constitute an “unreasonable cost.”

Oregon’s law, the first of its kind in U.S. history, made national headlines and was immediately imitated elsewhere. Within two years, lawmakers had introduced bills with similar provisions in Connecticut, Minnesota, Maryland, Montana, Nebraska, New Hampshire, North Carolina, Vermont, Virginia, and Washington. (In California, a similar bill was re-introduced twice.) British Columbians, too, began talking about the possibility of a provincial bill.

But by summer 2021, nothing nearly so sweeping had yet passed anywhere else.

Why not? What had worked in Oregon that didn’t seem to be working elsewhere?

A bipartisan achievement

The support was bipartisan; the opposition was bipartisan.

This report will describe many factors that combined in Oregon to lead to the bill’s passage. But maybe the fundamental thing for people outside Oregon to understand about the bill was that it was bipartisan from start to finish.

The support was bipartisan; the opposition was bipartisan. And even in a state with Democratic supermajorities, this bill that was a top legislative priority of the Democratic house speaker would have failed in both houses without Republican votes. Even then, it passed the state senate with a single vote to spare.

This makes House Bill 2001 unusual not only as housing legislation, but as legislation in general in one of the most polarized states in a polarized country.

In 2019, the year of the bill’s passage, Oregon’s legislature shut down for 12 days after most Republican senators fled the state in two quasi-legal “walkouts.” Their goal was to prevent the senate from reaching quorum for passage of a business tax hike and a proposed cap-and-trade carbon pricing bill.

Three years after a squad of armed far-right extremists had seized a federal building in Oregon, rhetoric was hot. Republican State Sen. Brian Boquist told a video reporter that if state troopers were to use their constitutional authority to compel him to attend, the law enforcement agency should “send bachelors and come heavily armed.”

And yet, on the last day of the scheduled legislative session—with the cap-and-trade bill dead and everyone furious at everyone else—Republicans returned to the capitol to allow passage of a flurry of bills, including HB 2001.

What had led Democrats, who seemed to command total power in Oregon, to design a bill that would win votes across the aisle? And what led Republicans to cross party lines and give the hated leader of the majority party the passage of her top housing priority?

Here are eight answers to those questions.

Ingredient 1: A tradition of state-led land use planning

The hardest factor for most other states to replicate is Oregon’s tradition of state oversight of local zoning.

Direct state regulation of local zoning began in a 1973 anti-sprawl law pushed through by the state’s wildly popular environmentalist Republican Gov. Tom McCall and a Eugene-area dairy farmer turned Republican state senator, Hector Macpherson. But with the 1970s realignment of the western states’ Republican Party to focus heavily on property rights, Oregon’s anti-sprawl law and the “urban growth boundary” it created became closely associated with the state’s Democratic Party instead. Republicans built close ties to the urban growth boundary’s foes: Oregon Home Builders Association, the Oregon Association of Realtors, and the Oregon Property Owners Association.

The allegiance of Oregon’s Democratic Party to anti-sprawl laws had an interesting side effect: to the extent that the state ran short of housing, Democrats would be blamed for it.

Looking to prevent that scenario, housing advocates, urbanists, and environmentalists of the 1970s and 1980s also wrestled pro-infill policies into the administrative interpretations of McCall’s and Macpherson’s landmark anti-sprawl law. To interpret and enforce the law they built two institutions, the state Department of Land Conservation and Development (DLCD) and a non-governmental organization, 1000 Friends of Oregon.

Between 1978 and 1982, DLCD mandates and the threat of non-compliance lawsuits from 1000 Friends led cities within the Portland metro area to double their zoned capacity.

But many of those “upzones” ended up in neighborhoods with less political power of their own: poor ones, industrial zones, and the small scrap of Portland that was then majority Black. The state’s richer and whiter areas, the ones most likely to actually add homes if adding more homes were legal, saw less change over the decades. Some such neighborhoods were even downzoned.

“Oregonians hate two things: They hate density and they hate sprawl,” says Jon Chandler, a former lobbyist for the Home Builders Association. “Everybody thinks that somebody else should live in an apartment.”

Ingredient 2: A powerful, committed leader

From Chandler’s perspective, Oregon’s Democratic Party maintained “years of basically polite fictions that you didn’t have to move the urban growth boundary much, you just had to densify. Which is, factually, completely accurate. The only problem was that it was never going to happen.”

But the party’s urgency for infill dialed up after Rep. Tina Kotek took over as speaker of the Oregon House of Representatives in 2013.

Kotek, a native of central Pennsylvania, had moved to Portland in 1998 after a graduate degree in Seattle. Her first home out of grad school had been in a fourplex tucked into one of Portland’s older and wealthier neighborhoods. She then worked in social services before her 2006 election to the legislature as a Democrat, becoming one of its first openly lesbian members.

By 2016, the working-class neighborhood where Kotek owned a home was gentrifying rapidly. That was also the peak of Portland’s post-recession rental crisis, which saw the city’s median monthly rent rise by about 10 percent in one year—and in older buildings, even faster.

“The people she knows locally and her sort of trusted community advisors were raising alarm bells,” says Taylor Smiley Wolfe, Kotek’s top housing policy aide from 2016 to 2019. “Her district was the epicenter of the displacement crisis, so her constituents were raising alarm bells.”

Kotek had recruited Smiley Wolfe from California after she wrote a master’s thesis that argued for California to allow tighter and broader rent controls. By that point, the house speaker had big things in mind. Kotek wanted Oregon to lift its ban on regulating rents. And she wanted it to simultaneously force cities to lift their bans on attached homes—in other words, to end single-family zoning.

“We did not have enough housing, particularly for those of moderate and low income, in virtually every city across the state,” says Mary Kyle McCurdy, deputy director of 1000 Friends of Oregon. “There were constant stories, analyses that we did not have enough housing and it’s taking too long to develop it, and we’re not allowing enough variety of housing types.”

Unlike many of her legislative peers, Kotek had never served in local government and perhaps had less sympathy for local opposition to addressing what she saw as maybe the state’s largest problem. She called a meeting in 2016. Invited were Chandler, McCurdy, and lobbyists for the state’s cities and counties.

“It was a ‘come to Jesus’ meeting with the cities,” says Chandler. “Here’s what’s going to happen and you’re going to hate it.“

“She said, we’re going to start doing things differently here about allowing more diverse housing inside of cities,” McCurdy recalls. “It’s not going to be business as usual. … You’re not doing what you need to be doing, and we’re in a housing crisis.”

Most cities and county officials saw things differently. From each jurisdiction’s perspective, it was making progress in its own carefully crafted and negotiated way. But from Kotek’s perspective, the state as a whole had clearly been failing.

“She knew this was a statewide issue,” says McCurdy.

“I think one of the fundamental things that Tina brought to the table was a willingness to look at the math, not at the ideology,” says Chandler. “Before that, people would cover their ears and hum loudly. Tina didn’t do that. She’d say, yep that sucks.”

Ingredient 3: A pre-existing foundation of policy research

With a few exceptions for the leaders of each house, Oregon’s legislature is part time and lightly staffed. Its factfinding process, therefore, can be thin and reliant on lobbyists and other interest groups.

So it helped the state that several Oregon cities, including its largest, had already spent years researching the possible legalization of “middle housing.”

Portland’s snail’s-pace progress on its so-called “Residential Infill Project” (see our separate history of Portland’s zoning reform) was one of the factors that had moved Kotek to pursue state action. But during its years of deliberation, Portland had in fact gathered the building blocks of a strong argument for zoning reform.

- It won’t be too dramatic: Many people assume that legalizing any type of “middle housing” will lead to rapid demolition. But Portland, which had legalized duplexes on corner lots in 1991, had already calculated that 28 years later, only 3.5 percent of its corner lots had duplexes on them. Kotek’s office made this one of their primary talking points.

- It won’t be insignificant: Other people are dubious that legalizing small-scale housing options could have a significant impact on housing supply. But in late 2018, an economic study contracted by Portland estimated that the city’s proposed fourplex legalization would increase the average homebuilding rate by about 20 percent, satisfying 13 to 15 percent of the entire region’s projected homebuilding demand over the next 20 years. A state economist who was aware that HB 2001 was about to be introduced cited that finding in a December 2018 blog post circulated to legislators.

- Much local control will remain: While the state law was ambiguous about what new buildings could look like and what anti-displacement measures could accompany them, years of debate over those questions in three cities—Portland, Bend, and Tigard—offered reassuring examples that cities would retain significant control of low-density zoning. Like in those cities, Oregon jurisdictions would continue to regulate the size and height of new buildings. They just wouldn’t be able to prevent buildings from having more than one home inside.

Ingredient 4: A trial run two years before

House Bill 2001 had a predecessor. That bill, HB 2007, was introduced in 2017 by Kotek and would have legalized duplexes on most urban lots in the state.

Like many new legislative ideas, HB 2007 failed, but in ways that paved the way for HB 2001:

- It convened supporters. Sprawl regulators like McCurdy and homebuilding advocates like Chandler rarely found themselves on the same side of legislation. HB 2007 showed they could be.

- It smoked out opponents. HB 2007 was killed after being assigned to a state subcommittee that seemed to be its best fit, but was chaired by Sen. Kathleen Taylor, a Democrat representing several low-density areas of inner southeast Portland and its southern suburbs. Taylor hated the bill and persuaded her colleagues on the subcommittee to block it. Two years later, Taylor was still, quietly, the bill’s primary opponent. But Kotek quietly routed the bill to a different subcommittee.

- It located sticking points. HB 2007 became a lightning rod mostly over a different provision: a weakening of some demolition protections for future historic districts, including the one in which Taylor (and McCurdy) personally lived. In 2019 this proposed reform was carved into a separate bill, which also failed to pass.

One oddity of the transformation of HB 2007 into HB 2001 was that, by legalizing fourplexes, the second bill exceeded the ambition of its unsuccessful predecessor. Even the bill’s authors found this to be a surprise.

Smiley Wolfe says she had assumed, in light of the earlier duplex bill’s failure, that four homes would be a starting point for negotiation: “If you tell people that there could be quadplexes instead, they’ll be more likely to think that duplexes are not such a big deal.”

But the fourplex discussion in 2019 turned up two unexpected dynamics.

- More units can mean less expensive homes. Because land costs could be split four ways rather than just two, HB 2001 supporters could plausibly claim that new homes created by the bill could be immediately affordable to middle-income Oregonians. In some cases, new fourplex homes could even be economically viable at lower prices than the old homes they might replace. Duplex legalization couldn’t promise this.

- Opposition to the bill was qualitative, not quantitative. Most opponents didn’t want to settle for duplex legalization. They insisted on the status quo, and thus didn’t offer wavering lawmakers an attractive compromise. “I don’t remember any neighborhood associations or local governments saying the problem is that the number of units is too great,” says Smiley Wolfe. “Which I was really expecting, frankly.”

Ingredient 5: A time-intensive coalition

By 2019, 1000 Friends of Oregon had spent three years investing in Portland for Everyone, a locally specific pro-housing campaign. (See our separate case study for a detailed narrative.) That campaign’s founding organizer, Madeline Kovacs, led a team of volunteers that met 3,000 Portlanders face to face and convened a broad network of local institutions in favor of zoning reform.

Before and during the bill’s passage, Kovacs and her colleague Michael Andersen (Portland for Everyone’s former contract writer and the author of this case study) joined Sightline, a regional sustainability think tank. From there, both continued to work alongside 1000 Friends and others to pass HB 2001.

The result was a wide array of institutions signing off on the bill, including the Community Alliance of Tenants, OPAL Environmental Justice Oregon, Portland Public Schools, Business for a Better Portland, Sunrise PDX, and AARP.

Supporters of the proposed Portland reform, knowing that the faster-moving state reform was likely to ensure passage of the local one, organized phone banks using the Portland for Everyone supporter list. Henry Kraemer, a volunteer who had previously worked as an organizer and lobbyist for a youth-voting-rights nonprofit, opened his own contact list to help swing votes in Portland’s delegation.

Among the most politically important supporters were affordable housing developers. When the bill reached the Ways and Means committee, its opponent Sen. Taylor introduced an amendment that would have gutted the bill by legalizing 2-4 unit infill only if the homes met particular price targets.

With the legislature racing to pass bills before a possible Republican walkout, the amendment might have been a tempting way to defuse a vote that was scrambling their constituents’ allegiances. But backers were able to quickly mobilize affordable housing developers, who would seem to be the main beneficiaries of Taylor’s amendment, to oppose it in private communication with legislators. Taylor’s amendment was shot down before it ever received news-media attention.

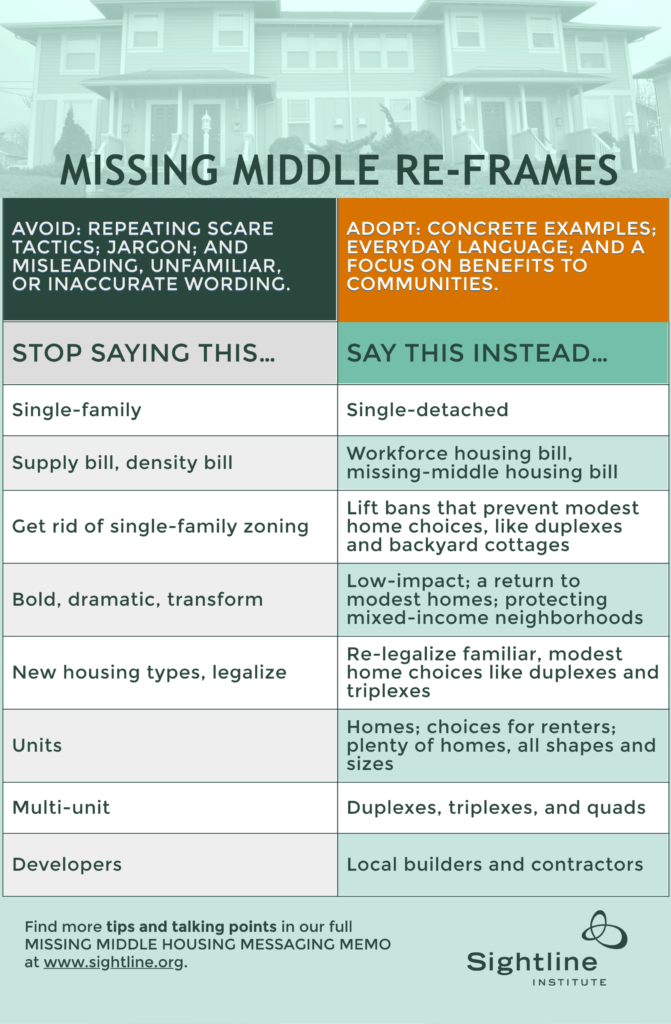

Ingredient 6: A road-tested messaging strategy

Another benefit of the Portland for Everyone campaign was that Kovacs, Andersen, and their collaborators had just spent several years conducting real-time tests of the best ways to talk about getting rid of single-family zoning.

One of their conclusions: never use the phrase “single-family zoning.”

Or, if you can help it, the word “zoning.”

For an issue that was unfamiliar to many legislators and cut across existing ideological lines, good framing for the issue was crucial. The week the bill went public, Sightline privately circulated a memo to potential supporters urging them to focus on what the state had to gain—legalizing “middle housing,” a phrase that evoked both moderation and the middle class that these housing types can serve—rather than on the type of zoning that the state would allegedly lose.

The advice was informed by a previous focus group in Seattle and by studying political language there and in Minneapolis and California. Several passages:

Emphasize Missing Middle Homes: This is a “missing middle” housing bill that would re-legalize a variety of home choices in the state’s job centers, like duplexes, triplexes, and quads, rather than reserving close-in neighborhoods for only the biggest and most expensive housing.

Center messages around the people who need middle-class, workforce homes: This is a workforce housing solution, helping keep cities across Oregon affordable for moderate-income, working families and small households like seniors or young couples. …

Middle-class homes, not McMansions: When we allow a variety of modest home types and allow more than one home on a single lot, we can also help reverse the trend toward bigger and bigger—and pricier—“McMansions” in cities across the state. …

Focus on seniors and young people: For many young people aspiring to homeownership, a “starter home” is out of reach. Since 1970, average sizes for new detached houses have soared by 64 percent. That’s a huge driver of rising home costs. Re-opening middle homes as an option would let many young Oregonians start building their American dreams, and let many older Oregonians savor their own. …

Show, don’t tell—use photos: When mental images are absent, exaggeration and fear can rush in. But duplexes, triplexes, and quads are more inviting when people see what they look like. In fact, in most neighborhoods these home types are quite familiar. (Find public-domain missing middle photos in Sightline’s online image library.)

The memo also included a list of language suggestions:

Ingredient 7: A seemingly united Democratic front

In California, criticisms of state-led zoning reform have come from both the ideological left and center of the state Democratic Party. As in Oregon, some California centrists and conservatives organized around a principle of “local control.” Some on California’s left wing, meanwhile, have argued that new market-rate housing would disrupt and gentrify poor neighborhoods in ways that existing market-rate housing does not. Oregon’s HB 2001, though, saw no significant defections from the party’s left wing.

Contributing to a sense of a unified, cross-ideological front was the bill’s first committee hearing. To endorse the bill, Kotek and Smiley Wolfe recruited:

- Mike Wilkerson, an economist who had just been the lead author of a report titled “Housing Underproduction in Oregon,” financed by the national coalition Up for Growth, to make the case that Oregon faced a shortage.

- Marisa Zapata, a planning professor at Portland State University, to run through the origins of U.S. zoning in class and racial exclusion.

- Deborah Kafoury, chair of the commission of Oregon’s largest county, a former House minority leader, and the daughter of two prominent liberal Portland politicians, to discuss the role of zoning reform in fighting segregation.

Another crucial bit of context: Kotek had also been a lead author (and Smiley Wolfe the policy lead) on SB 608, another groundbreaking bill passed at the start of the 2019 legislative session. As part of a broad tightening of eviction rules, it made Oregon the first U.S. state to directly regulate the price of rental housing. Though Smiley Wolfe says there was no explicit agreement that the bills should both pass, Kotek’s passage of this major goal of tenant organizers gave her the credibility to advance an accompanying supply bill without meaningful complaints from tenant groups that it did too little for below-market housing.

HB 2001 did have staunch opponents in the Democratic Party, mainly from representatives of some suburban districts. But those opponents kept publicly quiet throughout the process despite ultimately voting “no.” They had little incentive to hold a public argument with their party’s legislative leaders.

“If tenant organizations had opposed the bill, I think that could have been the thing that they needed to hide behind to be ‘good progressives’ even though they wanted to oppose it regardless,” Smiley Wolfe says. “That would have been a convenient opportunity for them.”

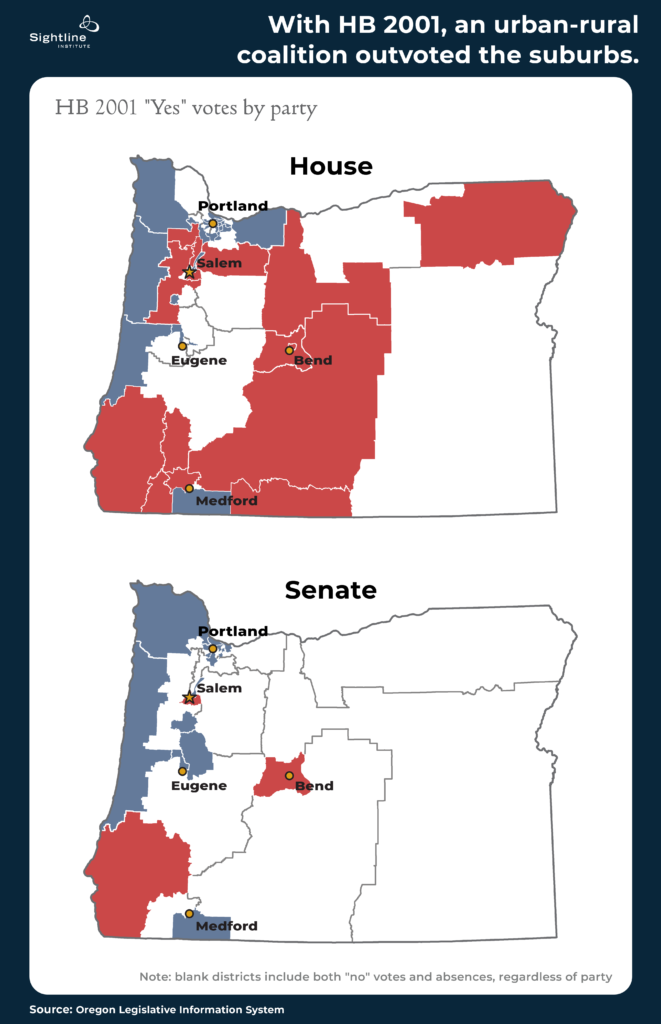

Ingredient 8: A solid base of Republican support

The final ingredient of HB 2001’s passage may have been the most fundamental: bipartisan support. Without it, the bill would not have passed.

Voting decisions on the bill were somewhat idiosyncratic and complicated by the Senate shutdown. But one way to understand them is as an alliance of Oregon’s urban and rural areas against the suburbs.

So, what brought Republicans on board?

One set of prospects were the handful of Republicans from more urban districts. One was Rep. Cheri Helt, the lone centrist in the Republican House caucus at the time. Helt represented a fast-growing Democratic-leaning district in and around the City of Bend, in arid central Oregon, for one term. (In 2020 she would become the only supporter of HB 2001 to lose a re-election bid, something Helt attributes entirely to sharing a party label with Donald Trump in her district.)

Helt, a restaurant owner and the daughter of a Michigan homebuilder, also happened to live in an old house in the midst of a recently constructed subdivision that included many duplexes, triplexes, and quads as well as a new park and several commercial hubs.

“I have this really unique perspective, in that I have watched it all around me, and I am not afraid of it,” Helt says. “If you listen to people, they’ll say those quads, those apartments, they’ll lower our values. But it’s the exact opposite in my neighborhood. … People are like government housing is coming in, and I’m like, It doesn’t have anything to do with government housing!“

Joining Helt in support was her district neighbor Rep. Jack Zika, another freshman Republican and relative moderate. Zika, a Realtor, sat on the planning commission of the City of Redmond, outside Bend. Helt, Zika, and other early Republican backers extracted a handful of concessions from Kotek:

- Specifically in the case of existing homeowner associations, the bill wouldn’t attempt to void past contractual agreements. Only future restrictive covenants would be struck down.

- The bill would include townhouses—essentially including the right to subdivide a lot—as an “ownership friendly” middle housing option alongside the rental-oriented plexes.

- The bill would add language preventing cities from assuming massive but imaginary future infill as a way to further slow expansions of their urban growth boundaries.

The second and third bullet points were also insisted on by the other Republican-aligned institutions: the state associations of Realtors, homebuilders and property owners.

Few Oregon homebuilders worked on small-scale infill housing. Chandler, their former lobbyist, said he had signed off on Kotek’s middle-housing concept anyway, assuming it would never pass. But on the off-chance that it did pass, he figured, it would undermine liberal Portland homeowners’ support for the urban growth boundary that had made infill economically necessary.

“I told my clients, We have been trying to do this on the merits and we have gotten goddamn nowhere,” Chandler recalls. “Let’s jiu-jitsu this thing.“

As for the policy argument, many sources agreed that Republicans are more likely than Democrats to believe that in a growing state, increasing the housing supply holds down home prices.

“Frankly, they understood the policy arguments we were making and they didn’t disagree with us,” says Chandler.

Two people familiar with legislative conversations said not to underestimate the appeal, to some rural Republicans, of passing laws that would annoy some well-off Portlanders.

“They didn’t want to give Tina a win,” says Chandler. “What they liked was the pieces that slapped the cities around.”

Asked about that, former Rep. Helt laughs and says she tries to maintain a more idealistic perspective about why more of her colleagues didn’t withhold their votes in order to prevent the state’s Democratic leadership from finding a possible path out of the state’s housing shortage.

“We are in a housing crisis; look at our homeless numbers,” she says. “You always try to get 60 percent of what you wanted, and if you get 60 percent, you win. If you fight for 100 percent of what you want, you get zero and everybody loses. I learned that on the school board years ago.”

Things are different when you’re in the majority, Helt concedes.

“If the speaker had the votes in her own caucus, she wouldn’t have done anything,” she says. “Really, we’re the best people and the best government we can be when we really need each other to get stuff done.”

Coming next: An overview of follow-up housing bills in Oregon’s 2021 legislative session, suggesting that the fight over HB 2001 may have led to a breakthrough on state-led zoning reforms.